Introduction

Public health and public education are likely the two most under-resourced public services in urban communities. Interestingly enough, these services are also the most likely to change the life trajectories of poor and working poor families. Public policymakers are constantly faced with the problem of ameliorating the symptoms of poverty that impact both public education and health.

The Problem

Underutilization of Health Care

According to the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, in 2010, 1001 per 100,000 children were hospitalized for asthma. Among the top U.S. cities, Philadelphia had the lowest rate of children who had received immunizations. And sadly, among the top U.S. cities, Philadelphia had the highest child mortality rate.1

“In 2006, 87.9% of children aged 4 to 17 were examined or treated by a dentist in the past year. However, 12.1% or about 88,700 children in Southeastern Pennsylvania did not receive a dental exam. When asked why the child had not seen a dentist in the past year, approximately one out of five (22.9%) responded that the child did not need a dental exam” (Public Health Management Corporation Community Health Data Base [PHMC CHDB], 2007). There could be numerous reasons for the aforementioned responses, including that the parents of young children were ashamed or embarrassed or may not have been well informed about dental healthcare.

Adolescents in southeastern Pennsylvania are even more removed from dental healthcare. According to a 2006 report from PHMC, “Older children aged 15–17 years (86.5%) were least likely to have received a dental exam” (PHMC CHDB, 2007).

In general, children in Philadelphia are not receiving proper healthcare. In spite of this, only 6% of Philadelphia children are uninsured, so primary care and preventive health is a matter of healthcare utilization rather than lack of access to healthcare resources. It seems that in poor communities, families are not consuming the available preventive healthcare services for a multitude of reasons, including lack of awareness, misconceptions about healthcare and difficulty accessing services.

Underutilization of preventive healthcare is a national problem. But why don’t people who have access to affordable and even free healthcare services consume these the services? Low socioeconomic status is known to influence insufficient health care utilization. “In 2011, the last year for which numbers were available, Philadelphia had about 56,000 more people living in poverty than it did in 2004, a far greater rate of increase than for the population as a whole. In 2012, it had about 172,000 more people eligible for food stamps than it did eight years earlier; three out of every ten city residents are now food-stamp eligible.” Moreover, those of low socioeconomic status are disproportionately more likely to experience poor health outcomes compared with those of median socioeconomic status.

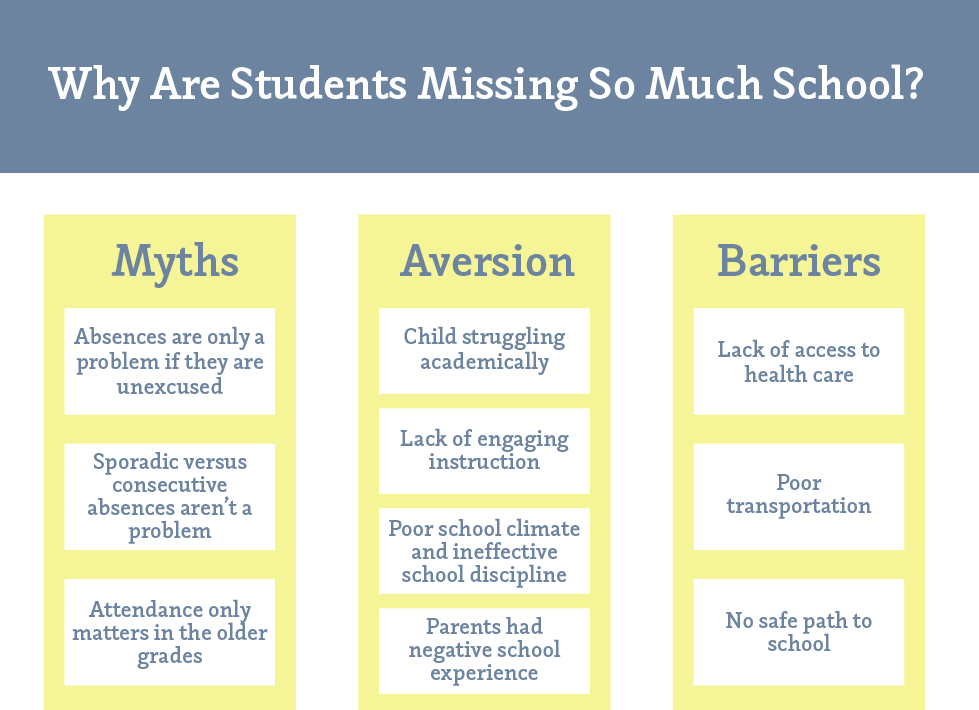

Chronic School Absences

In order to address the income and racial achievement gaps and disparities in standardized test scores and graduation and dropout rates, we must see chronic absenteeism as a key indicator of student success. “Research indicates that chronic absenteeism often leads to students dropping out. Average attendance below 90 percent—missing 18 days or more out of the school year—often translates into 3rd graders reading below grade level, 6th graders failing courses, and 9th graders leaving school altogether. Chronic absenteeism rates run as high as one-third of students in low-income, urban school districts, and the effect of absenteeism can be even more severe for students from low-income families.” Chronic student absenteeism belies additional challenges in a student’s life.

Courtesy of the Philadelphia Public School Notebook

Chronic Asthma

Chronic asthma is one of the leading causes of absenteeism in urban low-income communities. Asthma is connected with absenteeism because many children are undiagnosed or they do not receive appropriate medical treatment. Children may miss multiple days of school due to unnecessary emergency room visits for asthma-related symptoms including wheezing and coughing. “Children living in urban minority communities usually have higher rates of asthma in severe forms for several reasons, including limited access to health care and poor disease management” (The Baltimore Student Attendance Campaign and Elev8 Baltimore, 2012).

“In addition, asthma also decreases a student’s cognition, connectedness with and engagement in school and thus decreases student motivation to attend and succeed in school, consequently lowering the chances of educational attainment. Studies show a correlation between asthma status and absenteeism, and that absenteeism increases with worsening severity (Moonie, 2006; Moonie, 2008; The Baltimore Student Attendance Campaign and Elev8 Baltimore. (2012).” Interestingly, many cases of asthma exacerbation can be prevented with education regarding the disease processes and the preventive measures individuals can take to protect their children from an attack. For example, smoking makes asthma worse; removing an asthmatic from an environment where there’s a smoker may be all the treatment the asthmatic needs.

No School Nurses

Philadelphia is experiencing a public education crisis. Presently, SDP is facing an unprecedented structural deficit. Families are having to make hard choices about whether to keep their children in their cash-starved public schools for another year or seek other options such as public charter schools, private and parochial schools or even leaving the city. For a family with the resources to make these choices, this is a hard time. For the tens of thousands of families who do not have the financial resources to make these choices, this is a life-threatening time. Families are stuck with schools with too many children, not enough adults, no librarian, no books, and a nurse who only comes to the school once a week.

The Solution

The innovation and impetus for Philadelphia’s school-based health clinics (SBHCs) is a modification of the convenient care clinic (CCC) model of strategically placing medical care where people frequent. This model breaks down the barriers health consumers face in accessing traditional healthcare. With the placement of healthcare in retail areas such as drugstores, patients are able to seek immediate care without the burden of scheduling doctor's appointments, driving to the office and waiting long periods of time to be seen. Additionally, many of these clinics operate in close proximity to a pharmacy, making prescription pickup simple and easy. The success of the CCC model in providing the general population with more accessible healthcare served as the impetus for placing health clinics in schools, where children spend the majority of their time. Education Plus Health, a nonprofit organization, focuses on integrating pediatric primary care and preventive health into school infrastructures. The organization focuses on increasing young people’s access to affordable, convenient healthcare. Children face a unique set of obstacles in obtaining proper healthcare because they are not the administrators of their care; they rely on their parents and caretakers to provide their basic health needs. Parents and caretakers, however, may not recognize the need for preventive health services like vaccinations or sick care like treating a cold. Parents are also responsible for taking children to the doctor and paying any associated medical costs. Many times, these circumstances leave children without proper care. Education Plus Health provides many of the services that children need directly in the school setting. The purpose of the school-based clinic is not to replace a child’s existing primary care service but rather to supplement it when health needs aren’t being met.

Education Plus Health is currently in its third year of practice at the Belmont Charter School. The program started in 2010 at Pa,n American Charter School, which has since transitioned to a licensed practical nurse model. Both of these schools serve about 1200 students yearly, and 98% of the student populations are eligible for free or reduced-cost lunches. Of the students who attend both schools, 85% are Medicaid beneficiaries.

The school clinic operates much like the traditional school nurse model, except the office is staffed by a nurse practitioner (NP) and a medical assistant, which allows for more comprehensive care than a traditional school nurse can provide. An NP can practice broader services than can a registered nurse, diagnosing, treating, and writing prescriptions. NPs see children for both preventive care such as vaccinations, screening exams and physicals and sick visits such as asthma attacks and general illness. School NPs can also help manage chronic conditions through treatment plans and education to engage families in healthcare. The nurse practitioner and medical assistant care for about 40 students a day. They see children for sick care, preventive health and mental health reasons. They also conduct home visits, and provide the students with health newsletters and educational resources for parents.

Scaling

Building on the current success of the program, Education Plus Health has plans to expand on the services they offer their students. Currently, dental services are offered two days a year in the clinic; this year, though, the program is planning to expand these services and provide preventive dental care more frequently throughout the school year, such as administering fluoride to high-risk children. Education Plus Health also recognizes the need to address children’s mental and social well-being. Mechanisms are in place to address the difficult social and behavioral problems adolescents face. These mechanisms consist of teachers or healthcare providers referring children to social workers for treatment and evaluation. The school-based health clinic wants to integrate more streamlined care for these situations. For instance, integrating Philadelphia’s Children’s Crisis Treatment Center into the offered services would get students the definitive care they need more quickly than if they had to go through case workers.

Social Return on Investment

The measurable benefit of the program is quite compelling. In the first year of implementation, Pan American Academy’s student ER visits dropped to 0, and the number of students with 10 or more unexcused absences decreased from 129 in 2009–2010 to 2 in 2010–2011. In the third year of implementation, the schools are still experiencing similar metrics. Of the Belmont Charter School students with asthma, 55% improved their attendance after two years at the school, and by year three, 58% had improved their attendance rates. These data show the direct benefits of SBHCs. However, the actual social and financial benefits from the clinics far exceed improved attendance rates.

There are important indirect implications of school-based health clinics. Many parents of the students who attend Belmont Charter School and Pan American Academy work jobs that don’t offer paid sick time or vacation, making it difficult for these parents to get their children to doctors for care. Caring for sick children, especially those who have poorly managed chronic conditions such as asthma and diabetes, can require many visits to the doctor and missed days from work that can jeopardize the parents’ employment. Additionally, parents may not have the capacity to bring their children to their primary care physician appointments because of transportation issues or their own personal medical illnesses.

Proper management of chronic, preventable health conditions has long-standing effects that benefit individuals and society. For example, vaccinating children against preventable diseases not only protects them but also has huge societal implications. Relatively speaking, vaccinations are inexpensive compared with certain diseases’ potential medical costs. For instance, children are vaccinated against the poliovirus at 18 months old and then again during secondary schooling. Polio outbreaks are nearly unheard of, but that’s because of aggressive vaccination policies that led to its successful eradication from the U.S. in 1979. Before that, polio was one of the most feared diseases of the 20th century because its effects were so devastating, ultimately leading to paralysis and death (Post-Polio Health International, n.d.).

If polio were still around today, the financial and social costs to society would be insurmountable. A retrospective risk analysis done in 2006 estimated that, “the United States invested approximately US dollars 35 billion (1955 net present value, discount rate of 3%) in polio vaccines between 1955 and 2005 and will invest approximately US dollars 1.4 billion (1955 net present value, or US dollars 6.3 billion in 2006 net present value) between 2006 and 2015 assuming a policy of continued use of inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) for routine vaccination. The historical and future investments translate into over 1.7 billion vaccinations that prevent approximately 1.1 million cases of paralytic polio and over 160,000 deaths (1955 net present values of approximately 480,000 cases and 73,000 deaths). Due to treatment cost savings, the investment implies net benefits of approximately US dollars 180 billion (1955 net present value), even without incorporating the intangible costs of suffering and death and of averted fear” (Thompson & Tebbens, 2006). Preventive health services are meant to protect individuals and society, and making them available in school health clinics can only increase compliance with vaccination schedules and hopefully prevent more illness and undue burden on children and society.

The care provided to children also extends much further than basic healthcare. Dale Ayton, the nurse practitioner for Belmont Charter School, explains that that the school-based health clinic “provides children with a safe place to access; if the child isn’t feeling well, we will care for them; if they’re having a bad day, they can visit.” SBHCs provide children with comprehensive care. Ayton explained that children can visit her office for more than just medical needs, and she also explained the added benefit of being able to monitor the kids throughout the day: “We can see if there’s an ongoing problem. We spend the most time with the kids, so if a problem develops, we can catch it early and treat it.” Ayton recounted a recent incident: “A child was put on antibiotics and was having an allergic reaction to them—that can become very serious very quickly. It was noticed early in the school day, and we were able to get a prescription for steroids called in to the pharmacy, picked up and administered to the child. The child’s mother was bedridden at the time and wouldn’t have been able to take her to the ER. We avoided a costly ER visit for the child”

Financial Sustainability

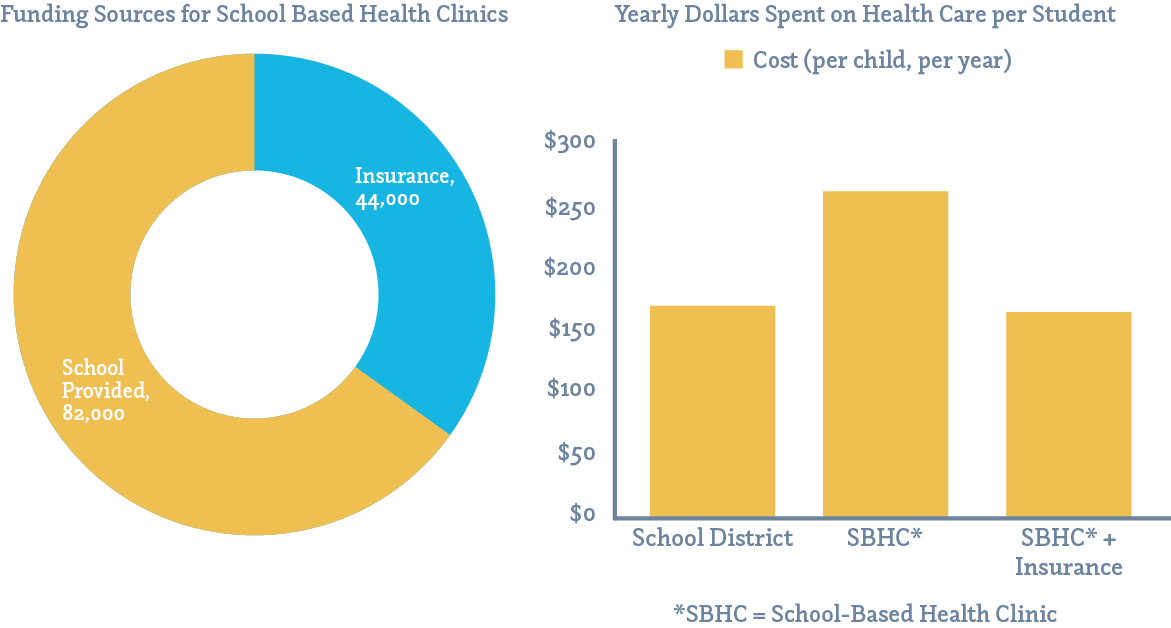

Education Plus Health is a financially sustainable model of nurse-managed care that has successfully married two services that are essential to the development of Philadelphia’s children. A school-based health clinic costs about $126,000 to start and operate. For the school, the responsibility for covering the salary of a standard nurse is $82,000. Education Plus Health subsidizes the remaining salaries needed to employ an NP and a medical assistant. Until recently, Education Plus Health secured private grants and funds for this purpose; however, they recently negotiated reimbursement for basic medical care from Keystone Mercy, the largest Medicaid-managed healthcare provider in Pennsylvania.

Keystone will now reimburse the SBHC $30 for every sick visit and $60 for every well-being check-up, adding $44,000 in yearly revenue. These modest reimbursement fees currently cannot cover the entirety of the NP and medical assistant salaries and clinic equipment, but they do set the foundation for a sustainable model of delivering primary care services to Philadelphia schoolchildren. That is to say, eventually this model can be implemented in the School District of Philadelphia for less money per student than the current system with the help of insurance reimbursement. SDP spends about $164 per student per year on nursing staff. The cost of an SBHC is $264 per student per year, but with the Medicaid reimbursement, the adjusted cost of the clinic is $160 per student per year, saving the school district about $4 per student per year and providing high-quality primary and preventive health services. It is likely that as more insurers reimburse Education Plus Health, the cost per student per year will drop substantially.

Education Plus Health Equals Community Schools

Education Plus Health’s school-based health centers serve the “whole child” and have the capacity to serve whole families and communities. Schools are charged with improving students’ academic outcomes through teaching and learning. In addition to academic knowledge, social and emotional growth can be inhibited by physical and mental health issues, hunger, and other issues related to living in poverty. In some underserved neighborhoods, the public school serves as the only community hub that can offer critical social services.

The community school model offers the opportunity for schools to address the whole child and not simply academic needs. “A community school is both a place and a set of partnerships between the school and other community resources. Its integrated focus on academics, health and social services, youth and community development and community engagement leads to improved student learning, stronger families and healthier communities” (Medina & Leach, 2014). Schools become centers of the community that are open to everyone—all day, every day, evenings and weekends.

Belmont Charter School and the eight universal charter schools have the potential to serve as true community schools and potential models for the public schools in Philadelphia. For example, Audenried Charter High School, located in the Grays Ferry neighborhood in South Philadelphia, could eventually serve as a community-based health center and offer critical services to surrounding community residents.

School-Based Health Centers: Filling Other Needs

Currently there are eight community health centers run by the city of Philadelphia. They are strategically placed throughout the city to provide residents with affordable primary and preventive health services. Although they are very useful to city residents, and offer an array of low-cost services, they are generally overcrowded and understaffed and can be difficult to access. If SBHCs become sustainable and systematic in the Philadelphia school system, the implications and scale could be astounding. Schools could have health centers that were open to members of the community. Instead of traveling 45 minutes to the closest city-run health clinic, neighborhood residents could just go to the local high school for care. This ambitious scale is futuristic at best, but could offer a very innovative solution to a multitude of problems surrounding medical care access.

The Opportunity to Serve Philadelphia’s Public Schools

In September 2013, sixth-grader Laporshia Massey died of what her father described as an asthma attack after falling sick while no nurse was on duty at Bryant Elementary School. In May 2014, during the same school year, Sebastian Gerena, a seven-year-old first-grader collapsed and died at Jackson Elementary School. Jackson did not have a full-time nurse, but one came every other Friday (Medina & Leach, 2014). Many Philadelphia residents and community leaders including School District Superintendent Dr. William Hite have decried the lack of full-time nurses as an injustice.

“In 2013, K-12 education enrollment in schools run by the School District of Philadelphia fell nearly 6 percent, the largest percentage drop in many years. At the same time, the number of students in publicly funded charter schools continued to rise, and enrollment in schools run by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia was little changed after years of steady, gradual decline.” Families are continuing to flee the school district and now the city because of the influx of options that provide resources including full-time nursing staff.

In general, the biggest cost-related barrier to the nurse practitioner model is schools’ lack of willingness to pay for the desired personnel. With the funding crisis, it could be next to impossible to employ the NP care model. Yet based on projections provided by Education Plus Executive Director Julie Cousler Emig, the Education Plus model could actually save SDP critical funds because the district could reduce school nursing costs and provide increasingly more robust services to students and families by hiring non-union registered nurse practitioners.

Disruptive Innovation

A major barrier for SDP to implement the school-based health center model may be political rather than financial. Currently, the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers (PFT) represents school nurses, and SDP is in contentious contract negotiations with the PFT for teacher contracts. This may be a politically strategic time to negotiate to reduce union nurse placements and replace them with the NP-led model.

Conclusion

Education Plus Health has the ability to eliminate a critical barrier to student success while improving health outcomes for poor students and families. This innovative model can also change the way healthcare is provided in communities in which healthcare service utilization is low. This refreshing approach to two intertwined and systemic problems is promising and couldn’t have come at a better time. The children of Philadelphia have a right to both basic healthcare and educational success.

References

- The Baltimore Student Attendance Campaign and Elev8 Baltimore. (2012). State of chronic absenteeism and school health: A preliminary review for the Baltimore community. Baltimore, MD. Retrieved from http://www.elev8baltimore.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/Absenteeism-and-School-Health-Report.pdf

- Medina, R., & Leach, S. (2014, May 23). Student, 7, passes out at Andrew Jackson School and dies two hours later. Philly.com. Retrieved from http://articles.philly.com/2014-05-23/news/50033091_1_counselor-principal-bird-calls

- Post-Polio Health International. (n.d.). Poliomyelytis. St. Louis, MO. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/downloads/polio.pdf

- Public Health Management Corporation Community Health Data Base. (2007). Data findings: The use and affordability of dental care for children in SEPA. Philadelphia, PA: A. Gordon. Retrieved from http://www.chdbdata.org/datafindings-details.asp?id=50

- Thompson, K. M., & Tebbens, R. J. D. (2006). Retrospective cost-effectiveness analyses for polio vaccination in the United States. Risk Analysis, 26(6), 1423–1440. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6924.2006.00831.x

Contributing Interviews

Julie Cousler Emig, MSW, LSW, Executive Director, Education Plus Inc.

Dale Ayton, CRNP, PMHS, Pediatric Nurse Practitioner, Clinical Program Coordinator, Belmont Charter Schools Wellness Center

Nancy Rothman, EdD, RN, Independence Foundation Professor of Urban Community Nursing, Director of Community-Based Practices, Dept. of Nursing, College of Health Professions and Social Work, Temple University

Tine Hansen-Turton, CEO, National Nursing Centers Consortium, Chief Strategy Officer, Public Health Management Corporation