Executive Summary

Day laborers and domestic workers -- low-wage, contingent, and mostly immigrant workers -- are some of the most marginalized populations in Chicago. Most day laborers earn minimum wage or less, and among domestic workers, wages as low as three to five dollars an hour are common. Latino Union's innovative worker-run hiring hall at the Albany Park Workers Center is offering these workers the opportunity to connect with employers, begin using written contracts, and find living-wage work.

Instead of seeking employment on public sidewalks or through often-abusive agencies and middlemen, workers access a daily job distribution list and collectively market their work. A coordinator helps facilitate the hiring process between workers and employers. The Center’s average wages in the 2015-16 program year were $32 an hour -- three times Chicago’s minimum wage; 30 percent of participants reported that they increased their number of repeat clients, personal clients, and/or referrals; and 28 percent of program participants went on to find permanent or semi-permanent jobs, with average wages of $21.72 an hour.

Responding to the Challenges of Low-Wage Industries

An emerging workers’ rights movement has drawn attention to the challenges faced by low-wage workers in informal sectors, including low pay, employers who abscond without paying workers, underemployment, a lack of opportunities for career mobility, sexual harassment, safety risks, verbal abuse, and retaliation against workers who organize.

This movement is driven by community-based “worker centers,” nonprofit organizations that support low-wage workers in addressing labor issues. Best practices among worker centers include sector-based organizing, where nonprofits serve specific workers in specific sectors with large concentrations of low-wage workers, high incidences of abuse, and the potential for policy reforms (Cordero-Guzman, 2014).

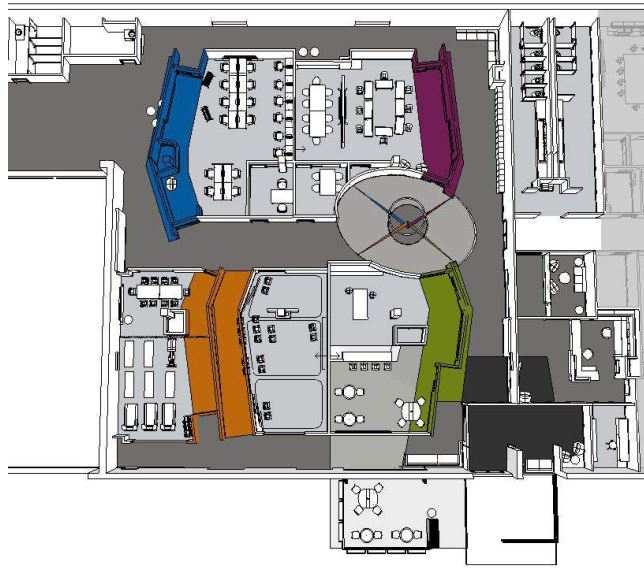

Though rooted in systemic policy issues, many of these challenges can also be addressed at the individual level. The Chicago-based Albany Park Workers Center, a worker-run, living-wage hiring hall, offers a model solution for improving workers’ individual career outcomes while engaging them in advocacy to create systemic change in their industries.

The program serves Chicago’s day labor and domestic work industries, which are rife with wage theft, employer abuse, and hazardous working conditions. Day laborers are low-wage, mostly immigrant workers who gather at seven street corner hiring sites around Chicago. At the corner, they wait for contractors, residents, and business owners to hire them for construction, landscaping, and moving work. Waiting at the corner leaves them unable to access traditional workforce development programs and vulnerable to immigration raids and police harassment (Valenzuela et al, 2006).

Domestic worker Lucia Wrooman speaks at 3.8.16 ceremony to open APWC hiring hall to domestic workers

Domestic workers are overwhelmingly women of color and/or immigrant women who work in private homes as nannies, housecleaners, caregivers for the elderly, and personal care assistants for people with disabilities. Domestic workers in most states lack the same workplace protections that are standard for other workers, such as a state minimum wage, breaks, and protection from sexual harassment. (Burnham and Theodore, 2012). In the Chicago area, wages as low as three to five dollars an hour are common.

In addition to these longstanding challenges, Albany Park’s day laborer community faced a crisis in 2003 when Chicago police and a local alderwoman shut down and fenced off a longstanding hiring site, a devastating loss of a physical space that generated thousands of dollars a year in income for workers who depended on it. Facing these challenges, displaced day laborers created the Albany Park Workers Center in 2004. In March 2016, the Center expanded to include domestic workers.

At the Intersection of Collective Bargaining, Cooperative Economics, Ethical Consumption & Job Training

The Albany Park Workers Center’s collective wage scales and contracts have updated the idea of collective bargaining for the age of the informal, temporary gig economy. Day laborers and domestic workers collectively set minimum wage rates for different types of jobs; individual workers are free to negotiate higher wages based on their skills and experience. This system has resulted in average wages of $32 an hour for jobs that come through the hiring hall.

The Workers Center program is governed by the Latino Union members who seek jobs through it. In monthly meetings, members propose, debate, and vote on rule changes, including how the daily job list lottery works, marketing, and requirements for participation. Programs engage members in continuous improvement through a collaborative cycle of action, reflection, and testing new ideas.

The program is staffed by a coordinator who replies to calls and emails from prospective employers; collects job details; supports workers in following the Center’s health and safety code; and runs a daily lottery to determine the order in which workers are offered incoming jobs each day. Once a worker has negotiated job details with an employer, the coordinator prepares a written contract and enters details into the center’s data system for ongoing evaluation of hourly wage rates, overall earnings, demand for skills, and employer satisfaction.

Employers pay the worker directly, eliminating the need for the program coordinator to administer wage collections and payments. Following a job’s completion, the coordinator surveys employers, asking them to rate their satisfaction and offer ideas for improving the program which are then suggested to worker members. The coordinator also encourages satisfied employers to call the worker directly for future jobs, rather than calling the Center, ensuring that workers with satisfied customers can work more independently and reduce their reliance on the program.

For workers with multiple barriers to employment, the coordinator also offers ongoing coaching on negotiating with employers, problem-solving around issues such as transportation, language interpretation, and other soft employment supports. While waiting for work and outside of Center operation hours, workers access drop-in workforce development training including workplace English classes; trainings in customer service; workplace safety trainings; and peer and expert-taught workshops in hard skills such as green cleaning, CPR (a critical marketable certification for nannies and home care workers), drywall, painting, moving and other construction and home maintenance topics. In combination with the Center’s wage scale, trainings have created a career lattice in which workers can increase their earnings and expand their skills to include new areas of work over the course of their time participating in the program.

To enter the daily job lottery, workers are required to participate in weekly outreach to employers, in which thousands of postcards advertising the program are distributed in neighborhoods around Chicago. While the Center is not a worker cooperative, its collective marketing and branding means that every worker’s performance, good or bad, influences consumer perception and the likelihood that an employer will recommend the program to others. This automatic feedback loop drives high performance overall – employers rate their satisfaction as 8.8 out of 10, on average -- and ensures that when a customer service issue does arise, workers rapidly resolve it and hold each other accountable.

One key challenge for the Albany Park Workers Center and any similar program is that its impact (number of workers served and earnings) depends on the resources that are available to market the program to employers. Workers who are not hired within a few days of showing up at the hiring hall will become discouraged and leave. Just as any ecosystem has a carrying capacity, programs that have found a certain market niche and employer base will rarely be able to expand without a substantially increased investment in marketing to new groups of employers. Therefore, organizations seeking to implement a similar program must beware of the nonprofit starvation cycle (Gregory and Howard, 2009) and continually invest in marketing in order to ensure a successful program.

The Center occupies a unique market space as an alternative to street corner hiring sites and domestic worker hiring agencies. Employers are primarily homeowners who are looking for support with maintenance, landscaping, moving, or house cleaning. They are attracted by the ease of contracting a worker from the Center, since the center offers a support system and guarantee of quality that street corner hiring sites and bulletin boards do not.

Many also turn to the Center because they want to be ethical employers. Homeowners are increasingly aware that employment in informal sectors is fraught with legal and ethical issues; that domestic worker agencies provide little of the fees they charge to the workers themselves; and realize that workers do not have the expertise needed to navigate employment law. The Workers Center’s collective wage rates and lawyer-reviewed contracts offer them a solution and guarantee that workers in their home are receiving fair pay.

As for workers, the Center offers outstanding benefits that address some of the most urgent problems workers face. In addition to virtually eliminating accidents and wage theft, the Center connects workers with living-wage employers hundreds of times per year; provides a warm, safe space to seek work away from the police officers, immigration agents, and sometimes hostile business owners who often disrupt street corner hiring sites; and provides a sense of community in industries where many workers are immigrants, working in isolation and living apart from family.

Latino Union’s hiring hall program is funded primarily by workforce development grants, as well as $30 annual dues paid by each of the organization’s members. While it’s laudable that many workforce development funders are now seeking to create pathways for workers to access career training for high-demand, middle-skilled jobs, it bears asking what workforce development programs can support workers in informal industries who are unable to access higher education due to low literacy levels, ineligibility to enroll in Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act-funded programs, lack of documentation, family responsibilities, and language barriers. The Albany Park Workers Center model offers one possible answer.

Works Cited

Cordero-Guzman, Hector R. 2014. “Community-Based Organizations, Immigrant Low-wage Workers, and the Workforce Development System in the United States.” Grantmakers Concerned with Immigrants and Refugees.

Gregory, Ann G. and Howard, Don. “The Nonprofit Starvation Cycle.” Stanford Social Innovation Review 7, no. 4 (2009):49-53

Valenzuela, Abel; Theodore, Nik; Meléndez, Edwin; and Gonzalez, Ana L. 2006. “On the Corner: Day Labor in the United States.” Center for Urban Economic Development.

Burnham, Linda and Theodore, Nik. 2012. “Home Economics: The Invisible and Unregulated World of Domestic Work.” National Domestic Workers Alliance

Author Bio

Rebecca Harris is Latino Union’s Development and Communications Manager. Rebecca is a 2008 graduate of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism; before joining Latino Union, she worked as an investigative journalist covering Chicago Public Schools for Catalyst Chicago magazine.