Summary

People with Serious Mental Illness, SMI, live on average 25 years less than others, often due to chronic medical conditions. Heartland Health Centers provides primary care to people with SMI in the facilities of partners Trilogy Behavioral Healthcare, Thresholds, and Community Counseling Centers Chicago. From checkups to psychiatry to shared medical records, we collaborate intensively. These partnerships have shown patients do better on weight loss, smoking cessation, blood pressure and other indicators, while patients’ satisfaction with their care increased. But care integration for people with serious mental illness remains rare in Illinois and beyond. This article documents key components to successful partnerships and highlights barriers to scaling-up integrated care.

Article

Track star Julius Mercer, who receives integrated primary and mental-health care from Heartland Health Centers and Trilogy Behavioral Health Care, is now an author and inspirational speaker.

Photo Credit: Heartland Health Centers

“I was sick by myself,” says Julius Mercer. “I could soar high with the help of other people.”

Support from family and friends helped Mercer become a track and field All-American in the 1980s, alongside stars like Carl Lewis. Knee inflammation kept Mercer from the Olympics. Then, his life unwound due to an untreated bipolar affective disorder that led to substance abuse, then four years in prison.

Since 2014, Mercer has benefited from integrated care, defined as systematic coordination of general and behavioral healthcare by the federal Center for Integrated Health Solutions. For Mercer, integrated care means, between appearances as an inspirational speaker and self-published author, he travels to one location to get combined services and visits weekly to check in.

While there he can see his therapist, pick up prescriptions at the on-site pharmacy, and see his primary-care medical provider. His providers also share medical records, while involving Mercer in his care. For example, high cholesterol spurred the former athlete to go to Zumba and start a diet. “I dropped 13 pounds in the past nine months,” he says.

Background

For decades, people with Serious Mental Illness, SMI, received little attention even as others gained access to care. In 2006, the National Association of State Mental Health Directors showed people with SMI had 25 years lower life expectancy.1 A 2012 study found people with SMI were 3.4 times more likely to die from heart disease, 3.4 times more likely to die from diabetes, 5 times more likely to die from respiratory ailments, and 6.6 times more likely to die from pneumonia and influenza.2

Chicago’s North Side had 60,031 behavioral health hospitalizations in 2011, almost twice as many as for heart disease (33,689). In Rogers Park, mental health disorders account for the largest portion of hospitalizations.3 Meanwhile, community-based care for people with SMI is a growing need. Medicaid expansion and the move to managed care have expanded primary care coverage for many in Illinois. Federal judges in the Ligas, Williams and Colbert cases upheld the right of individuals with disabilities to live in the community, driving a parallel expansion for community mental health services.4

Founded in 1993 as part of Heartland Alliance, and incorporated in 2005, Heartland Health Centers is a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) offering affordable and comprehensive primary care, oral health care, and mental health care services. Since 2013 it has been accredited and designated as a Primary Care Medical Home by the Joint Commission. Heartland Health Centers has 16 locations serving Chicago’s North Side and suburbs. In 2016, Heartland Health Centers treated 23,000 patients. Behavioral care accounted for 15 percent of nearly 90,000 patient visits to all clinics.5

Heartland Health Centers seized an opportunity in 2010 to improve the health of people with SMI by partnering with Trilogy Behavioral Healthcare in a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) integrated care demonstration program to help people with SMI. From 2010 to 2014, more than one thousand clients participated. Those who completed an assessment using National Outcome Measures developed by SAMHSA demonstrated improved outcomes. These included weight loss, cholesterol and diabetes, and blood pressure improvements; and quitting smoking.

The partnership received an Integration Award from National Council for Behavioral Health in 2014. Heartland Health Centers and Trilogy have continued to collaborate, and Heartland Health Centers expanded to work with Thresholds and C4. These partnerships have also shown results. For example, over a 10-month period at Thresholds, patients’ blood pressure control improved from 38 percent to 71 percent.

Heartland and Trilogy are among only a small number of the agencies to participate in that demonstration program to continue providing integrated care. Providing integrated care requires a series of shifts in operational thinking, collaborative practice, and organizational culture. Plus, current Medicaid reimbursement and financial systems dis-incentivize integrated care.

Improved Outcomes

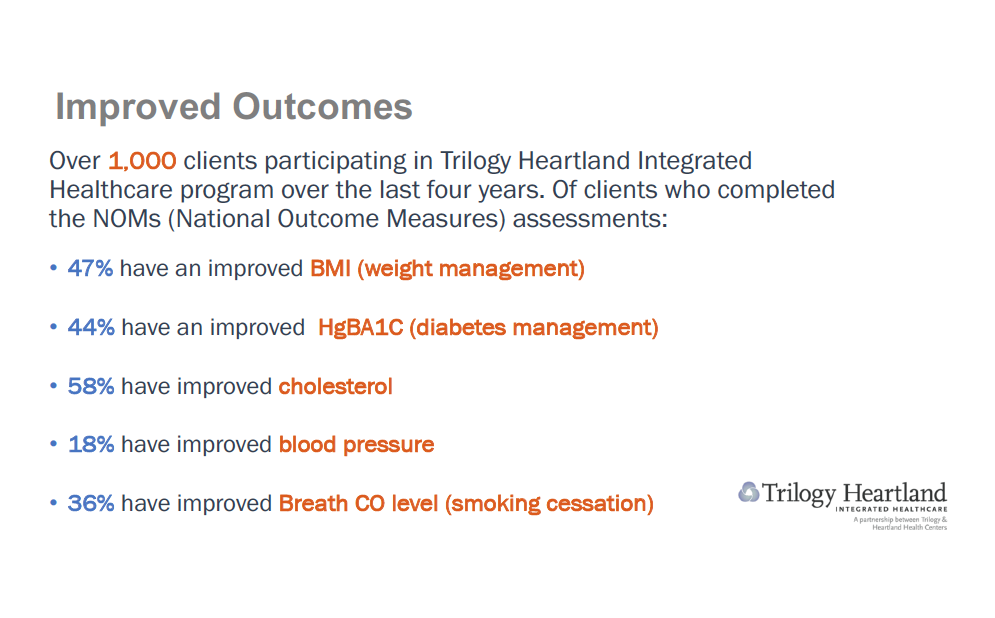

More than 1,000 clients participated in Trilogy Heartland Integrated Healthcare program over the last four years. A significant number of clients experienced health improvements on a scale developed by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s, the National Outcome Measures of progress toward mental health and recovery from addiction.

Photo Credit: Heartland Health Centers

Integrated-Care How-to: Added Attention, More Teamwork

The first shift to provide excellent integrated care is spending more time with a vulnerable population: Extra time and sensitivity is required to get results for patients with SMI. “Patients with SMI come with a more complex list of challenges so they benefit from a more holistic approach,” says Laurie Carrier, MD, Heartland Health Center’s chief medical officer. Even a few extra minutes, she says, builds rapport.

For a new patient, Carrier says, she may delay invasive screenings and procedures to build trust if she judges it might cause the patient to abandon treatment. Carrier and other providers also see patients more often -- nine to 11 visits a year on average compared to two to three visits a year on average for all patients.

Another shift is the nature of collaboration between primary & behavioral health care centers. Teamwork by primary care and mental health providers, and pharmacists leads to “gold standard” care for people with SMI, says Alice Geis, DNP, APN, Director of Integrated Health at Trilogy Behavioral Healthcare, assistant professor at Rush University College of Nursing, and a psychiatric nurse practitioner. This includes connecting patients to care and sharing insights about patients’ needs and how they respond to treatment across different organizations and among staff with different training and experiences.

On-site pharmacists at Trilogy deliver medications, which helps prevent harmful combinations and avoid overly complex regimens. Assertive Community Treatment staff do outreach to ensure patients get to their appointments and share insights about each patient with providers. Plus, shared access to medical records from both mental and primary health centers keep everyone up to date on each case.

Openness to shared decision-making and compatible organizational cultures are essential to integrated care. But partnerships between primary and mental health centers can be hard to initiate and sustain. “It takes intense focus for two cultures working together to try to bend the mortality ratio for people with serious mental illness,” says Sheila O’Neill, LCSW, vice president for Care Integration, Thresholds. For example, when it came time to hire new providers to staff the integrated Heartland-Thresholds integrated center, O’Neill proposed jointly interviewing candidates: “Heartland said, ‘Absolutely! When can we start?’” she recalls. To achieve that level of coordination, leaders from the partnering agencies meet on a monthly basis.

Scaling up: Changing How We Measure, Reimburse Care

More than 90 percent of America's health plans use HEDIS, Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set, to measure performance. But HEDIS measures may not apply perfectly to treatment outcomes for people with SMI. Outcomes HEDIS currently fails to capture include Assertive Community Treatment outreach teams’ ability to connect people to care and patients’ quality of life measures.

Both are key to better care for people with SMI. Another measurement that is hard to come by: per-patient total expenditures. More visits and services can increase expenses to care for people with SMI. But integrated care can also reduce emergency-room visits and prevent expensive interventions, which lowers total per-patient cost. If insurers in Illinois provided per-patient data, it would be easier to demonstrate and evaluate savings of the integrated-are model.

Another issue: reimbursement to primary and mental health centers has evolved separately. Each gets reimbursed for similar services at differing rates, via different billing methods and codes. There is minimally sufficient funding for psychiatry and primary care, but funding for licensed clinical social workers, counseling, and support services currently are inadequate.

Another funding related issue is that integrated care programs lack support to get up and running. Heartland Health Centers and its partners rely on grants and individual contributions for expenses related to this work. For example, in 2016 Thresholds used private funding to build-out a primary care clinic that Heartland Health Centers now rents. Ongoing costs also include staff time for coordination time by institutional leadership. None of these costs are covered by existing reimbursement formulas. Currently Heartland Health Centers and its partners are working with Health and Medicine Policy Research Group on a financial feasibility study that may clarify these issues and lead to new recommendations.

Conclusion

We have found providing behavioral health and primary care together delivers more effective treatment. The health of people with SMI can be more complex with more diagnoses, but integrated care is helping them live longer and improve their quality of life. This article shows it can be done, now it’s time to bring these innovative collaborations to scale.

End Notes

1 "Morbidity And Mortality In People With Serious Mental Illness | National Association Of State Mental Health Program Directors." 2006. Nasmhpd.Org. Accessed April 8, 2018. www.nasmhpd.org.

2 Hardy, S. & Thomas B. 2012. "Mental And Physical Health Comordibity: Political Imperatives And Practice Implications. - Pubmed - NCBI ". Ncbi.Nlm.Nih.Gov. Accessed April 8 2018. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

3 Anonymous. 2016. Cityofchicago.Org. Accessed April 8 2018. www.cityofchicago.org.

4 For an overview of these three cases, see: Anonymous. Oct. 4, 2016. “EFE’s Recent Work,” Equip for Equality. Accessed April 8 2018. www.equipforequality.org

5 2017. Anonymous. “Annual Report.” Heartlandhealthcenters.org. Accessed April 8, 2018. www.heartlandhealthcenters.org.

Author Bios

Gordon Mayer, principal of Gordon Mayer Communications, is a writer and storyteller who has been ensuring all stakeholders have voice in shaping effective and fair policy for more than 20 years. He has a Master’s Degree from the University of Chicago.

Molly Bougearel is Vice President for Strategy & Development at Heartland Health Centers. She has a Master’s Degree in Public Health Policy and Administration from the University of Illinois at Chicago.