Executive Summary

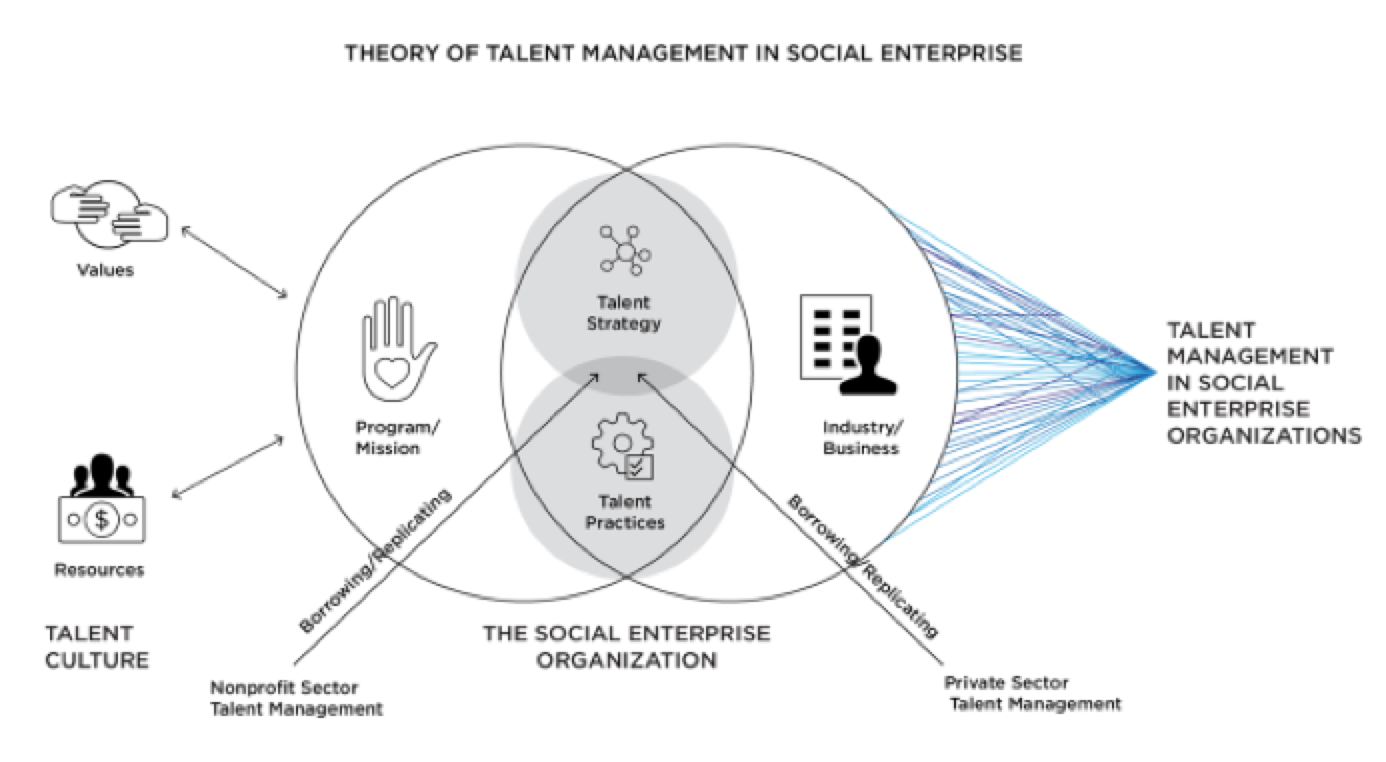

This article is a summary of a dissertation research study to investigate the state of talent management within the context of social enterprise organizations, through the lived experiences of organizational leaders and teams in 15 diverse organizations across North America. I used a qualitative grounded theory approach to address the research question: to what extent are nonprofit social enterprises using talent management philosophies, principles, mindsets, and practices? Semi-structured interviews, conducted with 26 participants from 15 organizations, were the primary source of data for the study. Study findings led to a grounded theory of talent management that included four concepts: (1) social enterprise is an organizational construct unto its own, resulting from the symbiotic program and business relationship; (2) talent management in the social enterprise construct is in an evolving state; (3) the goals are deeply rooted in social impact values; and (4) as talent management mindsets and practices coalesce within organizations, people borrow and replicate strategies and practices from both the nonprofit and the private sectors, resulting in a web of formal and informal approaches. Implications for practice were presented within the context of a Talent Management Imperative Model for the field of social enterprise, which emphasizes humanness and inclusion in the workplace and organizational effectiveness. It includes four principles: alignment with strategy, leadership engagement, inclusion upfront, and consistency and continuity, and seven practices: recruitment and selection, professional development, compensation planning, strategic workforce planning, performance management, retention, and succession planning.

Introduction

People are our greatest asset. This phrase is heard frequently in the social enterprise sector. What it really means is subject to a wide range of interpretations. Clarifying precisely how social entrepreneurs shape philosophies and practices centered on people within their organizations is the focus of this article and the dissertation research. The impetus for this research is to create awareness and understanding of the organizational practices and strategy around people (i.e., talent) that accelerate organizational effectiveness (i.e., the achievement of strategic social impact and revenue goals) and foster human-centered and inclusive workplaces.

The Role of Talent in Organizational Effectiveness

A brief discussion on the origins of talent as a strategy for organizational effectiveness helps put this research in context. Talent management is a central organizational effectiveness strategy in private sector firms, although there is no singularly agreed upon definition or model for the term talent management (Cappelli & Keller, 2014; Collings & Mellahi, 2009; Kim, Williams, Rothwell, & Penaloza, 2014; Ross, 2013; Tansley, 2011). As boundaries between private and nonprofit sectors blur, organizational effectiveness strategies from the private sector are often translated into social entrepreneurship practice (Dees, 2012; Grieco, Michelini, & Iasevoli, 2015). For the purposes of this research, talent management is defined as an organizational effectiveness construct rather than the transaction-oriented human resources business practices found most commonly in the sector. A talent management approach often begins linking all people practices to organizational strategy and includes (a) alignment with key business practices, (b) integration with organizational processes, and (c) inculcation throughout the organization as a distinct mindset (Silzer & Dowell, 2010).

Grounding Talent Management Theory in Practice

The research design for this qualitative study was grounded theory method. Grounded theory construction facilitated the ability to work with emergent concepts of talent management that were not fully understood or charted in the nonprofit social enterprise field (Charmaz, 2014). Three selection criteria were applied to recruit participating nonprofit social enterprises in the study: (a) the social enterprise had been in business for at least two years; (b) the CEO or ED had been in the position for at least 12 months; and (c) the enterprise had a commercial production and sales operation that served as the basis for a workforce development training program. Participating organizations were recruited through my professional network of colleagues in the nonprofit social enterprise field including (a) CEO/EDs, (b) consultants and advisors, (c) REDF, and (d) philanthropic investors. The recruitment process yielded primary interviews with 15 individuals at the president, chief executive officer, or social enterprise director levels of nonprofit social enterprises.

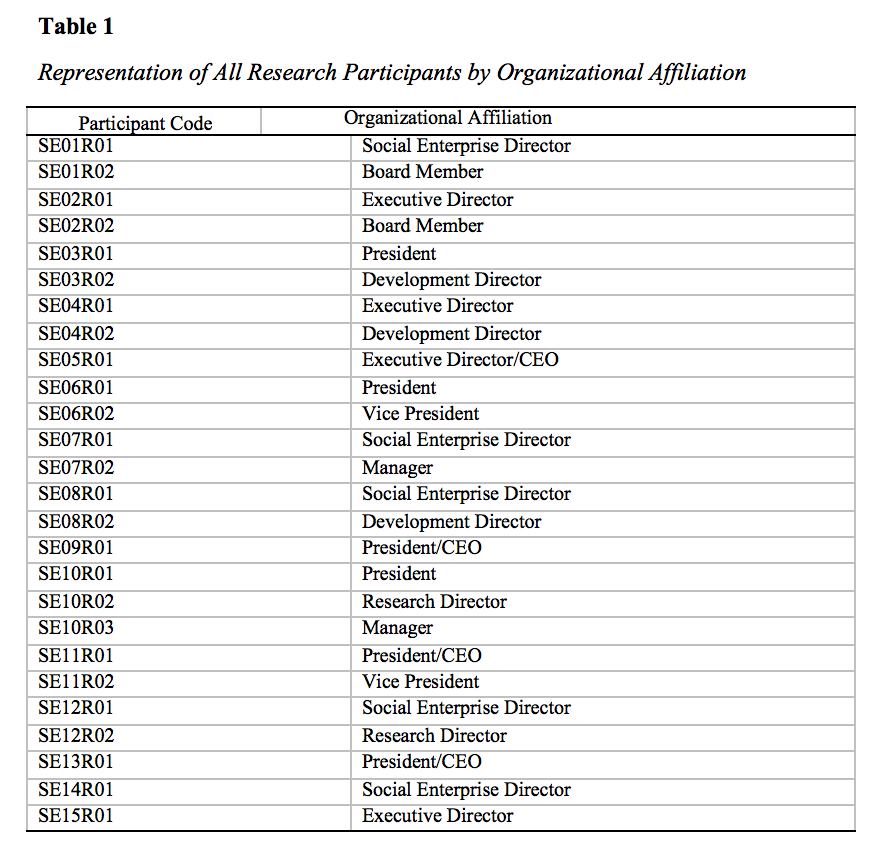

Each research participant was asked to (a) complete a brief survey on the scope and scale of the social enterprise organization, and (b) recommend an additional person(s) at the staff or board level of the organization who might add insight on the research question. In 10 of the 15 primary interviews, participants recommended additional staff and/or board members who might participate in the study. These recommendations led to 11 additional interviews, for a total of 26 interviews with research participants. The organizational affiliations of the 26 research participants and their organizations are listed in Table 1. Unique code identifiers are used to protect the anonymity of the participants and their affiliated organizations.

To provide a diversity of experiences related to the research question, and to assist in triangulating the findings, participants represented a cross-section of industry sectors including manufacturing, services, retail, and agriculture in multiple states across the United States and Canada. The markets served were direct-to-consumer or business-to-business on a local, national, or international scale.

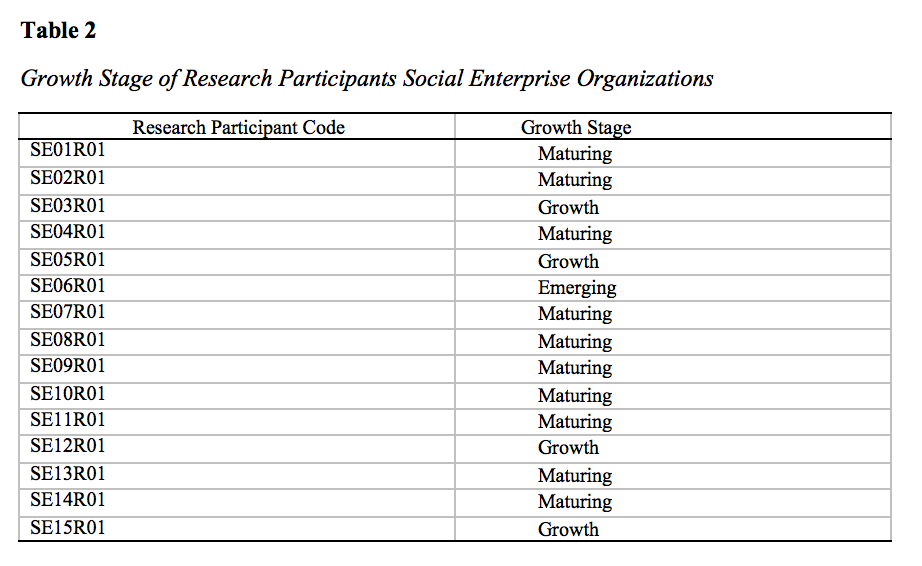

The study included organizations at the emerging phase (operating 1-3 years), growth phase (operating 3-7 years), and maturing phase (operating more than 7 years). The majority of the organizations (64 percent, n=10) were in the maturing phase (Table 2). The next largest group represented were organizations in the growth phase (29 percent, n=4), followed by the emerging phase (7 percent, n=1).

Emerging Talent Management Themes

Research participants engaged openly, and provided rich narratives throughout the interviews. The data generated from the 26 interviews, a background demographic survey, and a review of organizational documents provided a rich collection of experiences and perspectives on talent management. The data analysis process emphasized deep immersion in the data and multiple phases of coding and categorization of information to explore implications for theory and practice. The first step to categorize and code the data, initial coding, involved line-by-line review of the transcript and further analysis with NVivo 11 qualitative software. Each line of each interview was manually read and then coded both to general themes based on the interview questions, as well as to emerging themes discovered during the first part of the initial coding process. Nine initial themes or categories were generated through initial coding:

- Advancing Talent Management Practices

- Clarifying Talent Management Definitions

- Cultivating a Talent Management Culture

- Engaging in Strategy/Strategic Planning

- Leading with a Talent Management Philosophy or Mindset

- Sharing Key Learning for the Field

- Striving for Talent and Organizational Effectiveness

- Suggesting Additional Insights

- Utilizing Strategic Workforce Planning

A Varied Picture of Talent Management Strategy and Practice in Social Enterprise Today

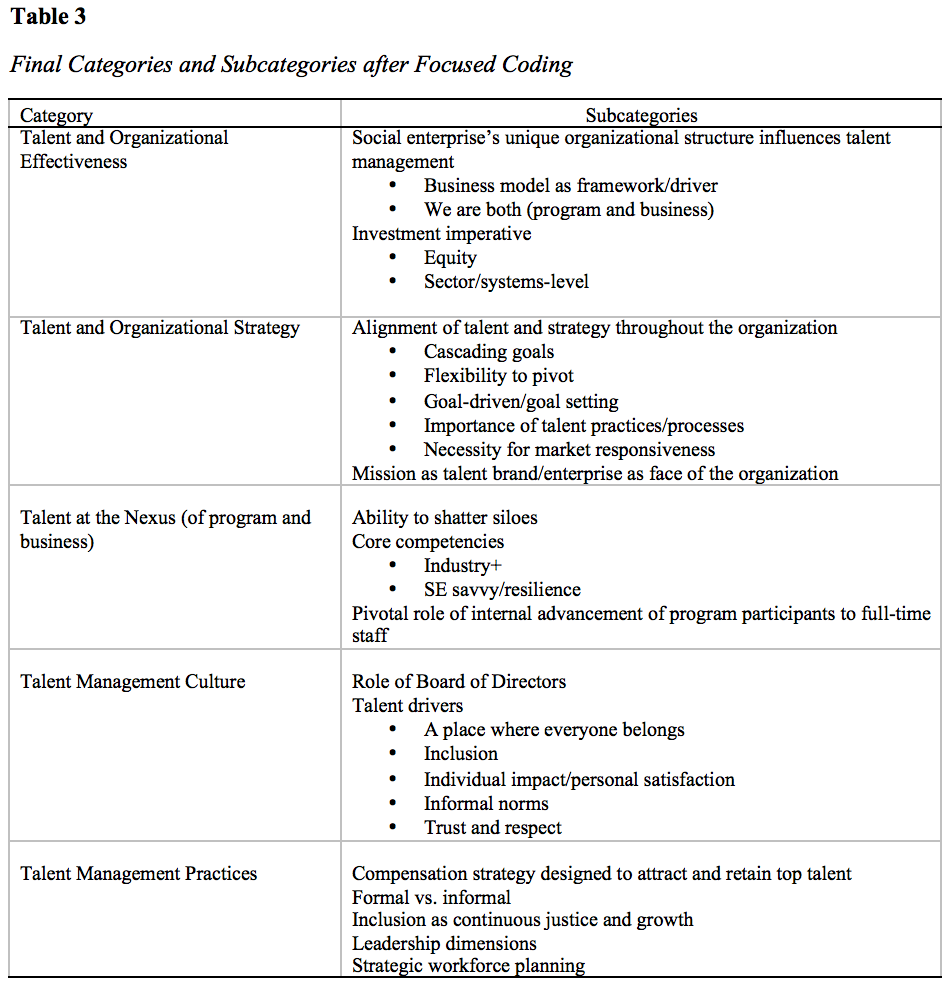

The data analysis continued with axial coding, where I merged, clustered, retitled, and eliminated categories, based on participant narratives, along with data from the survey, and review of organizational documents. The resulting five themes and 30 companion subthemes (Table 3) represent how talent management manifests in nonprofit social enterprise organizations. These five themes and a representative selection of participant insights and comments are presented in the following section.

1. Talent and Organizational Effectiveness

No other type of organization is more centrally situated at the nexus of social impact and business revenue imperatives than a nonprofit social enterprise. How people define and pursue organizational effectiveness within this interstitial construct was the subject of considerable discussion and contemplation by research participants. The ability of people to be set up from the onset of their employment throughout their tenure to achieve organizational effectiveness must be understood within this interstitial organizational construct. Comparing a person’s role in a social enterprise to a traditional nonprofit organization or a private sector firmly negates the unique nature of the social enterprise context and incorrectly ascribes the person’s role, charge, and challenge in achieving organizational effectiveness.

Social Enterprise’s Unique Organizational Structure Influences Talent Management

In the interstitial space of social impact and business revenue, research participants discussed how they define the social enterprise (i.e., either business or program). Most participants concluded that they fall in this interstitial space, defined, as “we are both.” As an organizational construct, the notion of “we are both” requires new and creative approaches to talent and organizational effectiveness, which may not currently be fully articulated or is still emerging in the social enterprise field.

… we struggled with the concept of, "Are we a warehouse first? Are we a social enterprise first?" And we came to the conclusion that we're both first. We do a great job, and we happen to feature [program participant background] as a part of our workforce. (SE07R01)

Investment Imperative

Participants described the urgency and need for investment in talent at all levels of the organization, in order to maintain and accelerate organizational effectiveness. The rationale for the investment centered on concerns of pay equity and the ongoing need to attract and retain people who can navigate the unique demands of a social enterprise workforce development context. On hiring a social enterprise director, SE06R02 stated:

The first person I hired was phenomenal, but left after less than a year. I was getting ready to hire the next person to run the enterprise. I thought I would hire a recent graduate, but a [experienced] professional became available at a higher rate than I expected. I realized that we would get more talent and more of a future with this person and we hired them. There is clearly an advantage to hiring more experienced, more talented people and paying them more. If there is one take-away from a talent management perspective that is what we are doing here.

Many participants expressed concerns around pay equity:

I firmly believe that the people trying to break the cycle of poverty should not be set up to live in poverty. Like it shouldn’t have to be a choice between helping and surviving, and I think that’s a broad statement around non-profits and social enterprises as well, where particularly at the junior role, those salaries are really tough. The whole industry…we benchmark against the industry (i.e. the nonprofit industry), but the whole industry is tough. (SE08R02)

2. Talent and Organizational Strategy

Participants discussed the role of talent and organizational strategy in two key ways: the alignment of people/talent and strategy through goals and individual engagement, and the role of the organization’s mission as a brand ambassador of sorts for talent, with the business enterprise as the face of the organization. Organizational strategy varied in social enterprise organizations as reported by research participants. The variations ranged from: (a) no recent strategic plan, (b) strategic plan exists, but is not used, (c) strategic plan used on limited basis for program or business, (d) strategic plan drives program or business goals, to (e) strategic plan drives both program and business goals.

Alignment of Talent and Strategy Throughout the Organization

Further variation in organizational strategy occurred when examining how talent management approaches and practices are presented in organizational strategy. Key themes on the alignment of talent and strategy included: (a) the overall importance of talent practices to organizational strategy and success, even if they were not fully developed, (b) the many ways in which individual and organizational goals were set, managed, and aligned, and (c) the importance of flexibility in strategic plans to pivot when external conditions change over time.

I don't think that a lot of not-for-profits, certainly us, really understand the whole talent issue and how to thoughtfully think through the talent that's required to execute the strategy and the business plan. And that lack of sophistication is not surprising because most people involved in social enterprises don't have that background or don't have access to people who think that way, who think strategically about talent, who think about what are the implications, what's the people part of the strategy plan, and how important it is to get the right people in the right place at the right time in order to execute it. (SE01R02)

3. Talent at the Nexus (of program and business)

Study participants repeatedly emphasized the unique talent needs, conditions, and requirements that were basic but essential to realizing organizational effectiveness as defined by meeting social impact and revenue goals. Themes and subthemes on the topic of talent at the nexus focused on the team’s ability to shatter silos between program and business, core competencies, and the pivotal role of internal advancement of program participants to full-time staff. Participants noted that although the social enterprise was one organization, there were schisms between the program and business units.

Ability to Shatter Siloes

Participants discussed the natural and unintended consequences of working at the nexus of two unique fields, represented by the program and the business. Participants described how this manifested within their organizations. Topics discussed included, but were not limited to, collaboration, competencies, cross training, competition, and cultural/social/industry linkage. The imperative for bringing these potentially disparate parts of the social enterprise, the program, and the business together through shattering siloes was pursued in a number of ways as discussed by the participants.

I’m conducting a symphony, of different music and different sounds and different things. I’m putting it together and making a song. The frustration always revolves around blending in parts of the job that you don’t see as your job. I’m forcing them to understand what the others do, cause they’re all interrelated. (SE10R01)

Core Competencies

Traditional competencies for social entrepreneurs were not adequate to convey the depth of the situational context within social enterprise organizations, as described by participants. The competencies needed to realize organizational effectiveness within the social enterprise workforce development context extend beyond what has been described in the literature. Two sets of competencies distinctive to social enterprise emerged in this study: (a) Industry+ and (b) Social enterprise savvy/resilience/true grit.

Industry+

Throughout the study, participants emphasized the importance of industry-based expertise. In examining the data, participants took the notion of industry expertise to a deeper level, termed Industry+. Industry+ incorporates a more distinct set of skills to address the organizational effectiveness needs of social enterprise organizations’ dual nature. Beyond industry-based expertise, Industry+ includes (a) deep knowledge to weather competition from multiple sources, including private sector companies with known brands, many of which are global; (b) strategic, mission-aligned skills (e.g., teaching) incorporated into market/industry-based functions/requirements; and (c) the ability to challenge status quo operations and functions internally within their own organizations.

Social Enterprise Savvy/Resilience/True Grit

Adaptability has been identified as a hallmark of social enterprise organizations navigating challenges (Diochon & Anderson, 2011). Participants discussed their roles in this manner and went beyond to describe a sense of social enterprise savvy and resilience inherent in their work. Elements of social enterprise savvy and resilience as conveyed by participants included accountability to the team, comfort with being uncomfortable, sense of competence to make decisions in the face of ambiguity and/or tension around program vs./and/or business, decentralized decision making, entrepreneur’s mindset, high number of competencies, and manager of multiple stakeholders and relationships simultaneously.

Pivotal Role of Internal Advancement of Program Participants to Full-Time Staff

As workforce development programs and businesses were integrated into participants’ organizations, the talent management issues associated with internal advancement were prominent in interviews. The role of program participants (i.e., also described as trainees, interns, etc.) advancing from social enterprise training programs to full-time staff positions within the organization itself was discussed in most organizations. Key issues included blurring lines between workforce development training and full-time employment staffing, the opportunity, need, and resource dilemma of developing greater human potential, and the time horizon for further professional development.

4. Talent Management Culture

The integration of values from the two cultures inherent in social enterprise: charitable and entrepreneurial culture was the strategy that created social value (Dees, 2012). The importance of culture in unifying employees, and facilitating shared understanding of organizational norms is key for organizational effectiveness and employee satisfaction and engagement. This theme transcended the size of organizations, expressed by participants representing small organizations, as well as by those at large organizations.

There is an attraction to work at an organization that is a mission-based organization. It is attractive because it is personally fulfilling. Once there is a sense of comradery, team within the organization, the people get along with each other, enjoy coming to work. I think it is important to enjoy the people you work with. I did not have that in my previous company. (SE06R02)

We do have some long-term staff that actually have a hard time leaving here because they feel so invested in the culture here and the people that they work with, including former trainees that are our longest tenured employees here. (SE13R01)

Inclusion

Social enterprise organizations focused on community and social inclusion through the creation of employment opportunities for people who needed them the most. Inclusion as a talent management driver for staff working at participant organizations was discussed as it related to fair treatment of all people, at all levels in the workplace. Participant SE03R01 emphasized the importance of all employees having a shared understanding of the systems of oppression. They shared their approach to, and experiences of, promoting understanding, while engaging the entire organization.

…that's 40 hours of very rich curriculum around leadership and trust and systems of oppression and cross-cultural communications. And I said the whole team, everybody's got to do it. And it really brought everybody back to, not only what the [title of program participant position] go through, but that what we stand for, and what our values are, and that they had an experiential kind of…so, I think the more we do that kind of stuff that was better than any conference. (SE03R01)

Informal Norms

Participants discussed informal norms around talent management that reflected organizational culture.

I would say it's more informal sort of absorption. They may be written down but it's not in something that is circulated regularly. I think that it's something that people sort of hear about or learn once they're here and maybe more so in our area which is more external facing. But I think that this is something we think about as we are now beginning to expand beyond [the location] and putting [the organization] training and curriculum into an exportable package, how much of the unsaid folklore and the little things that happen here that make it a really interesting and unique place. And I think that relates to culture as well as the training program, as well as the staff. How well are those institutionalized? Because as we've had new people and onboarding kind of varies I think a little bit from one part of the organization to another, that's something that probably will become more important as [the organization] grows. (SE03R02)

5. Talent Management Practices

Talent management practices that could be considered transactional in nature are discussed in this section. These practices include, but are not limited to, recruitment/selection, performance management, professional development, retention, and succession planning. Those mentioned most frequently include professional development, recruitment, and succession planning, each of which is discussed in this section.

Participants often discussed professional development in relation to resource allocation. No particular model of practice emerged through the interviews. Rather, participants shared their views on the merits and shortcomings of these practices, and approached talent in social enterprise as inclusive versus exclusive.

Compensation Strategy Designed to Attract and Retain Top Talent

Participants expressed concerns about compensation at their organizations and in the social enterprise sector. The participants that discussed compensation generally stated that compensation at their organizations and in the sector, was typically lower than in the private sector industry of their social enterprise business. Competing and retaining top talent presented challenges for many organizations.

Inclusion as Continuous Justice and Growth

By the nature of their mission-based work, participants discussed ways that the social enterprise serves as a platform for continuous justice and growth for workers or those who might work there in the future. A prominent theme is the role and responsibility participants feel for creating employment that can provide individual self-sufficiency through income.

Two of the 15 participants described their particular approach to workforce development. While most social enterprises with workforce development programs hire individuals for time-specific training periods (i.e., ranges were as short as 12 weeks, or as long as one year), two organizations hired individuals who would be considered program participants in other social enterprises, directly into full-time staff positions. These organizations did not have a separate, distinct, time-limited training period, but hired individuals with the full intent of providing training and employment.

We are hiring people and offering them employment and it is not transitional, it is a regular job. It is a perfect fit for what we do. It is different from the transactional employment other social enterprises do. We obviously don’t impact as many people, but I am pleased with our approach and look forward to building the business and employing more people. We try to do everything we can to involve everyone at the same level. We are proud when people come in entry level jobs and move up. (SE06R02)

In discussing how there is no distinction between people and their reasons for joining the organization, participant SE15R01 states, “one of the ways that it's manifest is that you wouldn't walk in and immediately identify who was self-identifying as barriered or who wasn't.” Social and community inclusion was incorporated upfront and directly in recruitment and selection practices.

I do ask three or four questions of each type, when I’m hiring people especially for those positions, when you need technical or subject-matter expertise and you’re going to be working with participants. Because it’s not everybody that can keep a foot in both worlds, and I can’t change people’s world views, but I always ask things like “why would a person become homeless?” and really talk about each person as an individual, so I really do try to hire for that quality, because I can teach a lot of things, but I can’t reconstruct their whole world view. (SE12R02)

Strategic Workforce Planning

Strategic talent management centers on the development of strategic jobs located anywhere in an organization, and identifies as pivotal those positions that drive a company’s strategic competitive position (Cappelli & Keller, 2014). Strategic workforce planning to support strategic jobs incorporates (a) identifying key positions that specifically and uniquely contribute to the organization’s strategic competitive advantage, (b) creating a pipeline of high-potential and high-performing incumbents for these key positions, and (c) building internal systems and processes to recruit and retain individuals for these key positions. Strategic workforce planning was not a central theme in this study. One participant emphasized the importance of this approach for their organization.

Social enterprise people balance movement within their organizations from the program side of the organization to the business side of the organization. I think the biggest thing that we had to overcome, and that social enterprises are faced with…is accessing market-based talent outside of the context of your non-profit. We have to attract them into this unique scenario. But at the same time, that's the right flow versus trying to develop somebody who used to be here and doesn't have that market-based experience. So that, to me, is the biggest dynamic that we've been trying to improve on and work with to be successful. (SE07R01)

Toward a Theory of Talent Management in Social Enterprise

The five themes and subthemes were compared and contrasted to social enterprise and talent management theory presented through this study, as a way to analyze where similar and divergent associations occurred. Through theoretical coding, I reengaged with several research participants (i.e., theoretical sampling) to explore (a) whether there might have been alternative explanations for the research findings, (b) relationships between the themes, (c) confirm whether theoretical saturation had been reached, and (d) ground suppositions and hunches in the data (Charmaz, 2014). Theoretical sampling served as the grounding for constructing a theory for the study.

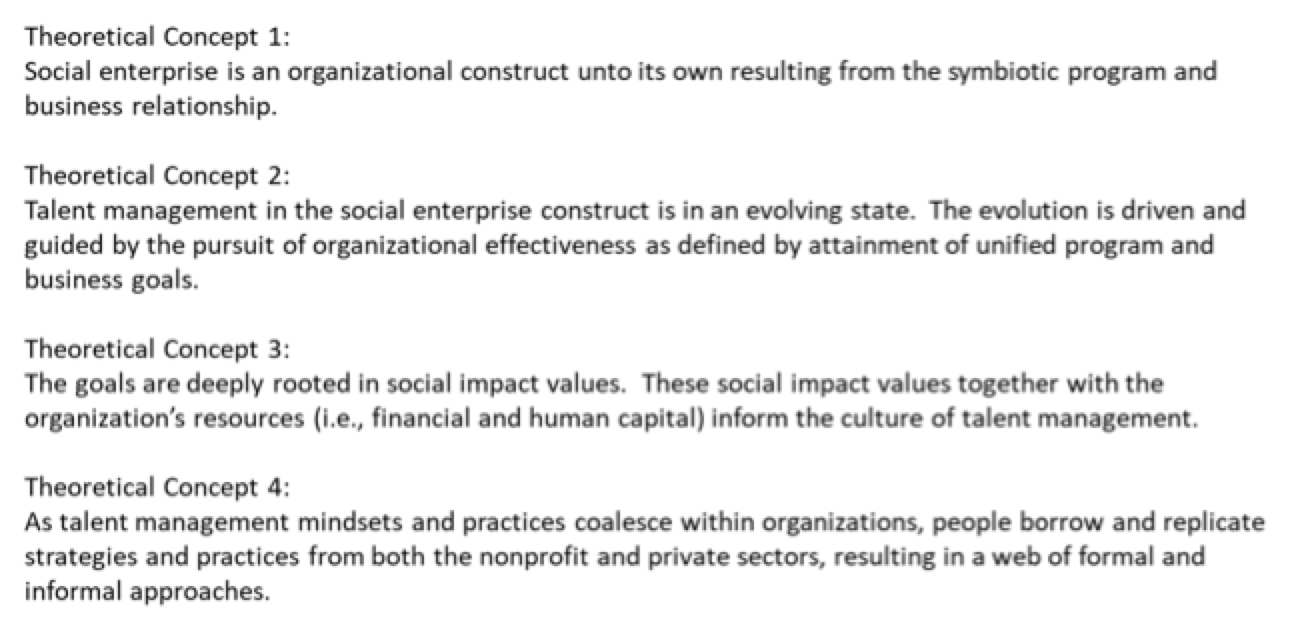

The theory of talent management in social enterprise organizations and a commensurate visual representation are presented in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1. The study’s theory of talent management is presented as a set of theoretical concepts.

Figure 2. Visual representation of the theory of talent management in social enterprise organizations.

Implications for Practice: The Talent Imperative Model for Social Enterprise

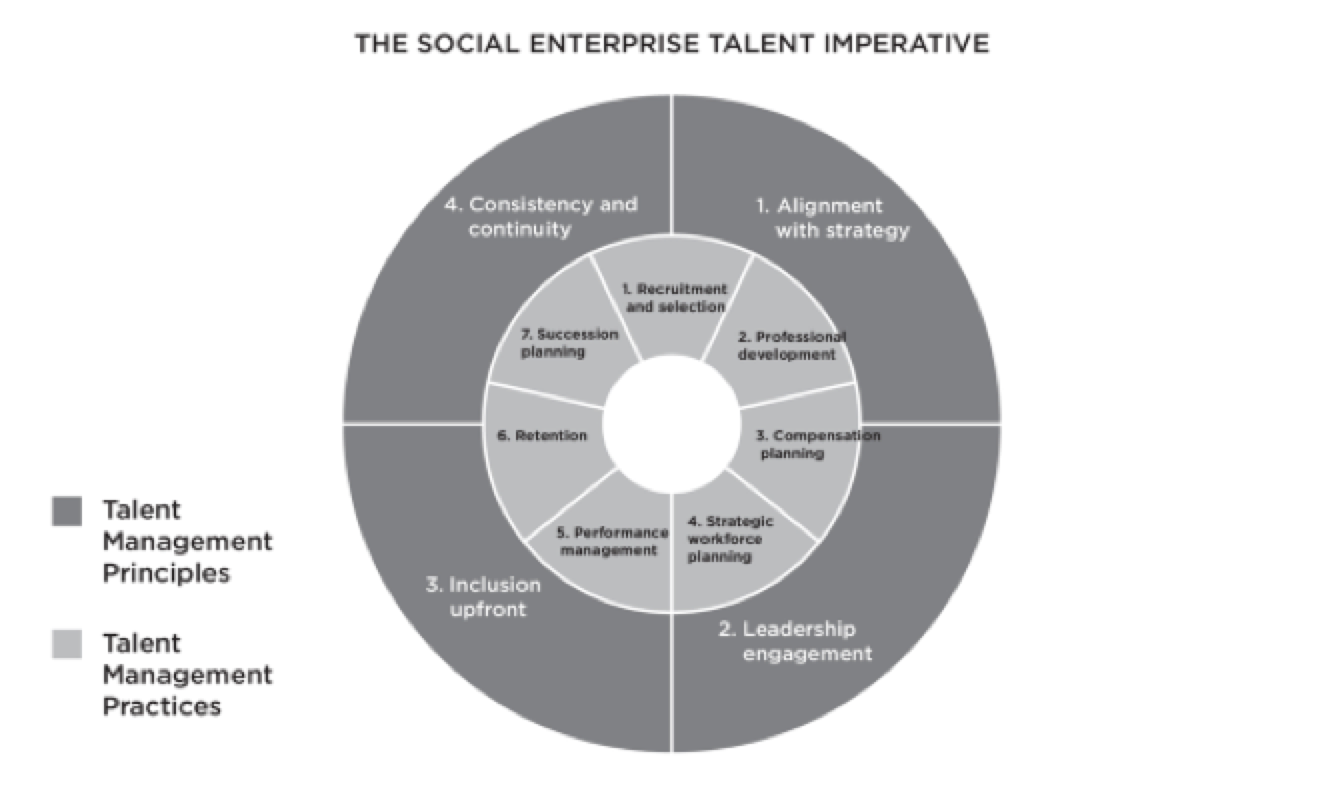

Building on the study findings, the grounded theory of talent management, and scholarly works in talent management and social entrepreneurship, a model of talent management for social enterprise and nonprofit organizations could be applied in practice. The Talent Imperative, presented in Figure 3, distributes the essence of talent management into two central parts: principles and practices.

Figure 3. This figure presents the Talent Imperative, a framework for talent management for practitioners in the social enterprise field building from Stahl et al. (2012)

The Talent Imperative Model further refines the grounded theory of talent management by incorporating principles and practices, which align directly and intentionally with the symbiotic and distinctive nature of the social enterprise organizational construct. The Talent Imperative Model is a framework to design and sustain workplaces that lead with humanness, inclusion, and organizational effectiveness. It includes four principles: alignment with strategy, leadership engagement, inclusion upfront, and consistency and continuity, as well as seven practices: recruitment and selection, professional development, compensation planning, strategic workforce planning, performance management, retention, and succession planning.

Talent Management Principles

- Alignment with strategy positions all people with a connection to the organization’s core, and provides a mechanism for individuals to understand how their contributions connect to goal attainment.

- Leadership engagement places a priority and clarifies how people are regarded at all levels of the organization. Leadership engagement includes the management team and governing board within the context of their respective roles and responsibilities. The goal is positive and authentic engagement with each individual throughout the organization to communicate, fulfill, and reinforce the talent management imperative as the core driver for humanness and inclusion in the workplace and organizational effectiveness.

- Inclusion upfront builds deeper commitment to the essential individual, social, and community-inclusion values that are at the core of the social enterprise ethos.

- Consistency and continuity of talent management approaches and practices secure an organization’s means of operating, to weather changing environments, and to build humanness and trust throughout the organization.

Talent Management Practices

- Recruitment and selection as the entry point and a brand promise for people interested in working in organizations. This should offer an honest picture of the expectations, conditions, and possibilities. The special competencies germane to nonprofit social enterprise organizations with workforce development programs: Industry+ and social enterprise savvy/resilience/true grit can guide recruitment and selection.

- Professional development commitments and resource allocations can be strategically defined as investment strategies for individual and organizational growth, and sustainability aligned with program goals.

- Compensation planning that benchmarks against a hybrid or combination of nonprofit and private sector scenarios offers a realistic and equitable framework for expectations and plans.

- Strategic workforce planning recognizes that certain positions/roles are pivotal for organizational effectiveness. It does not preclude an inclusive approach to talent management. Rather, it secures people in positions that have special meaning or purpose, such as former participants advancing to full-time positions. Planning can bring new thought, energy, and the (re)distribution of resources to support these positions/roles.

- Performance management ensures that people have clarity about their contributions, particularly about the organization’s strategy/strategic plan. Mutual expectations between people and organizations can be demystified in the process.

- Retention practices help people and organizations. These practices help create an environment and culture where people feel a sense a belonging, knowing that their future is important to organizational effectiveness and success. From the organizational standpoint, retention practices are financially wise, as replacing people can incur significant costs.

- Succession planning is important in social enterprise organizations where the nuances of managing and governing, given their symbiotic nature, are particularly complex. Succession planning practices ensure that there is a thoughtful and planned approach for the departures that inevitably occur -- both expected and unexpected.

Accelerating the Talent Imperative

The Talent Imperative Model is a starting point for discovery and exploration on how to accelerate humanness in the workplace, social and community inclusion, and organizational effectiveness. For some, it may simply be an opportunity for discussion and reflection on workplace issues. Others may be ready for a discussion of broader impact and/or immediate planning and action. Here is a succinct three-month plan from to discovery to action to help practitioners get started.

Month 1. Organizing, Discovery

1a. Create a leadership-staff talent imperative committee.

Form an internal guiding team that can help steward thought-leadership and action on the talent imperative in your organization. The ED/CEO should convene the committee and it should have cross-functional representation.

1b. Get curious.

Ground your work in data. Conduct your own internal assessment on the state of talent management within your organization. Convene one or more internal focus groups and/or conduct one-on-one interviews to answer the central question; do we have talent management (a) philosophies, principles, mindsets, and (b) practices? Summarize your findings into key themes.

Month 2. Think-in

2a. Organize a talent management think-in to review findings.

Bring together the guiding committee and a few others that might be helpful. Review the findings from your internal assessment.

Key discovery questions:

- What are the top three to five things you have learned? Why are they important?

- Review the Talent Imperative Model. How does it relate to your findings?

2b. Design your organization’s Talent Imperative Model

Key discovery questions:

- If your organization had a Talent Imperative Model, what would it look like? Why or what is the rationale?

- What positive change can you anticipate in terms of humanness, social, and community inclusion and organizational effectiveness?

Month 2 or 3. Take Action

3. a. Identify three action steps to build and implement a Talent Imperative Model.

Be bold and realistic. Give yourselves six to 12 months to implement. Create a mini-plan (including identification of resources needed) comprised of SMART goals for the action steps. Figure out how to realize measurable progress within each month. Build in accountability with the committee.

3b. Celebrate milestones and progress.

Face barriers and obstacles with honesty and authenticity.

Conclusion

The role of talent management in social enterprise organizations was studied from a broad perspective that facilitated inquiry on conceptual and practical levels. The generosity of spirit shown by research participants who shared their most honest and reflective thoughts, experiences, and perceptions offered an immense contribution to the breadth and depth of this qualitative research study. The findings suggest that, while organizations borrow and replicate talent management strategies, approaches, and practices from the nonprofit and private sectors, there was a demonstrated need for a talent management model to address the symbiotic nature of the program and business dynamics. Study findings provided an opportunity to begin testing a model, the Talent Imperative, in the social enterprise sector and beyond.

Works Cited

Cappelli, Peter, and JR Keller. "Talent Management: Conceptual Approaches and Practical Challenges." Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1, no. 1 (2014): 305-331.

Charmaz, Kathy. Constructing Grounded Theory (2nd ed.). London: SAGE Publications, 2014.

Collings, David G., and Kamel Mellahi. "Strategic Talent Management: A Review and Research Agenda." Human Resource Management Review. 19, no. 4 (2009): 304-313.

Dees, Gregory. "A Tale of Two Cultures: Charity, Problem Solving, and The Future of Social Entrepreneurship." Journal of Business Ethics 111, no. 3 (2012): 321-334.

Diochon, Monica, and Alistar R. Anderson. "Ambivalence and Ambiguity in Social Enterprise; Narratives About Values in Reconciling Purpose and Practices." International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 7, no. 1 (2011): 93-109.

Grieco, Cecilia, Laura Michelini, and Gennaro Iasevoli. "Measuring Value Creation in Social Enterprises: A Cluster Analysis of Social Impact Assessment Models." Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 44, no. 6 (2015): 1173-1193.

Kim, Yeonsoo, Rachele Williams, William J. Rothwell, and Paul Penaloza. "A Strategic Model for Technical Talent Management: A Model Based on a Qualitative Case Study." Performance Improvement Quarterly 26, no. 4 (2014): 93-121.

Ross, Suzanne. "How Definitions of Talent Suppress Talent Management." Industrial and Commercial Training 45, no. 3 (2013): 166-170.

Silzer, Robert and Ben E. Dowell, eds. Strategy-Driven Talent Management: A Leadership Imperative. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2010.

Stahl, Günter K., Ingmar Björkman, Elaine Farndale, Shad S. Morris, Jaap Paauwe, Paul Stiles, Jonathan Trevor and Patrick Wright. "Six Principles of Effective Global Talent Management." MIT Sloan Management Review 53, no. 2 (2012): 25-32.

Tansley, Carol. "What Do We Mean by The Term "Talent" in Talent Management? Industrial and Commercial Training, 43, no. 5, 266-274." (2011):