The following was originally published by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government as part of its Occasional Papers Series.

I. Introduction

In cities across the country, promising efforts to achieve greater efficiency and impact with fewer dollars are beginning to take hold. Today’s fiscal, social and technological context is making innovative governance increasingly important for city officials and the agencies and jurisdictions they lead. Cities are reframing innovation from a value-based concept to a concrete goal with specific targets in the same manner that they have transformed their approach to values such as efficiency and transparency. And, echoing the adage that “what gets measured gets done,” cities are beginning to tackle the challenges of measuring their efforts and results in supporting and promoting innovation. While city leaders can be innovators themselves, they can also help unleash innovation in their communities by connecting and supporting local entrepreneurs, enacting favorable policy changes and mobilizing citizens behind reform. Whether acting directly or enhancing the efforts of others, these leaders are actively working towards the development and sustainability of ongoing innovation in their jurisdictions.

But what might an innovative jurisdiction look like?

Innovative cities are not simply creative. They set the stage for inventiveness and reform by committing attention, time and resources to rethinking local problems and rethinking the instruments (programs, policies, funds and services) they currently deploy to address those problems. They also provide ample opportunity and support for creative improvements and promising new approaches to public problem solving. The rules and administrative procedures for public contracting are flexible and efficient enough for both new entrants and established providers to be competitive. Further, city leaders not only encourage well-informed risk taking from their employees—they also provide the support, training and resources their personnel need to become public innovators.

While this vision may seem an improbable one for government, the authors have found that the strategies above are already being tested and deployed in cities across the country. Communities are working to strengthen the civic, institutional and political building blocks that are critical to developing new solutions to public problems—or what the authors call the local “innovation landscape.” That said, the authors have not found a city or community that is applying what they consider to be a comprehensive approach to creating a more innovative jurisdiction.

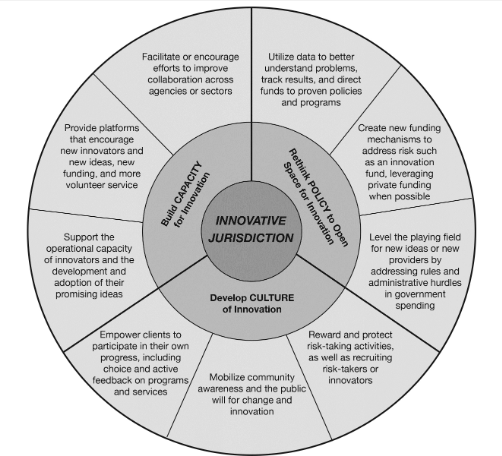

This three-part miniseries explores the local innovation landscape not only through the lens of specific individuals and organizations but also through the lens of delivery systems and networks that include a variety of service providers, funders, constituents, advocates and other stakeholders. The first paper introduces readers to the nature of this work and presents three case studies exploring current efforts to drive innovation in Boston, Denver and New York City. The paper also orients the miniseries within the robust discourse on government innovation. In the second paper, the authors introduce a comprehensive framework to help cities lay the groundwork for identifying, developing and adopting innovative solutions. The authors developed and refined this framework from interviews with dozens of city officials, online forums, first-person accounts, practitioner surveys and fieldwork. The framework comprises these primary strategies: (1) building the city’s capacity to solve challenging public problems; (2) reforming policy making to address administrative, structural and political hurdles to innovation; and (3) creating and maintaining a culture that intentionally seeks out, values and expects creativity and change.

The figure below highlights the main strategies and components of the framework.

This third and final paper of the miniseries focuses on implementation of the framework’s strategies and introduces a unique assessment tool that builds on the foundational research for the framework. Public leaders can use this tool to determine the health of their current efforts to improve their local landscapes for innovation, evaluate their progress and communicate the value of their work to residents and key stakeholders. It is important to note that both the framework and the assessment tool were built on the assumption that innovation as an ongoing endeavor is valuable in its own right, independent of the success or failure of any individual innovation. While the authors focus on innovation as the means to a desirable ends—improvement or modernization of service delivery, operational efficiencies and savings and material changes in quality of life—the assessment tool does not attempt to capture the results or impact of individual innovations. Instead, the assessment tool is intended to measure the degree to which a city is employing a specific set of levers or drivers that they may reasonably expect to result in innovation and change.

This assessment tool differs from traditional performance management systems in that it focuses on the structural conditions that encourage innovation. Although there is increasing research available, the authors have identified few efforts to date to develop common standards, tools or systems related to measuring efforts to support or promote public innovation. The difficulty of agreeing on the value, scope, substance and impact of innovation may pose an obstacle. Similarly, research on public-sector innovation has often sought to understand the actions of individual innovators to overcome common obstacles. Little published work focuses on how public leaders can improve their local landscapes for innovation in solving public problems. The goal of this miniseries is not to offer a definitive statement on the most effective approach to public innovation. It is to make a useful contribution to the active discourse in cities across the country on how to support and promote civic innovation.

With this in mind, the assessment tool identifies a set of actionable objectives in support of each component of the framework, suggests key questions that are relevant for each objective and includes sample indicators that could assist in answering those key questions. To remain grounded in practice, the authors conduct a conceptual test of the framework and assessment tool using the nationally recognized Center for Economic Opportunity (CEO) in New York City. This office, developed by Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration, delivers new solutions for residents living in poverty. This paper concludes by addressing some common considerations of and challenges to implementing strategies to support and promote innovation. These considerations include location and accountability, budget and staffing, personnel rules and unions, the costs of evaluation and sustainability across administrations. Each challenge highlights examples of potential solutions from CEO and other cities interviewed by the authors.

II. Assessment Tool

City officials engaged in efforts to improve their local landscapes for innovation must answer three questions: First, what strategies are we pursuing and how do we know if they are actually working? In order for city officials to know whether their efforts are effective (in terms of both cost and results), they need to utilize an assessment or measurement system. Second, how do we communicate the value of our efforts to the public and other stakeholders—in effect creating broader demand for innovation? Ideally, any leader driving innovation wants to be able to deliver a strong narrative about effectiveness, efficiencies and the promise of long-term results. And, finally, how can we institutionalize our work to ensure that future administrations will sustain those efforts?

The goal of the assessment tool is to help cities develop a sophisticated approach to supporting and promoting innovation by (1) assessing their current efforts through the lens of the framework’s strategies, (2) adapting the framework to their local contexts and communities and (3) capturing metrics in a manner that responds to the three questions above.

Concepts and Definitions

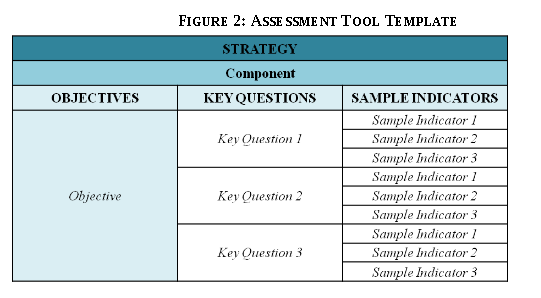

The assessment tool reflects the framework introduced in the second paper of this miniseries, which comprises three main strategies, each of which has three components (see Figure 1 above). The tool identifies actionable objectives in support of each component of the framework, suggests key questions relevant for each objective, and includes sample indicators to address those key questions. The tool is designed as a series of charts, with one for each of the nine components of the framework. The full series of charts included with this paper follows the format below.

Here, the authors further define the core concepts utilized in the assessment tool.

Innovation: The assessment tool refers to innovation in two ways: First, innovation can be viewed as ideas—translated into programs, policies or operational improvements—that are novel or unique to the adopting institution or city. Second, innovation can also be viewed as a process rather than a product (Andrea Coleman, personal communication, June 12, 2013). The process of innovation might include—but is not limited to—initial prompting or identification of an idea, development and testing, refinement, replication or scaling (across programs/agencies, across delivery systems or to outside jurisdictions) and durability—the quality of being able to withstand the passing of time and changes in administration.

Actors: The assessment tool is designed from the perspective of those whose portfolios include responsibility for driving innovation. The primary actors cited include:

- Mayor’s Office: Scope of work includes policy and oversight of most agencies across city government.

- Agency: Scope of work includes a specific portfolio such as health and human services or housing and community development, including oversight of external contractors and vendors.

- Innovation Office: Scope of work includes an innovation-specific portfolio (this office may be housed within the mayor’s office or within an agency or may exist as a stand-alone agency).

Objectives: For each component in the framework, the assessment suggests a set of desired objectives to guide the actor’s innovation efforts, taking into consideration any number of factors, including mayoral priorities, political feasibility, operational capacity, etc. The authors encourage actors to consider or identify alternate objectives more relevant to their local contexts.

Key Questions: For each objective, the assessment tool presents a set of key questions to help actors evaluate whether and to what degree they are meeting stated objectives. (Another way to look at key questions is, “How will we know if this goal is being achieved?” See Building a Government Balanced Scorecard: Phase 1 – Planning by Paul Arveson, The Balanced Scorecard Institute, March 2003.) As with the objectives, the authors envision cities choosing from among these key questions (and identifying others) based on local priorities and capacity.

Sample Indicators: For each question, the assessment tool provides sample indicators that a city can employ to form an answer. The authors include these indicators as suggestions, recognizing that each city is unique in terms of not only its priorities but also the availability of data and other resources. The most basic criterion for an effective indicator is that it provides a direct answer (or reasonably effective proxy) to its key question. Further, the indicators a city chooses should be measurable within a relatively short timeframe (i.e., one or two years maximum), and data gathering and analysis for indicators must not be cost-prohibitive. When selecting indicators, the method and means for collecting the data are important considerations. Existing sources of data are ideal, but in some cases, data will have to be collected through such mechanisms as interviews, surveys and a review of available public or internal documents. In addition to numerical data or values, actors may also want to include qualitative descriptions to help them compare specific efforts year over year and develop a persuasive narrative that communicates the value of the work.

Deploying the Assessment Tool

The assessment tool is designed to help cities identify their priorities and assess their progress in developing more innovative jurisdictions. Rather than answer every question in the assessment, the authors suggest that cities utilize this tool to help them identify or adapt the most relevant and feasible components, objectives, questions and indicators based on competing priorities, political and operational feasibility and other local considerations. While some cities might choose to utilize a version of the assessment tool as a rating or grading mechanism—incorporated into an existing performance dashboard, for example—the authors believe the tool’s primary value is to facilitate discussion, refinement and further development of local innovation landscape efforts. Publishing results from the assessment tool internally or publicly might also prove useful to local innovation offices and teams. In addition to building coalitions, communicating the value of innovation efforts can be critical to mobilizing constituents behind these efforts.

|

“Different purposes require different measures. Knowing what to measure begins with knowing what you want to measure.” —Robert Behn, Harvard Kennedy School (2003, p.) The best-known examples of local performance management systems are CitiStat, developed in Baltimore, and its inspiration, the New York City Police Department’s CompStat system. Scholars such as Robert Behn have identified useful implementation tips as relevant to this assessment tool as they are to public managers who use a performance management system as a leadership strategy—what Behn considers to be its ultimate purpose (2012, p. 56). Based on his extensive study of “PerformanceStat” systems, Behn suggests that the most effective officials follow steps such as conducting a baseline assessment, identifying targets and assembling personnel and resources to follow up on feedback from the assessment. Building on the work of Behn and others, the authors propose six key steps in deploying the assessment tool:

|

Because most city agencies are familiar with if not already implementing some type of performance measurement system, the authors anticipate that cities might either incorporate the key objectives, questions and indicators from the assessment tool into their existing performance systems orimplement the tool (or portions of it) as a stand-alone system. No matter the approach, pulling data from as many sources as available is important because the questions touch on many issues from across a city (Government Technology, 2012). For example, NYC’s Center for Economic Opportunity collects and consolidates data each quarter from multiple partner agencies. While some of these data are new, much has already been recorded and reported by the agencies themselves, whether out of obligation to outside funders or through their monitoring of contracted providers (Carson Hicks, personal communication, November 27, 2012). In addition to leveraging existing data and sources, CEO also contracts with respected outside evaluators to help survey and measure the effectiveness of both pilot programs and CEO itself. CEO’s work is discussed further in the case study below.

III. Conceptual Test: New York City’s Center for Economic Opportunity

To help evaluate the validity and comprehensiveness of the framework and assessment tool set forth in this miniseries, it is useful to engage in a conceptual test that compares the authors’ ideas with a real-world effort that holds promoting and supporting innovation at the core of its mission, planning and everyday work. As one of the more advanced local efforts identified by the authors, New York City’s Center for Economic Opportunity serves as a useful model. CEO’s strategies and methods of implementation allowed the authors to evaluate the content and feasibility of both the framework and the assessment tool. Following the test results, the authors discuss common considerations and challenges that arise when implementing efforts to support and promote innovation and include examples of solutions from CEO and a handful of other cities that are pursuing local innovation strategies.

Background

In 2006, a cross-sector commission appointed by New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg devised a novel approach to identifying, funding and evaluating solutions that would help lift families and individuals out of poverty. The mayor embraced the commission’s idea, established it as CEO and structured it as part of the Mayor’s Office—signaling that the new entity was a Bloomberg priority. CEO quickly hired a nontraditional team (people from outside of government), developed an active network of city agencies, local providers and external evaluators and identified innovative efforts (defined as “developing new program models or adopting evidence-based programs”) to support, pilot and evaluate (Metis Associates, 2009, p. 28).

Currently, approximately half of CEO’s time and resources are invested in finding solutions for disconnected youth, with an emphasis on innovations in education, skill building and accessing job opportunities. Other priorities include asset building and career development for the city’s working poor. CEO provides a mix of public and private dollars to city agencies that in turn fund government and nonprofit service providers. Each idea is implemented with rigorous evaluation and regular refinement and improvement. At the end of the pilot phase for a new idea (generally three to five years), CEO and the partner agency decide whether to continue, expand or terminate funding for the model.

Since its inception, CEO has maintained strong backing from the mayor, as well as from a range of prominent philanthropic foundations, business leaders and community groups. For its part, CEO has sought to be an effective partner to city agencies, a champion for rigorous and transparent monitoring and evaluation and a policy advocate for anti-poverty efforts. To date, CEO has piloted close to 70 programs and policy initiatives in the areas of asset development, employment and training and education. Of these, eight programs have been deemed successful in helping to reduce poverty by external evaluations, including: CUNY ASAP, Earned Income Tax Credit mailings, Jobs-Plus, Office of Food Policy Coordinator, and CEO’s initiative to redefine the way poverty is measured. A slightly greater number of programs have been discontinued, while most are still in the pilot phase as of publication.

In recognition of its work, CEO received three $5.7 million grants from the White House Social Innovation Fund in 2010, 2011 and 2012 to adapt five of its most promising programs in a handful of other cities. In 2012, CEO was also selected from among nearly 600 government programs as the winner of the Innovations in American Government Award, administered by the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at the Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government. Notably, CEO is both an innovation itself and an effort to promote and support innovation across a jurisdiction. Beyond the identification and piloting of individual solutions, CEO works to improve the landscape for innovation within which cityagencies and local service providers support those living in poverty. Central to this work are the collection and real-time utilization of performance data on the programs in CEO’s portfolio. This focus on evidence serves multiple functions for CEO, helping staff and leadership build on the available knowledge base, experiment with new models and cut programs that are not delivering results.

Testing the Framework and Assessment

In this section, the authors describe CEO’s efforts as they relate to the framework’s nine components and the assessment tool’s suggested objectives for each component. They summarize how and to what extent CEO works towards these objectives and also briefly highlight how CEO currently measures its own work.

Strategy I: Build Capacity for Innovation. CEO provides a robust example of the framework’s first strategy, the components of which include improving collaboration across agencies or sectors, creating platforms for new ideas and innovators and developing innovators and their promising ideas. Indeed, a 2009 evaluation conducted by Metis Associates of CEO’s impact on city partner agencies, nonprofit providers and broader social service delivery systems corroborates this assessment. It found that the high satisfaction with CEO among city agencies and service providers was based on CEO pushing them to rethink their programs, create the space to test new models, build capacity for evaluation and documentation and share lessons learned (Metis Associates, 2009).

Component I.A.—Facilitate or Encourage Efforts to Improve Collaboration across Agencies or Sectors

Cities can build their collective capacities for innovation by working to improve collaboration among existing efforts. The authors suggest that this component includes three core objectives:

- Objective I.A.1. Lay the groundwork for more effective partnering and collaboration. The relationship between CEO and city partner agencies, according to Director of Programs and Evaluation Carson Hicks, is an equal partnership in the sense that both entities provide a distinct set of skills and knowledge. CEO program managers are assigned portfolios in specific issue areas and meet with relevant agency personnel and nonprofit providers as regularly as every two weeks. By sharing performance data, conducting site visits and speaking with participants, CEO and agency staff work together to make adjustments and refine programs in real time.

- Objective I.A.2. Increase the number of formal collaborations. Of the three objectives for improving collaboration, CEO has been shown to be particularly effective at both increasing the number of collaborative networks in which it engages and leveraging these networks. CEO’s network has extended to roughly 30 city agencies over the last seven years, always with the primary goals of finding new ideas, designing and implementing pilot programs and collecting and analyzing performance data. When CEO won the 2012 Innovations in American Government Award, Ash Center Director Tony Saich noted, “Not only is the Center for Economic Opportunity innovative, it demonstrates a sea change in how a city can unite the disparate interests of previously siloed agencies, funders, providers, and businesses to tackle poverty, one of our nation’s major growing challenges” (Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, 2012).

- Objective I.A.3. Leverage collaborative networks to identify and disseminate new models. Through in-depth interviews with personnel from street-level providers to senior staff in the mayor’s office, outside evaluators reported increased collaboration between agencies —and the subsequent exchange of new ideas—as CEO’s most notable system-level impact (Metis Associates, 2009). CEO and its partner agencies, for example, convene nonprofit providers on a regular basis to surface program-related issues and share lessons across providers. On an individual level, CEO program managers are expected to be well versed in the policy field over which they have responsibility—such as workforce development, asset building or disconnected youth. This includes having familiarity with key players both locally and nationally. According to Hicks, program managers leverage these networks to promote CEO’s work and to connect colleagues at partner agencies and nonprofit providers to experts and potential donors, helping facilitate the flow of knowledge within specific policy areas as well as sharing functional skills such as evaluation and retention that are relevant to anyone working at innovation.

In terms of measuring its effectiveness in improving collaboration, CEO is still working on how best to capture evidence that demonstrates the impact of its efforts. Hicks notes that CEO tries to determine how its presence affects agency operations and practices by observing, for example, whether “practices [are] more effective as a result of partnering with CEO, or extending things that they and initiatives that they piloted with CEO to other areas of their agency. We think that’s a measure of success” (Hicks, November 27, 2012). While CEO does report on the number of agencies it collaborates with, and on the better coordination between agencies that it helps to facilitate, there is not yet any concrete set of metrics for assessing CEO’s overall performance in facilitating collaboration.

Component I.B.—Provide Platforms that Encourage New Innovators and New Ideas, New Funding, and More Volunteer Service

Cities can also build their collective capacities for innovation by creating or supporting new mechanisms to attract innovators, ideas and resources. The authors suggest that this component comprises four key objectives:

- Objective I.B.1. Host or support platforms to attract new innovators. The CEO team itself acts as a particularly strong, albeit informal, platform for attracting innovators and their ideas. To help bring new innovators into the public system, CEO and its partner agencies are required to follow the same Public Procurement Board rules as all city agencies, including issuing a concept paper outlining the problem to be addressed—and perhaps hosting a bidders’ conference—to solicit feedback and inquiries from potential service providers that are new to the city.

- Objective I.B.2. Host or support platforms to attract new ideas. CEO also acts as an effective platform for attracting new ideas. Indeed, Hicks estimates that approximately half of the ideas in CEO’s pipeline are imported from elsewhere. Even those ideas that are generated internally tend to be copied from—or inspired by—work that is already happening elsewhere. Recently, CEO decided to look closer to home and invited local nonprofit providers to submit proposals featuring their most innovative anti-poverty solutions. According to Hicks, CEO’s NYC Innovative Nonprofit Awards competition, which received over 50 applications during its inaugural year in 2013, is intended to “identify what innovation is happening in the city that we didn’t know about” (Carson Hicks, personal communication, June 13, 2013). The selection criteria mirrored CEO’s approach to its own innovation fund: “data collection and rigorous evaluation” (City of New York, 2013).

- Objective I.B.3. Host or support platforms to attract private funding. CEO has a strong track record in attracting private funding. For example, in seven years, CEO raised $127 million in private funds to bolster its $530 million in local, state and federal dollars (Carson Hicks, personal communication, September 13, 2013). CEO uses these private dollars to help mitigate the risks of new ideas because private funds do not face the same restrictions as do public dollars.

- Objective I.B.4. Host or support platforms to attract volunteer service.

Although this objective is not a current priority for CEO, the Mayor’s Office runs another initiative, NYC Service, with the express purpose of recruiting volunteers and directing their efforts toward the greatest impact. The program, launched in 2009, has coordinated the volunteer activities of over two million residents (NYC Service, 2012). In a case such as this, where the innovation team is not directly responsible for a key objective, the team might approach the relevant program or agency for cooperation in completing the assessment.

In terms of measuring its effectiveness in creating platforms that attract new innovators and their ideas, CEO measures limited aspects of its innovation pipeline. According to Hicks, the inflow of new ideas is so constant and so embedded in the culture of CEO that the office does not track ideas until they move into the pilot phase—which usually includes more than 40 pilots at any given time (Carson Hicks, personal communication, December 12, 2012.).

Component I.C.—Support the Operational Capacity of Innovators and the Development and Adoption of Their Promising Ideas

Finally, cities can also build their collective capacity for innovation by helping to develop innovative organizations and helping the most promising innovations to move toward adoption and scale. The authors suggest that this component comprises the following three objectives:

- Objective I.C.1. Support the operational capacity of innovators with key skills training, networking and other resources. CEO works closely with their partner agencies to develop ideas into pilot programs. For example, CEO connects agencies to those with expertise in various aspects of the innovation process. Similarly, CEO recently created a professional development course for nonprofit program directors with City University of New York that teaches management, data collection and other skills. CEO staff members also speak regularly on the lessons they have learned related to data collection, evaluation and program management at local conferences.

- Objective I.C.2. Establish systems and supports to develop, test and refine the most promising ideas. Once a new idea is in CEO’s pipeline, the office examines it to determine its feasibility. Considerations include level of interest among senior leadership at CEO, potential partner agencies, likely availability of funding sources, potential for scale and anticipated political will (Carson Hicks, personal communication, December 17, 2012). If an idea passes this initial filter, CEO approaches a partner agency to gauge their interest in piloting it. In addition to funding support, CEO offers partner agencies and nonprofit providers operational support, including technical expertise and additional personnel (generally two to four staff people per agency). CEO also offers agencies funding for fiscal and contract departments and for new or more robust data collection systems (Carson Hicks, personal communication, June 13, 2013).

- Objective I.C.3. Aid in the adoption or incorporation of innovations with proven impact. CEO works closely with partner agencies on evaluation; those programs shown to be effective are adopted by partner agencies and graduated out of CEO. CEO also won a White House Social Innovation Fund award to replicate its most effective program models in other cities.

CEO’s ability to develop promising innovations was captured in a report it published in which Metis Associates surveyed CEO’s partner agencies and determined that the agencies were incorporating lessons from CEO or CEO-funded programs into their operations as well as making improvements in their abilities to innovate or experiment with new approaches. The same report found that CEO’s initiatives to support operational capacity building within partner agencies had led to an increase in their effectiveness at serving clients (Metis Associates, 2009). In tracking the progress of its pilot programs, CEO focuses on the programs’ impacts as well as the host agencies’ commitments to funding the new efforts and their success in integrating the pilots into their work. For example, CEO monitors a program’s ability to raise new funds to expand. CEO also tracks the number of its successful pilot programs that are replicated elsewhere and the number of cities in which they are replicated (Center for Economic Opportunity, 2010).

Strategy II: Rethink Policy to Open Space for Innovation.

CEO also provides a strong example of the framework’s second strategy of focusing on policies and regulations. CEO places significant emphasis on this strategy and provides useful examples of its three core components, utilizing data, securing risk capital and eliminating barriers to innovation.

Component II.A.—Utilize Data to Better Understand Problems, Track Results, and Direct Funds to Proven Policies and Programs

Cities can work to refine their policy landscapes and open space for innovation by improving their ability to deploy data in meaningful ways. The authors suggest that this component comprises the following five key objectives:

- Objective II.A.1. Establish a performance measurement system that quantifies outputs and outcomes. After an idea reaches CEO’s pilot phase, participating agencies and their contractors are required to document and report monthly or quarterly on client outcomes and other performance measures, often based on administrative data and results from focus groups. The metrics for these specific programs are developed with the partner agencies, frequently incorporating best practices in the field. Once a pilot program has been running for at least two years, CEO provides funds for an outside evaluator to conduct an impact evaluation (Carson Hicks, personal communication, November 27, 2012).

- Objective II.A.2. Use data and tools to understand problems, prompt insights, make decisions and design solutions. Even before reaching the pilot phase, CEO relies heavily on an existing evidence base—such as program evaluations and research studies—to identify and assess potential outside innovations to consider for its portfolio (Carson Hicks, personal communication, November 27, 2012).

- Objective II.A.3. Align data and evaluation tools to strategic goals. CEO encourages and supports agencies in their efforts to collect real-time performance data and use them in their own decision making. This includes using evaluation data to spot problems and refine program models throughout the pilot phase (Carson Hicks, personal communication, November 27, 2012).

- Objective II.A.4. Use performance data to hold programs or providers accountable for results. If a model is proven to be effective, CEO transfers funding and control of the program to the partner agency (Carson Hicks, personal communication, November 27, 2012). Pilot programs that do not succeed are dropped from the portfolio. In May 2013, CEO announced that it would defund three pilot programs—CUNY PREP, Nursing Career Ladders, and Youth Financial Empowerment—as well as three program replication sites supported by its Social Innovation Fund grant (City of New York, 2013).

- Objective II.A.5. Make data transparent and accessible. CEO reports on the number of partner agencies or programs that are focused on performance data and outcome measurement or that have a performance measurement system in place. Further, CEO’s efforts to redefine the poverty level in New York City and beyond pull data from numerous sources, and CEO is starting to make some of that data easily accessible online (http://www.nyc.gov/html/ceo/html/poverty/lookup.shtml).

Beyond these steps, though, CEO does not currently measure its efforts or its influence—such as “whether they are paying more attention to data or making data-driven decisions”—on the data-specific practices of partner agencies (Carson Hicks, personal communication, November 27, 2012).

Component II.B.—Create Funding Mechanisms to Address Risk Such As an Innovation Fund, Leveraging Private Funding When Possible

Cities can also help refine their policy landscapes and open space for innovation by identifying, designating or creating a small pool of risk capital. Such funds can be critical sources for pursuing innovative strategies in a more unencumbered manner than traditional public funding allows for. The authors suggest that this component comprises three key objectives:

- Objective II.B.1. Establish R & D fund that allows for creation, implementation, and evaluation of innovations. CEO itself acts like a research and development fund that also helps to design, test, deliver and refine innovative program models. CEO’s public-private innovation fund is a key element to its management of risk. Although CEO’s budget is primarily funded by public dollars, the private funding that it receives helps mitigate the political risk of certain programs. A select few programs in the portfolio are fully funded by private dollars because they are of an untested and potentially controversial nature, such as Opportunity NYC, the city’s version of a conditional cash transfer program that ran from 2007 to 2012.

- Objective II.B.2. Establish measures to continue or scale innovations that show success and to discontinue innovations that do not. CEO believes that every idea in an R&D fund is not supposed to succeed. As Hicks notes, “there’s room to fail, but we learn from those failures.” As to decisions on program continuance and scaling, CEO is clear with partner agencies that their funding continues only if the program is working (Carson Hicks, personal communication, November 27, 2012). Program “graduation” out of CEO’s pilot portfolio is based on evidence of success—either through a random assignment evaluation or other analysis that shows impact. If evaluation shows no or little evidence of impact, alternatively, funding is terminated. For CEO, graduation also requires evidence of full adoption of the program by the partner agency, including both incorporating the program into its ongoing operations and dedicating new funding in addition to the funding provided by CEO (Center for Economic Opportunity, 2011).

- Objective II.B.3. Track the number of innovations that are continued, scaled, or discontinued. In addition to tracking and reporting on the total number of initiatives within its portfolio, CEO reports on the number of programs at each stage of the portfolio beginning with piloting, then graduation, and (when applicable) replication or system change.

CEO makes measurement a core function of its innovation fund. In addition to evaluating its individual programs, CEO reports that it evaluates aggregate data about its innovation pipeline, such as tracking the number of pilot programs in operation, the number of programs and agencies focused on outcomes and quality data, the number of successful programs that attain funding from outside CEO, the number of programs that maintain agency funding and the number that are discontinued.

Component II.C.—Level Playing Field for New Ideas and Providers by Addressing Rules and Administrative Hurdles in Spending

Cities can also refine their policy landscapes and diminish barriers to innovation by rethinking the rules, requirements and other administrative hurdles involved in government spending. The authors suggest that this component comprises three key objectives:

- Objective II.C.1. Remove barriers for new providers or new program models. CEO represents an effort to work around barriers (through such practices as collaboration, flexible funding, technical assistance and other supports) rather than remove them. Because CEO’s public-dollar source is a city tax levy, the office has some flexibility in how it spends its funds. In contrast, the relationship between CEO’s partner agencies and the service providers with whom they contract to pilot programs is more often governed by the traditionally complex and prescriptive procurement rules and protocols of New York City. In response, CEO’s staff often helps write RFPs with partner agencies and participates in the review and selection of providers (Carson Hicks, personal communication, December 13, 2012). In an attempt to expedite the entire process, CEO staff communicates regularly with the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services, which oversees all city purchasing. CEO also shares any lessons learned across partner agencies. As with NYC Service, procurement reform is happening but not under the direction or authority of CEO. Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services Linda Gibbs, who oversees CEO, has launched a major initiative to make the process of city purchasing of social services (over $4 billion in annual spending) more efficient on behalf of providers and city agencies. (For more, see http://www.innovations.harvard.edu/xchat-transcript.html?chid=349 or visit the Accelerator online at http://www.nyc.gov/html/hhsaccelerator/html/home/home.shtml.)

- Objective II.C.2. Increase transparency to enlarge the competitor pool for potential providers. CEO and its partner agencies periodically issue concept papers and deploy other methods to make potential service providers aware of new program offerings and to solicit their feedback.

- Objective II.C.3. Fund new programs or new providers through existing sources. Implicit in CEO’s mandate is that its funding goes towards new programs. While most RFPs for public dollars can end up being quite prescriptive in terms of their information requests from providers—and tend to be activity-based rather than outcome-based—the programs in CEO’s portfolio do end up with some flexibility, according to Hicks. Some RFPs are less rigid, such as those that include only fundamental parameters and a per-client cost, and thus can attract new providers or support new programs. Additionally, service providers work with the city agencies and CEO to continuously refine their models during the pilot phases.

The authors did not discover any efforts by CEO to measure its effectiveness in eliminating barriers to innovation by rethinking rules, requirements and other administrative hurdles involved in spending government dollars. The authors suggest that CEO might elect to incorporate measures of other efforts to eliminate these barriers, such as the purchasing reform implemented by Deputy Mayor Gibbs.

Strategy III: Develop Culture of Innovation.

The third framework strategy underscores the importance of developing a culture that protects and rewards risk taking, works to mobilize public will behind significant changes and empowers clients to participate in their own progress. CEO provides some noteworthy examples of activities in support of a more innovative culture.

Component III.A.—Reward and Protect Risk-Taking Activities, as well as Recruiting Risk-Takers or Innovators

Cities can work towards developing a culture of innovation by protecting and rewarding risk taking by individuals with innovative ideas that challenge established practices. The authors suggest that this component comprises four main objectives:

- Objective III.A.1. Encourage and promote innovation and considered risk-taking. Throughout his tenure, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has been explicit in his efforts to change the culture within city government to one that “eagerly tries bold ideas even at the risk of failure” (Ash Center, 2012). CEO is an important and high-profile example of this effort. Indeed, Hicks credits the mayor’s support and CEO’s mandate to experiment and sometimes fail with allowing them to worry less about the typical political risks of innovating (personal communication, November 27, 2012).

- Objective III.A.2. Formalize innovation work within city government. CEO is a recognized innovation office, established by Executive Order No.117, located (organizationally) within the Mayor’s Office (Center for Economic Opportunity, 2011). Geographically speaking, CEO is located just across the street from City Hall. Its proximity to the mayor and to the deputy mayor for health and human services, Linda Gibbs, who oversees CEO, also raises its profile within city government.

- Objective III.A.3. Reward efforts at innovation and risk-taking; protect those who take considered risks. CEO has established itself as a safe place for staff at partner agencies to come with an idea. The office has created a forum for agency staff to discuss relevant topics like innovation, evaluation and poverty. Hicks calls it “carving out a space for agency partners to think about innovation.” Further, while CEO makes it clear that they will terminate funding to programs that fail, it protects the agencies and providers involved from political fallout. CEO does not publicly name shortcomings of partner agencies or nonprofit providers, for example, nor does it identify them as the cause of a pilot program’s failure. Instead, as Hicks explains, CEO’s messaging approach is, “it was just a program model that didn’t work out.” Their reasoning is that building trust and credibility is in everyone’s best interest: “So much of what we do is coordination and working with other agency partners. It is antithetical to those relationships to blame an agency publicly or blast the provider. We would have a lot of difficulties in getting our work done” (personal communication, December 17, 2012).

- Objective III.A.4. Increase potential for innovation through recruiting and human resources strategy. Beyond leadership, another common tactic to foster innovation and risk taking is to hire from across fields or disciplines. According to Hicks, CEO has done just that. Its staff members represent fields and areas of expertise ranging from management consulting to academia; very few come to CEO from government.

In terms of measuring its effectiveness at rewarding or protecting risk taking, while the four objectives above are all central to its approach, CEO does not currently measure its efforts or results.

Component III.B.—Mobilize Community Awareness and the Public Will for Change and Innovation

Cities can also work to develop a culture of innovation by building public demand for innovation or reform. This component highlights the importance of communication and persuasion, and the authors suggest that this component comprises three key objectives:

- Objective III.B.1. Inform the public on major innovation or reform initiatives. CEO’s leadership is constantly aware of and sensitive to the political environment in which it operates and of the importance of educating and informing stakeholders and the broader public about its work. It regularly shares information on its results through the publication of annual and evaluation reports and hosts public discussions or briefings on the release of new reports. Recently it has turned to social media, creating new accounts on Twitter and Facebook for example in early 2013.

- Objective III.B.2. Engage the public in major innovation or reform initiatives. While CEO has focused on developing relationships with the provider community and political stakeholders, most recently through its NYC Innovative Nonprofits Award, it has limited its focus to date on increasing CEO’s profile among the public or the clients its programs serve. As Hicks acknowledges, “we want people to get involved in our programs but we haven’t necessarily put effort behind getting ourselves out there and known as an innovator within city government to the public at large in New York City” (Carson Hicks, personal communication, December 17, 2012).

- Objective III.B.3. Anticipate and plan for opposition to major innovation or reform initiatives. Two concerns that CEO has faced from the city council and others are whether the social service funding it utilizes would be more effective spent directly on residents and whether CEO’s limited funding ($106.5 million in public and private dollars in FY 2013 (Carson Hicks, personal communication, September 13, 2013) out of an annual city budget close to $51 billion [City of New York Office of Management and Budget (OMB), 2013]) is enough to make significant change across the city. In response, CEO has sought to be transparent about the outcome and performance data generated by its programs.

CEO currently tracks its communication with partners, clients and other stakeholders and reports on measures such as the number of reports, working papers and evaluations it has published (Center for Economic Opportunity, 2011). Although all of this material is publicly available upon request, CEO notes that its communication efforts to date have not been focused on educating and mobilizing the general public in support of its work.

Component III.C.—Empower Clients to Participate in Their Own Progress, Including Choice and Feedback on Programs and Services

Finally, cities can work towards developing a culture of innovation by empowering citizens and clients through mechanisms such as self-reporting and feedback tools and by offering choices in service providers. The authors suggest that this component comprises three objectives:

- Objective III.C.1. Measure data at the individual or household level. The common purpose across CEO programs is to help low-income New Yorkers rise above poverty through such steps as accessing education, earning new credentials and raising income savings. CEO programs are distinct from many traditional safety net programs or entitlements in that CEO emphasizes the value of increased expectations for individual potential and responsibility. As such, CEO programs seek concrete investments of time and effort by participants.

- Objective III.C.2. Solicit feedback from citizens (‘clients’ and others) on public services. In addition to its empowering program models, CEO incorporates client perspectives into program development. CEO encourages its service providers—those closest to clients— to measure participant satisfaction and solicit their feedback on programs. CEO also provides direct opportunities for feedback as it implements, evaluates and refines program models in the early pilot phase. For example, CEO staff evaluators regularly conduct client focus groups and participant interviews. In partnership with the Department of Small Business Services, CEO also piloted an online platform where clients could rate their experience with workforce training programs. One challenge Hicks observes is that participants can be hesitant to offer criticism or feedback on the shortcomings of a program with the funder or a representative of City Hall present.

- Objective III.C.3. Promote choice in public services. This objective is not a priority for CEO. While the training program guide highlighted above was intended to improve service delivery, implicit in its design is that future clients would use the feedback to make decisions on which training program to join.

In terms of measurement of these objectives, the authors did not identify examples where CEO was evaluating its efforts to empower clients. In the next and final section, the authors use the experiences of CEO and other cities they have studied to explore common concerns in implementing the framework and the assessment tool and to highlight possible approaches to these considerations and challenges.

IV. Considerations and Challenges to Implementation

Cities must be prepared to face difficult choices and challenges when implementing efforts to support and promote innovation. While many of these will be specific to the local jurisdiction, the authors highlight below some of the more common considerations and challenges uncovered in their research.

Location and Accountability. While it is certainly not a sole determinant for success or failure, the location of an innovation initiative or team within a city’s structure can be an important factor in determining its influence and effectiveness. At CEO, for example, physical and organizational proximity to the mayor’s office increases its authority with other city agencies. It also allows CEO to keep the pulse of the administration’s priorities. Two additional benefits are increased flexibility in the use of city funds and ensuring a clear understanding of CEO’s activities at the highest levels of the administration (Metis Associates, 2009).

Interesting contrasts to CEO’s approach can be seen in Memphis and Phoenix. The city of Memphis observed that proximity to the mayor’s office can also have drawbacks. The pressures to achieve quick successes and the competition from constantly changing priorities within a mayor’s office can divert a centrally located innovation team from its core mission. At the same time, being situated in an agency can provide some distance that might allow for better focus on longer-term, process-oriented efforts. As Kerry Hayes, former Special Assistant for Research and Innovation to Memphis Mayor A.C. Wharton, described, “While working for the government at any level, but particularly in the mayor’s office, for every innovative idea that I want to follow up on, I have five constituent service requests to address” (personal communication, May 25, 2012).

Demonstrating an alternative to centralizing innovation efforts in a specific office or agency, Phoenix’s city manager, David Cavazos, pushed innovation to the frontlines, in part by incorporating it into the annual departmental review process. Evaluation criteria for each of the roughly 20 city departments include efforts toward pursuing innovation, improving customer service and increasing efficiency. Cavazos reports that results from the first two review cycles led to almost $10 million in savings (personal communication, June 18, 2012).

In addition to the location of the innovation office or initiative, accountability is another essential consideration. Cities need to clearly establish to whom innovation teams or offices are accountable for how they spend their time, funds and political capital. One critical challenge is creating an accountability framework that is flexible enough to allow for the iteration of program models and delivery methods that eventually lead to improvement. Another set of challenges can arise when innovation efforts are decentralized, such as who should be held accountable for measuring efforts that might be spread across multiple agencies or even multiple sectors. According to Phoenix Budget and Research Director Mario Paniagua, City Manager David Cavazos’ approach is to empower department heads by pushing authority down but also by

holding them accountable for developing and implementing innovations by reporting back to him. Cavazos, in turn, is “accountable to the Mayor and City Council on this issue.” Additional oversight comes from the city’s Innovation and Efficiency Task Force, which Paniagua cochairs, and the Finance, Efficiency and Innovation Subcommittee of the City Council (personal communication, July 2, 2013).

Budget and Staffing. Budgeting for efforts to promote and support innovation is, of course, another critical consideration. Key details include the size of the budget, the sources of funds (both public dollars and, if any, private dollars), how the money is spent (between personnel, training, technology, programming, evaluation, etc.), and the process for disbursing grants and contract dollars to agencies and to providers. The authors found a significant range of budgets and staffing arrangements among the cities interviewed. For example, Colorado Springs (a city of 436,000) allocated in 2013 about 0.11 percent of its general fund to the Department of Administrative Service and Innovation ($245,000 out of a total city budget of $232 million) (City of Colorado Springs, 2012). By contrast, New York City (with over 8.2 million people) allocated in FY2013 $76.5 million of its overall budget of $50.8 billion to CEO in FY2013 (City of New York OMB, 2013). However, CEO’s budget represents 0.15 percent of the overall city budget, which is comparable with that of Colorado Springs’ innovation office.

Despite the uniqueness of New York City’s size, CEO does provide a useful example of how an innovation office might conduct its budget process. CEO’s public dollars are allotted by the city’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) out of the city’s miscellaneous budget. Once a new pilot program is established, CEO requests that OMB transfer funds to the lead city agency. Providers then compete for contracts through a traditional procurement process implemented by the agency in close coordination with the Mayor’s Office of Contract Services or purchasing department. Most contracts follow a traditional timeline of three years with a renewal option of one or two years.

CEO has the most staff members of any innovation office that the authors have identified to date —with 18 FTEs in the main office and multiple staff positions funded within agencies to help coordinate CEO programs. By comparison, the Department of Administrative Service and Innovation in Colorado Springs budgeted for two FTEs in FY2013 (City of Colorado Springs, 2012). Philadelphia’s Office of New Urban Mechanics and San Francisco’s Mayor’s Office of Civic Innovation each employ two staff people as well. Related considerations are the types of skills and experience employees bring to the work and the variety of ways a city can incorporate local expertise and talent into its efforts. At CEO, for example, the overwhelming majority of staffers working in summer 2013 had no professional experience in government. Meanwhile, the smaller or decentralized innovation teams in Phoenix, Denver and New York City’s iZone look to increase their reach and impact by organizing advisory boards with leaders in the local business and civic community.

Personnel Rules and Unions. While contractual language and administrative structures regarding public employees can serve as important protections, they can also present challenges to implementing innovation. Work rules are often cited by local officials as obstacles to innovation and reform, and should be closely analyzed on a case-by-case basis to understand both the hurdles they present and the feasibility of altering or eliminating them. That said, fear of provoking a political battle over such rule changes can often be enough to sink an innovation despite its potential. In most cases, it is indeed the mayor or agency head, or both—not the innovation team or office—that negotiates with unions and has direct responsibility for pursuing changes to personnel rules. In these instances, public awareness can play a key role when opposition arises from those invested in the status quo.

Much has been written on strategies to overcome contractual and administrative hurdles to innovation. Among the city officials with whom the authors spoke, reporting on performance is a common approach used to trigger public interest and galvanize support for change. Others suggested building coalitions of support for specific innovations, particularly large-scale efforts that affect significant numbers of citizens. Rather than (or prior to) taking a “fight” public, one approach is to engage unions or other potential opponents early in the process of reform and seek to establish a collaborative approach to change.

In Innovating with Integrity, Sandford Borins uses his research on Harvard University’s Innovations in American Government Awards program to understand the work of public-sector innovators. Borins was surprised that a significant amount of criticism from opponents was based on philosophical differences about whether the innovation represents “good public management or good public policy” (1998, p. 90). Even criticism from public-sector unions was split evenly between philosophical differences and concerns that Borins describes as representing “self-interest,” e.g., lost jobs, negative effects, and work conditions. Faced with these obstacles, Borins recommends persuasion as the primary tactic, and argues that political maneuvering or antagonism should be a last resort. Among the most common tactics deployed by those Borins’ researched were co-optation and targeted and general messaging to highlight the vision and the public value the proposed innovation might create (1998, pp. 72–76). As Sanderijn Cels, Jorrit de Jong, and Frans Nauta write in Agents of Change, often it takes multiple conversations and attempts to introduce and persuade stakeholders of the value of an innovation to their interests and to the public’s interest (2012, pp. 45–48). Also important are sensitivity of language and messaging to potential opponents, and adapting an innovation or reform so that potential supporters recognize the benefits (Cels et al., 2012, pp. 182–183; p. 191).

The Costs of Measurement. Investment in evaluation is critical to effectively understanding and communicating the value of innovation efforts. Recent analysis by Borins found that innovative programs that have been evaluated internally are more likely to be transferred or replicated, to receive outside validation such as awards and to attract the attention of various media (personal communication, June 10, 2013). That said, the challenge for many cities is the cost to conduct evaluation. Depending on the rigor and scope, efforts to evaluate initiatives and strategies to promote and support innovation can be quite costly, in terms of both money and personnel. As Carson Hicks noted, in CEO’s early days, citizens, city councilors and other stakeholders regularly “questioned whether CEO’s spending on evaluation was an appropriate use of public funds” (personal communication, December 17, 2012). Over time, as the demand for evidence and performance data has become more the norm, Hicks says that earlier skepticism has yielded to regular communication and even—in the case of city council staff—collaboration on new program models (personal communication, July 1, 2013).

|

“If you want to truly make the most out of your dollars then it’s important to know whether or not something is in fact working.” —Carson Hicks, Director of Programs and Evaluation, CEO (personal communication, December 17, 2012). |

Lower-cost evaluation strategies include collecting and analyzing data in-house or when possible utilizing relevant data from third parties (e.g., the federal government, community foundations and local universities). Jon Katzenbach, Ilona Steffen and Caroline Kronley offer two other cost-saving tips for measuring innovation in their recent article on culture change in the Harvard Business Review. First, incorporate measures and indicators into existing performance measurement efforts. “It’s better to include a few carefully designed, specific behavioral measurements in existing scorecards and reporting mechanisms, rather than invent extensive new systems and surveys.” Second, they suggest evaluating a subset of departments or employees “whose own behaviors have a disproportionate impact on the experiences of others” (2012). Additionally, agencies or departments might share the costs of evaluation; New York City’s iZone does this with the schools in its network. A central innovation office might similarly share its assessment costs with its partner agencies. Attracting resources is likely to require clearly and regularly communicating the necessity of measuring this work and its benefits—including cost savings and impact.

Continuity Across Administrations. As a final consideration, city leaders should structure innovation activities to ensure that future administrations will sustain their efforts. Institutionalizing efforts to support and promote innovation is an important approach to durability. For example, while mayoral support can be crucial to the initial success of activities in support of innovation, efforts that are viewed in the future as too closely aligned with a mayor can face the risk of not surviving the transition to a new administration. Utilizing tactics such as incorporating innovation and efficiency targets into annual department reviews—similar to the city of Phoenix—can help institutionalize efforts. Another approach to durability is to build constituencies (either within or outside government) that support or are otherwise invested in efforts to promote innovation. For an innovation team or office, internal relationships with agencies across city government with whom it is partnering (and perhaps trying to influence) are particularly important. For example, CEO has learned through regular collaboration with city agencies that allowing decisions to be made at the agency level can be helpful in building ownership within agencies of their efforts to promote and support innovation.

Smaller innovation teams that lack significant personnel or financial resources might struggle to incorporate even the most promising innovations across city agencies. Boston’s Mayor’s Office of New Urban Mechanics addresses this challenge in part by engaging staff at partner agencies early on in the ideation and design process, helping to both incorporate the experience and perspective of frontline staff at a practical level, and ultimately build more buy-in (James Solomon, personal communication, January 3, 2013). This partnering strategy could also help to build skills within agency staff and lay the foundation for future innovation—no matter the fate of an innovation office, initiative or team.

Denver’s Office of Strategic Partnerships (DOSP) managed to survive a recent transition in mayoral administrations. Director Dace West attributes DOSP’s durability to a number of factors. Regularly interacting with city agency staff in its work, West believes, has helped make clear the value of DOSP to city government. Likewise, its focus on partnering with an array of nonprofits in the city helped strengthen its reputation and attracted advocates. When the time came, the needed political support for DOSP came from not only city agencies but also the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors, as well as community-based partners. Additionally, staffing the office with a nonpolitical position through an established funding stream protected the director’s job when other department heads and political appointees transitioned out. Finally, West believes that DOSP’s flexibility was important, which in practice meant embracing the new mayor’s priorities and “looking for opportunities where the administration’s values and our own aligned” (Dace West, personal communication, May 6, 2013).

V. Conclusion

This paper concludes the three-part miniseries on “Improving the Local Landscape for Innovation” in public problem solving, published as part of the Occasional Papers Series from the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. The first paper introduces readers to the nature of this work by highlighting the experiences of three cities actively driving innovation. The second paper details a comprehensive framework that cities might utilize to improve the local landscape for innovation. This framework builds on previous research in public-sector innovation and establishes a set of strategies that focus on increasing capacity, rethinking policy and developing a culture in support of local innovation.

In this third and final paper, the authors turn toward implementation of the framework’s strategies. Continuing their approach of grounding the project in real-world practice, they introduce a tool that cities might use to assess their efforts towards improving the local landscape for innovation. In developing this assessment tool, the authors conducted a review of similar or analogous efforts to measure public innovation (a list of selected resources on measuring government innovation is included with this paper). The authors also spoke extensively with the Center for Economic Opportunity in New York City to develop the case study as a conceptual test of the framework and assessment tool and further refined both with the input of CEO and a handful of other cities, including Phoenix, Boston, Denver, Memphis, Colorado Springs and iZone in NYC.

The authors wish for these three papers to be a launching point for further discussion. They hope that cities engaged in designing and pursuing innovation strategies will utilize the framework and assessment tool and participate in its further refinement. The process of creating this assessment tool has revealed that many questions around the framework’s strategies remain unanswered. For example, is the framework truly comprehensive? If not, what is missing? Under what conditions are each of the framework strategies and components most realistic or achievable? Is there an ideal timing or sequence for deploying the various strategies and tactics of the framework? Is the assessment tool effective at measuring performance? In what ways does it provide language and ideas to help communicate the value of the work? Does adoption of the assessment tool, in whole or in part, contribute to the durability of efforts to promote innovation?

In addition to answering some of the questions above, another area for examination is the costs, benefits and hurdles of cities’ efforts to implement these and other strategies to support and promote innovation. Sharing among practitioners will help inform the growing community of public-sector actors exploring innovative solutions to public problem solving.

REFERENCES

Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government. (2012, February 12).

Press release: Center for Economic Opportunity wins Harvard Innovations in American Government Award.

Retrieved from http://www.ash.harvard.edu/Home/News-Events/Press-Releases/Center-for-Economic-Opportunity-Wins-Harvard-Innovations-in-American-Government-Award

Behn, R. (2003). Why measure performance: Different purposes require different measures.

Public Administration Review, 63 (5), 586–606

Behn, R. (2012). PortStat: How the Coast Guard could use performancestat leadership strategy to improve port security. In J. Donahue and M. Moore (Eds.),

Ports in a storm: Public management in a turbulent world. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press

Borins, S. (1998).

Innovating with integrity: How local heroes are transforming American government.

Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Cels, S., deJong, J., & Nauta F. (2012).

Agents of change: Strategy and tactics for social innovation.

Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Center for Economic Opportunity. (2010).

Evidence and impact.

Retrieved from http://www.nyc.gov/html/ceo/downloads/pdf/evidence_and_impact.pdf

Center for Economic Opportunity. (2011).

Replicating our results.

Retrieved from http://www.nyc.gov/html/ceo/downloads/pdf/ceo_report_may_2011.pdf

City of Colorado Springs. (2012).

Annual budget 2013.

Retrieved from http://www.springsgov.com/units/budget/2013/Prelim/2013ColoradoSpringsBudget-10-01-2013.pdf

City of New York. (2013, March 14).

Press release: Mayor Bloomberg, Deputy Mayor Gibbs and Center for Economic Opportunity launch competition to recognize nonprofit innovation in fighting poverty.

Retrieved from http://www.nyc.gov/portal/site/nycgov/menuitem.c0935b9a57bb4ef3daf2f1c701c789a0/index.jsp?pageID=mayor_press_release&catID=1194&doc_name=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.nyc.gov%2Fhtml%2Fom%2Fhtml%2F2013a%2Fpr095-13.html&cc=unused1978&rc=1194&ndi=1

City of New York. (2013, May 9).

Press Release: Mayor Bloomberg and Deputy Mayor Gibbs announce pilot expansion of earned income tax credit as new antipoverty initiative 1.

Retrieved from http://www1.nyc.gov/office-of-the-mayor/news/157-13/mayor-bloomberg-deputy-mayor-gibbs-pilot-expansion-earned-income-tax-credit-new

City of New York Office of Management and Budget. (2013).

The City of New York executive budget fiscal year 2013: Budget summary.

Retrieved from http://www.nyc.gov/html/omb/downloads/pdf/sum5_12.pdf

Government Technology, (2012).

Special report: The government dashboard.

Retrieved from http://www.govtech.com/pcio/special_reports/special-report-dashboards.html

Katzenbach, J. R., Steffen, I., & Kronley, C. (2012). Cultural change that sticks.

Harvard Business Review, July–August.

Retrieved from http://hbr.org/2012/07/cultural-change-that-sticks/ar/1

Metis Associates. (2009).

Evidence of organizational change: Qualitative assessment of the NYC 1 CEO’s impact on NYC agencies and provider organizations.

Retrieved from http://metisassociates.com/publications/downloads/Metis_10-09_EvidenceofOrganizationalChange.pdf

NYC Service. (2012).

2012 annual report.

Retrieved from http://www.nycservice.org/liberty/download/file/943