Summary

The Community Design Collaborative serves as a supportive intermediary between Philadelphia-area nonprofits with specific building needs and skilled volunteers with the expertise to evaluate project ideas and craft the initial designs, a role filled by no other local organization and few others nationally. This formal pro bono intermediary model is relatively uncommon, particularly in the areas of design and building support. But increasing use of such a paradigm could help nonprofit organizations take advantage of professional skills in their communities, and contribute to higher rates of and appreciation for skills-based volunteering by both nonprofit and for-profit entities.

Getting from Ideas to Housing

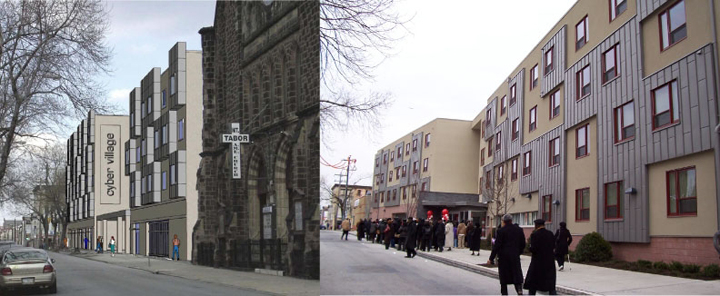

What do a high-tech housing development for seniors in North Philadelphia and a cluster of energy-efficient homes for low-income families in West Philadelphia have in common? Both are remarkable housing success stories, dreamed up by forward-thinking local nonprofit organizations, and brought to reality through the intense efforts of these organizations’ leaders, as well as the assistance of a unique group of designers in getting the initial design plans down on paper.

Nonprofits needing to construct or renovate buildings to enhance and grow the services they offer to the public face a Catch-22. They typically need to raise money for such projects, but to succeed they must present a thoughtful and credible plan to funders. It is nearly impossible to obtain capital funding without predevelopment, but predevelopment work is expensive and is seldom a line item in a nonprofit budget.

Philadelphia-area nonprofits are fortunate to have a local resource to help them bridge this gap between the identified need for and the ultimate realization of adequate financial support to undertake these projects. The Community Design Collaborative matches local design professionals, including architects, landscape architects, historic preservationists, urban planners, engineers, graphic designers and others, with nonprofit organizations in need of their expertise. The pro bono design services offered through the Collaborative help jumpstart nonprofit projects and direct community leaders toward cost-effective, realistic, community-oriented conclusions. Nonprofit leaders are then able to take the design plan generated and present it to potential funders, helping to bring building needs to fruition.

Two local organizations that have reaped the benefits of the Collaborative’s assistance are the Mt. Tabor Community Education and Economic Development (CEED) Corporation and Habitat for Humanity Philadelphia. Both Mt. Tabor CEED and Habitat for Humanity Philadelphia were able to pursue bold ideas in part because the assistance they received from award-winning design firms illustrated that their visions were achievable.

The genesis for Mt. Tabor Cyber Village, a development that offers low- and moderate-income seniors an affordable and engaging place to live, arose a decade ago with Rev. Martha Lang and Rev. Mary Lou Moore, Ph.D., pastors of Mt. Tabor AME Church and leaders of Mt. Tabor CEED. Rev. Lang was concerned that “existing senior facilities were depressing. The seniors were lonely; they spent all day waiting by the elevators for visitors who never came to see them.” Believing that “the Lord placed it in my spirit to create a happy place to live,” Rev. Lang began work with Rev. Moore to create a housing option for seniors where community could flourish.

It took the pastors six years to get control of the vacant lots bookending their church, a process that entailed much more than a simple transfer of title for the land. Rev. Lang recalls the community organizing that was necessary to get the project off the ground: “There was prostitution and drug-dealing behind the church. So at the start of the project we held rallies and walked the neighborhood; we preached them all out by holding Sunday service right in the lot and praying at them through megaphones.”

With the acquisition of the land and community advocacy under way, in 2004 the church approached the Community Design Collaborative for assistance with creating a conceptual design to concretize their vision: affordable rental housing for seniors that uses technology to build a sense of community and connect with the larger neighborhood. The firm of Becker Winston Architects was matched with Mt. Tabor through the Collaborative to help the pastors, and devised a dynamic design that blends with the neighborhood fabric and replicates the rhythm of city row houses with its mix of materials. Today, the pastors’ achievement, sitting amidst a brownstone church, a superblock apartment house and a scattering of row homes, is locally referred to as “the Miracle on Seventh Street.”

Across town in West Philadelphia, on a September morning in 2009, Habitat for Humanity Philadelphia celebrated the culmination of a 5-year home-building project when the Wright, Wanamaker and Seawright families received the keys to their new, LEED-certified homes. Each family had dedicated 350 hours of “sweat equity” to building their houses, a core tenet of Habitat’s institutional mission. Though all Habitat for Humanity building efforts are meaningful for the families who benefit from getting new housing, this project was of particular importance because these homes are part of a seven-unit affordable housing development designed to have low energy costs.

In 2005, with the assistance of the Community Design Collaborative, Habitat for Humanity Philadelphia began working with the architecture firm of Wallace Roberts & Todd and the Energy Coordinating Agency, which strives to support sustainable and energy-efficient building in Philadelphia, to perform a feasibility study for the project. The goal was to develop a sustainable design that would still be consistent with the composition of the surrounding neighborhood. The partnership included donated pro bono design services worth over $21,000. The resulting design became a pilot for Habitat’s LEED certification for homes program and offered proof of concept for a style of construction that meshes with the surrounding architecture, is energy efficient, and can still be built by volunteers.