Summary

In a city that was in need of a customer service operation, Philly311 innovated, in lieu of limited resources, to connect citizens with city government in almost every way possible.

Brief History

When Michael A. Nutter was elected mayor of Philadelphia in 2007, a centralized customer service non-emergency operation did not exist within the city government. If citizens wanted service or had a general question about city services, they often had to call multiple numbers before reaching the appropriate agency to handle their concerns. The result was citizens’ being passed off from agency to agency with more roads leading to cul-de-sacs than resolutions.

In 1996, the City of Baltimore became the first city in America to centralize non-emergency contact with a 311 service. The 311 service would not only be equipped to accept a large quantity of citizen interaction but also work as the “spinal cord” of municipal services, connecting citizen complaints with the work systems of various city departments (“311 Non-Emergency Systems,” 2013). While Philadelphia Mayors Ed Rendell and John Street observed the Baltimore311 system from afar (The Pew Charitable Trusts Philadelphia Research Initiative, 2010), a Philadelphia 311 was not made a public priority until Mayor Nutter promised to have a system implemented by then end of 2008, his first year in office (VernAnastasio, 2008).

Challenge

With public anticipation, then Managing Director Camille Barnett oversaw the implementation of the Philadelphia 311 system on the shortest deadline of a city its size ( City of Philadelphia, 2009). Nearing December 2008’s deadline, the national recession resulted in a sharp decrease in tax revenue in October. What had before been an approximate $5–8 million start-up budget dramatically fell to $2 million (The Pew Charitable Trust, 2010). The financial drought brought the 311 system’s Implementation Phase II (Technology Implementation) (City of Philadelphia, 2009) to a halt. The City could no longer afford to equip Philadelphia’s 311 with a robust customer relationship management system (The Pew Charitable Trust, 2010). The City also abandoned its plan to hire experienced contact center agents to work in 311 and used existing city staff from various agencies.

With the determination to follow through on their promise, Mayor Nutter stood with Managing Director Camille Barnett and 311 Director Rosetta Carrington Lue to cut the “red tape” officially opening Philly311 on October 28, 2008. While also keeping true to the 11-month-old promise, the existence of Philly311 also aligned with Mayor Nutter’s Goal 5 on his strategic goals for the City of Philadelphia. The goal read that “Philadelphia government works effectively and efficiently, with integrity and responsiveness.” Philly311 would be charged with heading up the customer service operations for the city’s 1.5 million residents

(http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/42/4260000.html). To accomplish this task, the center had patched-up, low-cost technology, an inexperienced staff (50% had customer service experience; 100% did not have outside contact center experience) and next to $0 to spend on anything but day-to-day operations (R. Lue, personal communication, September 2013). The need for innovation grew out of the conjunction of a mayoral commitment to customer service and a lack of resources. What resulted was that Philly311 evolved into more than a non-emergency contact center. Under current Deputy Mayor and Managing Director Richard Negrin, Esq., Philly311 became a platform to launch innovative and empowering customer service initiatives, changing the way citizens interacted with Philadelphia City government. The Philly311 operations have received numerous awards over the last four years, including being designated as a Citizen-Engaged Community by the prestigious Public Technology Institute (PTI) for its customer-centric multi-channel communications approach for city residents.

External Innovations

Upon its implementation, Philly311 officially used the tagline: “Your Connection to City Hall.” Although the center received 1.2 million calls in its first year, a $0 marketing budget left many Philadelphians in the dark about the service. To truly connect citizens with City Hall, Philly311 needed to be creative about how they used their limited resources.

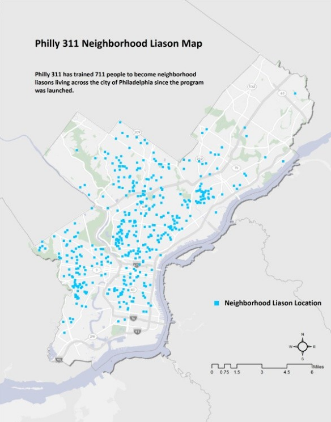

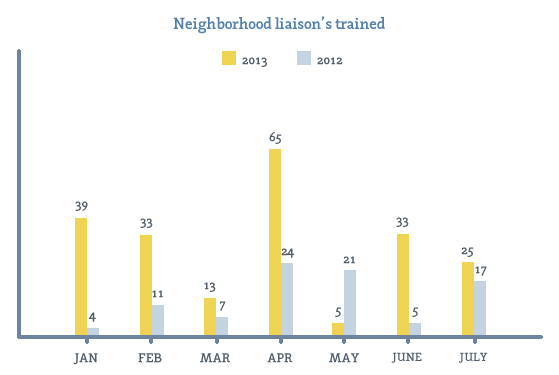

In 2009, 311 Contact Center Director Rosetta Carrington Lue, created the Philly311 Neighborhood Liaison Program in a grassroots effort to bring the 311 service into the community. The idea behind the program was to empower citizens through both education and access. Citizens would first sign up for a one-hour training session, usually held at a community center. A Philly311 representative would then spend the time formally training citizens on how to enter requests directly into the 311 systems. By the end of the session, attendees would have a personalized 311 account through which they could access the 311 portal, enter requests and check the status of previously submitted requests. Philly311 neighborhood liaisons would become empowered, centralized voices within their communities.

While the Neighborhood Liaison Program was successful as an empowerment tool for citizens, it also served another purpose. Because neighborhood liaisons were trained by Philly311 employees and had personal, back-end interaction with the system, they inadvertently become “grassroots” customer service and marketing representatives within their communities. These liaisons were knowledgeable enough to answer their neighbors’ questions about city services. They could also encourage neighbors to use the service, citing personal experience with results. Since the program launched in 2009, 711 neighborhood liaisons have been trained across the city (as of August 2013), and the program continues to grow.

With the Neighborhood Liaison Program’s success, the Philly311 team saw the value of education in a customer service operation. This spawned the idea for a Citizen’s Engagement Academy in 2010. Eight weeks long, the academy would educate citizens on the resources available to reduce blight and violence in their communities. Each week would feature a leader from a different municipal entity—this leader would give a presentation on his/her respective resource and then field any questions citizens may have. The academy included presentations from the Philly311 Neighborhood Liaison Program, Town Watch Integrated Services, the Public Nuisance Task Force and the Philadelphia More Beautiful Committee, among others.

The Citizens Engagement Academy has since been adopted by the PhillyRising initiative within the City of Philadelphia’s Managing Director’s Office. Per its mission, “PhillyRising targets neighborhoods throughout Philadelphia that are plagued by chronic crime and quality of life concerns, and establishes partnerships with community members to address these issues” (http://www.phila.gov/phillyrising/index.html). By bringing the Citizen’s Engagement Academy to some of the city’s most crime and blight-ridden neighborhoods, city government is able to empower citizens through education and access in a way that had not available to their communities in the past.

Internal Innovation

Both the Philly311 Neighborhood Liaison Program and the Citizen’s Engagement Academy proved to be assets to the city government’s customer service operations. For the operation to truly be effective, however, Rosetta Carrington Lue, who was promoted to executive director and chief customer service officer, knew that there needed to be an internal training effort. In 2011, the Customer Service Leadership Academy was born. The academy offered a catalog of courses to city employees for professional growth in the area of customer service. An initiative for professional growth had never before been launched in Philadelphia city government.

The Customer Service Leadership Academy catalog included courses such as: Basic Customer Service Telephone Skills; Face-to-Face Interaction for Non-Call Center Employees; How to Effectively Handle Customer Complaints; Email Etiquette; and Basic Time Management Skills for Non-Managers, among others. While Lue and the Philly311 team knew that peer-to-peer mentoring was the most effective training method, Philly311 employees acted as the instructors for the majority of these offerings.

To increase the effectiveness of the professional growth initiative, the Customer Service Leadership Academy turned to the private sector. Offering almost all pro bono work, managerial consulting firm Blue Isis worked with Rosetta Lue to develop fifteen “mini-courses” for city employees (PR-inside.com, 2013).

The response from the offering was eye opening. Every class, scheduled for a capacity of 20 employees, received requests from between 40 and 100; each of the 15 classes filled up within three days. Core courses focused on presenting project management fundamentals that could be immediately applied on the job. The catalog of courses covered important soft skills that apply to both line and project management situations such as Giving and Receiving Feedback and Best Practice Principles for Productive Meetings. The City of Philadelphia employees were hungry for professional growth. To date, the Customer Service Leadership Academy has seen over 2,000 participants.

Philadelphia Police 311 Technology Enhancement

In 2011, Philly311 made another effort to strengthen the City’s frontline customer service operations. The Police Mobile Data Terminal (MDT) Program was launched to equip City of Philadelphia police vehicles with the ability to enter service requests from the field. With this capability, citizens could complain to a police officer about an abandoned building, a licenses issue, graffiti or any other non-emergency issue and the officer could report the issue from his or her vehicle. The initiative meant more customer service representatives in more areas of the city. To date, 1,032 Philadelphia police officers have access to the 311 system.

Philly311 Goes Mobile

While Philly311 had developed an arsenal of customer service tools, the team wanted to bring the 311 service to those who had adopted a mobile lifestyle as well as those living on the other side of the digital divide. In Philadelphia, 41% of residents do not have home Internet access (City of Philadelphia, 2011). This number, however, does not reflect the number of citizens with Internet access via a smart phone. In September 2012, Philly311 worked with vendor PublicStuff to launch the Philly311 mobile app to open a more convenient customer service channel as well as to serve the city’s poverty-stricken population.

The app, available free for iPhones, Androids and Blackberrys, gave users the ability to enter service requests from their smart phones. Users could take a picture and add a personalized description to their service request in addition to viewing service requests made near their geographic location. The mobile app also included a directory of city officials, city news and videos.

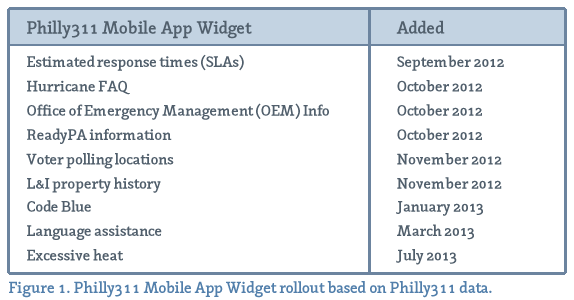

The capability to enter service requests from any smart phone was a monumental step forward for the city’s customer service operation, but the mobile app also proved to be a vehicle for a more instantaneous and versatile government. The first example of this came in late October 2012, when Hurricane Sandy hit the region. Prior to the storm’s arrival, the mobile app team added a “Hurricane FAQ” widget to the mobile app—citizens were urged by Mayor Nutter and Managing Director Richard Negrin to download the app and contact 311. On Monday, October 29, 2012, the Philly311 mobile app was the 33rd most downloaded app in the iTunes store (O’Byrne, 2012).

Other examples of added widgets included the “Election Day” widget, which gave users a polling locator and candidate information as well as voting rules for the State of Pennsylvania. Later in November 2012, the mobile app team released the “Licenses and Inspections” widget, allowing users to enter a specific address and view its property history. In response to the 2010 census data revealing that 21% of Philadelphia residents speak a first language other than English, the Philly311 mobile app became the first 311 app in the country to dynamically translate communication between users and city government in 16 different languages (City of Philadelphia, 2013).

Since the September 2012 launch, the Philly311 mobile app has been downloaded 15,600 times.19 The app was also the recipient of City Paper’s 2012 Big Vision Award in the category of government and politics in addition to being named a Significant Achievement in the Public Technology Institute’s 2013 Technical Solutions Awards.

Philly311 Today

Although the Philly311 Non-Emergency Contact Center was implemented under unfortunate financial constraints, the team behind the center created innovative customer service channels, making Philly311 the wide-spanning customer service platform it is today. To date, Philly311 has received 5.2 million calls, averaging 1.2 million calls each year. There is also a Philly311 walk-in center, a Web self-service portal, a mobile app and the increasing Philly311’s social media platforms, primarily Facebook, YouTube and Twitter.

Philly311 Future Community Engagement Initiatives

Looking ahead, the Philly311 team is in the process of filming The Philly311 Show, to be aired on Philadelphia’s Channel 64. The show will feature interviews from the city’s leaders and frontline employees in an attempt to give citizens a more personal look into city government. The Philly311 team also recently launched the pilot phase of a youth neighborhood liaison program—bringing mobile-app-driven contests into area schools community associations. The operation is also launching a new customer relationship management technology platform over the next 12 months that will continue to improve both internal and external customer interaction with city government.

In a city that was in need of a customer service operation, Philly311 innovated, in lieu of limited resources, to connect citizens with city government in almost every way possible.

References:

311 Non-emergency systems. (2013, September).

Dispatch Magazine On-Line.

Retrieved from http://www.911dispatch.com/3-1-1-systems/

City of Philadelphia. (2009).

Philly311: The first 100 days.

Philadelphia, PA: P. Morgan, J. Friedman, & R. Lue.

Retrieved from http://icma.org/en/icma/knowledge_network/documents/kn/Document/102137/Philly311_The_First_100_Days

City of Philadelphia. (2011).

Mayor Nutter, People’s Emergency Center continue “Freedom Rings Partnership.”

City of Philadelphia’s News & Alerts.

Retrieved from http://cityofphiladelphia.wordpress.com/2011/06/13/mayor-nutter-people

City of Philadelphia. (2013).

Philly311 mobile app available in 16 languages.

City of Philadelphia’s News & Alerts.

Retrieved from http://cityofphiladelphia.wordpress.com/2013/03/22/philly311-mobile-app-available-in-16-languages/

O’Byrne, J. (2012, November 28).

Non-Emergency 311 Centers Can Save Lives: The Philadelphia Story [Web log post].

PublicStuff Blog.

Retrieved from http://publicstuffblog.publicstuff.com/tag/philly311/

The Pew Charitable Trusts Philadelphia Research Initiative. (2010).

A work in progress: Philadelphia’s 311 system after one year.

Philadelphia, PA: T. Ginsberg.

Retrieved from http://www.pewtrusts.org/uploadedFiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/Reports/Philadelphia_Research_Initiative/FINAL

PR-inside.com. (2013, January 28). City of Philadelphia improves project management capabilities.

Retrieved from http://www.pr-inside.com/city-of-philadelphia-improves-project-management-r3565615.htm

VernAnastasio. (2008, January 29).

Accountability is on the way: Nutter admin. embraces CitiStat [Web log post].

Young Philly Politics Blog.

Retrieved from http://youngphillypolitics.com/accountability_way_nutter_admin_embraces_citistat

11. Philly311 data.

14. Philly311 data.

15. Philly311 data.

19. Philly311 data.