EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Migrant and Refugee Health experts (WHO) indicate that more people are on the move now than ever before. This rapid increase of population movement has important public health implications, and therefore requires an adequate governmental response. Ratified international human rights standards and conventions exist to protect the rights of migrants and refugees, including their right to health. Nevertheless, many refugees and migrants often lack access to health services and financial protection for health. COMMUNITY HEALTH recognizes that effective approaches to serve and engage remote and rural, indigenous, migrants and refugees, women, and elderly populations, often contrary to mainstream health policy, are often ignored, not included, or recognized in global, national, region policies and practices that inform mainstream practices. The overarching research question driving this policy action is: what are promising practices that can assist governments in implementing initiatives to promote the health of immigrant and refugee populations? The methods we employed are: 1) a review of the literature on best practices, 2) case study analysis of promising practices across two developed and one developing country, and 3) lectures and conversations with experts knowledgeable about such practices. Our findings indicate that initiatives to facilitate sustainable cross-government collaborations and incorporation of immigrants and refugees into the formal workforce including the health care sector are essential for governments to live up to the health as a human right standard. Failure to act will results in human rights violations, loss of economic power, severe strain on health care systems, increases in conditions exacerbated by social determinants of health such as substance use, violence, and infectious disease rates.

CONTEXT

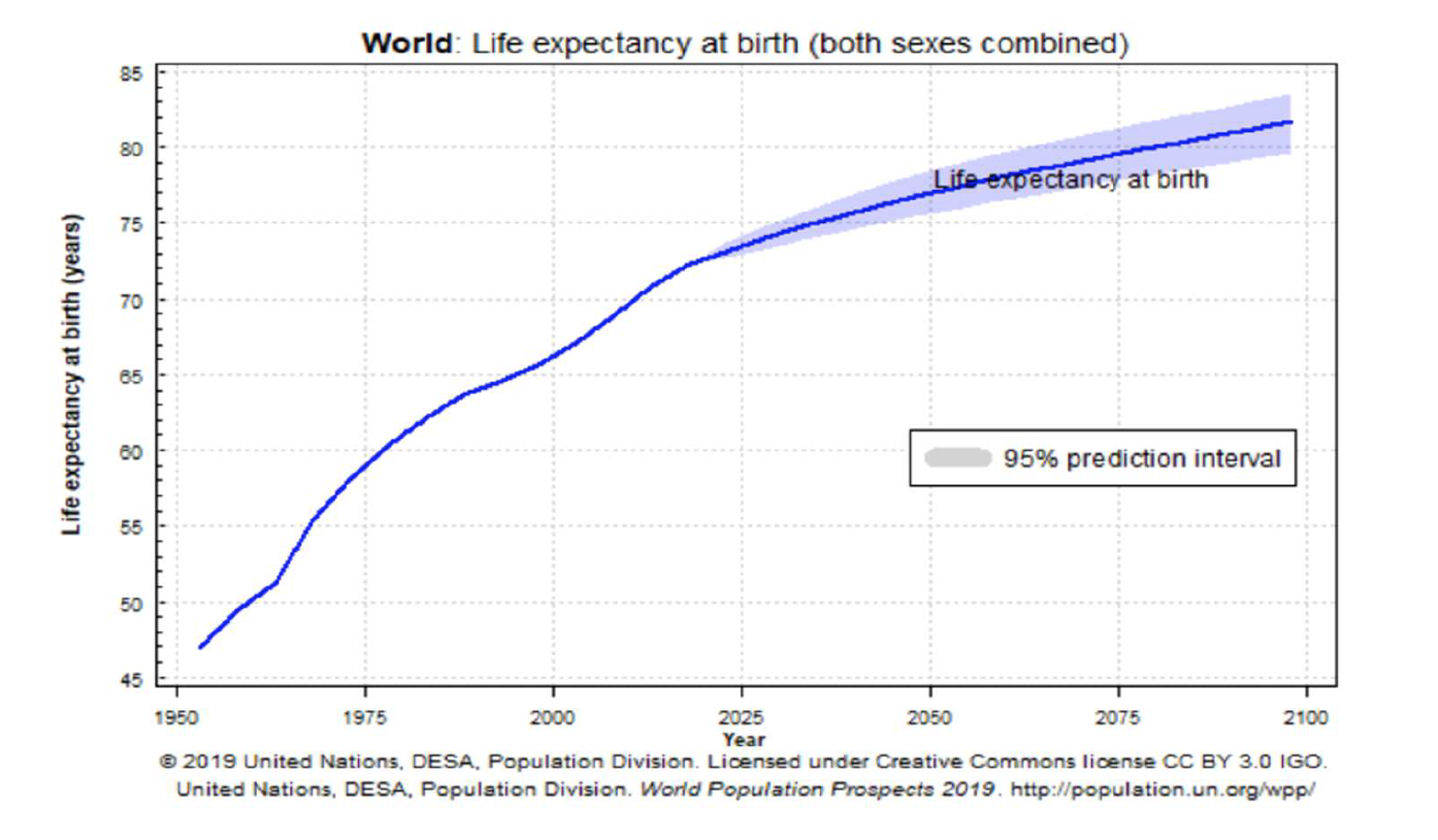

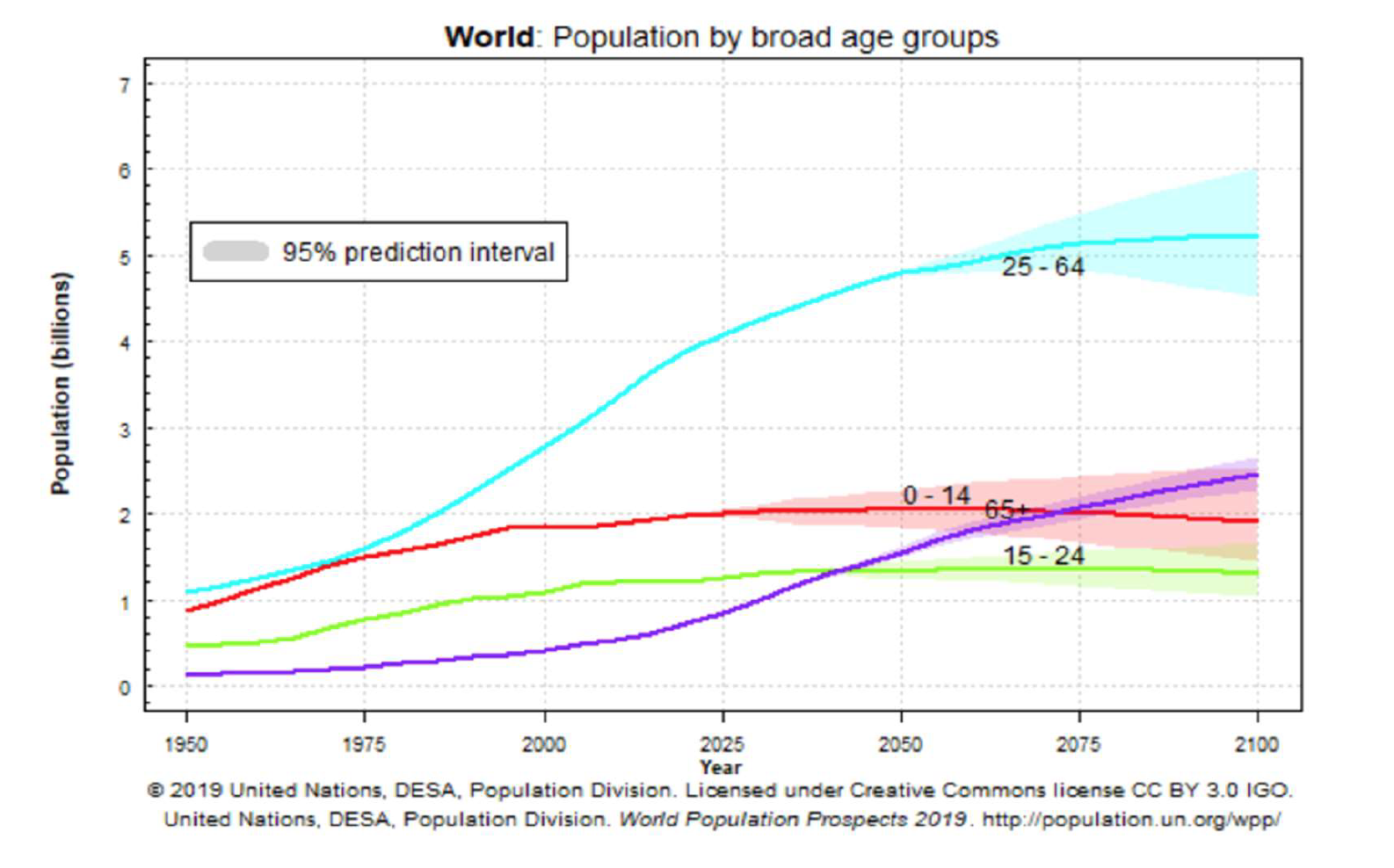

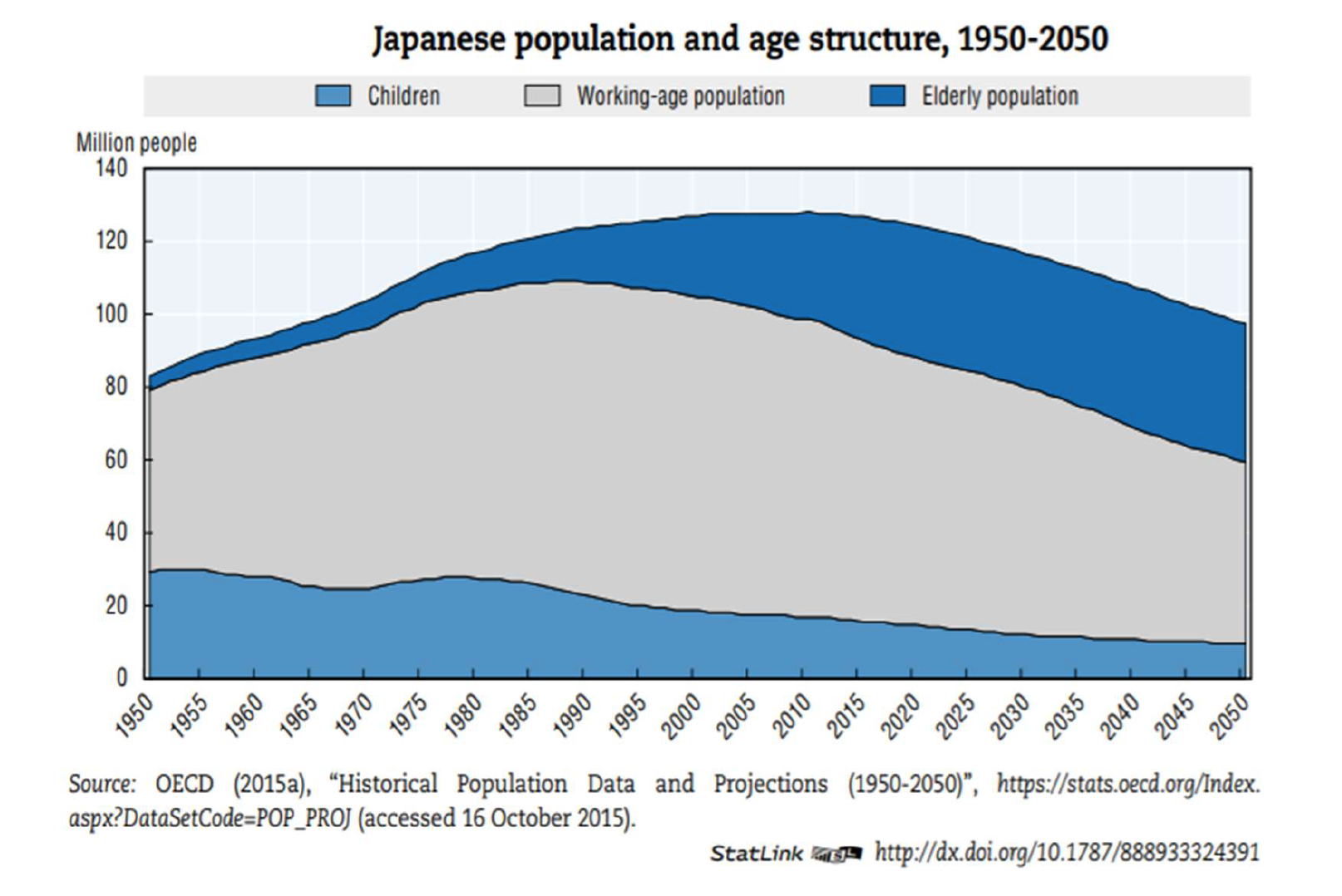

The world’s immigrant population is on an unprecedented rise. Today, approximately one seventh of the world’s population, or 1 billion, is composed of immigrants (World Health Organization 2020). A primordial motivation for immigration is search for a better life which includes securing an education, employment, housing, and human rights protections (Klinger, 2020). The unprecedented rise of immigration around the globe is here to stay as it is fueled by the increased globalization and conflict, climate change, economic instability, and infectious disease seen in many countries around the world. As a result of the ubiquitousness of immigration, the profile and demographic characteristics or immigrants are changing. For example, in the U.S., which receives approximately 40% of the world’s immigrants, today’s immigrants are more likely to be educated, women, older adults, children, and refugees compared to a decade ago (Radford & Krogstad, 2019). These changes in trends signify a need for national governments to shift their policies and approaches to accommodating immigrants and refugees in order to abide by the human right to health. Immigrants and refugees intersect with every aspect of society including the economy, education, health care, and policy sectors

(National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2017). It is important to consider the evidence indicating that immigrants, if given the opportunity, are important contributors to the economy of nations. In the U.S., it is estimated that immigrants contribute approximately $2 trillion to Gross Domestic Product by working at higher rates, supporting the elderly, and raising children who in great proportions exhibit upward social mobility (U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, undated).

Unfortunately, immigrants and refugees are often disproportionately impacted by social determinants of health as they face many challenges that place them at high risk of morbidity and mortality severely limiting their potential economic contribution. Many face treacherous journeys from their country of origin to the new destination and at the new destination face hostile immigration laws, policies and procedures that expose them to increased discrimination, violation of human rights, violence, detention, incarceration, lack of integration and access to health care services, unemployment, and lack of affordable housing (Casillas, 2006).

The purpose of this policy/action paper is to highlight the initiatives that promote the priorities set forth by the WHO at a regional and local level underscoring how state and Local governments are ideally positioned to implement policies and practices that will most immediately contribute to the well-being of immigrants and refugees as they are at the frontlines. Promising partnership initiatives by South Africa (developed country), Mexico (a developing country) and two U.S. states (a developed country): New Mexico and Texas, on the U.S.-Mexico border will be discussed. Recommendations made are supported by a review of the literature and conversations with experts facilitated by the TUFH Migrant and Refugee Institute.

PRIMARY RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The following includes the non-exhaustive list of primary research questions driving our review of the need for Migrant and Refugee Health, and a recommended path for integration with health and education policies:

- What are best practices to build and/or strengthen bi-national infrastructure and collaborations?

- How can bi-national initiatives support Refugee Doctors and Health Care Professionals in the care of refugee and migrant communities?

- How can Community Health Workers or other Health Professionals be trained and integrated into the care of immigrant and refugee communities?

- What complementary strategies can be incorporated into existing health policies? Can economic empowerment contribute to the reduction in vulnerabilities to communicable diseases for immigrants?

- How can the private sector be attracted to participate in initiatives protecting immigrants’ health?

- What facilitates the sustainability of initiatives to promote a long-term impact on targeted populations?

METHODOLOGY

To explore the primary research questions, the development of this policy action paper included the establishment of terminology; a review of literature; integration of expert lectures and case studies via the TUFH Migrant and Refugee Institute; and content from interviews with global content experts.

ANALYSIS/FINDINGS

Literature Review Findings/Analysis

Our literature review yielded information about innovative practices and indicated that bi-national agreements, coalitions, community-academic partnerships, and harnessing the power of technology are powerful tools that can bring sustainable capacity across systems to address the health needs of immigrants. In particular, building an informatics infrastructure seems essential to build capacity in the cross-sector collaborations within countries. Five components are proposed by Bakken as the building blocks of a solid infrastructure: 1) standardized terminologies and structures, 2) digital sources of evidence, 3) standards that facilitate health care data exchange among heterogeneous systems, 4) informatics processes that support the acquisition and application of evidence to specific clinical situations, and 5) informatics competencies. Presently, major barriers to data sharing are present including differences across countries in the provision and enforcement of laws that protect the confidentiality of patient medical information. Today, powerful technological innovations may facilitate the confidential exchange of information. However, political will and implementation of practices to facilitate trusting collaborations may be a precursor to data sharing.

Case Study Examples/Findings/Analysis

Initiatives, lessons, and recommendations from two case studies are discussed below. In the following section, promising practices to promote cross country collaborations and their implications for actions/strategies to promote the health of immigrants and refugees are discussed.

Case Study: The U.S.-Mexico Border, United States

The U.S.-Mexico border, a land stretch of 2,000 miles is the largest binational border crossing in the world. Four U.S. states including California, Arizona, New-Mexico, and Texas border six Mexico states. In 2019 alone, 610,000 undocumented immigrants crossed this border. The U.S.-Mexico border is an area characterized by diversity in terms of culture, economy, and disease profiles of residents as a developed nation meets a developing one. There is high cross-border mobility due to the economic interdependence yet sharp distinctions in the demographic characteristics of U.S. and Mexican residents.

The area is also a primary destination for immigrants. For example, in 2019, approximately 300,000 immigrants from Central America arrived to border cities with the intention to cross into the U.S. This region of the world, as many others, is seeing an unprecedented increase in the number of immigrants fleeing conflict and extreme poverty. As stated above, the demographic characteristics of immigrants are changing and this trend is reflected in the profile of recently arrived immigrants to the U.S.-Mexico border. Estimates indicate that a greater percentage of women and individuals > 60 years, than a decade ago, make up the migrant population. In 2018, 29% of migrants entering Mexico bound for the U.S. were women compared to < 10% a decade ago (Franco & Alcantar, 2019).

The primary challenges that the U.S.-Mexico border faces include binational health care use, a high proportion of uninsured or underinsured individuals, and a high proportion of families with members who have mixed immigration statuses, migrant laborers, farmworkers, recent immigrants and undocumented immigrants. Public health issues are broad but reproductive and sexual health epidemiologic profiles suggest this is a health issue of special concern. For example, there is a very high birth rate coupled with high rates of unwanted pregnancies, reproductive cancers, gestational diabetes, and sexually-transmitted diseases. Although each country has initiatives to promote sexual and reproductive health, efforts to address the needs of a binational/bicultural population that accommodates the needs of each country’s epidemiological and cultural profile is needed. Despite these challenges, several U.S. states and Mexico are devising and implementing initiatives, strategies to learn about the best efforts each country is leading and set objectives to strengthen the local infrastructure to improve the health and well-being of immigrants. This part of the world is not unlike other border crossings around the globe. Several initiatives and strategies put forth by U.S.-Mexico border entities can serve as an example of potential strategies that can be employed by nations around the globe in a concerted effort to improve the health of immigrants and refugees. Several initiatives undertaken will be described with implications for initiatives to safeguard the health of immigrants and refugees around the world and in the settings described including strengthening the capacity of health care systems which in many parts of the world are already strained.

The U.S.-Mexico Border Health Commission (USMBHC (Southern African Development Community, undated) is a premier example of a binational collaborative grounded in the human right of individuals to health created by medical health providers and advocates. The main goal of this collaborative is to provide leadership in developing and implementing initiatives to optimize the health of U.S.-Mexico border residents, including immigrants and refugees. On July 2000, the United States and Mexican governments entered into a formal agreement to establish the USMBHC motivated by the recognition that the lives and health of border residents is intertwined. The USMBHC operates from four offices across four U.S. states and six corresponding offices across the six Mexican states that make the U.S.-Mexico border. Each office has a close collaboration with the corresponding state health departments and funding is provided by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Mexican Ministry of Health. A primary objective of the commission is to identify health priorities and target such priorities with a variety of initiatives to address infectious disease (e.g., the U.S.-Mexico border Tuberculosis Consortium); chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes prevention (e.g., Binational Obesity and diabetes prevention and awareness campaigns); and Health insurance Education and Marketplace initiatives (e.g., Workshops to educate residents on insurance options based on the affordable care act). Three important initiatives set forth by the USMBHC include: 1) The Healthy Border 2020: A Prevention and Health Promotion Initiative; 2) Establishment of a local surveillance system to generate data specific to the binational border population to enable the planning and assessment of targeted initiatives; 3) Training community-health workers to strengthen the local health care infrastructure and workforce; and 4) Building sustainable coalitions and academic-community partnerships bringing together key stakeholders, community based and governmental organizations, and politicians to engage in mobilize action, promote strategic planning, research, and collaboration. The USMBHC is an example of a successful binational collaboration that has assisted in the planning and implementation of several initiative to improve the health of border residents. The four key initiatives named above will be expanded upon below along with implications and recommendations for extending the reach of initiatives to improve the health of immigrants and refugees.

The Healthy Border 2020: A Prevention and Health Promotion Initiative. The USMBHC began to formalize its collaboration beyond signing of an agreement by forming a commission: The U.S.-Mexico Border Binational Commission. The commission was directed to develop a framework to advance public health goals in the region and actions to promote these. The result was a comprehensive report titled: The Healthy Border 2020: A Prevention and Health Promotion Initiative . The report provides detailed information about the demographics of the region highlighting the social determinants of health impacting residents and guidance on priority health areas to address. Information also includes baseline data and specific strategies to improve health and advocate for resources and facilitating collaborations across governments. This framework represented an important step in formalizing collaborations as it provides specific directions and measurable targets facilitating the engagement of a variety of actors in initiatives. Potential interested entities include governmental, non-governmental, academic, and other stakeholders. The initiatives discussed below are the result of priorities highlighted in this report and initiatives being undertaken by a variety of actors and entities.

A review of the document suggests that although the report is sufficiently general to promote the health and well-being of border residents in general including immigrants and refugees, the inclusion of a specific section to guide initiatives to promote their health may be particularly useful to guide strategic planning in this realm. The USMBHC can assemble a task force composed of academics and other key stakeholders knowledgeable about immigrant and refugee health and the specific needs and problems immigrants face in the region. Similarly to the existing report, the section can contain information about the demographics and health priorities of recently arrived immigrants and refugees, including the social determinants of health likely to impact the health and well-being of immigrants and refugees in the region. The endorsement of the USMBHC is likely to promote the dissemination and implementation of initiatives described as this has been the case in the past.

Local Surveillance Capacity Building Initiative. The USMBHC (Nicholas, Mfono, Corless, Davis, O’Brien, Padua, & Fortinsky, 2016). began a surveillance program to remove the barrier of inexistence of local information to guide policy efforts including assessment. Such information is necessary to develop and implement policies, initiatives and programs and evaluate them. Without such information an evidence-based approach to public health cannot be practiced. Although each country has mature surveillance systems, the data collected was considered insufficient to address the varied, culture-specific, complex needs of border region residents which include a large number of recently arrived immigrants and refugees. The sister cities of Brownsville, Texas and Matamoros, Tamaulipas implemented a local surveillance system by engaging community members in collecting and analyzing epidemiological information to improve the health care of women of reproductive age and their children. Importantly, the information generated consisted of risk factors at the physical, behavioral, and emotional levels for the most prevalent diseases (WHO, 2018). For example, through this initiative it was unveiled that low contraceptive use was a primordial barrier to decreasing rates of pregnancy and STIs. The information obtained was used to develop health educational materials addressing the most prevalent barriers evidenced in the population living on the U.S-Mexico border (International Labour Organization, undated). Furthermore, data about cervical cancer 3-year screening, HIV testing during pregnancy, and HIV lifetime testing rates of the Brownsville-Matamoros border residents indicated a much lower prevalence of 68.2% for cervical cancer, 60% for HIV testing during pregnancy, and 36.1% for lifetime HIV testing rates compared to national averages of both countries (International Labour Organization, undated). The collection and exchange of this information assisted the commission in recommending course of action specific to the area surpassing strict confidentiality policies on information exchange and non-standardization of measures that have prevented information sharing between countries.

In a similar vein, a surveillance system can be set in place to assess demographic characteristics, disease profiles, and the most pressing barriers to health that immigrants and refugees experience in a new destination. Such a system is likely to yield information that is locally relevant, easily accessible across countries, and quick to generate and analyze to guide the development of specific public health evidence-based strategies. Presently, it is not known if the surveillance system in place at the Brownsville-Matamoros border has the capacity to devote concerted efforts at assessing recently arrived immigrants. Building capacity to focus efforts here can guide strategic efforts at improving the health of immigrants across nations.

Training of Community Health Workers Initiative. The USMBHC has embarked in another system change initiative to strengthen the health care infrastructure of the region: the training and support of community health workers (CHWs). CHWs assist in developing and implementing health care initiatives in the under resourced and medically underserved U.S.-Mexico border region. This initiative is the result of the strategic priority of improving residents’ access to health care and strengthening the under resourced public health infrastructure of the region. CHWs are trusted, knowledgeable community members who are trained to link individuals to the health care system. Furthermore, CHWs perform health care roles including delivering health preventative information and strengthening the health behavior skills of individuals to facilitate the enactment of health promoting behaviors (Arvey & Fernandez, 2012). Research indicates that CHWs are effective at linking immigrants into systems of care in developed countries such as the U.S. were policies such as the affordable care act allows legal immigrants to obtain health insurance coverage (Findley & Matos, 2015). Research also suggests that CHWs perform other key roles beyond linking individuals into care to conducting outreach and delivery of public health education programs in places where immigrants live and work (Findley & Matos, 2015). In the case of the USMBHC initiative, the CHW model being implemented includes training and support for CHWs to serve as health educators and advocates. It is estimated that approximately 3,500 CHWs are working in the U.S.-Mexico border region (Foster-Cox, Torres, & Adams, 2018). A key role that CHWs perform in the U.S.-Mexico border region is that of advocate and a bridge to service provision. Many U.S.-Mexico border residents, particularly immigrants and those living in settlements lack essential services including water, electricity, and stable housing. CHWs are in a position, through trainings and extensive networking with distinct service providers, where they can become immediately aware of the most pressing needs and mobilize action. In 2014, an unprecedented number of unaccompanied child immigrants arrived at different points of the U.S.-Mexico border. The USMBHC immediately asked CHWs assistance and evidenced how in a matter of a small span of time CHWs mobilized their networks to set in place processes and systems to link minors to services that would be able to assist them safely. The USMBHC provides training on a variety of topics including chronic and infectious diseases, environmental health, and maternal and child health. Importantly, credentialing is a fundamental part of the support provided by the commission and it entails supporting CHWs to attend professional development opportunities through online educational trainings, conference attendance, and other educational opportunities. This latter endeavor is extremely important to promote the credibility of CHWs and their integration into the formal healthcare workforce and enhances sustainability (Torres, Balcazar, Rosenthal, et al., 2017).

A key aspect of implementing and sustaining a CHW program that can be sustainable and truly strengthen binational collaborative efforts is developing a binational system for credentialing. Although CHWs have been involved in the provision and linkage to health care services for centuries around the world, one of the biggest barriers to sustainability is lack of credibility, respect, and integration of CHWs into the formal health care workforce. The USMBHC is actively working on formalizing the CHW trade. As discussed above, immigrants are more likely to be educated than before. Many have a professional degree, including a health-related degree, from their country of origin. Recruiting immigrants who hold professional degrees in health to work as CHWs can assist with their integration and eventual re-credentialing while strengthening the capacity of the health care system in the country of arrival.

Coalition, and Community-Academic Partnership Building Initiative. Another major initiative embarked by the USMBHC to mobilize action, increase advocacy capacity and inter-sectoral collaboration among multiple entities is community health coalitions and community-academic partnerships. Several partnerships have formed in the region to address a variety of health conditions including teen pregnancy (Red de Coaliciones Comunitarias, 2020) and the success and accomplishments of such are reported in the academic and non-academic literatures. Furthermore, entities such as The United States Department of Anti-Narcotic Affairs and the US Embassy in Mexico have provided funding for 5-year initiatives to tackle complex health problems. For example, one such initiative consists of a partnership to develop a network of community coalitions across the border region to promote substance abuse prevention by tackling structural, interpersonal and individual level factors. Nine coalitions across four border communities: Ciudad Juarez, Nogales, Agua Prieta, and Tijuana that varied on urbanicity have been implementing actions to prevent substance abuse. Specific actions include cleaning of public parks to increase access to alternative drug-free recreation spaces, family level interventions to prevent high school drop-out, community level interventions to provide information about the causes of substance use, and promotion of physical activity among individuals at high risk of substance abuse. A coalition is composed of community members who are residents of a specific neighborhood. Several publications reporting on the work and goals accomplished have been produced (Red de Coaliciones Comunitarias, 2020). An analysis of such documents reveals that a framework to encourage engagement and collaboration has been employed including community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles which call for capacity building for engagement including building a sense of community (Brown, Chilenski, Ramos, Gallegos, & Feinberg, 2016). We wish to emphasize the necessity of grounding collaborations on principles that will facilitate the sustainability of partnerships. There is vast literature alluding to such practices which have been delineated to remove the most persistent barriers to partnership building including asymmetries in power.

Analysis from this initiative makes it clear that facilitating community-academic partnerships and the assembly, direction, and sustainability of coalitions to address specific health issues is a powerful tool to bring about grass root sustainable change. Although coalitions are addressing issues that affect immigrants and refugees at unprecedented rates such as substance abuse, there is a need for a network of coalitions to solely address the high priority needs that immigrants face. A network of coalitions working across neighborhoods in a particular region can plan actions to promote the participation of immigrants and refugees in the formal workforce, to increase their access to legal and health care services, and to increase their integration and relocation from detention centers. In the U.S. state of California, such an effort has begun with the purpose of 1) bringing awareness that immigration status is a social determinant of health that can be modified, 2) establishing immigration-informed care in health care settings, 3) building medical-legal partnerships, and 4) harnessing the power and knowledge of local stakeholders and politicians by including them as part of the partnership to advocate for resources (Saadi, Cheffers, Taira, et al., 2017). A review of the literature yielded an innovative strategy that is being implemented in certain countries which is block chaining (Karanja, et al., 2019). This practice is harnessing the power of technology to promote the rapid training and certification of immigrants to increase their participation in the formal workforce. Coalitions can be particularly effective at implementing a strategic plan and ensuing actions and political will to encourage and facilitate adoption of this strategy.

Case Study: South Africa

The number of international and internal migrants are continually increasing in South Africa. According to Mid-Year Population Estimate by Statistic South Africa in 2019, the international migrant population, on average, increases 15,000 every five years since 2006. And the statistics for domestic migration is more significant. It is important to realize that migration is a determinant of health. With the growing migrant population in South Africa, the local government and health system should take action to address health inequalities and increase access to health care for migrants.

It’s acknowledged that South Africa has a high prevalence of communicable diseases such as HIV and Tuberculosis. Migrants are more vulnerable to these diseases due to various reasons including poverty, poor living conditions, and limited access to medical treatment caused by language barriers, and discrimination (Nicholas, Mfono, Corless, Davis, O’Brien, Padua, & Fortinsky, 2016). In order to help mobile and migrant populations prevent and mitigate the impact of HIV along major transport corridors and cross border areas in Southern Africa, International Labour Organization has initiated a regional program called The Corridor Economic Empowerment Project (CEEP). This project focuses on the economic empowerment of men and women working in the informal economy and it requires collaboration between government, trade unions and employers. Different activities are carried out. At the institution and corporate level, it provides funds for small enterprises to run businesses and helps to expand employment opportunities for the migrant population. Besides, it has trained 128 cross border institutions like customs agencies and 76 transport companies to deliver essential knowledge on HIV and AIDS and periodically distribute condoms to the workers (WHO, 2018). By doing so, it builds the competency of enterprises and employers in mitigating the impact of HIV at workplaces. Secondly, it contributes to the agreement signed by ASSOTSI and customs authorities, ensuring that informal workers are not excluded from access to HIV services at border areas. On the migrant worker’s level, the project encourages them to start their own businesses and offers training to improve their business skills (International Labour Organization, undated). This helps to strengthen their economic power and thus reduces their vulnerability to HIV to some extent.

Overall, the program is successful. It reaches more than 164,603 stakeholders and policymakers and leads to the change of national and regional HIV policies towards addressing issues from an economic perspective. Besides, it has supported nearly 9,000 businesses and created 11,554 jobs until 2014. Moreover, Beneficiaries reported that they had improved socio-economic status and living conditions. And they increased their knowledge about HIV and corrected their risky sexual behavior, all of which reduces their vulnerability to HIV (Southern African Development Community, undated). However, the program still has aspects that need to be paid attention to. First of all, it’s commendable to have collaboration between nations and interactions among government, NGOs and private sectors. However, from the national level, due to economic, political and cultural differences, some countries may not have the capacity to implement the project as expected, which, in turn, results in a less satisfying outcome. Therefore, it’s critical to build a structural coordination system, so that the program could be adjusted based on local conditions and resources could be freely mobilized and fully utilized. Secondly, the institutional capacity for coordination of informal sector activities is also very important. As a multi-party collaboration program, it needs to provide clear guidance on what each sector should do and it should think about how to attract the private sector to participate in the program. Thirdly, it’s useful to have monitor and evaluation in all aspects of project implementation, so that the project can change directions whenever it finds out a problem, which leads to a better result. Currently, the monitor and evaluation system is semi-manual, making the work laborious, slow, and time-consuming. Therefore, technology is required. A new system makes the data collection and analysis process more efficient.

Lessons are learnt from the case study of South Africa. Economic empowerment could be useful complementary strategies incorporated into current health policies. Using the economic framework, we can tackle the problem from another angle, making the total impact greater than before. Moreover, the cross-border collaboration and cooperation between institutions are encouraged. No matter what level of collaboration it is, the coordination is very important. In addition to it, different responsibilities and goals should be assigned to each participant accurately based on their own condition. Lastly, it’s a trend to apply informatics infrastructures and blockchain technology to evidence-based practices.

RESULTING POSITION

This Group expresses our support for actions to promote cross-government collaborations, cross-sector collaborations within governments, and to assemble and sustain strategic long-term partnerships creating communities of practice among professionals across disciplines.

POLICY ACTION RECOMMENDATIONS

Our policy action recommendations based on the literature, case studies reviewed, lectures by experts, and conversations with them are delineated below:

- Binational Collaborations are a strong tool to promote the health of vulnerable populations including immigrants and refugees. However, trust and capacity building are necessary elements to promote the sustainability and effectiveness of complex collaborations.

a. Trust and commitment at a local level is instrumental. The success of the implementation of a surveillance system and sharing of information by the USMBHC was possible due to the effort invested in relationship building and commitment of individuals and organizations involved to the achievement ofestablished goals. As a result of the activities implemented through strategic planning, research, and academic-community partnerships, other important organizations, such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Pan American Health Organization have contributed to the sustainability of the USMBHC by providing support and funding.

b. The active implementation and assessment of methods of community engagement to mobilize communities to participate in initiatives to improve their own health is of utmost importance to sustain binational collaborations. The literature reviewed included examples of successful community-academic partnerships including the efforts exerted to improve collaboration and relationship building through capacity building.

c. It is absolutely necessary to implement principles that will remove barriers to sustainable collaborations. Principles have been devised, implemented in a variety of forms, and refined. We strongly encourage the use of practices delineated in the literature to promote trust, true collaboration, and power sharing (Israel, Eng, Schulz, & Parker, 2013; Wallerstein, et al., 2020).

- There is a need to strengthen the health care infrastructure of immigrant receiving communities, especially in resource constrained settings and settings where the majority of health care investments go to disease treatment and cure rather than prevention. For example, the U.S.-Mexico border has an already fragile health care infrastructure that risks collapse if additional strains are imposed. The initiatives described in the case studies can strengthen the health care infrastructure of immigrant receiving communities and include:

a. Community health workers are another form of strengthening the health care infrastructure and provide services and advocacy to change social determinants of health. The incorporation of CHWs into the health care workforce is fully endorsed by the World Health Organization’s Alma-Ata Declaration.

b. Advocacy for the rapid training and incorporation of immigrant health care professionals through block chaining is a promising strategy. As argued above, coalitions can set in place actions to facilitate the adoption of this initiative.

c. Training health care workers on immigrant-informed care, an initiative that can build upon trauma-informed care, can bring awareness to practicing health care providers who may interact with immigrants about their specific needs. Furthermore, it can promote the will to implement specific screening practices and facilitate collaborations across sectors to bring needed services. According to the literature reviewed, coalitions are also a mechanism to spark change in this domain.

- Identifying and addressing health issues from an economic perspective can attract the investment of different sectors and increase intersectoral collaborations to change a fundamental social determinant of health.

a. Economic empowerment can be integrated into existing policies protecting and improving migrant’s health rights. A better financial status helps migrants improve their living conditions. Furthermore, it increases their chances of visiting a doctor and getting in-time medical treatment, all of which reduce their vulnerability to certain diseases.

b. The economic empowerment program must be sustainable. The effect of only providing funding to small enterprises is short-lived in nature. And thus, programs should combine funding with business and financial skills training, not only giving participants enough capital to start the business but also developing their entrepreneurship abilities to run the business in the long term.

- Intersectoral collaboration is a key element for achieving the policy goal. The efforts from the private sector are especially meaningful. Therefore, policymakers should create economic incentives such as microcredit with a low-interest rate and business subsidies, encouraging enterprises to work with other institutions and make contributions to protecting migrants’ health. Actions taken by companies include raising salaries, improving the working environment, providing private insurance, and delivering health education to workers.

- The implementation and management process should incorporate the application of technology. A better-automated monitor and evaluation system- a larger space to store data, a stronger capability to deal with data, supports the development of the program. Furthermore, devising a collaborative agreement for data sharing that will abide by the laws of respective countries can facilitate data sharing.

CONCLUSION

The consequences of failure to promote collaborations across governments, strengthening the health care workforce, and promoting intersectoral collaborations to promote the health and well-being of immigrants and refugees can be dire. Consequences are multi-level and include human rights violations, loss of economic power, increases in crime and violence, and other conditions that exacerbate substance use and infectious disease rates, and collapse of health care systems. Unfortunately many barriers prevent implementation of collaborations, however, the literature we discussed and the specific case studies illustrate that with political will creative ways of promoting collaboration are possible.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Arvey, S. R., & Fernandez, M. E. (2012). Identifying the core elements of effective community health worker programs: a research agenda. American Journal of Public Health, 102(9), 1633–1637.

Brown, L. D., Chilenski, S. M., Ramos, R., Gallegos, N., & Feinberg, M. (2016). Community prevention coalition context and capacity assessment: Comparing the United States and Mexico. Health Education & Behavior, 43(2), 145-155.

Casillas R., R. (2006). Una vida discreta, fugaz y anónima; los transmigrantes centroamericanos en México. Recuperado el 5 de septiembre de 2016, de Centro de Documentación sobre Migraciones para América Latina, Organización Internacional para las Migraciones: http://cimal.iom.int/es/authors/rodolfo-casillas-r

Findley, S., & Matos, S. (2015). Bridging the gap: How community health workers promote the health of immigrants. London: Oxford University Press.

Forster-Cox, S., Torres, E., Adams, F. (2018). Essential roles of Promotores de Salud on the U.S.-Mexico Border: A U.S.-Mexico border health perspective. Global Journal of health Education and Promotion, 18(1), s4-s18.

Franco Sanchez, L. M., & Granados Alcantar, J. A. (2019). Características de la migración internacional en la actualidad en Mexico. Universidad Autónoma de Mexico. Accesses at ru.iiec.unam.mx/2-032-Franco-Granados.pdf on June 2, 2020.

International Labour Organization. (n.d.). Economic Empowerment and HIV Vulnerability Reduction Along Transport Corridors in Southern Africa. Retrieved June 8, 2020, from www.ilo.org/africa/countries-covered/index.htm

Israel, B. A., Eng, E., Schulz, A. J., & Parker, E. A. (2013). Methods for Community-Based Participatory Research (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Josey-Bass.

Karanja, R., et al. (2019). Blockchain-based digital ID platform for Refugee camps in Kenya. World Economic Forum.

Klinger, D. E. (2020). Migration and Immigration. Public Integrity, 1-5.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2017). The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Nicholas, P. K., Mfono, N., Corless, I. B., Davis, S. M., O’Brien, E., Padua, J., . . . Fortinsky, S. (2016). HIV vulnerability in migrant populations in southern africa: Sociological, cultural, health-related, and human-rights perspectives. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 5, 1-8. doi:10.1016/j.ijans.2016.09.003

Radford. M. & Krogstad, R. (2019). Recently arrived U.S. immigrants, growing in number, differ from long-term residents. Pew Research Center. Accessed at www.pewresearch.org/recently-arrived-u-s-immigrants-growing/ on May 27, 2020.

Red de Coaliciones Comunitarias (2020). Network of Community Coalitions. Alliance for Border Collaboratives accessed at http://www.coaliciones.org/es/publicaciones

Saadi, A., Cheffers, M. L., Taira, B., et al. (2017). Building immigration-informed, cross-sector coalitions: findings from the Los Angeles County Health Equity for Immigrants Summit, 3(1), Health Equity, 431-435.

Southern African Development Community. (n.d: A Prevention & Health Promotion Initiative. Available at www.borderhealth.org, accessed 5/20/20.

Southern African Development Community. (n.d.). Innovative HIV Prevention Practices and Programmes for Long Distance Truck Drivers and Sex Workers: Global Lessons and Opportunities in the SADC Region. Retrieved June 8,2020, from www.msh.org/sadc_fact_sheet_dec_4_2015_jp_final.pdf

Torres, S., Balcazar, H., Rosenthal, L. E., et al. (2017). Community health workers in Canada and the US: Working from the margins to address health equity. Critical Public Health, 27(5), 533-540.

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment status of the foreign-born and native-born populations by selected characteristics, 2017-2018 annual averages,” Table 1, www.bls.gov/news.release/forbrn.t01.htm. Data are for people ages 16 and over.

Velasco, J. L. (2013). U.S.-Mexico Border Health Commission Initiatives and Activities. Voices of Mexico, 98, 1-6

Wallerstein, N., et al. (2020). Engage for equity: A long-term study of community-based participatory research and community-engaged research practices and outcomes. Health Education & Behavior, 47(3), 380-390.

World Health Organization . (2020). Refugee and Immigrant Health.

WHO. (2018). Health of Refugees and Migrants. Retrieved June 8, 2020, from www.who.int/AFRO-report.pdf?ua=1