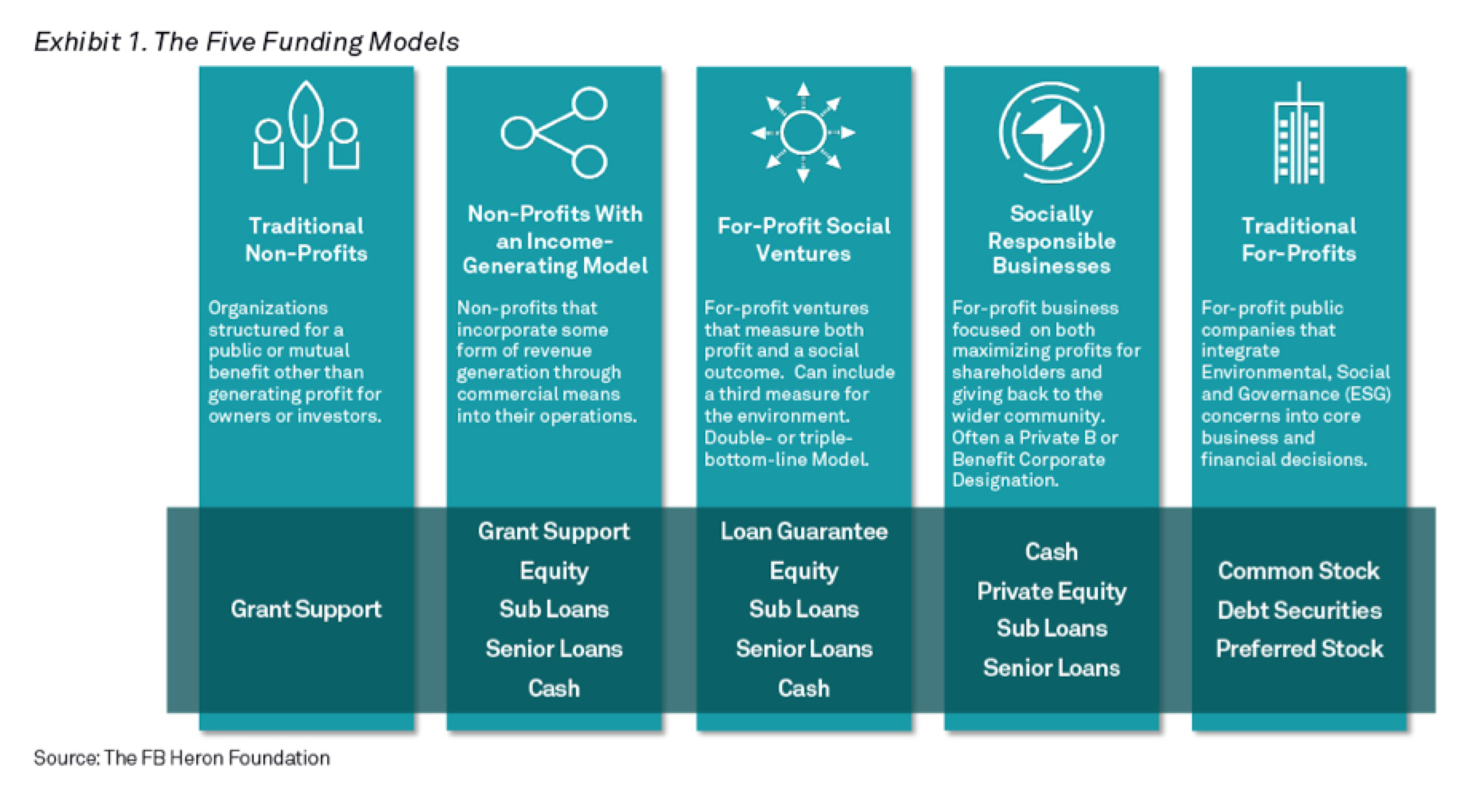

In "From Philanthropy to Social Investment: A New Way of Giving," I discussed how the emergence of new philanthropic funding models allows strategic philanthropists to have a greater impact on the causes they care about most. Alongside traditional non-profits, these newer models -- income-generating non-profits; for-profit social ventures; socially responsible businesses; and carefully screened, traditional for-profit businesses -- form an ecosystem that provides multiple ways of addressing a single problem. (Sophisticated philanthropists, like Bloomberg Philanthropies, often partner with the government to solve key issues, as well.)

In many respects, these five models are similar to investment asset classes, each with their own specific role to play. Just as no single asset class can provide the growth or asset protection necessary in a well-constructed investment portfolio, no one funding model can fully address the various complexities of a systemic social issue like homelessness, illiteracy, or protecting the environment.

As in investing, donors are wise to construct a diversified "philanthropic portfolio" that utilizes these models to varying degrees in accordance with their long-term philanthropic and wealth goals. Doing so can help donors move beyond simply addressing the symptoms of a social issue to get at the deeper root causes.

Developing a Framework

In order to build an effective philanthropic portfolio, a donor must first understand the strengths of each funding model, their unique applications, and the differences between them.

The best way to illustrate this is to frame it in terms of a particular issue. Take homelessness, for example. A typical donor who is concerned about homelessness likely donates to traditional non-profit organizations, such as shelters, soup kitchens, and food pantries. Organizations like these provide vital and necessary services to those struggling with homelessness, but they are primarily focused on addressing the symptoms of homelessness -- not its root causes. It's only one piece of a very large, complicated puzzle.

For a donor interested in addressing the totality of homelessness and not merely its immediate effects, a broader approach is needed. Looking at the larger issue, the donor might identify a number of smaller issues that must be addressed to effectively combat homelessness: a lack of affordable housing, a poor job market, a lack of access to educational opportunities, or affordable daycare. A multifaceted problem requires a multifaceted solution.

While designing such a solution might seem daunting, it's simpler than it may first appear. The key to this process is remembering that it is iterative. Donors should take a phased approach that starts small and gradually evolves into a full-fledged philanthropic portfolio that suits both the issue at hand and the donor's circumstances.

Start Simple and Be Strategic

Donors shouldn't feel compelled to jump in headfirst and start funding all five types of models immediately. Instead, they should choose the most familiar areas, which can serve as a foundation for the addition of more complex or advanced models down the road.

For most people, this will likely mean funding traditional and income-generating non-profits, as well as making selective investments in for-profit companies.

For example, a donor beginning to put together a philanthropic portfolio aimed at addressing homelessness might start by funding non-profit homeless shelters in their area and loaning money to an income-generating non-profit that operates a low-cost health care clinic for economically disadvantaged people or a job placement agency.

They may also wish to recalibrate their investment portfolio to ensure they are not investing in traditional for-profit companies that may be exacerbating the problem they wish to solve -- for example, a financial institution that engages in predatory lending.

These first steps represent an entrée to the more advanced models, namely, for-profit social ventures and socially responsible businesses.

Profit for a Purpose

It can sometimes be hard to distinguish between for-profit social ventures and socially responsible businesses, as they have a lot in common. However, the distinction is important.

Essentially, a for-profit social venture is a business that makes a particular social outcome -- say, addressing homelessness -- the centerpiece of its efforts. For example, Find Edmonton is a Canadian furniture company that sells furniture to consumers at a profit, and then uses those profits to provide furniture to people who are just emerging from homelessness free of charge. The profit motive and the charitable motive are one and the same. These ventures are sometimes referred to as double- or triple-bottom-line businesses, as they measure themselves not only on fiscal performance, but also on their social and/or environmental impact.

For a socially responsible business, profit is still the main motive. However, these businesses make an effort to ensure that their pursuit of profit takes social welfare into account. Fig Loans, a Houston, Texas-based company, offers installment loans for low-income Americans who might otherwise need to rely on predatory payday loans. Fig Loans makes little to no money on the loans themselves; instead, they provide a fair price on small loans up to $800. This allows the recipient to manage a financial crisis without resorting to predatory lenders and repay the loan in the shortest amount of time available. By partnering with non-profit organizations, Fig Loans earns profit by building up their customers' credit scores over time and then referring them to traditional banks. Rather than taking advantage of a vulnerable group of people in pursuit of profit, their business model incentivizes them to better the lives of their customers.

Fig Loans, like many socially responsible businesses, is a certified "B Corporation," which is a private certification that tracks and measures how effective a company is at achieving its social and environmental goals. The certification is administered by a non-profit organization, B Lab.

Organizations such as these need more direct help and involvement than those in the other categories. Donors may want to co-sign a line of credit or make a direct investment in return for equity in order to provide these ventures with the capital needed to get off the ground.

Identifying the Right Funding Vehicle

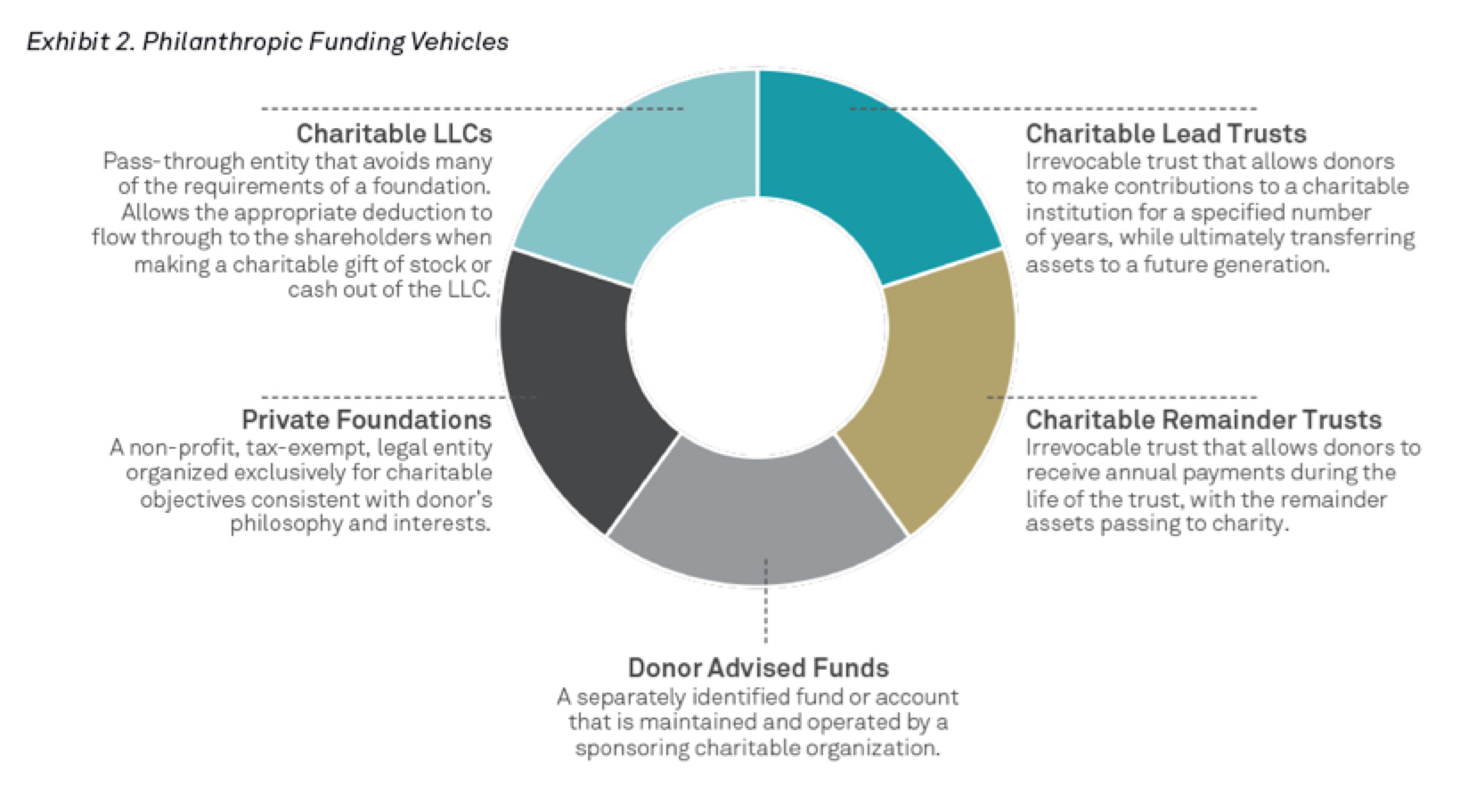

Once donors determine what they want to fund with their philanthropic portfolio, they must then determine the right vehicles to carry out the funding. There are several options:

Each of these vehicles can be useful to donors interested in funding the ecosystem, though donor advised funds, private foundations and charitable LLCs offer the most flexibility. Charitable LLCs are perhaps the most flexible, as donors can take the income tax charitable deduction when they distribute from the LLC, rather than when they fund it, as is the case with a donor advised fund.

Ultimately, each of these vehicles can be invested according to a specific, values-based mandate set out by the donor. Utilizing multiple vehicles and aligning each with a specific funding goal within the ecosystem, known as "stacking," can be particularly effective.

Conclusion

While tackling large social issues and causes can be daunting, the framework that donors develop around these new funding models offers a greater sense of control and accomplishment. By recognizing the complexity of these issues, donors can confront each facet of their chosen issue with a purpose-specific tool that can make the overall mission seem less overwhelming.

In the end, finding meaning and purpose in how wealth is deployed for philanthropic ends is a balancing act, and the "philanthropic portfolio" approach is one method that donors can use to find that balance.

The views expressed herein are those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect the views of BNY Mellon. The content hereof is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment, legal, tax, or financial advice.