The world is at war with a virus, one to a scale never seen before, but America has a secret weapon.

Once again, we are witnessing America’s silent health care army mobilizing to fill the gaps that plague this country. Even before the pandemic was officially declared, this workforce of nearly 450,000 medical professionals was already taking aim and planning its’ response to an invisible and unpredictable enemy. This is not their first fight either. Just as this silent workforce mobilized in the face of the floods in Texas or the fires in California. From every natural disaster to the refugee crises here and abroad. From the front lines of the opioid crises to the ever-enduring gaps of patient knowledge. America’s Nurse Practitioners (NPs) and Physician Assistants (PAs) continue their work, quietly filling our nation’s health care gaps and bringing us one step closer to a day in which every single American has access to affordable and high-quality care.

Now if only it was legal for them to do this all time…

Stories are being told every day of the brave men and women serving in our hospitals and clinics, but the NPs and PAs of America are arguably our most under-appreciated health care workforce. This is even more true today, as this workforce is being called to action in ways we have never seen before. In the face of a pandemic, these medical professionals are mobilizing everywhere to combat the spread of this virus and ease our National health care burden. There are close to 300,000 NPs1 and around 125,000 PA2 in America. They are highly qualified, certified medical professionals who have within their training, the ability to lower healthcare costs, increase accessibility, reduce ER wait times, and improve the overall health outcomes of Americans everywhere.

“He was a patient who was displaced by Hurricane Harvey. He described for me vague symptoms of fatigue and dizziness and brushed it off as being related to his chronic conditions of high blood pressure. When I detected his low heart rate, I insisted he go to the hospital, he argued with me but ultimately agreed to go.

Later that day, when I called the hospital and learned he never presented, I called my patient back. He told me that he had been waiting in the waiting room for so long that he decided to leave. I pleaded with him to go back and try again; he was hesitant to agree at first, but after some convincing he finally agreed to go back.

He had a third-degree heart blockage and immediately underwent procedures for coronary artery stents.”

– NP testimonial (anonymous for patient confidentiality)

In fact, you would be hard-pressed to find an issue in health care that would not at least be eased by the improved utilization of Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants. This is, unfortunately only half of the story; as it stands, not a single presidential candidate has mentioned these providers in all of their debates and health care policy proposals. Moreover, more than half of the states in the U.S. still refuse these providers the practice authority they need to deliver the care they are trained to provide. This is perhaps America’s biggest overlooked solution to her health care woes.

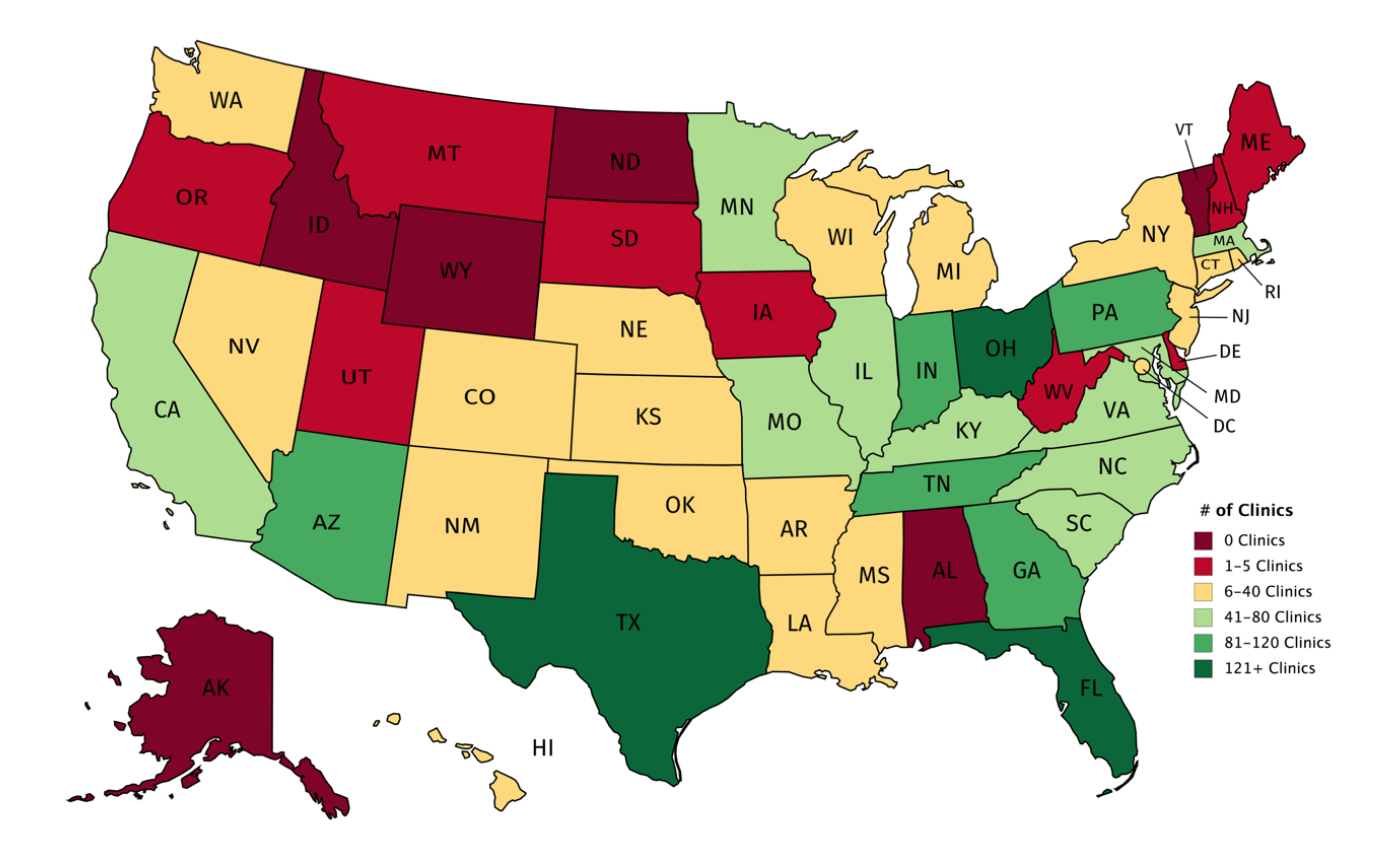

A close examination of America’s health care system will quickly reveal that NPs and PAs currently work in virtually every health care touchpoint. It is in Convenient Care Clinics (CCCs) however, where these providers take a leading role. CCCs are health care facilities located in high-traffic retail outlets with adjacent pharmacies that provide affordable and accessible care to consumers who otherwise would have to wait for appointments with a traditional Primary Care Physician or Provider (PCP). CCCs in this way provide a promising health care option that complements traditional medical service providers. For context, 60 percent of the patients seen in CCCs do not have a primary care provider. All CCC clinicians have advanced education in providing quality health care for common episodic ailments including cold/flu, rashes/skin irritation, and muscle strains or sprains as well as a number of chronic conditions. CCC clinicians also provide immunizations, physicals, and preventive health screenings. This is America’s most affordable and accessible health care touchpoint with more than 40 percent of the U.S. now living within a 10-minute drive of these clinics.

While some have viewed the expansion of these clinics as a major asset and have since established collaborations and networks of referrals, the expansion of these clinics has also brought rivals. There are parts of the health care community, that to this day, oppose laws that will allow more of these clinics to expand and succeed. The most often used tactics for preventing the expansion of convenient care clinics, is through the defense of restrictive practice authority for NPs and PAs.

In restrictive states, laws require career-long supervision and delegation or team management by another health provider in order for the NP to provide patient care3. States with reduced practice laws that lessen restrictions can still require career-long collaborative practice agreements with a supervising physician. Many states (28 in total) still restrict or reduce practice authority in areas such as medical staff membership, primary care provider designation, the ability to independently prescribe Schedule II drugs, the ability to order physical therapy, the ability to sign a death certificate, and end of life care.

These state laws and licensure agreements are defended by claims that NPs or PAs are not qualified to deliver the care that they are currently providing for more than 50 million patients each year. As one might expect, these claims are tacitly false, and for the sake of ensuring greater health care for all, as a country we must oppose these claims. In fact, 22 states and the District of Columbia, citing the incredible health care outcomes of allowing NPs and PAs to practice at the top of their license, have already begun allowing “full-practice authority.”

You can learn more about them here.

“She was 22 years old. When she came into my clinic, she asked that I change her antibiotic because it wasn’t working. I remember her saying ‘I will make this quick because I know that you are so busy.’

I had her sit down and share her story. It turns out that I was the fourth provider that saw her. She was seen one week prior and treated for bronchitis with a z-pack and inhaler. I made her think back to when exactly these symptoms started. She recalled going to her primary care provider (PCP) in August and being diagnosed with allergies. She admitted that she never felt like her cough went away. I continued to ask questions which lead to her admitting to always feeling full, mild exertional dyspnea, chronic dry cough, and fatigue. We weighed her and there was a 20lb weight difference from when she saw her PCP in August.

She didn’t put the symptoms together as she was excited and thought the stress of college was making her lose weight. Her history kept sending major signals. When I performed her assessment, she had diminished breath sounds on one side.

I decided to report her to the emergency room. Within hours, she was transferred to a larger facility. She had a large pulmonary mass that was impeding her ability to breathe. She was diagnosed with Stage 2 Lymphoma and immediately underwent lifesaving treatment.”

– NP testimonial (anonymous for patient confidentiality)

Examining what constitutes the training and expertise of these providers quickly reveals that NPs and PAs hold advanced professional degrees and obtain years of high-level training at the masters or doctoral level. NPs typically after a four-year bachelor of science of nursing program, pursue rigorous master of science in nursing (MSN) or doctor of nursing practice (DNP) programs that signal a high-level of mastery and training. Likewise, physician assistant programs typically require at least six years of rigorous education and training. Both NPs and PAs must pass a series of licensing exams at the state and national level, as well as participate in continuing education programs. These advanced medical professionals are underutilized experts in 28 states, based on their training standards alone. Moreover, these tend to be the states with the greatest need for more advanced medical professionals.

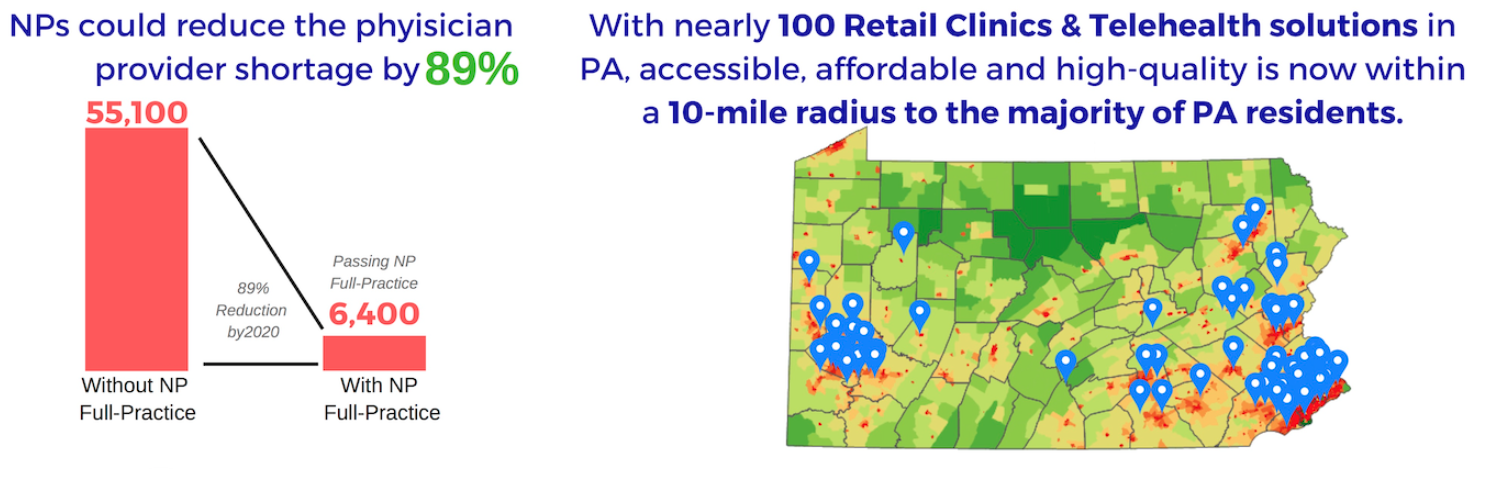

Provider shortages have increasingly become one of the more prominent issues discussed in national health care reform. As of today, more than half of states are already experiencing a shortage of licensed professionals; there simply are not enough physicians to meet demand. By 2025, the US Health Resources and Services Administration estimates that this shortage will increase to 72 percent of states not having enough licensed providers.4 This shortage will mean higher wait times, reduced access to care, and an overall decrease in the health outcomes of Americans, which will only further exacerbate the issue. Fortunately, these provider shortages do not take into account the impact of fully utilizing NPs and PAs. Taking Pennsylvania as an example (a particularly restrictive state), the introduction of full-practice authority would almost instantly reduce provider shortages by up to 89 percent. Moreover, CCCs are already spread throughout the state to meet the unique demands of the state:

As for quality concerns, NPs and PAs are held to incredibly high standards, and it shows.

Research consistently reflects that NPs provide care that is comparable in quality to physician care5. CCC healthcare professionals use evidence-based protocols that adhere to established clinical practice guidelines and regulations6. That is perhaps why their quality scores and the rates of preventive care offered are similar for convenient care clinics as for other delivery settings7. CCC had a 92.72 percent compliance with quality measures for appropriate testing of children with pharyngitis vs HEDIS average of 74.7 percent; they also had an 88.35 percent compliance score for appropriate testing of children with URI vs HEDIS average of 83.5 percent8. Perhaps most striking of all, is that providers working in CCCs consistently have a patient satisfaction rate above 90 percent.

The presence of a CCC is the presence of an accessible, affordable, and high-quality healthcare touchpoint. Moreover, for the local hospital, physician, or specialty care office, CCCs can actually serve as an access point for finding new patients in need of care.

“A week ago, a young woman came into our store with a sore throat; she was looking for a strep test. After talking to her and learning she was 33 weeks pregnant, I took her blood pressure and seeing it was 200/146, my alarm bells went off; I knew this woman was in danger. I got her onto the exam table, telling her to lie on her left side, and I called 911.

Last night, she stopped by the store again, and I barely recognized her, she had lost so much fluid weight.

She told me the rest of her story. She had developed a pulmonary edema and had been coughing up blood. Her baby was having a fetal heart attack. Within an hour and a half of leaving my clinic, she delivered a 2Ib 13 oz baby. As she told me this, her mother came to her side, and looking at me through tears in her eyes, choked out the words, ‘you saved my daughter and her baby’s life.’”

– NP testimonial (anonymous for patient confidentiality)

Already clinics have taken up new roles in providing COVID-19 testing and care, they begun coordination with the CDC to fill in the gaps for Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) testing, and dermatology. They are coordinating to expand care to everyone from children to the elderly, to our teachers and veterans.

We as a country have the opportunity to make this job easier for our NPs and PAs. You can join this movement by calling your local state representatives and urging them to lift restrictions on practice authority to permit NPs and PAs to provide the care that they are trained to provide.

Together, we can provide the accessible, affordable and high-quality care all people deserve.

Author bios

The Convenient Care Association (CCA) is the international trade association of companies and health care systems that provide consumers with accessible, affordable, quality health care in retail-based locations. CCA works primarily to enhance and sustain the growth of the Convenient Care industry through sharing of best practices and common standards of operation.

Nathan (Nate) Bronstein, MPA, MsED, MSSP serves as the Chief Operating Officer of the Convenient Care Association. Nate works in direct coordination with the executive leadership from all of the major retail health clinic operators in the United States, Canada, and Mexico, as well as more than 40 health care companies and thousands of Nurse Practitioners, Physician Assistants, and Pharmacists across the country. Nate is a former science teacher and policy wonk turned public health and education entrepreneur. He has participated in more than 26 incubators and accelerators focused on process design, implementation, and organizational change, leading to more than six-years consulting with clients ranging from individual entrepreneurs to for-profit and non-profit companies, as well as government agencies. His work is heavily focused on population health initiatives and includes improving health plans, finding and supporting new health care technologies, supporting providers, and consulting with government officials at both the state and federal level. Nate has written for the Chronicle of Social Change, consults with young entrepreneurs and nonprofit organizations through the Social Innovations Journal and currently serves on the board of Philadelphia's oldest and largest music school. He holds two bachelor’s degrees from American University in Washington D.C., as well as three master’s degrees in education, public administration, and the science of social policy from the University of Pennsylvania.

Michael (Mike) Clark, MPA serves as the Policy Director for the Convenient Care Association. He has researched, published, and worked in the areas of collective impact, financial innovation, impact investing, and social/policy entrepreneurship. He has played a variety of social sector roles including executive leadership positions in the nonprofit sector, public policy and legislative entrepreneurship, and K-12 education administration. Mike’s experience includes serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in Bulgaria. He holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Scranton, and a master of public administration from the University of Pennsylvania’s Fels Institute of Government.

Work Cited

1 https://www.aanp.org/about/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet

2 https://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.pdf

3 https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/state/state-practice-environment

4 https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/.pdf

5 Mundinger, Mary. “Primary Care Outcomes in Patients Treated by Nurse Practitioners or Physicians,” JAMA, 2000.

6 Jacoby, Richard, Albert G. Crawford, et al. “Quality of Care for 2 Common Pediatric Conditions Treated by Convenient Care Providers.” American Journal of Medical Quality. 2010.

7 Mehrotra, Ateev, Llu Hangsheng, John L. Adams, et al. “Comparing Costs and Quality of Care at Retail Clinics with that of Other Medical Settings for 3 Common Illness

8 Jacoby, Richard, Albert G. Crawford, et al. “Quality of Care for 2 Common Pediatric Conditions Treated by Convenient Care Providers.” American Journal of Medical Quality. 2010