As the social sector continues its consolidation, the already challenging work of measuring and managing social impact for nonprofit organizations grows only more difficult. Many nonprofits now manage a growing array of business lines, each with its own unique social impact measurement challenges. And while the capacity for evaluation and assessment grows with the size of an organization, the funding community’s sometimes myopic focus on support only for direct services means the critical task of measuring and improving social impact is wildly under-resourced.

At JEVS Human Services in Philadelphia, we have been working in the last few years to increase our qualitative and quantitative social impact assessment capabilities. With more than 30 programs spanning multiple domains that range from behavioral health and recovery services to a career and technical trades school, JEVS in many ways exemplifies the challenges of social impact measurement.

In this brief, I will review our qualitative social impact assessment work and suggest the unfinished work that remains.

Program Portfolio Reviews -- A Qualitative Approach

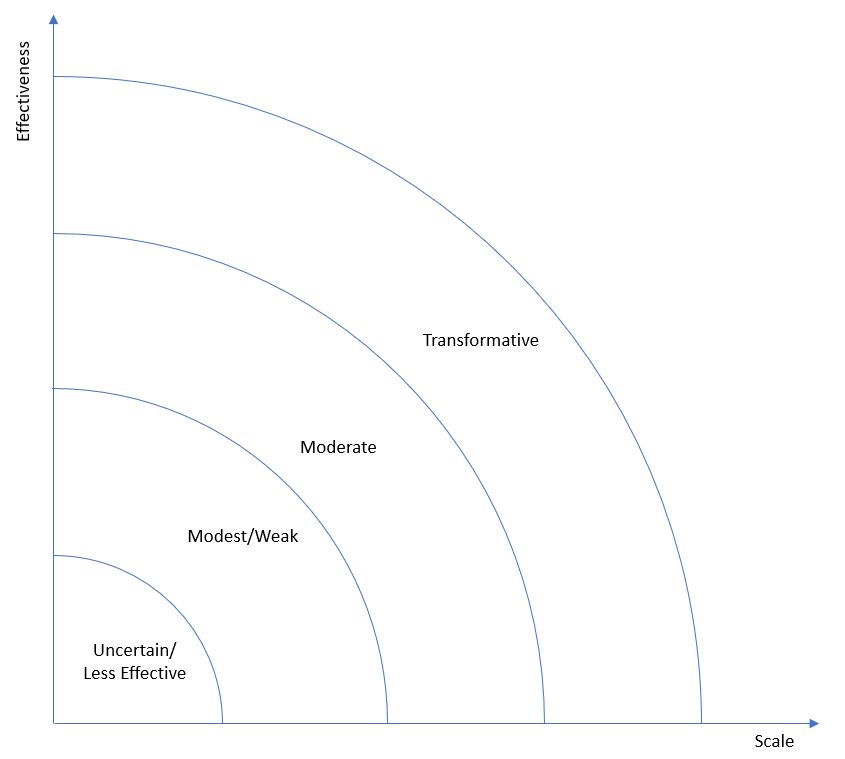

We began our assessment of social impact at JEVS with a simple supposition: that social impact can be represented across our programs by the intersection of effectiveness and scale. While a small-scale program may only touch a handful of people, the degree of effectiveness of the program for the people it touches -- and their families and communities -- could still make that program highly impactful. Conversely, a program which is only moderately effective, but which serves hundreds or thousands of people, may also be said to be impactful. This is not to negate the imperative in either case for growth or improvement, but it does provide a tool for thinking about how to assess over all impact of any given program.

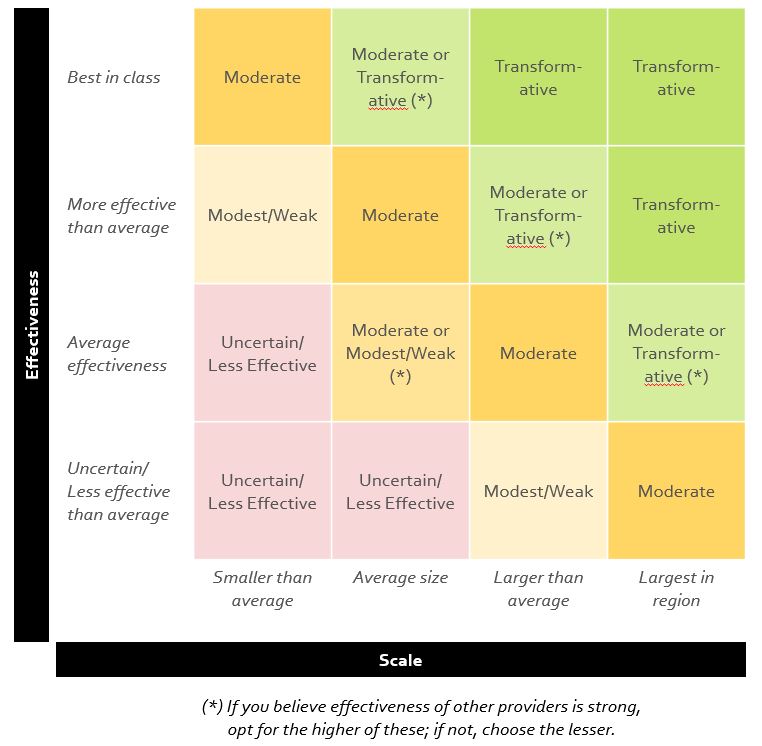

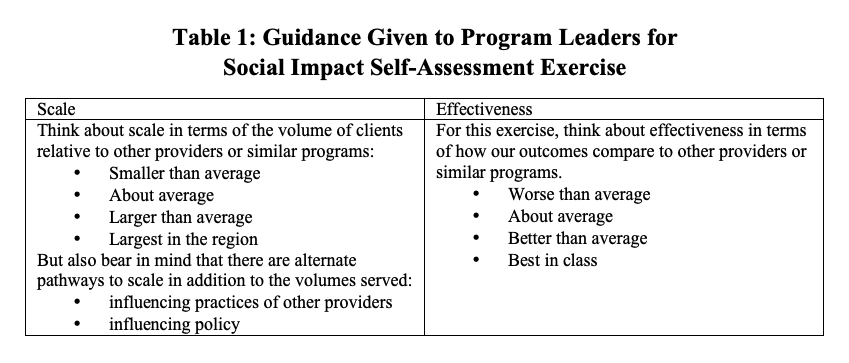

We then asked ourselves: What are simple ways to assess scale and effectiveness -- in an exercise that could be completed in a timely way without a lot of new resources. So, in a half-day session with our program leaders, we asked program managers to self-assess their programs on both dimensions.

Our experience was that most program managers knew perfectly well how their programs stood up next to other providers. Program size was often self-evident. As for the more nebulous idea of effectiveness, we gave some guidance to help with this self-assessment -- suggesting each manager reflect on:

- Whether they tended to lose participants to other, more effective programs or did they see participants transferring in from other, less effective programs;

- Whether the program tended to win funding competitions more or less often than other providers;

- The sentiment of conversations with funders, policymakers, or analysts who work with many providers; and

- Any benchmarking or comparative statistics available comparing similar programs.

Putting the idea of scale and effectiveness together, we created a rough grid to categorize each of JEVS’ programs. The grid, of course, was imperfect. Sometimes, we found ourselves measuring effectiveness against other program operators who we thought were weak. Being better did not necessarily mean we were more “effective.” We also found this exercise was less helpful for our newer programs. Nevertheless, a common nomenclature for how we think about measuring the social impact of each of our programs created a basis for charting continuous improvement needs for a program and overall strategy as an organization.

Mapping for Strategy and Planning

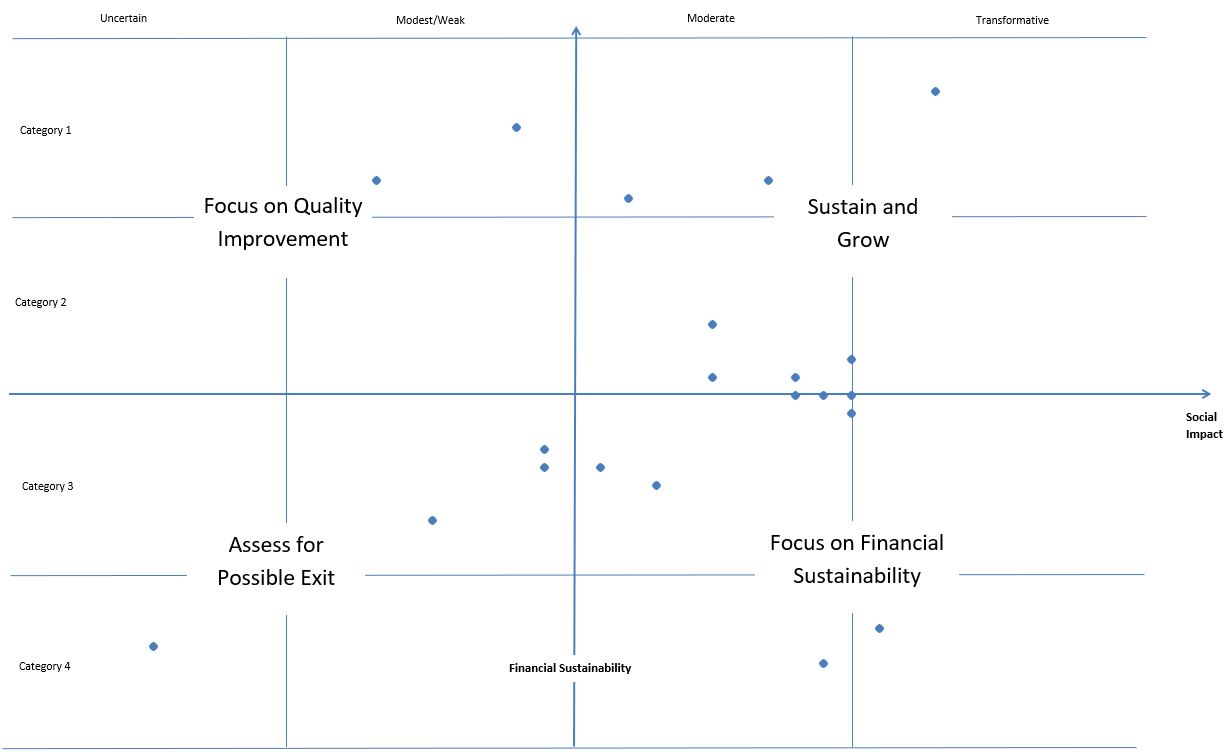

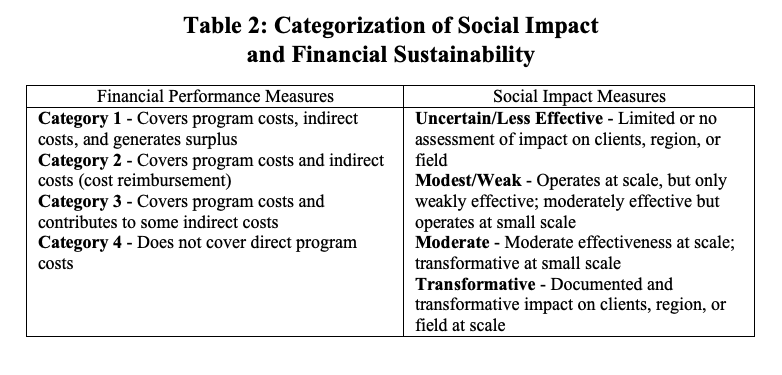

The last piece of this exercise was to map social impact of a program against its financial performance using a standard of categorization in use at JEVS.

The resulting four-quadrant analysis below suggested a way for JEVS to understand its program performance as a whole -- with each dot representing a program. Importantly, JEVS was interested not just in the current assessment, but also where programs projected they might be in three years in terms of social impact and financial performance as well as the activities and resources over that period that would be necessary to achieve that outcome. The thought exercise yielded insights into needed program organizational capacities, financial investment needs, external relationship building and the like.

Chart: Sample Plot of Programs against Social Impact and Financial Performance Metrics

For example, most programs cited a need for stronger financial analysis and marketing/outreach functions along with investments in business development and information technology as critical to realizing their ambitions for improved social impact and financial performance. These findings have led the organization to develop a three-year internal investment strategy to build organizational and program capacities in these and other areas.

Connecting to Quantitative and Third-Party Assessment

A frequent criticism of qualitative social impact assessment regimes is that they lack rigor. Theories of change, sentiment analysis, formative assessment, and qualitative self-assessments like the one described here seem insufficient. We view this work as part of a larger body of work on social impact assessment that includes a system of key performance indicators that allow us to track monthly social impact measures and an on-going and systematic engagement of third-party evaluators that provides periodic assessments of programs using both formative or summative methods. Ultimately, JEVS seeks a social impact assessment capacity that allows us to engage in continuous improvement of individual programs and management of our portfolio of programs for ever-higher standards of performance.