Summary

Ashoka launched the field of social entrepreneurship in 1980, and today it is the largest global association of social entrepreneurs. This article provides an overview for the journal issue that focuses on insights from Ashoka’s Global Impact Study of its network of social entrepreneurs with the following 10 articles ranging from regional, gender, sector, and subject matter analyses. Over the last decade, new technologies have enabled transformations in communications, media, and financial systems that have accelerated the pace of change and radically opened new means for citizen participation. In this context, social entrepreneurship has become a globally recognized practice, welcoming corporate, university, and government participation in the movement previously dominated by the nonprofit and philanthropic sectors. This article summarizes pioneering insights of Ashoka that serve as the foundation for the field, and it updates our thinking on the impact of our Fellows based on evidence from our most comprehensive survey of our global network of 3,500 social entrepreneurs in 92 countries. These data confirm the core framework for Ashoka's current vision of realizing an Everyone a Changemaker world.

Social Entrepreneurship is Transformative: Scaling it to Address New Challenges Requires an Everyone a Changemaker world

By any measure, the idea of social entrepreneurship as a way to spread effective social change for the good of all, and to address the world’s most pressing problems, has been successful. It is not an overstatement to say that, since Bill Drayton coined the phrase in the early 1980’s, social entrepreneurship as a movement has been deeply influential in philanthropy, academia, major global corporations, government, and other institutions. Consider:

- Entire publications such as this journal and Stanford Social Innovation Review, among others, are devoted to social entrepreneurs’ solutions that are working. The New York Times’ weekly on-line column “Fixes” by David Bornstein, and the organization he founded, Solutions Journalism, continue to engage journalists and practitioners to report on systems-changing solutions that are working to move the needle on previously entrenched social problems. And social entrepreneurs themselves are writing books each year to tell their inspiring stories of how change happens.

- Governments are looking to social entrepreneurs for new policy ideas and for transformational leadership. In the United States, we saw the establishment of the White House Office of Social Innovation and the Social Innovation Fund. In the European Union the Social Impact Fund was created, and the United Kingdom led the way in the developing the concept of social impact bonds.

- The World Economic Forum and the Skoll World Forum regularly feature social entrepreneurs and their ideas. More corporate CEOs are finding that working with social entrepreneurs and young changemakers fuels their ability to see the future differently (See Mourot in this issue.)

- In the last 15 years, universities have moved from offering courses in social entrepreneurship and innovation to degree programs and Centers of Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship. In addition, university presidents, provosts, and donors understand that these programs offer critical opportunities to prepare the next generation of leaders. Students gain a competitive edge in participating in these offerings, and universities are adding them as a means to recruit the best and brightest.

- Finally, the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Mohammed Yunus has been followed by subsequent Nobel awards to Malala Yousafzai and Kailash Satyarthi in 2014 -- all three social entrepreneurs with systems-changing ideas. Many other prizes, including the MacArthur, Goldman Environmental Prize, Skoll, Echoing Green, and Schwab all feature social entrepreneurs. Foundations large and small, including MasterCard, Gates, Ford, MacArthur, and Rockefeller, have all given awards or grants to social entrepreneurs.

Early on Ashoka estimated that only one in 10 million individuals has a systems-changing vision and the lifetime personal commitment to realize that vision. Meanwhile, the rate of change in the world is simply increasing too fast for the relatively few numbers of social entrepreneurs to tackle alone the challenges we are facing and the ones we will be facing soon. The old world is crumbling, and we need to quickly retool for what is coming. Rapid technological change, in creating mistrust of our national and global institutions, fraying (and in many cases tearing) of the postwar consensus on overarching social values such as tolerance, rule of law, liberalism, and even truth itself, the exponential rise of artificial intelligence, ethnic, and other nationalisms -- not to mention the growing existential threat to the human race of climate change -- will soon create a world characterized by a “new inequality.” The long-standing inequalities of wealth, race, gender, geography, education, and social status will persist, but they will be overlaid by a new inequality between individuals, institutions, communities, and nations that have the ability to drive the changes that are coming and those that will be steamrollered over by it. If we under-stand its dimensions and seize the opportunities it creates, this new framework can be a vital tool for addressing these long-standing inequalities in a transformative way.

Therefore, we need to build the specific skillset of every individual to be able to function in a world of constant change, what Ashoka calls the Everyone a Changemaker world -- a world where every young person masters the skills of empathy, leadership, teamwork, and changemaking, and where every individual has the ability to identify social problems and create positive change.

In the pages that follow, we glean key insights and themes that have emerged based on the experience of Ashoka Fellows, our network of social entrepreneurs, over the past 40 years. The articles in this volume plumb the data gathered in an extensive study comprised of survey and interviews conducted by Ashoka over the past several months and validated by LUISS University in Rome. The results present a rich portrait of the ways in which Ashoka Fellows have learned what it takes to thrive and succeed in rapidly changing contexts. More importantly, the data show us how they act as role models to inspire others to see that change is possible, and how they grow others’ changemaking skills by offering a myriad of roles for many more to participate in the change process.

Social entrepreneurs are the critical ingredient in the changemaking ecosystem. Their experience and their example are precisely what informs the conclusion that we need to build an Everyone a Changemaker world. In every field and geographic context, their innovations chart the how-to steps for stakeholders ranging from policymakers to social activists and university faculty. Their continued participation is vital to achieving that goal and once again to help us see what comes next. Accordingly, I want to focus briefly on Ashoka’s history and the evolution of our movement to further set the context for the results of this study.

Building the Field of Social Entrepreneurship

Social entrepreneurs are the driving force of Ashoka’s past, present, and future. Yet, their role in Ashoka’s journey has evolved over time. Ashoka’s pathway for building the social entrepreneur-ship movement is comprised of four main stages. In the first stage, in the 1980’s, Ashoka focused on defining the qualities of truly leading social entrepreneurs and proving the concept that investing in them was an efficient way to generate large-scale impact. At the time, the term “social entrepreneur” did not even exist in the public lexicon. Ashoka demonstrated with example after example that social entrepreneurs have existed across history, cultures, and geography, and therefore that the concept had resonance globally. The name “social entrepreneur” offered an identity and the community we call “The Ashoka Fellowship” -- the world’s first professional association of social entrepreneurs -- was designed to support these individuals’ ability to persist in their changemaking for the good of all.1 It is in this stage that Greg Dees pioneered the academic field first at Yale School of Management then with the first known course on social entrepreneurship at Harvard Business School. Dees later launched the Center at Stanford Business School and then the Center for Social Entrepreneurship at Duke Business School in 2001. In this same period Jed Emerson began writing on social enterprise, a different endeavor. Even today social enterprise gets confused with social entrepreneurship -- see Ganz, et al 2018.2 (Osberg and Martin’s article from 20073 is the definitive discussion which Zakaras adds to in his 2018 response to Ganz,’ et al.4 Zakaras agrees with Ganz that social enterprise is not necessarily social change, then makes the important distinction that social entrepreneurship is not the same as social enterprise.)

In the second stage, new proven solutions created demand for new philanthropic models to spread what works. Ashoka’s work inspired other organizations and investors. In the 1990’s, Ashoka spread from its initial work in South and Southeast Asia to Latin America, Africa, and Central Europe. We shared our learning with Echoing Green, Omidyar, Skoll, and Schwab, all of whom were looking for highly leveraged ways to invest in big change. They, along with others, listened and added enormous fuel to the movement in the form of ideas, funding, and visibility through numerous collaborations and touch points with Ashoka’s team, its Fellows, and its broader network contributing to an ecosystem of support for social entrepreneurs. This phase of knowledge sharing spurred a kind of “wholesale” replication of the concept of social entrepreneurship where many organizations began independently replicating both financial and non-financial support to social entrepreneurs. Within Ashoka’s network, it was very early 1990 that we first recognized how social entrepreneurs were offering new roles to young people and others as changemakers5 and that doing so was key to spreading their ideas and social change efforts. And we built ties to the Corporate sector to bring added resources and ideas, as well as to expose this sector to the commitment and creativity of social entrepreneurs.

By the early to mid-2000’s, stage three was underway. We continued to expand geographically to new regions including Western Europe and the Middle East. Social entrepreneurship as a field was catapulted into a new level of awareness in the world by David Bornstein’s seminal book, How to Change the World, which featured the work of Ashoka and many of its Fellows and has been translated into more than 30 languages. Ashoka’s recognition that our social entrepreneurs offer roles to young people and others to grow their changemaking muscles inspired Ashoka to launch our Youth Venture and Changemakers competitions as new ways to spread these ideas globally with partners on multiple continents and representing a wide variety of fields. And new geographies brought new innovations to our network that then spread globally. For instance, the Ashoka Support Network founded by an Ashoka staff member in the United Kingdom now has members from around the global who engage directly with social entrepreneurs to support their work. And university professors and administrators asked for advice to answer demand from students asking for resources which we answered with Ashoka’s network of Changemaker Universities and Ashoka U.

By the late 2000’s, Ashoka built a robust global network of leading social entrepreneurs. Follow-ing our Fellows’ examples, Ashoka invited other changemakers to join us. We could see how social entrepreneurs practice a new style of leadership that enables everyone to lead -- that their constant iterative engagement with the people involved in the issues they seek to solve puts “beneficiaries” in the role of co-creator and collaborators. Ashoka Fellows serve not only as role models for those who want to make positive change in the world, but also actively recruit changemakers to get the work done and ensure it endures. Through the lens of our Fellows, we saw the world differently: one where each and every person has the power to drive change. And the way they do so is by practicing empathy, new leadership, teamwork, and changemaking. This is what an Everyone a Changemaker world looks like.

Today, social entrepreneurs have both a name and a recognized place in society. Ashoka’s pioneering role in building the field and creating the largest association of social entrepreneurs --Ashoka Fellows -- has directly served millions around the world. But beyond that, countless more have spread their ideas thanks to the numerous pathways Ashoka’s ideas and work has created for investors, partners, and influencers to contribute to the broader social good. In this fourth stage Ashoka continues to invest in finding and supporting a growing number of Ashoka Fellows, adding more than 100 per year and bringing them into our expanded network of change leaders. Ashoka benefits from the opportunity to constantly be looking for the cutting edge social innovations globally, with teams on the ground in 38 countries whose role is to do just this. As a result, Ashoka has a unique bird’s-eye view not of problems but solutions -- a sort of epidemiologist for solutions sets. Across fields and geographies, we see a common pattern: Social entrepreneurs close inequality gaps by cultivating changemakers to continue to advance a world in which everyone is a changemaker. (See Wells and Sankaran 2016 for examples of our social entrepreneurs employing and building these skills in their own institutions and movements).6

Measuring Impact

From its beginning Ashoka has sought to understand the what and how of its Fellows’ impact and how Ashoka can best support them and change for the good of all more broadly. In 1998, Ashoka launched a periodic study of our social entrepreneurs’ impact to see if those in our network were having the quality of impact our selection process was designed to produce. We also sought to understand what kind of impact Ashoka’s efforts had on their work. Doing so required designing a study to measure systems change. We began to track independent replication; policy change, and persistence as approximate measures of systems change and to test how our network was faring against these measures. In 2006 we published an article in ARNOVA about this re-porting system and the pattern that our findings over several years revealed.7 A lot has happened over the last two decades since we started: social entrepreneurship has become a globally recognized practice, and we have seen radical changes in new technology fueling revolutions in finance and communications-media which have accelerated the pace of change as well as enabled broad citizen participation. New sectors have joined the movement. Our own network of Fellows has more than doubled since 2006, and as a result we continue to learn about the how-to of social change across 92 countries and all fields of social need. Based on what we have learned over this time, our strategy has evolved and while consistent measures do offer an important perspective on patterns over time, our understanding of impact has also evolved as we learn what members of our network are doing.

While speaking to groups I have frequently gotten the question from skeptical audience members asking me to name one social entrepreneur who has “really scaled.” While there are similarities between the business entrepreneur and the social entrepreneur there is also a fundamental difference: The social entrepreneur is motivated to ensure that the solution is in the hands of the people who need it. For them, therefore, success is determined by idea spread, not by size of budget, staff, nor shareholder earnings.8 In our most recent study only 12 percent of those surveyed re-ported that their sole revenue was from the sale of products and services. One can imagine a radically different sized budget number needed to account for return on investment to account for all the resources expended by external entities which independently replicated the idea. My favorite example to illustrate this is Florence Nightingale. Nightingale is largely credited with creating the nursing profession, it was during her work with soldiers in the Crimean war where she recognized soldiers were dying due to infectious disease rather than wounds and introduced radical changes. Nightingale did build a nursing school but had no marketing machinery or branding crediting her with the idea; there were no shareholders whom she made wealthy. And yet her ideas around infectious disease control, hospital epidemiology, and hospice care revolutionized the medical industry and remain relevant today even in the face of radical advances in medicine and the extraordinary rapid changes in technology and social life in the last century since she left us.9

Unlike business, there still is no uniform standard for social impact. David Bonbright’s Keystone concept of “constituent voice” made an important contribution even before the technology and media revolutions which provided the rocket fuel enabling the widespread business practice of today bombarding customers with requests for customer feedback.10 Constituent voice, however, recognizes that customer feedback and program delivery satisfaction are very different from measures of long term social change which may be invisible or horribly uncomfortable for those experiencing needed changes for the good of all.

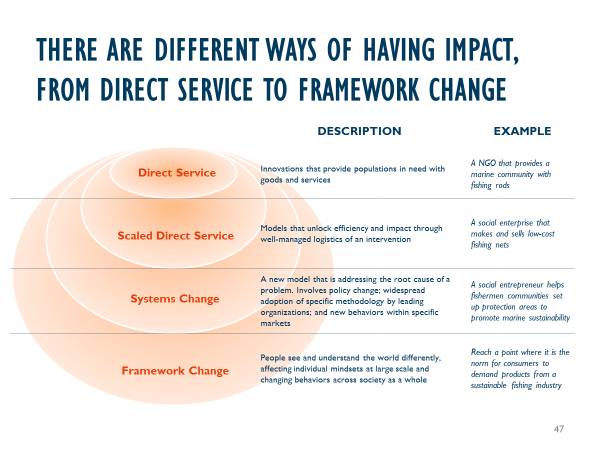

Ashoka’s latest view of impact has also sharpened and is articulated in the chart below. While many organizations in the sector expend vast resources to count direct service -- relatively few have focused on how to assess system change or framework change.11 Ashoka has been focused on system change since the 1990’s and today, also on measuring framework change.

What Does the Evidence Say?

This journal issue highlights some of the data from our global study, supporting our strategy, our programming and, I hope, the field more generally.

In 2018 more than 850 Ashoka Fellows from 74 countries took part in a Global Fellows Study designed to understand their impact as well as the role Ashoka has had in contributing to that impact. We do not know of a more diverse database of social entrepreneurs in the world.

The paragraphs which follow present a summary of some of the results; please find a more in-depth analysis of our findings in the articles to follow in this issue (referenced below).

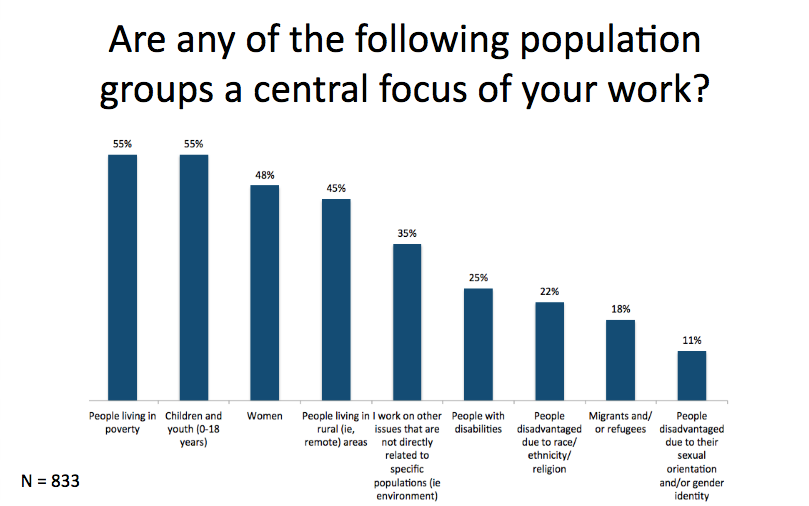

The Data Set Represents a Diverse Group of Fellows in Various Sectors and Geographies

Of the 858 responses, 42 percent were women, 57 percent were male, and one percent identified as “other gender identity.” This distribution is representative of Ashoka’s overall network. The respondents focus on a wide variety of population groups including people living in poverty (55 percent), women (48 percent), and people with disabilities (25 percent). The Fellow respondents also represented a variety of business models, with 32 percent reporting that they received no revenue from selling products or services, and 12 percent reporting that they received all of their revenue from selling products or services.

LUISS University’s article in this issue analyzed Fellows’ diverse sectors of work by geography in order to explore whether Fellows’ focus areas were aligned with the priorities set by the World Bank and other international bodies. Their robust framework is easily transferable to other organizations working in the civil society sector.

Fellows Generate Systems Change that Sticks

Ashoka’s view of system change is emergent and context-dependent. It is open to a whole array of system elements as well as how they interact -- including but not limited to public policy, industry norms, changes in market systems, building new professions, how different systems interact, etc. Ashoka learns with each social entrepreneurs’ journey not simply the issues relevant in each geography where that entrepreneur is working, but the how-to’s of strategy as well as the skills required and support needed for building leadership for deep and lasting positive change.

Our metrics to measure systems change have evolved since we first conducted this study in 1998, and include: independent replication, public policy change, market change, and shifting mind-sets. As Sara Wilf details in her article in this issue, 90 percent of Fellows report having seen their idea replicated by independent groups or institutions, 93 percent reporting having changed markets and/or public policy, and 97 percent report that their strategy focuses on mindset shift.

Systems change often necessitates many different strategies targeting a diverse array of stake-holders, demonstrated by Fellows’ reported partnerships. 86 percent of Fellows report partnering with other citizen sector organizations, 72 percent with universities, and 61 percent with for-profit companies. As Arnaud Mourot details in his article, the corporate sector is learning from Fellows’ partnerships with companies by leveraging their work to rethink business to include social benefit long term.

Ashoka is a Powerful Accelerator for Fellows’ Impact

In this study Fellows report that Ashoka has had a substantial impact on their work -- from validating their identity as a social entrepreneur, to providing mission-critical financing, in the early stages of their venture, to offering access to a global network and strategic support.

A core principle which Ashoka got right from the beginning, is the discipline of applying clear criteria to a disciplined selection process. Every Ashoka Fellow elected has passed a five-stage selection process where at each of the five stages the criteria has been met. Ashoka has never been prescriptive of the how-to’s of getting to system change nor prescriptive about the time horizon for getting there. The selection process is designed to be predictive and recognizes that big change does not happen overnight which is why we recognize that we need to assess a life time pattern of persistence. As Alessandro Valera explores in his article, ), 92 percent of Ashoka Fellows reported that the stipend helped them focus full-time on their idea and several Fellows in the interviews confirmed that this early stage funding was “mission critical.” In addition, extremely high percentages of Fellows report that Ashoka had an influence on their thinking and how they practice leadership, and perhaps most importantly, that their strategy or behavior changed as a result. All told, 84 percent of Fellows agreed that Ashoka had helped increase their impact.

Maria Clara Pinheiro and Dina Sheriff detail in their article how Ashoka creates an ecosystem of support for Fellows and our entire network of partners. Fellows in the study reported that they gained a wide variety of ecosystem supports from Ashoka staff, partners, and other Fellows -- from strategic guidance and mentorship to new funding connections and wellbeing support.

Beyond interactions with Ashoka staff, Fellows report high rates of collaboration with other Fellows and partners. This is no surprise as we have heard for decades that Ashoka’s Fellowship (the global network of Fellows) has been a key source of support in allowing social entrepreneurs to persist through times of challenge. The data shows that 74 percent of Fellows have collaborated with at least one other Fellow, with an average of four peer collaborations per Fellow globally. Reem Rahman’s article reviews Fellows’ collaboration habits through case studies and explores how collaboration is key to systems change. It also speaks to a view of leadership that builds social capital and trust.13

The Study Has Surfaced Insights That Point to New Opportunities Moving Forward

Claire Fallender and Ross Hall explore how findings from this study around Fellows’ young changemaking experiences and influences in childhood are critical to Ashoka’s LeadYoung strategy and our Everyone a Changemaker mission. We see in this data that exercising a muscle of changemaking while young lays a foundation for life. It enables young people to gain more comfort with being uncomfortable -- a critical survival skill in this rapidly changing world. With new evidence validating our strategy (such as half of surveyed Fellows report leading a changemaking initiative under the age of 21), Fallender and Hall explain the incredible opportunity to create a world in which every young person has mastered changemaking skills for the social good.

Using data from this study on Fellows’ young changemaking experiences, Michael Gordon and Sara Wilf’s article create a comparison with a non-Fellow group to examine any differences. They find that there is a substantial difference both in Fellows’ first changemaking experience and childhood influences and express the need for more research into how changemaking experiences in childhood may affect adult outcomes and achievements.

Irene Wu supplements these results with a case study on young changemaking in the East Asian context. She demonstrates how East Asian Fellows’ young changemaking experiences and strategies to promote youth changemaking in their ventures differs from Fellows in other geographies. Kenny Clewett’s article is also a case study, albeit on a new trend emerging from Fellows’ work around migration and refugees. While his case study focuses on migration in the European context, he provides recommendations and insights that can be applied in other geographies as well.

Finally, Iman Bibars’ analyzes the Fellows’ impact results by gender to identify and examine a complex web of factors that may lead to impact differences for male and female Fellows. We see social entrepreneurship has created a remarkable space for women to lead -- what other sector can boast women leading institutions they founded and pursuing ideas they authored at a rate of 40 percent? Her article is a powerful call to redefine “success” in scaling asking us to examine the merits of scaling deep.

A Note on Methodology

The 2018 Global Fellows Study used a "mixed-methods" approach which incorporated both quantitative and qualitative research methodology. Of the 50 questions in the survey 47 were close-ended, enabling a purely quantitative analysis. We piloted the survey with a small group of Fellows in April. The survey was modified according to their suggestions, and any additional questions were incorporated into the qualitative interviews. LUISS University in Rome conduct-ed an audit of our data and fully validated the data and methodology.

The online survey was available to all Fellows for five weeks from May through June 2018. It was distributed to 3,363 Fellows through a combination of automated emails from Qualtrics and Dotmailer, as well as personal communications from Ashoka staff across the globe. No survey question was a force-response, and all Fellows were given the option to remain anonymous. The survey was available in 12 languages corresponding with the linguistic diversity of Ashoka’s Fellowship. In terms of accessibility, we offered Fellows without reliable internet connection in their area or other physical constraints (such as blindness) to take the survey by phone.

Overall, the survey received 858 unique respondents (26 percent of our Fellowship population) representing input from Fellows in 74 countries. The highest response rate came from Europe, with 34 percent of their Fellows, and the lowest from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), which represents 17 percent of their Fellows. 62 percent of surveys were completed in half an hour or less, and 79 percent were completed in 1 hour or less.

43 Fellows were selected for one-hour qualitative interviews from a randomized sample of respondents to the survey. This sample was also representative in terms of gender and geographic location. The interviews were scheduled and conducted from June through August 2018.

Limitations of the study include potential selection bias, the survey emails going to Fellows’ spam, and the self-reported nature of the study. We did attempt to validate certain aspects of Fellows’ response (such as policy/legislative change) and verified the authenticity of any outlier response to numerical questions. In order to determine the extent of any potential “extreme opinion” bias we ran a test comparing Fellows who responded to the survey in the beginning and the end of the distribution period. We found no significant difference in these two groups’ opinions towards Ashoka in the survey, and concluded that extreme opinion bias was likely not an influencing factor in survey response.

Conclusion

It is increasingly clear that governments, corporations, philanthropy, and individual citizens alone cannot solve the world’s most pressing problems. In a world where the rate of change is ever increasing, we need more people with big ideas and the tools and competencies to work effectively across fields and sectors to realize answers together. Ashoka finds our social entrepreneurs and the patterns across our broad network to be predictive of future trends charting a path-way to where the world is going. Ashoka sees a new generation of young people who want to create change for good as part of their professional lives. 40 years ago, this professional pathway simply did not exist. It took Ashoka years to develop a way to find and bring to light those entrepreneurial innovators who were putting positive impact for the good of all before everything else. By definition, these social entrepreneurs were living the problem so deeply that they came to understand both the systems driving the problem and the key levers to solve it. And they were perceived by many, including their own families, to be either crazy, dangerous, or both. And in many countries today, this is still the case.

In those early years of building the profession, these systems-changing social entrepreneurs were the vanguards for social change. Not because of an idea alone but in the way they achieved their impact. When looking at the network of Ashoka Fellows in aggregate, Ashoka sees that what matters most in how well and how far impact is achieved is not the size of one’s budget, nor the number of those directly served. Rather it is idea spread: how many people are collectively en-gaged in achieving that impact through independent replication of the ideas, insights, and how to’s. Success in terms of impact also hinges on how well these social entrepreneurs attract and build teams with other entrepreneurial or intrapreneurial leaders across sectors. In other words, the most effective social entrepreneurs are those whose models help everyone be problem-solvers. This is the insight which has led to Everyone a Changemaker and enabled Ashoka to develop a road map to getting there.

Even in just the last decade, the world has shifted significantly. The rapid pace of change and the level of connectivity across geographies and diverse groups is unparalleled. Fellows continue to deeply live the problems they address and in order to succeed in big change they must have earned the trust from the communities they serve. Through Ashoka Fellows, Ashoka now has a deeper understanding of what it takes for people to lead and thrive in a world where so much change is happening. Ashoka sees that being able to understand the emotional state of another person (empathy) and change behavior as a result is critical to functioning in a team that is not governed simply by hierarchy and rules. The recipe for success includes practicing empathy and experience working in teams in which all are empowered. Leadership in Ashoka’s Everyone a Changemaker World requires recognizing and enabling agency directed toward the good of all. It is this foundation from which people can change their own lives and the lives of those close to them from an authentic, trust-based way. Trust inspires trust and enables ordinary people to do extraordinary things.

This critical insight is what we have learned from social entrepreneurs themselves and what has guided Ashoka’s strategic shift in the last decade. However effective individual social entrepreneurs are, and however strong our movement of social entrepreneurship may be, it is not enough if we are to avoid the crisis of the new inequality. To really bring our work to scale, to truly have idea spread go viral, we need to give young people command over the changemaking skill set. As friends, parents, aunts, uncles, educators, and caregivers to young people, we can be part of the movement to change what our education systems value. Young people, whether in the U.S. or Brazil or Sri Lanka, need to know and feel what it means to co-lead teams and empower others to address a problem that they are living. They need this just as much as math and reading skills. Having this young experience as a changemaker may not mean a career as a social entrepreneur. But it will enable us to address the challenges emerging from our rapidly changing world and to close the emerging inequality gap. And we do know it is a fundamental skill for anyone to thrive, whether they are going to lead change from within business or government, teach in a classroom, discover a new cure, write computer code, travel in space, succeed as an athlete, or support a social entrepreneur’s organization. And when young people behave this way, they inspire us to do more of the same, so that together we really can realize an Everyone a Change-maker world.

This issue of the Social Innovations Journal was curated by Diana Wells, Alessandro Val-era, Sara Wilf, and Terry Donovan.

Works Cited

1 Bornstein, David. How to change the world: Social entrepreneurs and the power of new ideas. Oxford University Press, 2007.

2 Marshall Ganz, Tamara Kay and Jason Spicer. “Social Enterprise is not Social Change.” Stanford Social Innovation Review (Spring 2018).

3 Martin, Roger L., and Sally Osberg. Social entrepreneurship: The case for definition. Vol. 5. No. 2. Stanford, CA: Stanford social innovation review, 2007.

4 Zakaras, Michael. “Is Social Entrepreneurship being Misunderstood?” Medium (April 16, 2018).

5 Barone, Michael. What Does ‘change maker’ mean? Washington Examiner Magazine (July 27, 2016).

6 Wells, Diana and Supriya Sankaran. “New Paradigm for Leadership - Everyone Leads.” Next Billion (December 26, 2016).

7 Leviner, Noga and Leslie Crutchfield, Diana Wells “Understanding the Impact of Social Entrepreneurs: Ashoka’s Answer to the Challenge of Measuring Effectiveness,” Research on Social Entrepreneurship: Understanding and Contributing to an Emerging Field ARNOVA Occasional Paper Series-Volume 1, No 3) Rachel Mosher-Williams ed 2006.

8 McPhedran, Jon and Roshan Paul Scaling Social Impact When Everyone Contributes, Every-body Wins Vol 6, 2.

9 Gill, Christopher and Gillian Gill. “Nightingale in Scutari: Her Legacy Reexamined.” Clinical Infectious Diseases Vol 40: 12, July 15, 2005.

10 Proctor, Andre, and David Bonbright. "Keystone Accountability and Constituent." Harnessing the Power of Collective Learning: Feedback, accountability and constituent voice in rural development(2016): 83.

11 Meadows, Donella Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green Publishing 2008

12 Beverly Schwartz shares wonderful, in-depth case studies in:

Schwartz, Beverly. Rippling: How social entrepreneurs spread innovation throughout the world. John Wiley & Sons, 2012. See also: Crutchfield, Leslie R. How Change Happens: Why Some Social Movements Succeed While Others Don't. John Wiley & Sons, 2018; Martin, Roger and Sally Osberg Getting Beyond Better: How Social Entrepreneurship Works. Harvard Business Review Press 2015;

13 For more on this see Praskier, Ryzard and Andrzej Nowak Social Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice Cambridge University Press 201.

Author bio

As President of Ashoka for the last twelve years, Diana Wells has led Ashoka's global expansion and significant increase in the number of Fellows, helping to shape overall strategy and operations. She implemented one of the first standard assessment tools for systems change impact. Ms. Wells has a Ph.D in anthropolgy from NYU, and she was named a Fulbright and a Woodrow Wilson Scholar. She received a BA from Brown University, where she now serves as a Trustee of the Brown Corporation.