Summary

The advance of desertification is seen as a threat to both productive activities and the quality of life of agricultural communities in Northern Chile. This challenge involves new ways of capturing water resources that contribute to promoting sustainable development strategies for the communities.

Based on a technology transfer experience in the Coquimbo region, the purpose is to illustrate a systemic approach based on social innovation that allows us to broaden the traditional perspective that has positioned technology as the critical node from which socio-environmental issues have been addressed. Also, extend it to all actors of the local ecosystem, empowering communities in order to generate dialogue between scientific and local knowledge, this through a process of co-production of knowledge which grants sustainability to the models of community development.

First Challenge: Towards a Two-Way Perspective of Territorial Fieldwork

While walking by his small pepper plantation and struggling to survive, one of the members of the community comments with a nostalgic voice, "the desert is lurking." As a result of the effects of climate change, water scarcity is one of the main challenges facing the north of the country. Within the 17 regions that make up Chile, the IV region of Coquimbo, is located on the border that separates the Atacama Desert with the central zone of the country.

In this region, agriculture and livestock are not only key sectors for economic development but they also represent traditional ways of life as part of their intangible heritage. At a social level, the community grows old, starting from the rural-urban migration of young people in search of economic opportunities.

Furthermore, 80 percent of the country's agricultural communities are concentrated here. These groupings of collective owners of rural land have had great difficulties in achieving prosperous and sustainable development paths, for example, 92 percent of their members are below the poverty line (Regional Government of Coquimbo, 2011).

To achieve sustainable development of agricultural communities, promoting new strategies to access water resources is required. The key is not the incorporation of new technologies only, but the effective process of technology transfer that responds to the social needs of these communities, favoring social cohesion and communities’ empowerment. That is, broadening the consciousness with which water scarcity has been addressed, understanding that it is a socio-environmental issue, where the relationships between actors is a key factor.

From a social innovation perspective, the existing dynamics in the social fields embedded in each territory are essential (Boudieu, 1994); understanding these territories as a relational and historical space, where the process of technology transfer takes place. From this perspective, the transfer is bidirectional. Knowledge emerges from the convergence between local experiential knowledge and scientific-technological development.

Therefore, it is essential to catalyze the empowerment of communities by enabling processes of co-production of knowledge from the adjustment of participatory designs and social technologies that enable dialogue between actors. In other words, the empowerment of communities allows us to advance in new ways of addressing socio-environmental challenges, respecting, valuing, and incorporating the knowledge of local communities.

This approach to this challenge does not necessarily allow us to arrive at solutions such as those usually designed by technical experts. The biggest challenge lies in being able to address those emergent and unexpected issues by facing co-creation processes and in the need of reaching multiple and constant agreements. Moreover, there is always an important quota of uncertainty as part of any process of knowledge co-production that also needs to be welcome.

The contribution of this particular project allows us to explore and analyze particular aspects of the bi-directionality of scientific-technological transfer processes to address complex issues of rural communities.

Second Challenge: A Social Dimension of Technology Transfer

The fog catcher is a system of water collection from the mist, a mass of air composed of tiny droplets of water, that, because of their weight, do not drop into the floor, but remain suspended at the mercy of the wind. For collecting them, high altitude areas close to the coast are required, likewise, the north of Chile has wide geographical conditions for the use of this eco-friendly technology. Despite this, this technology is not very powerful in the country.

It is estimated that the Coquimbo region has at least 40,000 hectares ideal for harvesting misty water. However, the main weakness is the organization of the beneficiaries who need to operate and maintain the system (Cereceda, 2014). Faced with one of these components in the region in almost a decade, there are some factors that have affected the sustainability of the project such as the difficulty in understanding the technology, the coordination in the maintenance and, in some cases, thefts of the structures (De la Lastra, 2002).

The technology requires not only to be understood theoretically by the community, it is required to be able to accommodate it in the space of everyday life. It requires incorporating new forms, new processes, and responsibilities that technology implies, in what they do. Furthermore, friendly practices and accompaniment in the process are also needed, to break down the barriers that make technology somehow strange for local communities. Generating changes that improve their usability, which can alleviate pain and situations that the community identifies as problematic.

Furthermore, the technological transfer can be a tool for sustainable development strategies for local communities if a participative approach from a logic of the co-production of knowledge is adopted. It is necessary to reflect on if the community feels part of the technological solution that was given to their problem? Enabling processes where their expertise on the territory, all the experiential knowledge they have, can dialogue with scientific knowledge and be part of the solution. Using their capacity of organization, their own models of governance give sustainability to the transfer process. These dimensions are what are at stake when we seek the empowerment of communities.

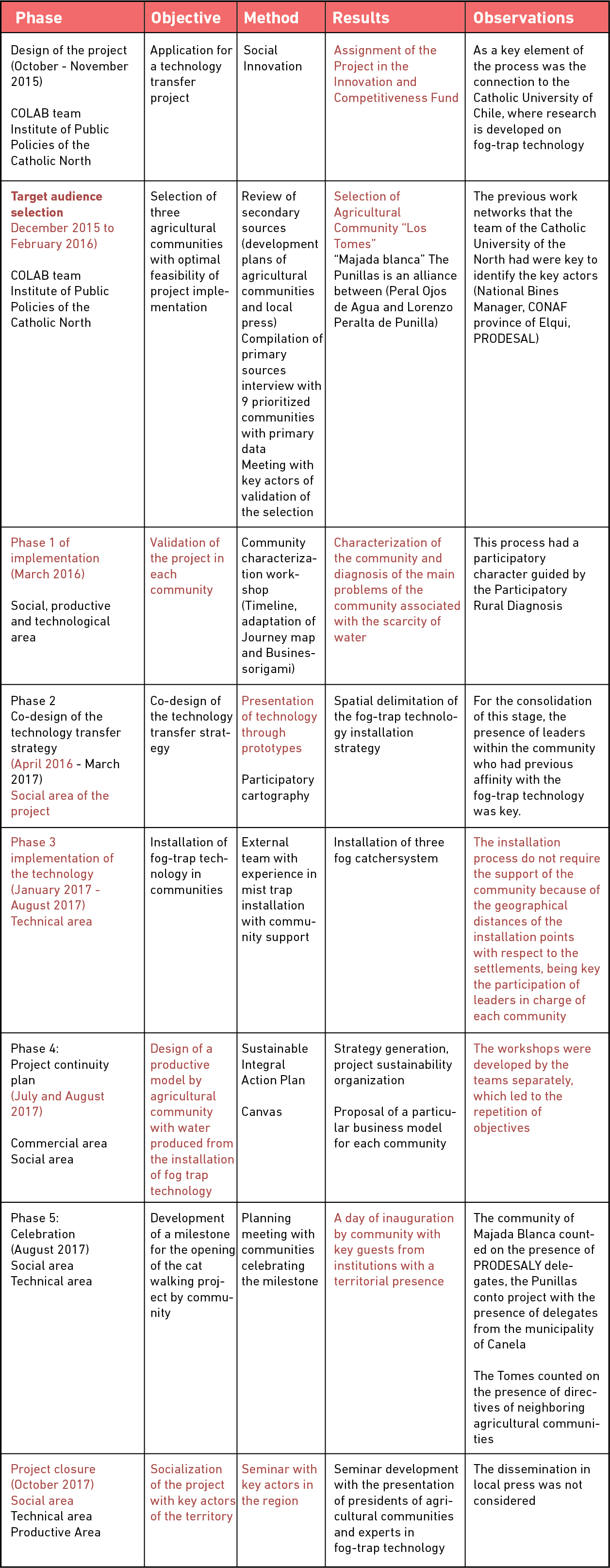

To understand this point, the project addressed (Annex 1) three work dimensions: productive, technical, and social. The first, seeks to develop along with the community a business model that is sustainable and responds to the particularities of each territory. The second seeks to adapt the fog catcher technology to the needs of the community, and finally, the social dimension of the project aims at bridging the technical-scientific and local knowledge, promoting territorial empowerment.

Also for promoting territorial empowerment, we need to place as a principle the collaboration, helping the communities to articulate and work together with the different sectors of the territories. Alongside this is a challenge to design and think of the development of the territories, to consider as a fundamental basis the articulation between actors, going beyond the sectorial work, since, to achieve the development of the territories it is key to transcend the individual interests and the sectoral diagnoses require synergies to provide complex responses to complex problems.

Third Challenge: Learning to Observe through Social Innovation Lenses

Addressing complex issues requires complex approaches (Scharmer, 2007). Otto Scharmer raises the U theory as a framework to understand those responses that arise from an emerging new paradigm. This project is based on what the author defines as a co-initiation stage. In the case of the project analyzed, different sectors summoned by the FIC project (University, Civil Society, Government) come along with the objective of addressing the challenge of desertification in Coquimbo region.

After this, in order to favor a co-sensing process, various data collection methods were carried out. Analyses of press documentation on agricultural communities, development plans generated by public and private agencies, and multiple semi-structured interviews were done as part of the process. Thus, facilitating an in-depth exploration of the diverse actors that could be involved and the particular context of the project.

One key dimension of this initiative as is related to the intense and regular fieldwork. While there, the daily dynamics of communities was shared, consequently, meetings with the agricultural communities’ directors were generated. Aiming at witnessing, in other words, connecting with the origin of inspiration and will, a time of individual reflection was introduced in the dynamics so that each actor that composed the motor group could develop the process of "letting go" all the non-essential stuff. Standing out as the value of team interdisciplinarity, meetings were generated for the design of the first prototype in one of the selected agricultural communities.

In addition, the experts in the territory met with the Regional Government to validate the prototypes proposed, these instances can be seen as a co-creation process. To conclude the project, joint reflection sessions were held, gathered by the university in their facilities in seminar formats where the community members who led the project in their communities could reflect together with scientific experts, local authorities, and students from the project-related faculties.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B13j73FdS9TJZEtiMlI4NU1SVlE/view?usp=sharing

Conclusion

Understanding technology transfer as a bidirectional process, allows the exploring of co-production dynamics, validating that knowledge that emerges from these interactions between different social actors. This inclusion of all the actors of any territory makes it possible to move, in turn, towards systemic approaches in order to address the urgent and complex socio-environmental challenges that we are facing today.

Besides, the technological development resulting from scientific research has the challenge of putting people at the center, enabling transfer processes that incorporate the actors, and territorial particularities. Then, focusing on people implies, among other things, favoring the understanding of the communities and moving towards processes of appropriation of the technological solution that has been co-created. Moreover, this social dimension of the transfer process allows for the validation of local knowledge, the empowerment of communities, and the sustainability of technology as a key tool in the co-construction of local development strategies.

The socio-environmental crisis turns out to be a reflection of the crisis in which the traditional models with which they work with the communities are found. In this sense, the crisis is an opportunity to shift the perspective towards territorial fieldwork while at the same time learning to observe with new lenses what is beginning to emerge.

Looking through the lens of social innovation implies not only the use of methodologies that promote participation, but also enables the possibility of generating new dynamics and processes in the development of this type of territorial projects. In fact, this involved the development of certain central elements in approaches from social innovation such as flexibility and tolerance to uncertainty. Elements that were determinants when allowing a path of emergence. Learning to observe through these lenses also allows us to leave open questions and propose different future scenarios that end up signposting strategies that could be followed by local communities on their way to development.

Annex 1: Systemization of the project "Technology transfer in the use of fog catchers, to enhance the productivity of Agricultural Communities through territorial empowerment" BIP 30404140-0 is a project funded by the Innovation Fund for Competitiveness (FIC) in the Coquimbo Region.

This project was carried out in partnership with the public policy institute of the Catholic University of the North.

Works Cited

Bourdieu, P. (1994). El campo científico. Repositorio Universidad Nacional de Quilmas. Recuperado de: ridaa.unq.edu.ar [15-12-2017]

Cereceda, P. (2014). Agua de Niebla: Nuevas tecnologías para el desarrollo sustentable en zonas áridas y semiáridas. Chile: CORFO.

De La Lastra, C. (2002). Report on the fog-collecting project in Chungungo: Assessment of the feasibility of assuring its sustainability. International Development Research Centre (IDRC), Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Recuperado de www.rexresearch.com/fog/chile.pdf

Gatica, S (2016) Innovación Social. Hacia una nueva aproximación del rol de Estado. Reflexiones. Recuperado de: www.cnid.cl

[15-12-2017]

[Chile] Gobierno Regional de Coquimbo (2011)Política regional para el desarrollo rural campesino de la Región de Coquimbo. Recuperado de: www.gorecoquimbo.cl [15-12-2017]

Scharmer, O. (2007) Abordando el punto ciego de nuestro tiempo. (Resumen Ejecutivo). Recuperado de: www.presencing.com [15-12-2017]

Author Bios

Sebastián Gatica Montero, MSc, Ph.D., Director of CoLab UC

Academic, researcher, and social entrepreneur. Sebastián has a long career studying and teaching social innovation and social entrepreneurship. In addition, he is co-founder of two social enterprises, Travolution.org and Manada Chile, two initiatives related to local communities and sustainable livelihoods strategies.

Catalina Ramírez González, MA., Territorial coordinator of the FIC Project

Catalina is a social worker, dedicated to human and community development. She has worked on different collaborative projects of intersectoral articulation.