Introduction

Decades of international development have taught us the importance of contextualization in sustainable social change. Learning from failed adoption and scaling of one-size-fits-all services, we now know the complexity of localization: while the principle seems obvious, much of the context is deeply embedded in social norms that determine the best strategy to create social change. This insight is core to Ashoka’s founding principle that the most impactful solutions come from the context in which the problems exist.

As a pioneer in the field of social entrepreneurship, for more than 40 years Ashoka has elected Fellows with a deep understanding and mastery of the density and intricacy of the systems they are trying to change. Ashoka Fellows are creating systems change through spreading their ideas and evolving organically from a local context, rather than coming in with top-down, hierarchical solutions. Today Ashoka has a diverse network of more than 3,500 leading social entrepreneurs from 92 countries. Fellows may converge in their innovative and systemic approach to solving social issues, yet their personal changemaking journeys are very much influenced by their respective societal contexts. In this case study, we will explore the context of changemaking in our Fellows’ youth years and how it helped shape their changemaking strategies later in life. Using the data collected from the 2018 Global Fellows Study, we focus specifically on Fellows from Asia.

Asian Culture and Its Impact on Young Changemaking

In order to explore young changemaking in the Asian context, we must first address important socio-cultural characteristics of the continent. Asia is the world’s largest and most populous continent. Home to 60 percent of the world’s population1, Asia is diverse in its ethnic groups, religions, and political systems. For the purpose of Ashoka’s Global Fellows Study, “Asia” in this case study represents the subcontinents of South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia.

Despite the cultural diversity and varying historical trajectories of these Asian nations, significant similarities remain in their cultural imprint, especially in the treatment and social expectations of youth. There is a strong culture of interdependence among family members in all three of the subcontinents. In general, the prime focus of social structure and individual loyalty is not to the self, but rather the family2. Combining this focus on family with a hierarchical social structure and collectivism, research has found that filial devotion, obedience to older family members, and maintaining interpersonal harmony is taught to young children as of the utmost importance3. The parenting style tends to be much more authoritarian than in the West, especially in East Asia and other Southeast Asian Confucian Heritage Cultures4. As a result, young children learn early on that conformity and deference to authority figures are positive demonstrations of social cohesion and connectedness5. Moreover, children in Asia often face immense pressure from their families to achieve academic and career success and inherit the filial duty of remittance once they begin employment6,7.

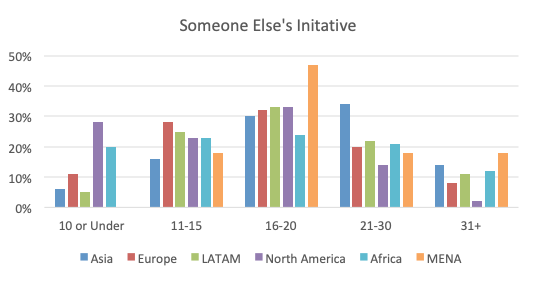

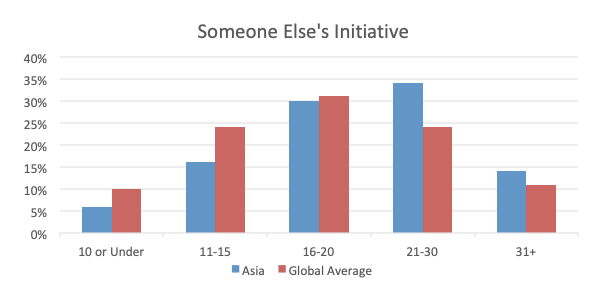

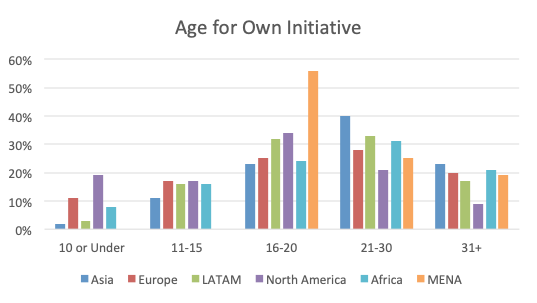

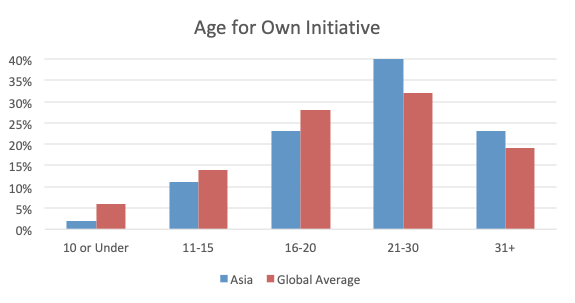

Considering all the factors above, it is no surprise that previous research has found that the level of civic engagement and changemaking tends to be low among youth in Asia compared to other regions. A 2013 global survey by Telefonica and the Financial Times, which interviewed 12,171 adult Millennials across 27 countries and six regions, found that only about 50 percent of Asian youth are civically engaged and believe that they can make a difference compared to a global average of 62 percent8. In 2018 Global Fellows Study of 858 Fellows, Asian Fellows are much less likely to start changemaking at an early age (before 21) than their peers in other regions, particularly North America and Europe. These survey results clearly demonstrate the impact of cultural context on one’s changemaking journey.

As one Ashoka Fellow from Thailand aptly summarized the common experiences of Asian youth:

“young people in their teens…the main purpose of life is to get into a university. And so, all the stories of their parents and their whole family and the teacher…it’s about getting into a good university…in the U.S. now it’s easier to get into university if you have young changemaking experience. For us, no, we’re still only according to the exam score.”

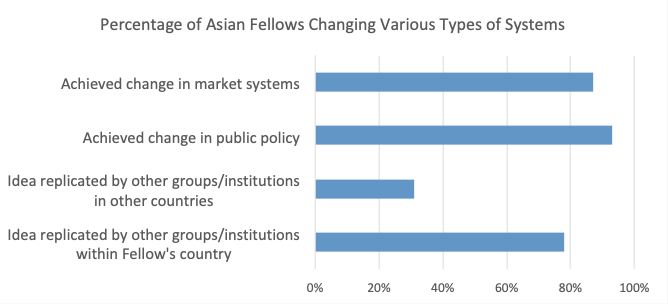

In fact, given the social environment in Asia that discourages “stepping out of line,” it is all the more significant that 23-30 percent of Asian Fellows still started leading at age 16, either through someone else’s initiative or through creating their own. And, despite a later start than their global counterparts, Asian Fellows have achieved large-scale systems change at similar or higher rates than their peers in other regions.

Ashoka believes that youth changemaking is critical to developing future social entrepreneurs (see Claire and Ross’s article or Michael Gordon’s article for a more in-depth explanation of our thinking). Yet Asian youth, due to the factors explored above and validated by our data in the Global Fellows Survey, are not given the same opportunities as their global peers.

So, how can social entrepreneurs help increase Asian youths’ agency in social changemaking?

Levers of Systems Change

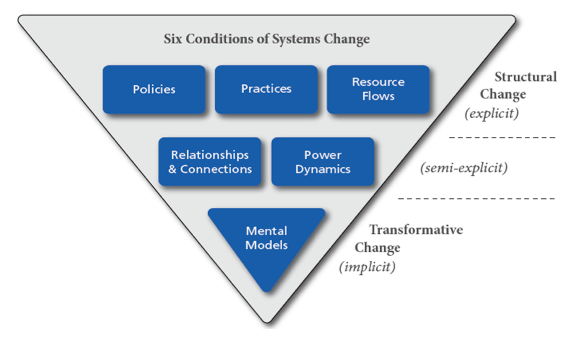

In transforming a system, one begins by identify the levers that can significantly alter the status quo. Using the framework created by Kania, Kramer, and Senge , the below graph illustrates six leverage points that can help transform a system.

Although these levers are individually powerful, they rarely function independently; most systems are formed by their dynamic interactions with each other. To put this framework into practice, we turn to examples of Ashoka Fellows in Asia who are leveraging these conditions to transform youth changemaking.

Kritaya Sreesunpagit is a Thai Fellow from 2004. Learning from her own experience and observing existing youth programs that position youth as passive and incapable of leading, Kritaya created Why I Why Foundation that supports them in designing, experimenting, and leading their own social ventures. Her approach has not only flipped the traditional youth development model upside down, it has also begun the process of transforming society’s mental model about youth agency by changing existing practices of youth programs, repositioning the relationship and connection among youth, adults, and society as co-leaders, thus reconfiguring the power dynamics between these stakeholders.

Another example comes from Yuhyun Park, a South Korean Fellow since 2013. In South Korea, where most children 13 years and younger regularly use the internet, 96 percent report having accessed pornographic content online and 38 percent have been a victim of cyberbullying. Seeing the prevalence of internet usage among young children and their susceptibility to digital risks, Yuhyun created “edutainment” across various platforms to empower young people to create digital content, responsibly conduct digital activities, and generate widespread digital behavior change. To truly give young children the agency, Yuhyun engaged youth as young as nine years old to review her content and write scripts for her platform. Her venture, Infollution Zero, has since gained traction from governments in Asia and North America to reform digital security education. What started as shifting practices, information resource flow, and relationships and connections triggered a chain reaction to transform policies and mental modes.

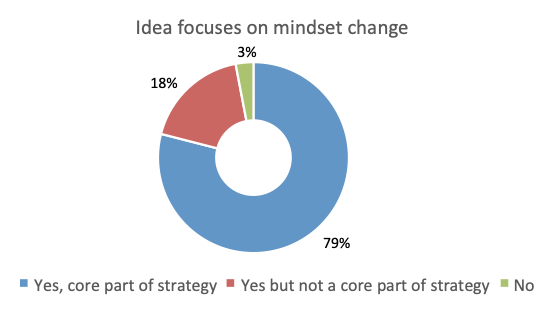

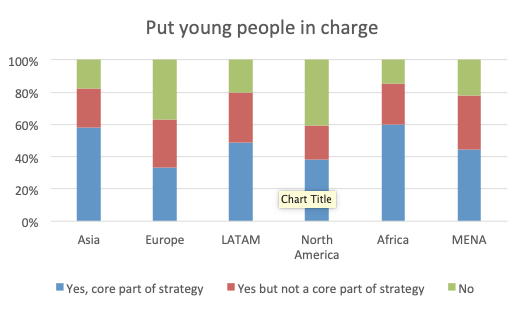

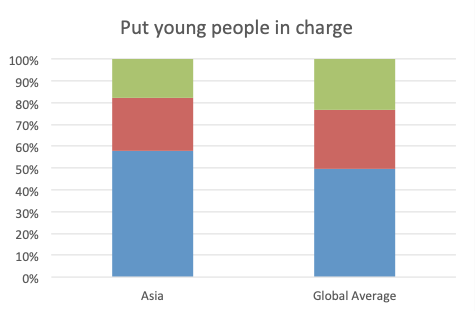

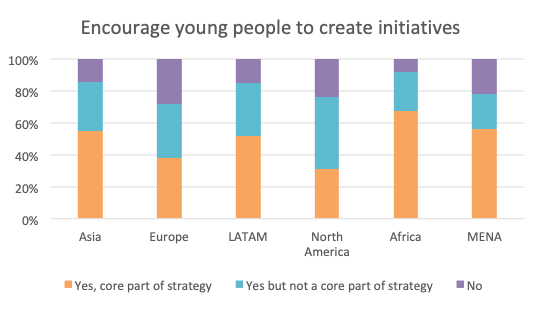

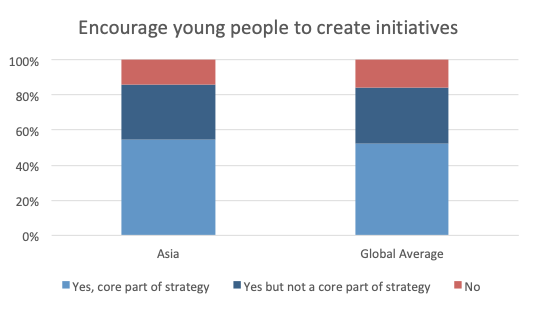

Through their work, the two Ashoka Fellows are approaching the six levers in their own ways to change the existing system about the role and agency of youth in Asia. They are hardly the anomaly: 97 percent of Ashoka Fellows from Asia reported that their work focuses on influencing societal mindset and cultural norms, 82 percent report putting young people in charge of leading initiatives within their organization is part of their strategy, and 91 percent reported that they encourage young people to create independent initiatives to spread or scale their work.

Even though their own changemaking journey began later than their global counterparts, Asian Fellows are more likely than their Western counterparts to engage and empower youth in their work. Perhaps it is precisely due to the challenge of expressing their agency in this environment, that they deeply understand that in the Asian context the most impactful strategy to change societal mindsets is to put young people in charge.

Conclusion

The force of culture and context is strong and very few people can escape it. On the other hand, it is a powerful lens through which critical insight to social solutions can be discovered. In addition to Ashoka Fellows’ efforts, globalization and technology have rendered stories of changemaking more accessible and visible to youth in other parts of the world. And the effect is beginning to take place: as the Ashoka Fellow previously quoted states: “in the last five years… it’s cooler to be in the social sector…it’s something people look up to, for young people…to volunteer at a social organizations or people starting up their own social projects.” With one young changemaker at a time, the scale will begin to tip, and one day young people everywhere will realize and act on their role as co-leaders of social change.

Works Cited

1 “Distribution of the Global Population by 2018, by continent.” The Statistics Portal. October 27, 2018. www.statista.com/statistics/

2 Robison, Richard. “The politics of ‘Asian Values’.” The Pacific Review 9, no.3 (1996): 309-327. http://dx.doi.org/.

3 Bornstein, Marc. H. Handbook of Parenting: Volume 4 Social Conditions and Applied Parenting. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers, 2002.

4 Keshavarz, Somayeh, and Baharudin, Rozumah. “Parenting Style in a Collectivist Culture of Malaysia.” European Journal of Social Sciences 10, no. 1 (October 2009): 66-73. www.researchgate.net/publication/.

5 Kim, Heejung, and Markus, Hazel Rose. “Deviance of Uniqueness, Harmony or Conformity? A Cultural Analysis.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77, no.4 (1999): 785-800

6 “India largest remittance-receiving country in the world.” The Economic Times. May 13, 2018, Access October 25, 2018, economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/finance/

7 Theis, Joachim. “Performance, Responsibility and Political Decision-Making: Child and Youth Participation in Southeast Asia, East Asia and the Pacific.” Children, Youth and Environments 17, no. 1 (2007): 1-13. www.jstor.org/stable/

8 Lim, Cheryl, and Grant, Andrew. Unleashing Youth in Asia. McKinsey Center for Government, October 2014.

Author bio

Jing Irene Wu is Change Manager, Global Venture, and Fellowship at Ashoka. Irene convenes and collaborates with Ashoka’s more than 30 country offices in identifying and supporting leading social entrepreneurs around the world. Prior to Ashoka, Irene designed and led youth social entrepreneurship programs in Asia, engaged in education policy in the U.S., and spent time in rural Kenya measuring program impact for a grassroot NGO. Irene holds a Master’s degree in International Education Policy and Management from Vanderbilt University, and is a graduate of the University of Michigan and Johns Hopkins University.

The Water of Systems Change. Boston: FSG, 2018.