Why Systems are Core to Transformative Social Change

For social entrepreneurs tackling our world’s most complex and deep-rooted challenges, creating sustainable social change can seem a herculean task. Is the initial step to target policymakers with a solution or to change how key stakeholders think about a social issue? Is it better to start local and build a model that works or to target key influencers within international bodies who can affect widespread change?

In Ashoka’s 2018 Global Fellows Study, we learned that most Ashoka Fellows’ (Fellows) response to these questions is simply “Yes.” Changing policies and mindsets often go hand-in-hand. And in order to scale a solution, Fellows usually first need to demonstrate their innovation works. For the majority of Fellows systems change is not one monolithic strategy for addressing societal challenges; rather, like chess players, Fellows are employing different, multi-step strategies and engaging every piece on the board to win the game of social change.

Ashoka first began electing Fellows -- social entrepreneurs “with a systems-changing idea” -- in 1980. Since then, a rich literature and field of study exploring systems change has developed at universities and research institutions around the world. Core to this field is the idea that social entrepreneurs must fundamentally shift an entire system in order to create long-lasting change. As social entrepreneurship researchers Gregory Dees and Paul Bloom explained, “social entrepreneurs must understand and often alter the social system that creates and sustains the problems in the first place.”1 Systems researcher Sally Osberg has termed this “equilibrium shift.”2

Measuring ‘Systems Change’ Through Idea Spread, Not Organizational Scale

Ashoka’s selection criteria have remained the same since its founding, but the metrics with which we measure Fellows’ systems change have matured considerably. This evolution is explained in Diana Wells’ 2007 article on how Ashoka tracks systems change.3 Ashoka’s core impact metrics for systems change -- independent replication, mindset shift, public policy, and market change -- mirror Fellows’ single-minded focus on spreading an idea to achieve systems change rather than achieving traditional private sector measures of “scale.” Former Ashoka employees Jon McPhedran Waitzer and Roshan Paul have written extensively about the inherent contradictions and challenges in social impact-oriented organizations adopting business scaling strategies. They argue that systems-changing social entrepreneurs “let loose a well-defined idea to create a movement or mission-aligned ecosystem, rather than only growing the organization behind it.”4

Because Fellows see “scale” in terms of how deeply an idea spreads rather than as an increase in employees or direct beneficiaries, they often pursue distinct systems strategies. Achieving “scale” means changing market systems by shifting societal narratives and how people think, rather than just what they buy. And it means challenging existing power structures to make space for everyone to be an active participant in social change. Whether Fellows’ ideas spread through open-sourcing, social franchising, licensing, training other institutions to copy their model, or strategic partnerships with government, the end result is the same. In sharp contrast to most for-profit entrepreneurs, systems-changing social entrepreneurs are willing to relinquish control and ownership of their idea in order to see it spread as far as possible.

With so many strategies to achieve systems change, not to mention Fellows’ diverse fields of work, target populations, and geographic contexts, it has been a challenge for Ashoka to develop comprehensive and inclusive metrics for systems change. As Ashoka team member Odin Mühlenbein explained in his recent article “Systems Change -- Big or Small?” systems change encompasses both “big vision” goals such as free access to clean water, as well as “targeted systems change” strategies that break the big vision down into concrete steps.5 In this study we used Ashoka’s previous work in measuring systems change as a foundation to develop more comprehensive questions to understand both “big vision” and “targeted systems change” strategies that Fellows employ.

Ashoka’s Systems Change Questions

The 2018 Global Fellows Study involved a survey of Ashoka Fellows, with 858 respondents, as well as 43 in-depth interviews for further context on Fellows’ unique systems change strategies. For an overview of the methodology used, please see Diana Wells’ article in this issue. It is notable that all systems change data was self-reported by the Fellows themselves. While we did validate reported systems change in the 43 interviews, we did not do so with all 858 respondents.

The following questions were used in the survey to measure “systems change.”

- Since becoming an Ashoka Fellow, has your idea been replicated by other groups or institutions?

- Does your idea focus on influencing societal mindsets/cultural norms?

- Since becoming an Ashoka Fellow, to what extent has your idea and work achieved change in public policy?

- Since becoming an Ashoka Fellow, to what extent has your idea achieved change in market systems?

While every Ashoka Fellow is pursuing a unique strategy to achieve systems change, broad connections appeared in the study that demonstrate how together Ashoka Fellows and the social innovation ecosystem of educators, policymakers, journalists, business partners, and others can create collective systems change. We are excited to share a “big vision” picture of how Fellows achieve systems-level impact emerging from the study and new insights that we’re learning from using a more in-depth analysis of Fellows’ systems change achievements.

Independent Replication

Ashoka Fellows know that in order to spread their idea quickly and turn it into society’s new normal, they must employ innovative strategies to get their idea into the hands of as many people as possible. Independent replication is one indicator Ashoka has consistently used to measure Fellows’ “idea spread.” We define independent replication as a partnership with another organization or institution that takes on a Fellows’ idea and brings it to even larger scale and indirect impact. Independent replication can happen through strategic partnerships, licensing, or open-sourcing, among other strategies.6 With the advent of new technologies and digital tools, it is becoming easier for social entrepreneurs to make their idea accessible and easily replicable.

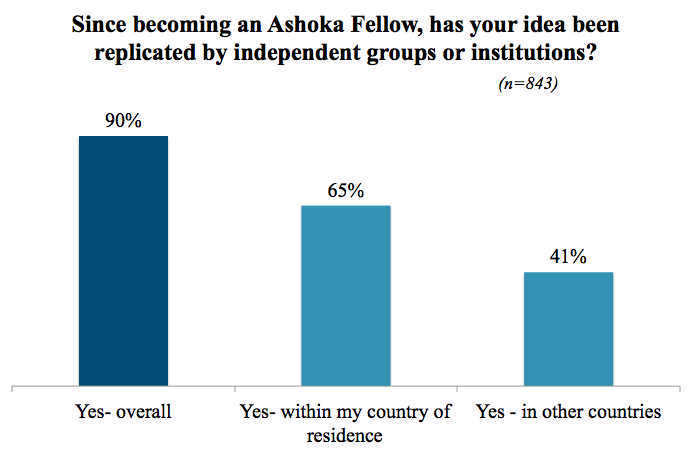

90 percent of Ashoka Fellows have seen their idea replicated by an independent group whether at an international or national level. During interviews, Fellows told us that they viewed independent replication as key to their strategy for social change, although it often took them several years of trying and failing on their own before they realized they needed to give up “control” over their idea in order to scale it.

Kritaya Sreesunpagit is a Fellow from Thailand whose story illustrates this trajectory. Kritaya’s Why I Why Foundation nurtures young leaders to articulate new ideas for social development and connects them to the resources and skills they need to bring their ideas to life. She explained that over time, she shifted from a direct service model to consciously replicating her idea through partnerships. She began training other groups and institutions in her model in order to expand across Thailand.

“Once we start working for a couple years, then we look more at like policy expansion so that we know that we can cater to the whole country or for the whole region. We want to find partners and for them to take on the ideas and adapt to whatever approach that's more suitable for the areas. So, we work with the National Innovation Council so that [our approach] could also be incorporated into their strategies, in supporting innovations.”

Mindset Shift

“Mindset shift,” also referred to as social norm change, is a key component of Fellows’ strategies for sustainable impact. Especially for Fellows working towards systems change for under-represented and marginalized groups (such as women and girls, LGBTQ people, and migrants), changing societal beliefs and acceptance towards certain behaviors is often necessary for sustainable, long-term social transformation.

In the survey, 97 percent of Fellows reported that their idea focuses on influencing societal mindsets/cultural norms. While this high data point certainly reflects a certain degree of “bias” towards selecting Fellows focusing on mindset shift, it also demonstrates that Fellows may share Ashoka’s view that mindset shift is a core strategy for systems change. The percentage of Fellows who reported that mindset shift was “core to their strategy” was particularly high in MENA and Asia.

During the interviews, we found that Fellows often employed multiple “targeted systems change” strategies to achieve mindset shift, such as empowering a marginalized group to lead while simultaneously educating and incentivizing key partners. As Czech Fellow Dagmar Doubravova knows, mindset shift in itself is not a single strategy -- in her work improving outcomes for incarcerated people, she used a multi-pronged mindset shift strategy including media campaigns, peer mentoring programs, and volunteer coaching programs in prisons by private sector leaders. Dagmar believes that without public understanding and support of criminal justice and the related debt reform, even changing legislation and developing scaling mechanisms for successful programs will not be enough for systems change

“The first goal [in mindset shift] was that we were able to cooperate with the media, so if they call us and ask for some stories, we are ready to prepare our clients so that they are able to share their stories positively. The second is community centers where we have organized many activities for the public, but behind these activities and gardening center are also our clients. So, people can see our clients in other situations and change their own attitudes. It's good for everybody if we give a second chance to people with a criminal past.”

Policy Change

The term “policy change,” often brings to mind the most well-known end result: legislation. Indeed, new or modified legislation can have widespread and long-term social impact -- for instance, due in large part to Fellow Akkai Padmashali’s tireless advocacy for transgender rights, Karnataka state in India has passed the first civil rights bill for transgender individuals that will impact an estimated 400,000 people in the state with legal protections from discrimination.

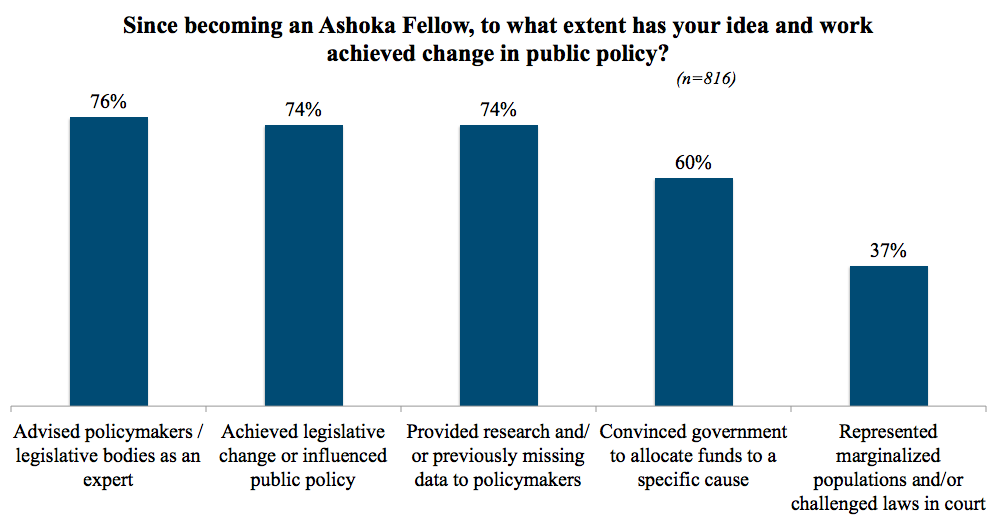

However, in addition to new legislation, Ashoka measured several other “targeted systems change” strategies for policy change in the 2018 Global Fellows Study. Especially for Fellows living in countries prone to political corruption and high attrition rates of government officials, legislative change may not be the most feasible or sustainable solution. Other strategies that Fellows employ to change public policy include representing marginalized populations or challenging laws in court, convincing governments to allocate funding to a specific cause, advising policymakers as an expert, or providing research/previously missing data to policymakers. All of these strategies can be thought of as subsets of the overall category of “policy change.”

Indian Fellow Sailakshmi Balijepalli is involving stakeholders such as local governments, educational institutions, and private providers to address the gaps in public healthcare with a particular focus on neonatal and maternal health. Sailakshmi has been intentionally working to convince the government to allocate funding to her idea (one of the “targeted systems change” strategies for policy change) so that it can be replicated and scaled at a level she could not have achieved on her own. By convincing the government to take up her idea, she is able to scale her community-based healthcare model across the country without increasing her staff, operating budget, or number of direct beneficiaries.

“What we have achieved by collaborating with the government of Tamil Nadu and operationalizing 73 Neonatal Intensive Care units across the State to bring down Infant Mortality Rates, that model is being replicated in other states of India. And apart from this, global chapters are being set up where members learn the model hands on and manage it through local chapter implementation.”

Market Change

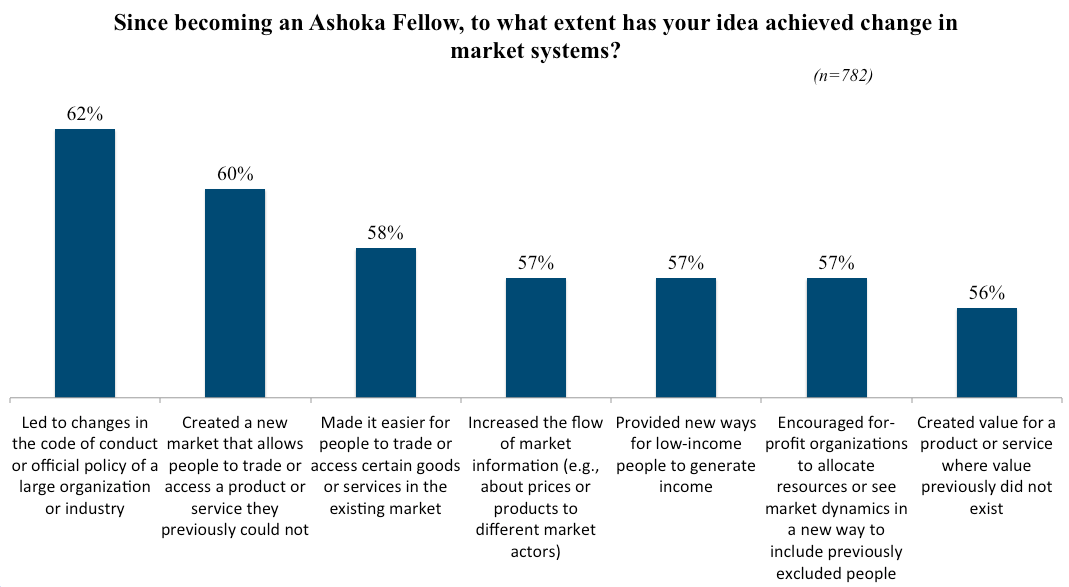

Similar to policy change, developing indicators to measure systems-level change in markets presented a challenge. The indicators needed to be inclusive of Fellows both in developed markets with strong infrastructure and investment, as well as those in markets dealing with volatility and insufficient capital. Under the large umbrella of “market systems change,” we used the indicators below to measure more targeted systems change strategies.

Overall, 93 percent of Fellows report having changed market systems at the international, national, and/or regional levels. The majority of Fellows have achieved change at the national level (70 percent) and the regional/local levels (55 percent). 40 percent have achieved change at the international level.

The most common targeted systems change strategy reported was “creating new markets” with 60 percent of Fellows reporting that they had achieved this type of change. For example, U.S. Fellow Kevin Kirby is creating a new market for substance abusers, their loved ones, and their employers to both prevent and treat addiction. Kevin is breaking down stigma around addiction, in part through a public education campaign, but mainly by pointing out the economic incentives for employers to become part of the solution. To date there is no other for-profit organization that has targeted employers with these types of prevention and treatment services.

“There's nothing even remotely like us in our field. There's nobody penetrating the private sector and delivering value to those with the most skin in the game in the community, being employers. We could have an army of peer addiction management coaches operating out of our facilities. But if we haven't done anything to systemically address the issue in a community, we're just another service provider. [Our services are] a necessary step, but we also have to mainstream addiction into the employer-employee relationship or we're not going to get sufficient penetration to solve the problem in a community. We also have to mainstream addiction into healthcare.”

New Insights Emerging Around Systems Change

1. Significant Gender Differences Exist in Systems Change Achievement

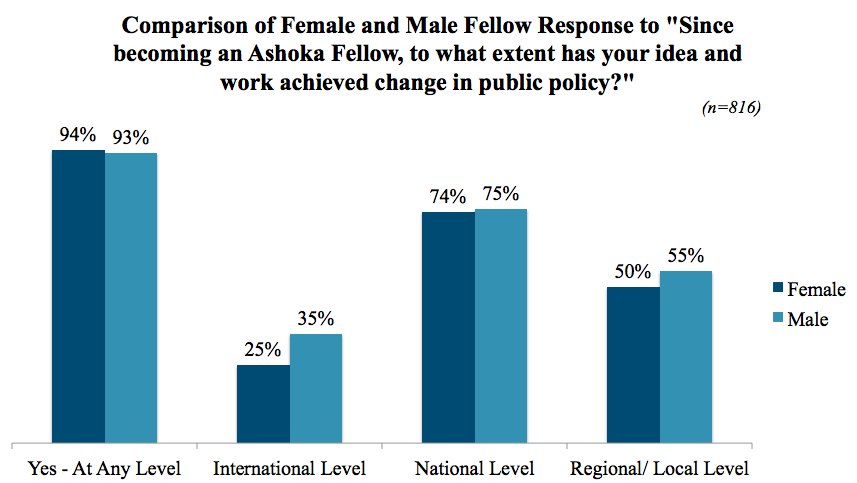

For independent replication, policy and market systems change indicators with international, national, and regional levels of achievement, a consistently higher percentage of male Fellows reported achieving change at the international level. This difference is notable because overall, a higher percentage of female Fellows reported achieving systems change at any level. While female Fellows often achieved higher rates of systems change at the national and/or regional levels, a much higher percentage of male Fellows were achieving systems change at the international level -- sometimes with a difference of more than 25 percentage points.

According to female (and male) Fellows consulted in the qualitative interviews, a complex web of factors influenced these differences, including a general lack of female representation in leadership positions, and in certain sectors discrimination and stereotyping and barriers to fundraising and investment for female Fellows. In the qualitative interviews we also discovered that male Fellows tend to collaborate more exclusively with other male Fellows, while female Fellows tended to collaborate more equally with all genders. For a more in-depth discussion of gender differences emerging from the study results, please see Iman Bibar’s article in this issue.

2. Systems Change Rates Have Been Increasing Over Time

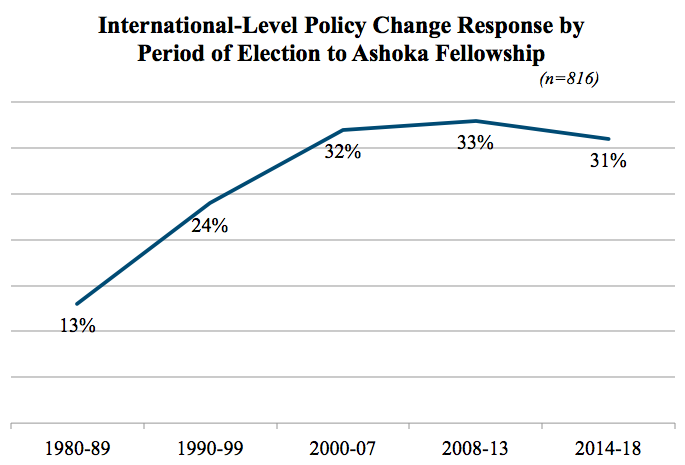

When we look at the data by election period, a new trend emerges: rates of international-level systems change have been increasing over time for policy change, markets change, and replication. This increase is particularly pronounced because Fellows elected more recently, by definition, have had less time than their peers to create systems change.

The shorter timespan makes this find all the more striking: Fellows elected in the past five years are already reporting the same levels of international-level systems change as Fellows elected in the 1980s and 1990s. For most measures of social impact we would expect that Fellows elected more recently would have lower rates of systems change, simply because it takes time to achieve.

Why are Fellows elected since 2000 (particularly those elected since 2008) making systems change faster than their peers elected in the 1980s and 1990s? This finding certainly may reflect a bias in Ashoka’s selection process in recent years towards Fellows who are on track to create international-level systems change. However, most Fellows are selected at an early stage of their idea and it would be nearly impossible to predict international-level systems change. More research is needed to understand this phenomenon, but one hypothesis is that globalization and new digital tools like Facebook and Skype may be assisting Fellows in increasing their rate of international change. Other hypotheses include network effects from other Fellows and from the social entrepreneurship sector more broadly as it has continued to evolve from the 1980s.

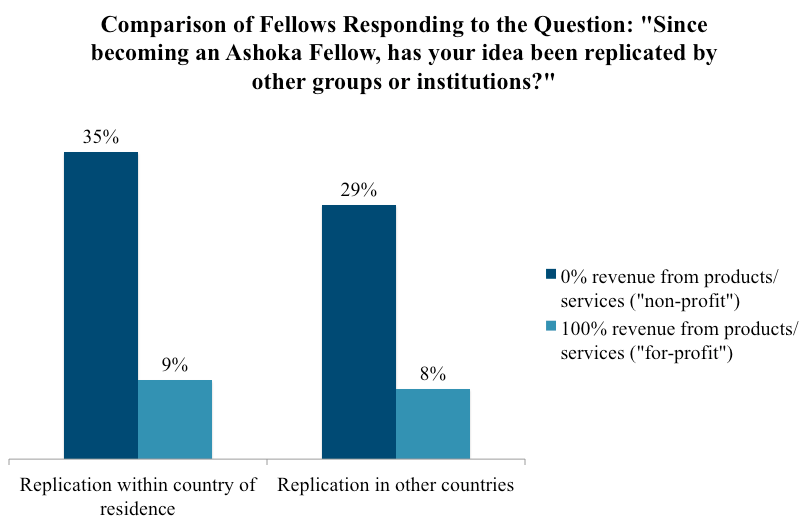

3. Fellows Whose Organizations are Pure “Nonprofits” Have Higher Rates of Systems Change

In the survey we asked Fellows “What percentage of your organization’s revenue comes from selling products/services?” This question was intended to be a proxy for the type of organization Fellows run -- whether for-profit, nonprofit, or hybrid. Overall, just under one-third of Fellows responded “0 percent” to this question, indicating that they are non-profits. 12 percent of Fellows reported that 100 percent of their revenue comes from selling products/services, indicating that they are either for-profits or have a hybrid model.

On every systems change question in the study, we found that non-profit Fellows reported much higher rates of change. For example, 32 percent of nonprofit Fellows had achieved change in legislation or public policy compared with just 12 percent of for-profit Fellows. The comparison between these two groups on independent replication was even starker, as seen in the chart below.

Similar to independent replication, a much higher percentage of Fellows who reported no revenue from selling products and services focused on mindset shift as “core to their strategy” -- 33 percent compared to 11 percent of Fellows who reported all of their revenue from selling products and services.

Learnings from a Smaller Group of Fellows Who Have Achieved Systems Change on At Least Three Levels

We decided to take a subset of the data by creating a new group called the “Systems Changers” (SCs) who reported that they had achieved systems change on at least three levels -- independent replication, focus on mindset shift, and public policy or market systems change.i We analyzed this smaller group of 501 “SC” Fellows (58 percent of the respondents) to see if there were any characteristics significantly different from their peers that might explain their systems change achievements.

To eliminate any potential bias, we first compared whether SCs were more or less likely to have received an Ashoka stipend. Ashoka tends to give stipends to Fellows who are at an earlier stage of their idea and are more in need of funding. Therefore, if the percentage of SC and non-SCs who received a stipend is the same, then we can determine that neither group had any “advantage” in terms of being more advanced in their idea when selected for the Ashoka Fellowship. There was a small difference in stipend awarded (79 percent to non-SCs compared to 86 percent for SCs), which means that SCs are slightly more likely to have begun their Fellowship as earlier-stage entrepreneurs.

1. Systems Changers Are More Likely to Collaborate

In the study we found that SCs as a group were more likely to collaborate, both with their peers and others. Within the Ashoka network, 79 percent of SCs have collaborated with another Fellow compared to 66 percent of non-SCs, and 24 percent of SCs have collaborated with six or more Fellows compared to just 10 percent of non-SCs.

We also found that outside the Ashoka network, SC Fellows continue to show higher levels of collaboration with every stakeholder group. For example, 64 percent of SC Fellows report partnering with national government compared with 48 percent of non-SC Fellows, and 61 percent of SC Fellows report partnering with primary/secondary schools compared with 38 percent of non-SC Fellows. This finding could be interpreted as correlational evidence of Fellows’ systems change achievements (Fellows who achieve systems change will have been successful in collaborating with more stakeholder groups), or it might signal that SC Fellows are successful because of their inclination towards collaboration. Additional research is needed to understand how collaboration may factor into Fellows’ systems change achievements.

2. Systems Changers Are More Likely to Change Their Strategy

Overall, SC Fellows are more likely to continue to pursue their original idea than non-SC Fellows (93 percent and 87 percent respectively), which is to be expected. A potentially new insight is that of Fellows who are still pursuing their original idea, a much higher percentage of SC Fellows report having changed their strategy significantly to achieve the same idea. 53 percent of SC Fellows report that they are “working on the same idea, but my strategy has changed significantly” compared to 42 percent of non-SC Fellows.

Similar to previous findings, we do not know whether this insight is correlation or causation -- are Fellows achieving systems change success because they changed their strategy or because they were the type of leader who was open to “failing fast” and evolving from the beginning? Additional research is needed to understand the characteristics of SC Fellows and whether being open to significant strategic changes is a factor in Fellows’ ability to create systems change.

Conclusion

Ashoka’s thinking on measuring systems change has evolved significantly over the past 38 years, but the most important component of systems change -- measuring Fellows’ idea spread -- has withstood the test of time. New technologies, tools, and models for institutional, political, and citizen movement organization will continue to disrupt how we measure Fellows’ systems change strategies.

In the four “big vision” categories measured in this study, the results demonstrate that Ashoka’s strong selection process and criteria elects social entrepreneurs who are achieving significant systems change and seeing their idea replicated by independent groups in changing mindsets, policies, and market systems.

This data is crucial in showing us what kinds of systems change Fellows are having, including by gender, election period, and geographic context. However, it does not explain how Fellows make strategic decisions or why certain groups have different outcomes (such as female Fellows having lower rates of international level change than male Fellows). Now that we have the what, it is much easier for Ashoka and the global community of researchers, academics, policymakers, and nonprofit leaders to dig into the how and the why social change is happening to create a stronger and more effective ecosystem for all social entrepreneurs to create transformative and sustainable change.

Endnotes

i Included in this group were Fellows who reported that mindset shift was “core to their strategy,” Fellows who reported that their idea had been replicated by independent groups either within country or internationally, and Fellows who reported making either policy or market systems change at any level. Some Fellows’ work does not focus on markets, and some Fellows are not able to influence policy due to political and socioeconomic barriers. Therefore for this cohort of “Systems Changers” we included Fellows who, in addition to focusing on mindset shift and having seen their idea replicated, had achieved systems change either in policy or markets.

Works Cited

1 Bloom, Paul N., and Gregory Dees. "Cultivate your ecosystem." Stanford Social Innovation Review 6.1 (2008): 47-53.

2 Osberg, Sally, and Roger Martin. “How Social Entrepreneurs Make Change Happen.” Harvard Business Review (October 2015).

3 Leviner, Noga, Leslie R. Crutchfield, and Diana Wells. "Understanding the impact of social entrepreneurs: Ashoka’s answer to the challenge of measuring effectiveness." Research on Social Entrepreneurship and Contributing to an Emerging Field (2006): 89-103.

4 Waitzer, Jon McPhedran, and Roshan Paul. "Scaling social impact: when everybody contributes, everybody wins." Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 6.2 (2011): 143-155.

5 Mühlenbein, Odin. “Systems Change — Big or Small?” Stanford Social Innovation Review (February 2018).

6 For a more in-depth explanation of different independent replication techniques adopted by Fellows, please see Ashoka Belgium’s presentation on the topic: www.socialeinnovatiefabriek.be/sites/default/files/