Student nurses demonstrating water purification in a rural community

Problem and Context

Cameroon is located in Sub-Saharan Africa, geographically lying between West and Central Africa. The country has a population of 25 million people (CIA 2019). Health professions education in the country is supervised by three government ministries -- Higher Education (diploma and degree programs); Public Health (diploma programs); and Employment and Vocational Training (diploma programs). Schools that train health professionals in the private sector will have to be accredited by one of these ministries depending on the programs they intend to run. Some of the programs are harmonized (similar curriculum is used across schools) while some others are unique to the institutions running them. Where programs are harmonized, you will see similar activities, including internships taking place in the different institutions.

In the course of their programs in different institutions, students will undertake both clinical and community internships as is the standard. Clinical internships take place in hospitals while community internships take place in communities where primary health services are located. For the community internship to be successful, the school, the primary care health center, and the community leaders must collaborate. In the communities, the students will typically conduct health educations and community health needs diagnoses. These diagnoses usually paint a picture of community needs that are affecting the health of the people. The students will present this in their post-internship reports to receive a grade. The data thus generated was not used as the emphasis was on the internship as an academic activity to be completed by the students. Even though the reports usually included complaints from the communities who expected more than just assessments and health education, the institution didn’t think it could do more for them. The communities wanted intervention projects, but the institution did not have the financial resources that such interventions would warrant. We had to reflect on strategies to make the community-institution partnership more beneficial to the community members in a sustainable and cost-effective manner.

Innovative Solution

A team from two institutions (Health Research Foundation Buea and Biaka University Institute of Buea) worked to develop a social accountability-based model. Social accountability was first defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1995 as “the obligation of medical schools to direct their education, research, and service activities towards addressing the priority health needs of the community, region, and/or nation they have a mandate to serve. The priority health needs are to be identified jointly by governments, healthcare organizations, health professionals, and the public.” Both institutions have always tried to be socially responsible, i.e. describing social needs implicitly, internally setting their objectives, developing community-orientated programs, and internally assessing their successes (Boelin et al. 2016, 1078-1091). They equally ensured that their programs were socially responsive, i.e. explicitly describing community needs inspired by data from the community, being community-based, and measuring success through actually achieved outcomes (Boelin et al. 2016, 1078-1091). What was lacking was that the concept of social accountability had not been directly incorporated into their philosophy and operations. In this regard, they were more reactive than anticipatory in their projects, defined their success internally, and didn’t strongly consider unique solutions for each context. This critical awareness was essential in developing a model that built on community needs. It had to incorporate community stakeholders in addressing these needs using locally available resources, while at the same time identifying strategies to meet future needs.

The development of the model was influenced by the awareness of three key realities from past experiences: (1) there will be little or no external funding to initiate and sustain any identified projects; (2) rural communities have always demonstrated the ability to address some local problems by themselves; and (3) the presence of student nurses in the communities had always increased the number of service users visiting the health centers. The underlying assumption of the model was that students can be prepared to help communities to implement sustainable initiatives to address health and health-related needs. A special 12-hour orientation curriculum was developed to reinforce key aspects of community dynamics, leadership, and community participation. The goal was to strengthen their competence in managing relationships with communities. Communication, leadership, problem-solving, and team and cultural sensitivity skills were emphasized in this training. The training was designed as a workshop and delivered over three to four sessions during the week prior to their community postings. Students were then randomly assigned to the different rural communities with the students in the same community constituting one group. Each group was allocated a staff advisor whose role was to provide guidance and advise. The groups have their initial meetings on campus before moving to their respective communities where they spend 12 weeks. In the communities, the students are based in the health center where they are involved in all the clinical and outreach activities of the health center. Being final year undergraduate nursing students, they are expected to be able to conduct most of the clinical activities within their scope of practice with minimal supervision from the health center nurses. In the community, the students are expected to meet the traditional leaders, introduce themselves and their objectives in that community. This should help them secure authorization and support to visit homes, groups, and communal facilities and to work with community members.

While there exists an established relationship between the school, the health centers, and the community leaders, each group of students has the responsibility to secure support and goodwill from community leaders and members. When they obtain the blessings of the community authorities, they start conducting visits to homes and other facilities (schools, markets, water catchments, etc.) within the community. In the course of these, they establish a diagnosis of the health and health-related needs and then coordinate with community members to develop and implement appropriate solutions to a selected problem. The solution must be realistic and require only resources that can be mobilized within the community.

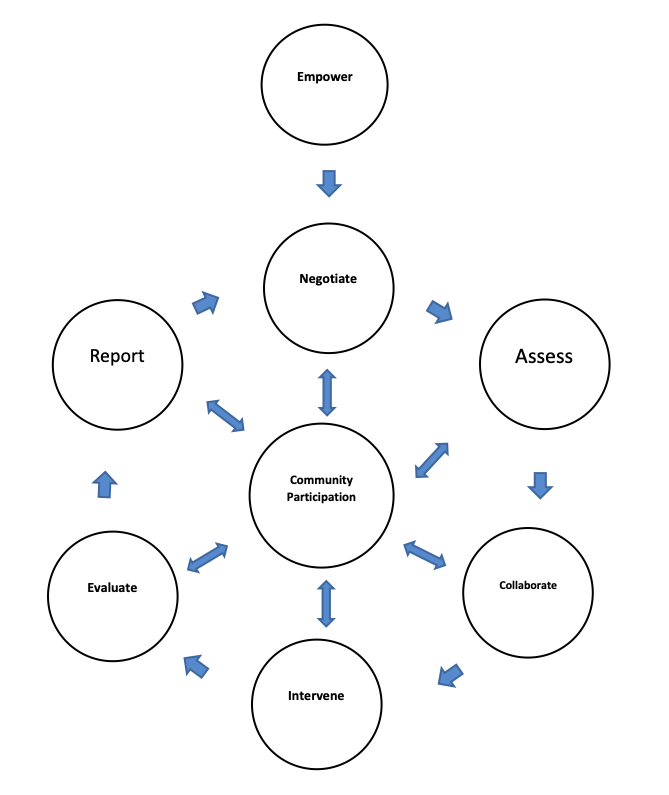

In summary, this student-led model has the following components: empower, negotiate, assess, collaborate, intervene, evaluate, and report (ENACIER).

Student nurses (in white t-shirts) conducting health screenings in a rural community.

Unique Characteristics of the Model

Many articles on social accountability have focused on medical schools (Boelen, Dharamsi, and Gibbs 2012, 180-194; Pourabbas et al. 2015, 77-80; Boelena et al. 2016, 1078–1091; Abdolmaleki et al. 2017, 55-70). The ENACIER model was tried with nursing students and shows distinct characteristics from other social accountability models used in the health professions. The Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet) advocates for a socially accountable transformative workforce (International Federation of Medical Students Association -- IFMSA and THEnet 2017, 2). Their model provides a value-based process to guide medical institutions to evaluate the level to which they are meeting the needs of the communities they serve (IFMSA and THEnet 2017, 2). This is an in-ward looking system for the members of the institution to assess the institution’s own level of social accountability. The Global Equity Gauge Association (GEGA) in 2003, proposed a framework that was based on social justice and sought to emphasize advocacy, community empowerment, and assessment of health inequities. Another model is the CARE (Clinical activity, Advocacy, Research, Education and training) model. This is a tool for identifying priority health concerns of underserved communities so that the institution can implement cultural and curricular change to help address them (Meili, Ganem-Cucena, Leung and Zaleschuk 2011, 1114–1119). All of these models revolve around improving health access for disadvantaged groups. A model of social accountability that slightly deviates from these examples is the AIDER model. AIDER (assess, inquire, deliver, educate, and response) is a “continuous monitoring process that explicitly incorporates reciprocal education and continuous collaboration with underserved stakeholders, integrating community participation at all levels (Sandhu, Garcha, Sleeth, Yates, and Walker 2013, 1404-1405). The model is cyclical and continuous and though it integrates community participation, it is driven by the physician. Greer et al. (2018, 60-65) describe another community focused model -- NeighbourhoodHELP, in which students in their medical program are assigned a household in medically underserved neighborhoods. For three years they partner with students from other schools to provide home care services to their selected household.

Community participation is the common factor in the ENACIER and AIDER models. When the community is involved in all aspects of these processes, they become empowered to take on these issues on their own. However, the ENACIER model is unique in that it is student nurse driven and designed to play two major roles: developing specific competencies in the learners and bringing palpable interventions in communities.

The Empower Model focuses on developing the student nurse’s ability to access the community as professionals with the goal of helping the community develop homegrown solutions to jointly identified health and health-related problems. This is achieved through the intensive 12-hour preparatory curriculum and the input of the staff advisor. This academic staff-led process takes place in school and does not include community members. This explains why it is not included in the cycle of activities that occur in the community.

Negotiate deals with the process of the students navigating power structures and community groups to build trust and secure support. They meet the traditional authorities, group leaders, and other influential members of the community whose help is needed to facilitate their work and stay in the community. A failure of this aspect will result in limited access into the community. This might mean student nurses will not be able to work beyond the confines of the health center.

Assess involves the students identifying first the community structures and persons they need to work with. Once negotiations are done, not every stakeholder will be needed for the next phase of activities. For example, after meeting the traditional ruler of the community and securing his support, the students have to identify the quarter heads that they will need to coordinate with on a daily basis. This will depend on many factors including which part of the community they will want to focus on. Some communities are so large or have inaccessible areas that influence where the students can work. Next, the students with the collaboration of those identified, use appropriate diagnostic tools to identify health and health-related needs of the community.

Collaborate emphasizes building a coalition of community members, institutions, and the health center staff in the process of developing solutions to the selected problem.

Intervention refers to the joint implementation of the agreed solution to the identified problem. The students and community choose an intervention that is completely within their capacity to implement. They set their objectives and indicators that will help them gauge the level of success. The students are instrumental in helping the community to identify these resources within themselves and how to use them to solve their health and health-related problems.

Evaluate has to do with the project participants evaluating the level of success in the implementation. This is guided by the objectives they set out at the beginning of the intervention.

Report is where students use a format provided by the school to prepare an academic report on the entire process and its outcomes. Copies of this report are shared with the health center which shares it with other community leaders and structures. The report findings from the previous year usually contribute to the negotiation process for new student groups.

Figure 1: An illustration of the ENACIER model.

Figure 2: The ENACIER Model

The ENACIER model considers a three-way partnership between the school, community, and health center. The health center drives primary care in the community but is usually underutilized in the local communities. Utilization significantly goes up during the 12 weeks that students are deployed in the community health centers. Using the student nurses to strengthen the bond between the health center and its community ensures that projects developed as such can continue even during the months when students are not in the community. The model does not require deployment of significant resources as the parties learn to use only what is at their disposal therefore fostering a spirit of self-reliance as well as a new approach to dealing with community challenges. Another significant difference between our model and other models is that it is not disease focused. Any factor that has a direct or indirect effect on health could be addressed if the participants so desire. This allows us to achieve social accountability, empower communities, build networks, turn students into change leaders, and demonstrate that public-private partnerships are possible even in the most peripheral rural settings.

Outcome and Impact

From the 2010/2011 academic year when this model was first rolled out, right up to the 2016/2017 academic year, a total of 585 final year undergraduate student nurses have taken part in the program as shown on Table 1

Table 1: Student Participation Rates in the ENACIER Model

| SN | Academic Year | Number of Students |

| 1 | 2011/2012 | 88 |

| 2 | 2012/2013 | 78 |

| 3 | 2013/2014 | 126 |

| 4 | 2014/2015 | 82 |

| 5 | 2015/2016 | 100 |

| 6 | 2016/2017 | 111 |

During this time, student-community led interventions successfully took place across 10 communities:

Type 2 diabetes management (two communities): student nurses used point-of-care testing to screen and diagnose people with diabetes mellitus. They went on develop nursing management plans which were implemented both at the level of the patient’s homes and the health centers. This activity was not part of the routine activities of the health centers in these communities. Treatment and care also included health education on diabetes.

Water sanitation (six communities): the projects here included laying down pipes to bring water from catchment sources into the community so that communal taps could be available; support construction of a water catchment; and enable the development of a plan for routinely cleaning the central water source.

Teenage pregnancy control (one): in one community with high prevalence of teenage pregnancies and school dropouts, the student nurses worked with young people to increase awareness of reproductive health. The result was a 70 percent increase in the number of teenagers who came to the health center for birth control services in the first year of intervention alone.

Refuse management (one): in this community the student nurses and the community worked to establish a system of separating refuse. Biodegradable refuse was deposited in the farms to serve as organic manure while plastics and other nondegradable materials were taken to dumps managed by the local council.

All communities reported greater satisfaction with the model. The students too reported increased readiness to work in rural communities and the feeling of fulfilment from helping the communities to realize these projects. Student reports showed significant evidence of leadership competences. Two projects (diabetes management and aged curriculum development) built from this model template have been published as health professions education innovations in the Medical Education Journal.

The rural diabetes management project used a 12-hour curriculum to prepare student nurses to use point-of-care testing to screen, diagnose, and manage diabetes mellitus in two rural communities (Leke, Portwood, and Maboh, 2013, 1122). During the 12-week internship, the students applied the ENACIER model with significant results. They worked with the health center nurses to screen for, and manage, the care of diagnosed diabetics and high-risk cases. In the first year of implementation, a total of 334 clients were screened; overall diabetes prevalence was 4.89 percent; 11.31 percent were at high risk; and 35.78 percent were at risk (Leke, Portwood, and Maboh 2014, 37-44). The project’s successful implementation in two rural communities benefited the patients, community members, health center staff, and students. This project still operating on the ENACIER model received a three-year World Diabetes Foundation grant in 2017, to expand the project to six rural communities.

The ENACIER model was also adapted in the development of the first community-based curriculum for geriatric nurse training in Cameroon. Using findings from previous student-led community projects, a one-year post-registration curriculum was designed to train nurses in geriatric care. At the core of the design is the care of older adults within their own homes and communities (Maboh, Leke, and Nyenti 2013, 1121). This curriculum was culturally sustainable because it built on the traditional values and perceptions of aging. Family caregivers and older adults, through interactions with the student nurses learn more about aging and how to provide care and support for the elderly members of the family. Community-based elderly groups are key partners in the program as they provide more extensive access to older adults living in their communities. More than 100 graduates have successfully completed this program between 2011 and 2017. While many of the graduates have gone on to find jobs and further education opportunities, two of them started their own independent community-based elderly care services.

We have seen stronger cooperation ties between the school and communities. The reception of students and the cooperation they receive in the community keeps growing. The project team has received recommendations from beneficiary communities to get other schools that send students for internships to adopt this model. The health center staff and regional health officials of the Ministry of Public Health have also increased their support and cooperation with our school. Most importantly we have graduates from this program working in all the health districts that have been used for this project this far.

Expected Social Impact

In introducing this model, it was expected that community internships could be transformed from a purely academic exercise where students pick up clinical skills in primary care centers, to a veritable tool in change leadership. The modification of the community internship was a response to local communities’ desire to not only be “used” for student learning but also to see real benefits from that interaction. At the institutional level, we expected to build consensus among academic staff and administrative staff to support a complete overhaul of this component of the curriculum for the final year nursing students. Staff called to play the role of advisors were expected to take a back seat and allow the students to lead their project as it best fit the context of the communities they were assigned to. This primarily advisory role also included potential for the advisor to work with the student groups to develop their reports into publications if they so desired. We also inspected the two institutions involved in the development of the model to adapt and expand the concept of social accountability actively across all other aspects of their services and operations.

At the local level, we expected to see increased satisfaction from the community and health center staff with our new approach. We also expected the health center staff while supervising the student nurses to also learn some new techniques and protocols from the students thus strengthening their connection. The improvement of quality care in the primary health centers was another expectation. Considering that final year student nurses have already acquired significant clinical skills, they were able to expand services in the health center. They could take on many simple routine activities that didn’t need direct supervision, thus giving the usually few nurses more time to improve on the quality of services. In some communities, due to low staffing levels, it is only when students come to the health center that home visits and other outreach services become a weekly routine once more. This strongly contributed to the increased utilization of the health center services during the internship periods. We also expected to see new community-based models being generated to address different aspects of community needs. The project team expected that other institutions will adapt the model to their own programs thereby making social accountability a permanent part of their operations. We also expected that through this model, there will be a general improvement in the overall health of the community.

Internationally, many poor countries with primary care challenges could find this model as a simple, sustainable tool to use social accountability to achieve positive outcomes in health professions education, community health, and health systems improvement. Advanced countries with more developed health care systems can find aspects that could be incorporated into their systems as they try to move health care back into homes and communities.

Generally, we expected that stakeholders would realize that self-reliance and community cooperation could help communities solve quite a significant number of problems even without government or external support.

Funding of Model

The model did not require extra allocations as it was built into existing structures that were already being funded. The community internship already existed as part of the curriculum. It just needed to be modified to achieve the project goals. Deployment of students to communities including supervision visits by staff advisors were already part of the nursing department’s budget thus requiring little extra funds. In the communities, the stakeholders decided how they will secure the resources needed for the agreed intervention within their community. Student nurses needed only their routine clinical tools required during placements. They did not need any extra tools for this activity. Depending on the nature of the intervention, they could use existing resources in the health centers or work with community members to mobilize resources. For example, in one of the communities where a pipe-borne water project was selected, the students supported the community fundraising through health education on risks and benefits of pipe-borne water. So, community members saw reason to make small financial contributions towards the project. Financial resources are usually the most difficult to come by in these systems and as such, designing the model in such a way that no significant financial resources are needed increased the chances of success.

Scaling and Policy Implications

In centralized government systems like Cameroon, private sector and local communities have very little influence on policy development and implementation. Everything is centrally decided, funded, and implemented. However, the project team kept close contact with regional health authorities as different aspects of this project were implemented in the communities. Reports and data from the field are routinely shared with these regional authorities even as we seek to maintain their cooperation in facilitating access to the regional health structures. It is expected that this data sharing could influence some of their policy decisions. For example, we are expecting to see the diagnosis and management of Type II diabetes become part of the minimum package of activities of the rural health centers since access to specialized treatment centers in urban areas remains a challenge to rural dwellers. One avenue exploited for scaling the model has been other schools that train health professionals in the country.

The project team supported the third author in adapting the model for community health internships in a state-owned nursing school in the region. With support from Health Research Foundation, she was able to prepare students to lead communities with little or no access to pipe-borne water to use locally available resources to treat their drinking water. This project was started in 2015 and is currently in its third year. Another positive sign here is that the students of this second school are working with communities that have not been used for the project before. The students also went further to create a social media page where they shared their experiences in the community.

While this is the first time that the model is being published as designed, projects that were adapted from it have been published. These publications have helped other institutions to develop similar projects. For example, another institution in another part of the country, launched its own geriatric care curriculum four years after the successful implementation of the model developed by the project team. Health Research Foundation has developed a package to support both public and private health professions training institutions to implement the ENACIER model. The rollout of this plan has been stalled by the growing insurgency in that part of the country.

Conclusion

Nursing schools can use student internships to foster collaboration with local communities to assist them to leverage local resources to meet their needs. Students led communities to see for example that they could take charge of their own clean water supply without government assistance.

Transformational learning that moves students from simply identifying and reporting problems to being resource persons and leaders, improves community health outcomes. The diabetes project for example demonstrated that, students using point-of-care testing, could mobilize individuals and groups, conduct screening, implement individualized care, facilitate referrals, and provide genuine health data. This earned an external three-year funding grant in 2018 to expand the project to six more communities.

Curriculum designs drawn from local needs can lead to unique but transferrable models of providing culturally and economically sustainable care to individuals and communities. The geriatric program showed that professional aged care could fit into a culture that promotes aging at home.

Curriculum designs help learners develop a wide range of skills: communication, networking, consensus-building, critical thinking, cultural responsiveness, problem solving, and leadership. This is achieved during the process of negotiating and interacting with community leaders, groups, and individuals. It also makes working in rural settings appealing.

Nursing schools can be the nexus of intersectoral collaboration for health if they adopt social accountability models similar to the ENACIER model.

Works Cited

Adolmaleki Mohammadreza, Yazdani Shahram, Momeni Sedigheh, and Mmtazmanesh Nader. 2017. “A Social Accountable Model for Medical Education System in Iran: A Grounded-Theory.” Journal of Medical Education 16, no. 2 (Spring): 55-70

Boelen Charles, Dharamsi Shafik and Gibbs Trevor. 2012. “The Social Accountability of Medical Schools and its Indicators.” Education for Health 25, no. 3 (December): 180-194

Boelena Charles, Pearson David, Kaufman Arthur, Rourke James, Woolard Robert, Marsh C. David and Gibbs Trevor. 2016. “Producing A Socially Accountable Medical School: AMEE Guide No. 109.” Medical Teacher 38, no. 11: 1078-1091. dx.doi.org/10.1080/

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). 2019. “The World Factbook: Cameroon” Accessed June 14, 2019. www.cia.gov/library/publications/

Greer J. Pedro Jr, Brown R. David, Brewster G. Luther, Lage G. Onelia, Esposito F. Karin, Whisenant B. Ebony, Anderson W. Frederick, Castellanos K. Natalie, Stefano A. Troy and Rock A. John. 2018. “Socially Accountable Medical Education: An Innovative Approach at Florida International University Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine.” Academic Medicine 93, no. 1 (January): 60-65

International Federation of Medical Students Association (IFMSA) and Training for Health Equity Network (THEnet). 2017. “Student’s Toolkit: Social Accountability in Medical Schools.” Accessed June 18, 2019. https://ifmsa.org/social-accountability/

Leke Z. Aminkeng, Portwood Cheryl and Maboh N. Michel. 2013. “Diabetes Management: Student Nurses Contribute Using Point-of-Care Testing” Medical Education Journal, 47(11): 1122.

Leke Z. Aminkeng, Portwood Cheryl and Maboh N. Michel. 2014. “Breaking Barriers to Diabetes Management in Rural Communities: Student Nurses Make a Difference Using Point-of-Care Testing.” GSTF Journal of Nursing and Health Care (JNHC) 1, no.2 (August): 37-44. DOI: 10.5176/2345-718X_1.2.33

Maboh N. Michel, Leke Z. Aminkeng and Nyenti B. Pauline. 2013. “Curriculum for Community-Based Nurses on Care of Older Adults.” Medical Education Journal, 47(11): 1121. doi: 10.1111/medu.12350

Meili Ryan, Ganem-Cucena Alejandra, Leung J. Wing-sea, Zaleschuk D. 2011. “The CARE Model of Social Accountability: Promoting Cultural Change.” Academic Medicine 86, no. 9 (September): 1114-1119

Pourabbas Ahmad, Amini Abolghasem, Fallah Farnoush, and Alizadeh Mahasti. 2015. “Management of Social Accountability in Medical Education at Tabriz University of Medical Sciences.” Res Dev Med Educ 4(1): 77-80. doi:10.15171/rdme.2015.012

World Health Organization (WHO). 1995. “Defining and measuring the social accountability of medical schools.” Geneva: World Health Organization.

Author bios

Dr. Maboh M. Nkwati is the pioneer Head of Nursing and Deputy Vice-Chancellor for Academic Affairs at the Biaka University Institute of Buea Cameroon. He has been working for 14 years in health professions education and academic governance. He is passionate about improving individual and community health through education and has been active in the development of health professions education in Cameroon. In this context he has led curriculum development in a wide range of health and nursing subject areas. His primary research interest is in the area of health professions education (and improving health care through education), active learning, and elderly care. This has led to publications in academic journals that include articles on innovative approaches to curriculum development, elderly care, student-led community health improvement projects, and the evolution of professional education. He is also introducing the concept of interdisciplinary clinical simulation in health professions education in Cameroon at Biaka University Institute of Buea.

Maboh is also serving as member of the academic board of Equals Institute Australia. He is co-investigator of a World Diabetes Federation funded project to improve rural diabetes management using a synergy of student nurses and primary care nurses in the South West Region of Cameroon. He is a member of multiple professional associations in Cameroon and internationally. He is actively involved in professional advocacy and the fight against fraud in health professions education and practice. He is also the founder of the Health Research Foundation that provides health research consultancy and training services in Cameroon

Maboh’s educational background includes a Bachelor of Nursing Science and Master’s in Nursing Education from the University of Buea Cameroon, and a PhD from the University of Essex in the United Kingdom. He is also a 2012 Fellow of the Foundation for the Advancement of International Medical Education and Research (Philadelphia USA).

Dr. Aminkeng Z. Leke is fellow (2011) of the Foundation for International Medical Education and Research (FAIMER)-USA. He holds a BSc. in medical laboratory science and MSc in chemical pathology from the University of Buea-Cameroon; and a PhD in Pharmacoepidemiology from Ulster University-UK.

Since 2007, he has served in various administrative and academic roles at Biaka University Institute of Buea; his latest (in 2016) being Deputy Vice Chancellor for Research, Cooperation, and Quality Management.

Dr. Leke has been a lead member of many curriculum development committees on health professions education in Cameroon. His manual “Medical Laboratory Science for Nurses” written in 2008 has been a great educational resource for many nursing students across Cameroon. He has a keen interest in community health and maternal/infant health. He led an innovative project on diabetes management in rural Cameroon that won the TUFH Projects that Work International Award in 2015. This project is currently being funded by the World Diabetes Foundation with potential nation-wide adoption. One of Dr. Leke’s recent projects has produced the first data on maternal medication use and safety in pregnancy in Cameroon. In his past work in Europe, he investigated maternal use of antibiotics and risk of congenital anomalies by analyzing the European Surveillance of Congenital Anomaly (EUROCAT) database. Currently, he is working with the ZikaPlan Global Birth Defects Team to develop an app for the identification and accurate description and coding of congenital anomalies in low-resource settings. He is also involved in the WHO Pregnancy Registry project in Africa.

Pauline B Nyenti is a nurse educator working with the Training Schools for Health Personnel, Limbe Cameroon. She is adjunct faculty in the departments of Nursing at the Biaka University Institute of Buea and the University of Buea, both in Cameroon. Nyenti holds a Master’s in Nursing Education and a Bachelor of Nursing Science from the University of Buea Cameroon. She is also a 2014 fellow of the Foundation for Advancement of International Medical Education and Research (FAIMER) Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She enjoys teamwork and is very passionate about enabling students to discover and develop their capacity to contribute to the health of communities. This has led her to remain active in various community projects involving students both at the Health Research Foundations (HRF) Buea and in schools where she teaches.