Summary

To control costs, healthcare providers and insurers need to focus on achieving population health outcomes rather than simply treating the symptoms of individual patients. Improving population health requires investment in a coordinated, multi-disciplinary approach involving healthcare professionals, social service providers, and legal service providers. The Medical-Legal-Community Partnership (MLCP) integrates legal professionals into healthcare teams to detect, address and prevent the health-harming legal needs of patients. The MLCP improves health outcomes by helping patients obtain health insurance and income supports while decreasing their stress and increasing their confidence and ability to take control.

The Medical-Legal-Community Partnership (MLCP) integrates legal professionals into healthcare teams to detect, address and prevent the health-harming legal needs of patients. Volunteer lawyers and law students collaborate on-site with medical and social service staff to address legal needs like Medicaid eligibility, protection from abuse, utility shut-offs, and food stamp denials. The MLCP is a partnership between Philadelphia Legal Assistance (PLA) and the Philadelphia Department of Public Health (PDPH) to provide legal services to PDPH Health Center patients. We have operated at Health Center 3 since 2013 and Health Center 4 since 2015.

Why Put Lawyers into Health Centers?

To control costs, healthcare providers and insurers need to focus on achieving population health outcomes rather than simply treating the symptoms of individual patients. Recent research estimates that 60 percent of an individual’s health is determined by environmental and social determinants, while only 40 percent of health is influenced by medical care and genetics.1

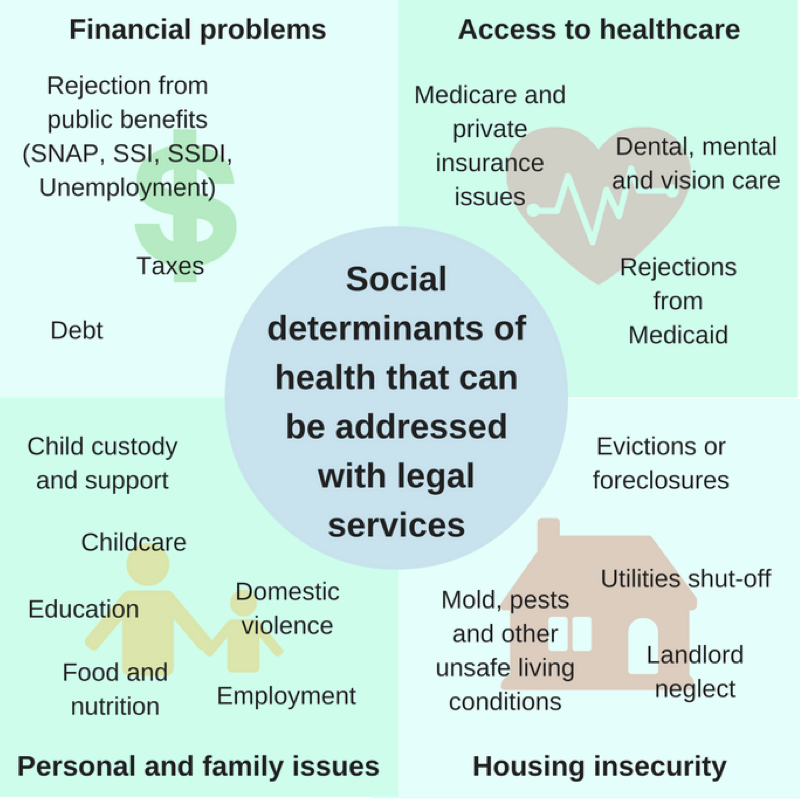

Many of the social determinants of health are legal problems: apartments with code violations, domestic violence, and lack of adequate income for food. The American Bar Association reports that every low-income individual in the United States currently faces 2-3 health-harming legal needs. However, only 20 percent of low-income people with such legal problems obtain the assistance they need.2

This suggests that improving population health requires investment in a coordinated, multi-disciplinary approach involving healthcare professionals, social service providers, and legal service providers.

Integration of Legal Care

By connecting the patients of Health Centers 3 and 4 with legal services, the MLCP seeks to ameliorate health-harming legal needs and empower clients to live healthier, less stressful lives.

When healthcare providers at Health Centers 3 and 4 identify a patient’s legal need, they refer them to the MLCP legal advocate on site. The legal advocate meets with the new client to determine the appropriate course for addressing the issue, which involves offering legal advice, opening a case, or referring the client to an external civil legal aid organization that offers specialized legal services, such as in divorce or immigration cases. Once a case is opened, a team of MLCP legal advocates work together to pursue the legal issue and keep in frequent contact with both the client and the healthcare provider who made the referral. Teams consist of pro bono lawyers and law students, who collaborate on casework to ensure that the highest quality of legal services is provided to clients. When the legal advocates finish their legal work, they report back to the referring provider about the outcome of the referral.

This is a departure from the traditional ways that healthcare and legal services have been delivered. Instead of providing legal services from a downtown office, lawyers are embedded into health centers located in communities where low-income people live. Traditionally, healthcare experts and legal services experts have worked in separate silos. The MLCP brings these areas of expertise together. Legal advocates teach healthcare providers about the law so that they can better spot legal issues.

Over one-third of cases handled by the MLCP in 2015 were related to access to health insurance. MLCP advocates helped clients apply for Medicaid and Medicare, enroll in the Affordable Care Act’s insurance exchange, and challenge improper insurance rejections. When appropriate, advocates also helped clients to access public benefits such as Social Security, disability, food stamps (SNAP), and utilities assistance (LIHEAP) in order to increase low incomes and reduce the health impacts of poverty. The remaining 30 percent of cases were related to employment, wills and estates, housing, and family stability. The majority of patient referrals came from physicians and benefits counselors, who help patients apply for insurance and thus are well-positioned to identify complex cases and improper denials.

The MLCP measures the effect of its work on patients, healthcare partners, and its own volunteers. In 2015, legal advocacy by the MLCP helped clients obtain $320,176 in ongoing annual benefits, such as healthcare coverage and public benefits, as well as $206,242 in one-time benefits, such as the elimination of medical debt. Of patients surveyed, 88 percent said that they felt less stressed as a result of the legal care they received from the MLCP. Three-quarters of healthcare staff surveyed agreed (and 30 percent strongly agreed) that as a result of the legal services they received, patients appeared to be “better able to cope with or manage challenges in their life” (the remaining 25 percent said they did not know). One hundred percent of law student volunteers surveyed said that they would recommend the MLCP as a volunteer opportunity to their fellow law students.

The Business Case for Medical-Legal Partnership

Currently, the MLCP is funded by a combination of government and foundation grants, which support one full-time attorney. The MLCP leverages resources of volunteer lawyers, law student volunteers, and fellowships in order to maximize the quantity of legal services provided per dollar of funding. On average, we spend $700 per case. We achieve $1,050 in average one-time financial benefits per case, as well as an average of $1,460 in annual on-going benefits.

We think our model is cost-effective and scalable. In five years, we would like to have a presence at all eight health centers operated by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health. In order to expand, however, we will need to find a stable source of funding.

Our strategy for growth and long-term sustainability is to demonstrate to government, healthcare providers, and insurers that the MLCP provides a social and financial return on investment. For example, if we successfully appeal a Medicaid denial, the healthcare provider will be paid for services that it might otherwise have to write off. Hospitals benefit because patients have options for care that are less expensive than going to the emergency room. If we assist a “super-utilizer” of health insurance with ameliorating the social determinants that keep them coming back to the hospital, then we can help the insurance company reduce costs.

If healthcare stakeholders can realize the alignment between the MLCP’s mission and their goals, they may provide funding to grow and sustain the MLCP. The MLCP now has a three-year track record and has assisted over 400 patients. We have started conversations with a variety of stakeholders in the healthcare industry about sharing data in order to measure the cost-savings and long-term health outcomes attributable to the MLCP’s work.

There are challenges to funding legal interventions in this way. We have noticed that when our cases result in healthcare cost-savings, these benefits are usually are distributed across many institutions. Until the industry is more coordinated, individual stakeholders may be reluctant to bear the cost of services like the MLCP when the benefits of the service may accrue to non-contributing competitors.

In this environment, the most logical funders are central payers who can fund medical-legal partnerships on a regional or national level and realize the aggregate cost-savings. There are signs that the federal government is moving in this direction. For example, the Health Resources and Services Administration recently clarified that a portion of the Health Center Expanded Services Supplemental Funding could be used to fund medical legal partnerships.

Conclusion

The MLCP improves health outcomes by helping patients obtain health insurance and income supports while decreasing their stress and increasing their confidence and ability to take control. It is one of many interventions that, when widely adopted, will help the healthcare industry achieve lasting health outcomes and ultimately reduce the cost of care.

References

1. Steven A. Schroeder, “We Can Do Better—Improving the Health of the American People,” New England Journal of Medicine 357 (2007): 1221-28, doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa073350.

2. Helaine M. Barnett, “Documenting the Justice Gap in America: The Current Unmet Civil Legal Needs of Low-Income Americans,” Legal Services Corporation (2009), Accessed October 16, 2016, http://www.lsc.gov/sites/default/files/LSC/pdfs/documenting_the_justice_gap_in_america_2009.pdf.