Afterschool staff and school day teachers often face similar challenges when managing youth behavior. Although staff encourage all youth to engage in activities and cooperate with one another, children are never perfect at regulating their behavior. If full-time teachers still sometimes struggle with classroom management, the challenge may be even greater for afterschool staff to manage youth whom they see only three hours a day.

Classroom management is not merely a way to keep students quiet and compliant without disruption. This unrealistic view only causes stress on a facilitator and rebellion from the youth, especially for afterschool programs that distinguish themselves from school day classrooms by providing more freedom and flexibility. In essence, classroom management is a multi-faceted method used before, during and after activities to create an orderly environment that engages academic learning and enhances social and moral growth (American Psychological Association, n.d). The orderly environment is established after youth have been taught expectations of behavior and are consistently held accountable for positive and negative behavior.

Throughout the city of Philadelphia, providers within the Out-of-School Time (OST) Network funded by the Department of Human Services (DHS) are taking on a framework of four key strategies geared toward effective classroom management in OST programs. Under this framework, staff build rapport with youth, establish classroom culture, implement effective discipline policies, and thoroughly prepare each day through advance activities planning.

It is important to note that not all techniques work for every teacher or facilitator, but by recognizing classroom management as an ongoing process, every program has the capacity to engage youth in learning and cooperation. The challenges and methods of classroom management may vary for each program, but the positive outcomes - relationships with youth and adults, as well as learned life skills – are the same.

Building Rapport: Get to know the youth

Building Rapport: Get to know the youth

Because afterschool providers work with youth, it is necessary for staff to learn about the youth they are serving. Building rapport within out-of-school time programs promotes caring and supportive relationships among children and adults, as well as increases positive and socially appropriate behavior in youth (Beaty-O’Ferrall, Green, & Hanna, 2010). As staff connect with youth, youth in turn feel supported and safe in the program environment. In order to build rapport, staff should develop genuine relationships with youth while remembering boundaries. While it may not be appropriate to share personal information, it is important for staff to build genuine relationships with the youth they work with.

At the Hunter Elementary middle school program, staff build relationships with youth through genuine conversation and mentorship. Staff talk with youth about their day and share hobbies. During one observation, staff talked with youth about their interest in the NFL playoffs and their favorite football teams. Staff also participate in free time activities by playing basketball with the youth, playing

board games and joining in on conversations. As a result, youth report that staff have provided them with someone to look up to and someone whose opinion is trusted.

Establishing Program Culture: Create structure through rules and routines

Every after school program has a program culture, and this culture creates the overall feeling that children will have when participating in the program. The program environment is developed through the program norms that influence youth behavior (Levin & Nolan, 2003). When youth enjoy the program they are attending and feel supported and cared for, their perception of the program tends to be more positive.

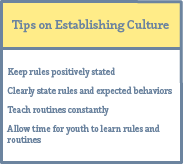

Program culture is developed through rules and routines that help organize expectations for behavior and create a program’s norms. Rules are guiding principles of the program that dictate which behaviors are appropriate (Levin & Nolan, 2003). Too many rules create a restrictive space and a culture of dominance. A limited number of rules are more manageable for youth (and staff) to follow.

Routines, on the other hand, are the practiced ways of doing things in a program. They are more concrete than rules in that they set the tone for expectations regarding tasks, activities, and transitions within a program. Routines create a program system that builds on consistency, and encourages cooperation through knowledge of them (Levin & Nolan, 2003). There are many opportunities for routines in afterschool programs including snack distribution and clean-up, attention getters, moving from one space to another, and sign-in and sign-out.

Communities in Schools, funded to provide OST services at Philadelphia’s William Dick Elementary School, implemented the Creative Kids program, instituting routines that allow youth to move through the program smoothly, confident in their knowledge of what is expected of them. As students dismiss from school, all Creative Kids participants meet in the auditorium for Harambee, a Swahili word meaning “let’s pull together.” During Harambee, youth meet with their groups and engage in chants and cheers while waiting for everyone to arrive. During snack time, various attention getters quiet youth for announcements and table cleanup is completed by all youth. Staff do not have to repeatedly ask youth to comply because they already know the program’s expectations.

Effective Discipline Policies: Promote social skills and self-regulation

Effective Discipline Policies: Promote social skills and self-regulation

Even OST programs that build strong relationships and establish clear program norms may still face challenging behaviors. Staff should provide levels of intervention based on the intensity of the behavior, and the ultimate purpose of discipline policies should not be to control behavior, but to develop social skills and encourage self-regulation (Levin & Nolan, 2003). By slowly escalating interventions, staff give youth an opportunity to correct inappropriate behavior before implementing consequences. First, staff must be proactive in preventing disruptions, such as by giving tasks to bored or disengaged youth. Next, reactive interventions may be required to stop a problem behavior, such as directly appealing for a behavior change. Lastly, when behavior has not improved, a consequence may be appropriate.

Bethune Elementary School’s Safe Haven program, operated by To Our Children’s Future with Health, another funded provider agency within the OST network, includes staff who continually encourage youth to evaluate their behavior and modify it before they impose consequences. During an observation of this program, one youth was observed failing to follow the instructions for an activity. The staff member indicated to the child that this behavior was inappropriate, first subtly, by making eye contact and walking towards the student, and finally by explicity requesting that the behavior be modified, or the student would face a consequence of limited free time. When faced with the consequence, the child changed the behavior and the activity proceeded smoothly.

Preparation and Planning: Keep youth busy and engaged

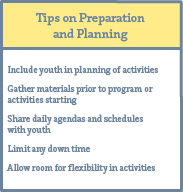

Afterschool staff must adequately prepare for each programming day. Planned activities and limited “down time” keep youth busy and engaged, and limit disruptions. By planning in advance, staff set clear expectations for youth, giving them the opportunity to help monitor time and keep everyone on task. Preparation of activities ranges from planning each aspect of the activity (from the opening to the closing), and gathering all necessary materials prior to youth arrival, to arranging the activity space. Flexibility also comes with planning and preparation because staff can modify activities based on youth engagement each day.

At Boys and Girls Club of Philadelphia, Vaird Unit, funded to provide after school and summer activities for elementary level students homework time is planned prior to youth arrival. Each homework space has designated tables for youth to complete their homework, as well as tables designated for post homework activities. There are sufficient supplies available to use to assist youth with homework such as calculators, pencils, rulers and paper, in addition to academic workbooks, flashcards and educational board games for those who have completed their homework. Youth enter the homework space and immediately know which tables to sit at, and they have all of the materials necessary to complete their homework and engage in post- homework activities. Additionally, at the West Kensington Unit of the Boys and Girls Club of Philadelphia, staff plan activities in advance and obtain all necessary materials for activities, including simple energizers that staff they can readily use when youth need a change of pace in the agenda.

Conclusion

Although youth do not spend the majority of their day in after school programs, their participation clearly supports positive development. It is through classroom management that staff help youth be accountable for their actions and develop relationships. By using these four strategies in programs, providers within the DHS OST system are meeting DHS desired outcomes of improving life skills and improving relationships through positive interactions with peers and adults and teaching youth personal accountability. Not every method works for each program, because no program services the same youth, so programs should design methods that fit their cultures. With practice, staff and youth will be able to work together to create an environment of cooperation, accountability and consistency.