Introduction

Across the world and in all sectors, women remain severely underrepresented and under-acknowledged in leadership positions. In politics, only 24 percent of members of Parliament worldwide are women.1 In work, only 50 percent of women globally are in the labor force, and women on average earn 24 percent less than men.2 Furthermore, in business, only 22 percent of individuals currently holding senior managerial positions in both the public and business sectors are women.3 Women comprise only four percent of Fortune 500 CEOs, and 33 percent of all companies globally do not have any females in senior management.4

However, the status of women in social entrepreneurship importantly disrupts many of these patterns of gender inequality, as the sector has proven itself uniquely capable of empowering women leaders in its own field, and of changing the lives and welfare of all women. Over 40 years and across 92 countries, Ashoka has continuously led the sector with a strong track record of electing and empowering leading women social entrepreneurs as 38 percent of our global network. This rate far surpasses the level of representation and leadership in business and government, among many other fields. Furthermore, this is a particularly dramatic number in light of our high-level criteria for selection, which means that 38 percent of our network represents ideas authored by women and organizations or movements established and led by women.

In this article, we leverage the compelling results of Ashoka’s 2018 Global Impact Study to argue that women in the social entrepreneurship field have excelled and created impact that affects deep and lasting social change. However, we also highlight that women social entrepreneurs face pervasive gender-specific challenges that can disrupt the achievement of their full potential. Furthermore, and more importantly, the insights from the Global Impact Study validate our thinking that success and growth in social impact have been narrowly defined to the neglect of more encompassing descriptions, systematically excluding women social entrepreneurs from being widely acknowledged as successful by the mainstream. The insights within this article therefore tell the story of how leadership and success in social entrepreneurship can and must be redefined from a gender perspective, transforming how women, and indeed all social entrepreneurs, are perceived in the field.

Why Women’s Leadership?

Redefining the metrics of success in social impact is key for increasing the power and the place of women social entrepreneurs. In fact, the two ideas are mutually reinforcing. When we reframe the definition of success in a way that better includes and celebrates women social entrepreneurs, we curate an ecosystem that is more likely to inspire and nurture women changemakers. This increased presence, in turn, inherently leads our metrics closer to a positive frame about the unique ways in which women lead and create social impact.

Ashoka envisions an Everyone a Changemaker World -- a world fit for a new rapidly changing environment, a world where every individual is equipped to create solutions that outpace social challenges. In this world, women -- who represent at least half of the world’s population -- must be fully included. We know that women are disproportionately represented and supported even in social entrepreneurship but do not have disproportionate solutions to the world’s most pressing challenges.

We also know that there are tangible incentives in the clear links between women in leadership and success in social impact. The evidence from our 2018 Global Impact Study reinforces the existing knowledge and Ashoka’s observations and experience from 40 years of working with more than 3,500 Fellows that women are uniquely capable of uplifting the lives of other women, families, and communities. According to the World Bank, women entrepreneurs contribute substantially to economic growth and poverty reduction and are more likely to contribute to children’s education, health, and nutrition.5 Furthermore, women are 45 percent more likely than men to be seen as demonstrating empathy consistently. Among other qualities, women outperform men in inspirational and transformative leadership, conflict management, organizational awareness, adaptability, teamwork,6 and responding to global challenges following crises.7 These same qualities distinctly position women to transform communities and societies, both within and outside of social entrepreneurship.

This article is organized as follows: the preceding section answers the pressing question of why women’s leadership matters for social entrepreneurship. The following two sections subsequently outline the key findings from 2018 Global Fellows Study -- first summarizing the gender-specific challenges faced by Ashoka’s female Fellows, then demonstrating the differences between the impact models generally adopted by female and male Fellows. These differences both improve our understanding and raise new questions around how female and male Fellows relate to their beneficiaries and to their cause to create diverse levels of change. Finally, this article concludes by arguing for a need to reframe the current limited definition of impact and success and introducing Ashoka’s new program, Women in Social Entrepreneurship (WISE), which endeavors to do so.

Gender-Specific Challenges

Ashoka is the largest network of social entrepreneurs in the world, and with more than 1,200 leading women social entrepreneurs, marks the world’s largest resource for knowledge on women in social entrepreneurship. Our 2018 Global Impact Study, Ashoka’s greatest research effort on its Fellows to date, critically tapped that resource and illuminated key insights around the gendered barriers and successes of women social entrepreneurs. The qualitative interviews conducted within Ashoka’s Global Impact study revealed that the most common challenges shared by women Fellows were that their sector was heavily dominated by men, that they were discriminated against for their appearance (particularly if they were also young), that they were not listened to or given decision-making power in group situations, and that fundraising and networking were easier for their male colleagues. Female Fellows often felt underrepresented (either in their sector of work, in “elite” gatherings such as board meetings, or as entrepreneurs), stereotyped (as more “empathetic” and “caring” than their male peers), or simply not accepted. Moreover, the global survey found that women Fellows, despite representing the world’s leading social entrepreneurs, were likely to face barriers in investment and access to funding, discrimination and stereotyping, and industry gender bias and representation.

According to our global survey nine percent of the Ashoka Fellows who reported experiencing gender-specific challenges shared that they had faced financial constraints such as attracting funding and investment as a result of their gender, and the same challenge emerged as a more prominent theme within the qualitative interviews where several women Fellows reported that fundraising and networking were easier when a male colleague was present. Of those who reported gender-specific challenges, 26 percent faced related barriers of discrimination exhibited by a lack of respect or credibility.

“I sometimes have the impression that I have to [put in] more effort to be heard and taken seriously, because my style of expressing myself maybe is more ‘feminine’ and does not always [fit] the more ‘masculine’ types of meetings, pitching events…”

(Female, Europe)

Furthermore, the study found that 20 percent of those who reported gender-specific challenges experienced stereotyping or preconceived notions about gender roles or characteristics, and 13 percent faced challenges in representation, including gender predominance in certain sectors and disproportionate representation in decision-making power.

Impact from a Gender Perspective

At the heart of why women social entrepreneurs remain underrepresented in the “hall of success” are not only the gender-specific barriers that slow or stall their progress, but also and more critically, the limited definition of success that has dominated the sector and systematically excluded women social entrepreneurs from being considered successful by the mainstream. The success of many women social entrepreneurs is made invisible when the prevailing model of success in social entrepreneurship considers impact according to a definition that favors male-dominated notions of broad impact through scaling out and franchising, what I call the fast-food franchising model. That is, the sector has largely copied its metrics of success from the business, development, and academic sectors -- namely number of customers/beneficiaries served, and breadth of area reached. Those inherited “mainstream” metrics continue to dominate among the social entrepreneurship sector and to distort understanding of what it means to scale, neglecting the actual and unique value proposition of social entrepreneurship. In the field of social entrepreneurship, where individuals dedicate their lives to solving major social problems, leading big idea changes, and making the world a better and safer place, it is important to demonstrate, as our survey proved, that women leaders have in fact succeeded and achieved their goals, albeit in a different way than how mainstream male-gendered lenses have traditionally defined success and growth.

While there is increasing knowledge emerging on the different impact models applied by men and women in the for-profit sector, Ashoka’s Global Impact Study results provide a further developed perspective of social impact from a gender lens. The primary motivation for both men and women to become social entrepreneurs is to address a social problem or to benefit the community. This is central to the vision of Ashoka, where we elect as Fellows only those entrepreneurs for whom social change is the core and engine of their work. However, the nature of scaling models and impact between women and men reveals that although the motivation is shared, the manifestation greatly differs. The survey and qualitative interview results demonstrate that social impact enacted by Ashoka’s men and women social entrepreneurs systematically differs in choice of type of growth, relationship with the cause, leadership style, and breadth and depth of scale.

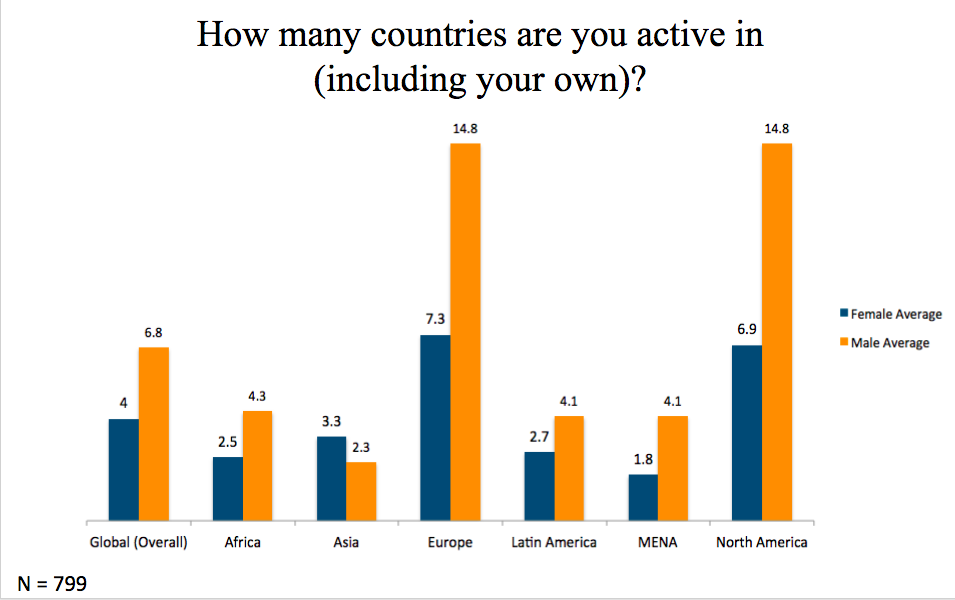

One of the most prevalent findings from our Global Impact Study is that women Fellows tend to spread their idea locally and/or nationally, while male Fellows are more likely to spread their solution on an international level. While women Fellows on average were active in four countries, the global average for men was significantly higher at 6.8.

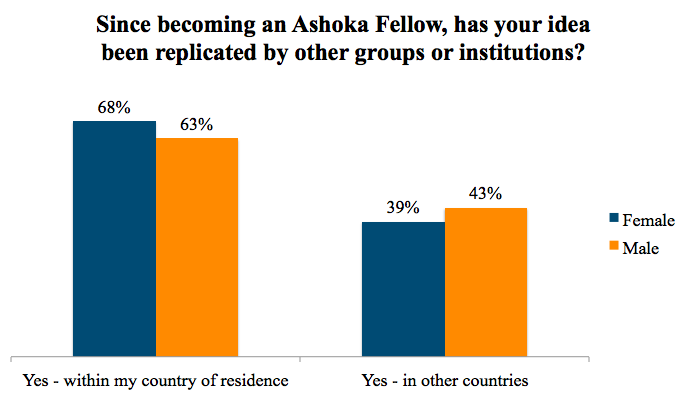

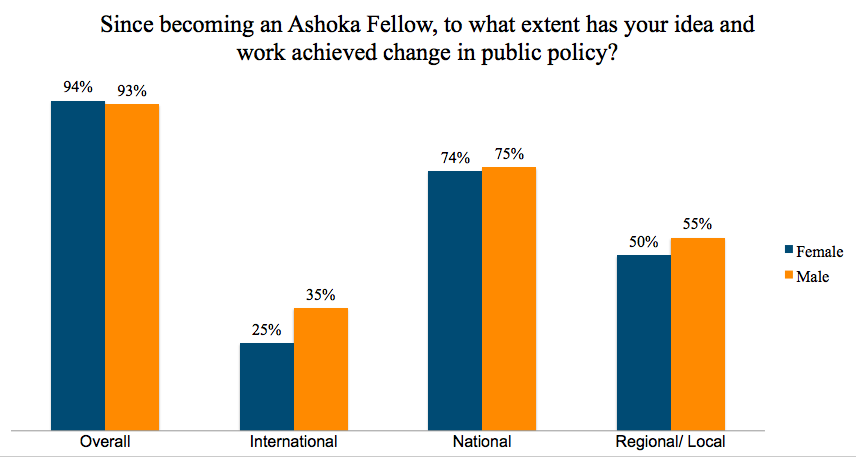

This disparity in international breadth of scale underlies various levels of impact measured by the Global Impact study. For example, while female Fellows reported achieving a similar overall rate of policy change, a higher percentage of male Fellows reported achieving changes in public policy at the international level. 35 percent of male Fellows reported achieving change in policy at the international level, compared to 25 percent of women Fellows. In addition, while female Fellows were more likely to report that their idea has been replicated by other groups or institutions within their country of residency, male Fellows were more likely to answer that their idea had been replicated in other countries.

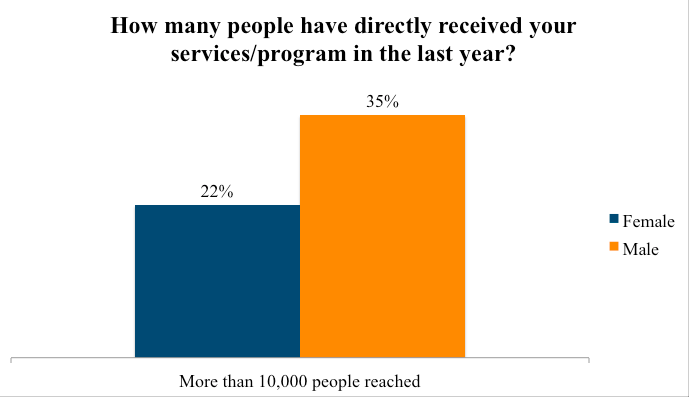

Furthermore, one of the most popular metrics of success in social impact inherited from the private and development sectors is the number of beneficiaries (or customers) reached. According to survey results, 35 percent of male Ashoka Fellows had directly reached more than 10,000 people. Meanwhile, this number had been reached by 22 percent of women Fellows. This clear gap, in conversation with the compelling insights around international scale, provides strong evidence that male social entrepreneurs tend to scale broadly: geographically replicating and disseminating their idea, often through a franchising model that has worked effectively within the for-profit sector.

Meanwhile, the insights from Ashoka’s Global Impact Study suggest that women Fellows are more cause-driven than their male counterparts, which influences every stage of their establishment and scaling. 63 percent of women Fellows have a personal connection to the problem they are tackling, compared to 59 percent of male Fellows. This tendency may be due in part to the greater likelihood of women Fellows, according to Ashoka’s impact survey, who have a personal connection to the social or environmental problem they are tackling. It can also critically explain why women social entrepreneurs may have a greater tendency to scale deeply, prioritizing the penetration of a solution over its expansion.

Meanwhile, the insights from Ashoka’s Global Impact Study suggest that women Fellows are more cause-driven than their male counterparts, which influences every stage of their establishment and scaling. 63 percent of women Fellows have a personal connection to the problem they are tackling, compared to 59 percent of male Fellows. This tendency may be due in part to the greater likelihood of women Fellows, according to Ashoka’s impact survey, who have a personal connection to the social or environmental problem they are tackling. It can also critically explain why women social entrepreneurs may have a greater tendency to scale deeply, prioritizing the penetration of a solution over its expansion.

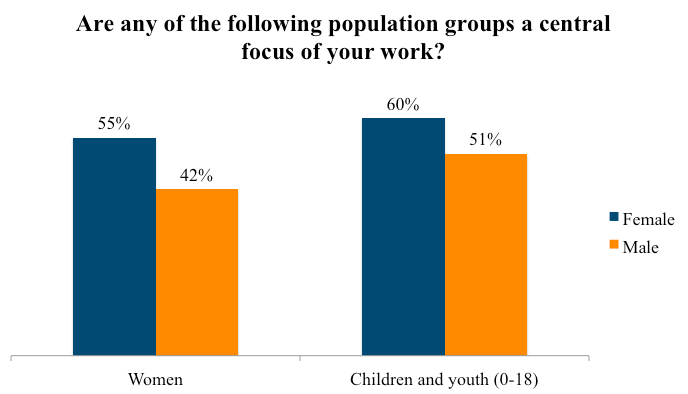

For example, our global survey revealed that female Fellows were not only more likely to work with children and youth (by 60 percent versus 51 percent for male Fellows), but they also are more likely to provide youth with opportunities to start their own initiatives as a core part of their strategy. Carving the minds of youth and affecting their mindsets has a deep and long-term impact beyond the metrics, as they represent the next generation of mothers, fathers, and leaders in all sectors. In addition, female Fellows were more likely to work with women (by 55 percent versus 43 percent for male Fellows), who, in social development, have proven more capable of passing on benefits to their families and communities than male beneficiaries.

The interview results further demonstrated that female Fellows were more likely to be aligned with Ashoka’s EACH strategy in terms of decentralized leadership, empowering young people, and creating changemakers on their teams (affirming the existing knowledge on higher levels of empathy among female leaders).

Moreover, female Fellows were also more likely to directly target patterns of behavior and cultural value within their solution. According to our survey results, 97 percent of Fellows overall reported that their idea focuses to some extent on influencing societal mindsets/cultural norms. Meanwhile, female Fellows were slightly more likely to report that this is core to their strategy (76 percent compared to 73 percent).

Conclusion: The Need for a New Frame -- Scaling Broad vs. Scaling Deep

Because the social entrepreneurship sector has in many ways inherited the success metrics of the private and development sectors, where immediate revenues and physical expansion are widely acknowledged and rewarded, the impact of women social entrepreneurs is often neglected and undercelebrated. However, defining and measuring impact and success by the number of people and countries directly reached fails to address the systematic challenges that preclude women from such achievement, and more importantly, fails to capture the deeper patterns and behaviors that shape the world.

Although it is important to acknowledge, as our global study has done, the gender-specific challenges and disparities that guide variations in impact, it is also necessary to understand that women’s ways of leading differently does not mean leading less impactfully or successfully. In the private sector, “larger” and “scale” are the key words synonymous with success in a field where the strongest business models are replicated and franchised. However, the emphasis and the drive for social entrepreneurship is and continues to be the scaling of impact, which does not and should not exclusively mean larger, broader, or more of the same thing.

Moore, Riddell, and Vocisano in 20158 argued that there are indeed different strategies for the social entrepreneur to have an impact. Scaling up, which is popularly used to mean general growth and spreading, is defined in their research as impacting laws and policy, based on the belief and understanding that structural problems and their root causes can be resolved by creating appropriate laws and policies. Scaling up includes new policy development, but also advocacy to advance certain legal changes and even redirecting institutional resources. Given this definition, a large number of female Fellows have in fact scaled up. Meanwhile, scaling out was defined by the authors as impacting greater numbers of people through replication and geographical dissemination. Finally, scaling deep includes changing relationships and shifting cultural values and beliefs. Through transforming mind sets, value systems, and norms, such impact has a deep and long-lasting impact on a selected community and its future generations. Based on the results of the Global Fellows Study, we now know that women Fellows are more likely to be achieving this type of impact than their male peers. Scaling deep means that the social entrepreneur can generate revenue in different ways, but the focus is on the added value and mind shift that creates a long-term and sustainable impact on the community.

This diversity in impact models reflects the fundamental difference between the private and social entrepreneurship sectors. While the success metric in the private sector remains replication and reach, the more salient measure of success in social entrepreneurship is idea spread, which can be accomplished by scaling up, out, and deep. Indeed, for a social entrepreneur, scaling internationally may not be the highest level of systems change, and a woman social entrepreneur’s choice to scale nationally rather than internationally more often reflects a choice than a challenge -- a choice, for example, to prioritize deep-rooted structural solutions over physical expansion.

Consider the case of microfinance institutions (MFIs). Although female borrowers are by far the largest market for microfinance institutions, only 27 percent of MFIs globally were run by female CEOs in 2008 and the largest MFIs today are predominately led by men. This gap is due in part to the fact that many formative microcredit institutions that were created by women, including my own in 1987 -- the Association for the Development and Enhancement of Women (ADEW) -- were not concerned with physical expansion but rather with penetration. They were more concerned with providing women with access to credit through collaborating with sister organizations and transferring the know-how than with franchising. This pattern has materialized throughout Ashoka’s experience with leading women social entrepreneurs who have excelled in spreading their idea.

Elected in India in 2006, Hasina Kharbhih created the nationally and internationally acknowledged Meghalaya Model, a comprehensive tracking system that successfully brings together the state government, security agencies, legal groups, media, and citizen organizations to combat the cross-border trafficking of children in the porous Northeastern states of India. She succeeded in embedding her model for change in local government anti-tracking operations and today the venture has evolved into a global program that aims to put an end to human trafficking and exploitation worldwide. The Impulse NGO Network has rescued 72,442 women and children across the eight states of North-East India to date, and the countries that India shares borders with, including Nepal, Myanmar, and Bangladesh. As such, Hasina stands as an effective model of scaling both up and out for idea spread and social impact. The replication of her solution worked not through direct expansion or franchising, but predominately through collaboration with local NGOs and government adoption -- creating sustainable, even if less traceable, pathways of her social impact. Hasina’s story also reflects our survey findings that female Fellows tend to work within existing systems to scale their idea, while male Fellows tend to form their own organizations and/or models to spread their idea outside of existing systems.

The cases of women social entrepreneurs leading MFIs and the specific case of Hasina demonstrate the prioritization of a solution -- universal access to micro-credit or reducing child trafficking -- through collaboration, training, and the transfer of knowledge, and not necessarily the growth of their own ventures. This difference between expansion and penetration is at the heart of scaling deep: changing the roots of culture, relationships, and values to enact truly lasting and sustainable change.

The preliminary findings of Ashoka’s Global Impact Study demonstrate that women social entrepreneurs are likely more inclined than their male counterparts to scale deep. Anecdotally through our Fellowship in the Middle East and North Africa, we have also found that women Fellows are more likely to work on sustainable change through future generations, to work deeply within localized communities to change patterns of behavior and enact longer-term impact, and to place influencing societal mindsets/cultural norms at the core of their strategy.

Abla Al Alfy, elected in Egypt in 2013, developed and introduced a new category of healthcare professionals in Egypt -- licensed Child Nutritional Counselors. The guiding objective was to educate and change the behavior of mothers, focusing on a child’s most critical years: the first two. The Egyptian Ministry of Health and Population, persuaded by her success, soon integrated Dr. Abla’s certification process into the public healthcare system. In areas of implementation, stunted development dropped from 21 to 10 percent, and the exclusive breastfeeding rate grew from 13 to 52 percent. In 2015, Dr. Abla began to expand -- not to different countries, but from a child’s first two to first six years of life (during which 95 percent of a child’s brain and physical growth happens). Dr. Abla’s foremost objective remains to achieve the penetration of deep and lasting behavior and culture change in how health officials and young mothers think and act with regards to children’s nutrition, thus affecting the health status of all current and future children in her targeted governorates. As such, Dr. Abla stands as an effective model of scaling up and scaling deep for idea spread and social impact.

How we define success is essential not only because it excludes many social entrepreneurs --especially women -- but also because it limits our understanding and recognition of viable solutions. It hides how positive change through the spread of a new idea can and does happen at different levels. This is the starting point for Ashoka’s new global frontier, the Women’s Initiative for Social Entrepreneurship (WISE): to comprehensively redefine the terms that preclude women social entrepreneurs from being acknowledged for their success and that prevent all social entrepreneurs from creating and growing diverse system-changing solutions.

Works Cited

1 “Women in National Parliaments,” Inter-Parliamentary Union, last updated 1 October 2018, accessed 25 October 2018, http://archive.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm

2 British Council, “Activist to Entrepreneur: The role of social enterprise in supporting women’s empowerment,” 2017, accessed 25 October 2019, www.britishcouncil.org/sites/

3 “The Global Gender Gap Report 2017,” World Economic Forum, 2 November 2017, accessed 24 October 2018, www.weforum.org/reports/

4 “Women in Top Leadership Positions,” Market Inspector, last modified 22 November 2017, accessed 25 October 2018, www.market-inspector.co.uk/blog/2017/

5 “Female Entrepreneurship Resource Point - Introduction and Module 1: Why Gender Matters,” World Bank, n.d., accessed 24 October 2018, www.worldbank.org/en/topic/gender/

6 “New research shows women are better at using soft skills crucial for effective leadership and superior business performance, finds Korn Ferry Hay Group,” Korn Ferry, 4 March 2016, accessed 25 October 2018, www.kornferry.com/press/

7 Georges Desvaux, Sandrine Devillard, and Sandra Sancier-Sultan, “Women leaders, a competitive edge in and after the crisis, Women Matter 3, McKinsey & Company, April 2010, accessed 25 October 2018, www.mckinsey.com/~/media/

8 Michele-Lee Moore, Darcy Riddell and Dana Vocisano, “Scaling out, scaling up, scaling deep: strategies of non-profits in advancing systemic social innovation,” The Journal of Corporate Citizenship 58 (2015): 67-84.

Author bio

Iman Bibars is the Regional Director for Ashoka Arab World (AAW) which she launched in 2003. Iman is a Leadership Group Member and Global Diaspora Leader in Ashoka. She is the co-founder and chair of ADEW, a CSO providing credit and legal aid for impoverished women. With more than 30 years of experience in strategic planning, policy formulation, community development, and project design, Iman has dedicated her life to working with marginalized and voiceless groups -- female heads of households in Egypt's poorest areas. Iman has also worked with UNICEF, Catholic Relief Services, CARE-Egypt, GTZ, and KFW. Iman holds a PhD in Development Studies from Sussex University and a BA and MA in Political Science from American University in Cairo. She was a Peace Fellow at Georgetown University and a Parvin Fellow at Princeton University. Iman has been featured in several national and international press outlets and also authored several books.