Immigration Services Fraud -- What It Is

Our nation’s immigration system is notoriously complex and most immigrants require immigration legal assistance to navigate the complicated system. Making permanent or legalizing one’s immigrant status means better jobs, a more stable future, and for many, relief from living under the shadow of fear. But in Philadelphia, as in many other cities, there are simply not enough immigration attorneys and legal aid organizations to meet the needs of the growing immigrant population. Unfortunately, a supply of fraudsters has sprung up to exploit the demand and immigrants’ fears and dreams.

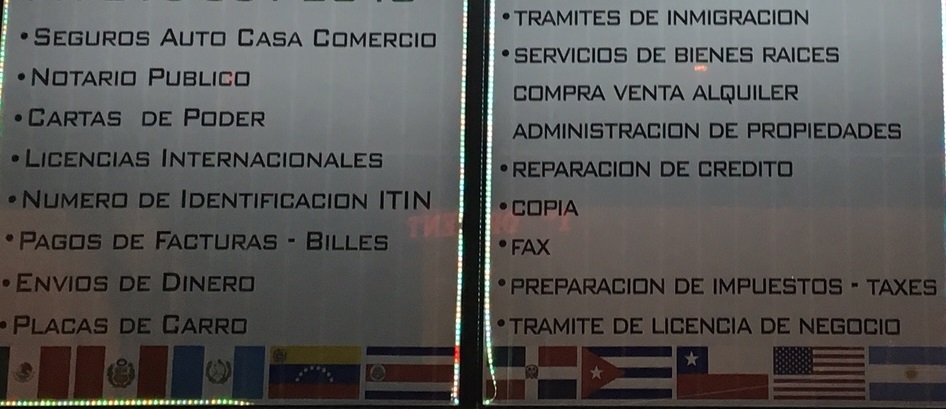

The fraudsters often call themselves “multiservice” businesses and offer money transfers, interpretation, international calling cards, and other immigrant-targeted services in addition to “immigration services.” Others advertise themselves as a “notario publico,” or “notary public,” a term that is used in many Latin American countries to refer to a licensed attorney, although in the U.S. most notary publics are not attorneys. Such businesses are unequivocally engaging in immigration services fraud; and, while the unauthorized practice of law is a crime, the bigger problem for defrauded consumers is that the consequences of making mistakes or submitting the wrong application can be devastating.

Unsuspecting consumers often pay up tens of thousands of dollars for what they believe are legitimate services, only to find out later that they do not actually qualify for any legal status at all. Victims and their families may struggle for years after their investment in what they believed was a pathway to a more stable future turns into a financial nightmare. Longtime green card holders seeking to become U.S. citizens or U.S. citizens wanting to sponsor loved ones can also face irreparable harm to their immigration cases: losing a benefit they were once eligible for, facing long delays in processing an application, or being permanently barred from seeking immigration benefits in the future. In the worst cases, fraud victims’ attempts to do the right thing to gain legal status can result in deportation.

Philadelphia Ordinance: The Role of Collaboration

Despite the fact that immigration services fraud is a common problem, there are only a handful of programs across the country that focus on this issue. In Pennsylvania, the first program was the Notario Fraud Project (NFP), which began in 2012 as a law student project run by Vanessa Stine. In its early days, the NFP interviewed victims of immigration services fraud, conducted outreach, and participated in public presentations. As an attorney at Friends of Farmworkers (FOF), Stine continues the NFP’s work. Through creative litigation strategies, effective community education, and an increased network of assistance, the NFP has recovered more than $175,000 on behalf of victims, educated nearly 10,000 consumers, and obtained three court injunctions.

While Stine was developing the NFP, Miriam Enriquez, a longtime Philadelphia prosecutor, had been researching the issue while at the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office. When Enriquez began working as the Director of Legislation and Policy for then-Councilman-at-Large Dennis M. O’Brien in 2013, she saw an opportunity for City Council to help immigrant victims avoid fraudulent schemes and to protect their pathways to citizenship.

Enriquez and Stine’s paths inevitably crossed and they began working together in late 2013. They reached out to advocates and officials in other municipalities to learn about the ordinances that already existed. As a result of this research, City Councilmembers O’Brien and Maria Quiñones-Sánchez introduced and successfully passed a resolution to hold a hearing about immigration services fraud in Philadelphia. Enriquez and Stine drew on their community contacts to help organize the hearing in March 2014, where victims of fraud, along with City officials and advocates familiar with this issue, provided testimony. After this hearing, Councilman O’Brien introduced a bill intended to curtail immigration services fraud by regulating non-attorney businesses that offer immigration-related assistance.

Over the next nine months, City Council staff, various City departments, and a team of non-profit advocates, all coordinated by Enriquez and Stine, went through dozens of revisions of the proposed ordinance. While the intent of the ordinance was clear, there were some challenges in fleshing out the practical details, such as determining who would enforce the ordinance because Philadelphia does not have a consumer protection agency. Businesses are instead regulated by the Department of Licenses & Inspections (L&I), which primarily enforces construction, property, and fire codes and oversees permit and license issuance. O’Brien’s staff and advocates sought input from L&I on designing an ordinance that would be compatible with L&I’s existing enforcement procedures.

Another challenge was addressing how businesses should be regulated. While initial drafts of the ordinance included a licensing component, during the revision process some members of City Council’s Licenses & Inspections Committee, as well as L&I, the American Immigration Lawyers Association, and others, expressed concern that licensing could inadvertently legitimize the idea of non-attorneys providing legal services. After discussion, everyone involved agreed that a registration-only requirement was a better solution, and a new -- and nearly final -- draft emerged.

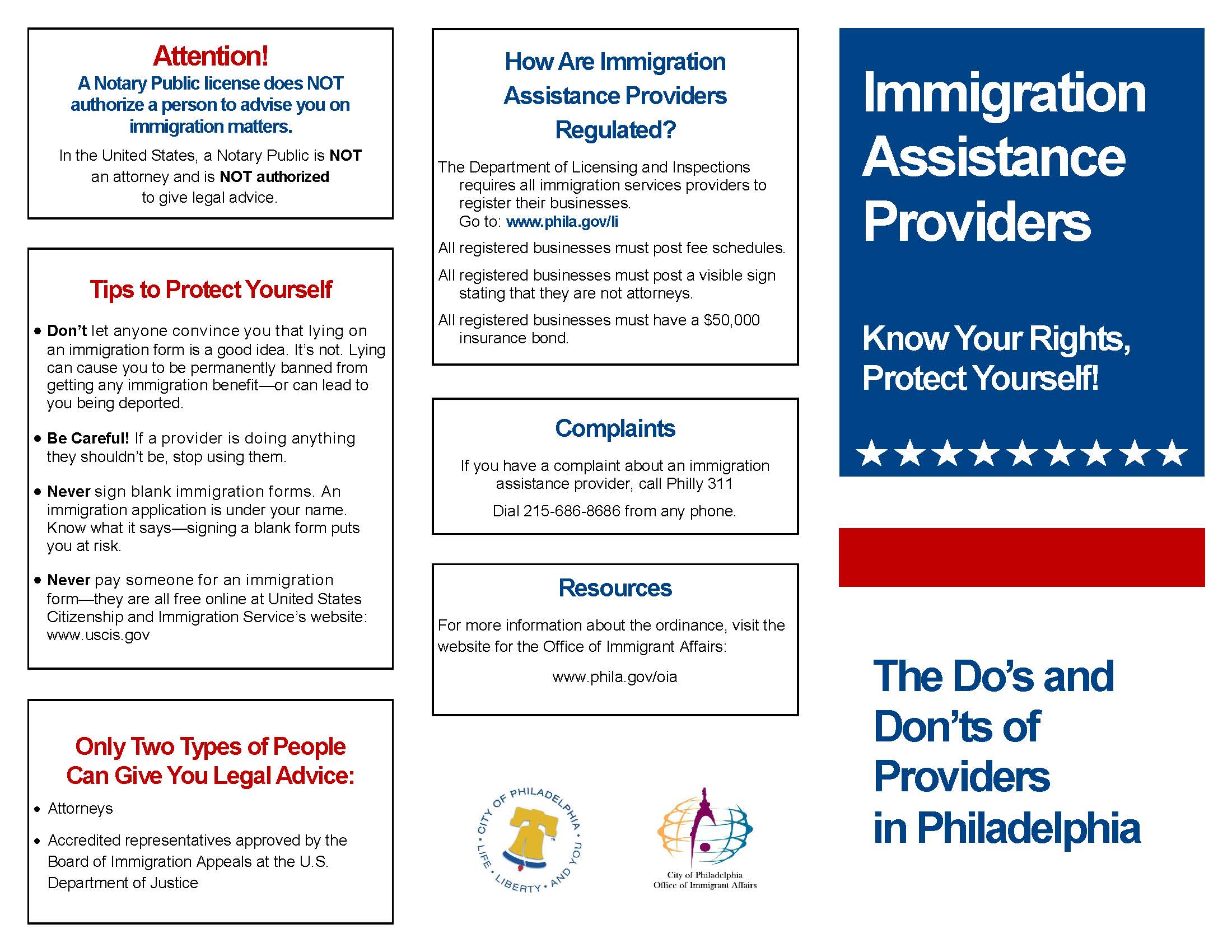

Click here to view the second page of the brochure.

In December 2014, City Council unanimously passed the ordinance, which is now codified as Philadelphia Code Section 9-634. The final ordinance protects consumers by 1) mandating that immigration service providers make certain disclosures, 2) prohibiting particular conduct, and 3) assigning liability. The mandated disclosures require these businesses to notify consumers that they are not authorized to provide legal services through on-site signage, in advertising, and perhaps most notably, through a brochure that must be disseminated to all customers and which is essentially a customer bill of rights. The prohibited conduct complements Pennsylvania’s unauthorized practice of law and consumer protection statutes by prohibiting businesses from giving legal advice or engaging in other deceptive conduct, like making guarantees about case outcomes or claiming that they have special connections to government agencies like the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Finally, liability for non-compliance ranges from cease operations orders to fines and civil penalties. There is also a private right of action that victims can use to seek injunctive relief and damages.

Example of a business in Philadelphia that offers immigration assistance.

Collaboration across City departments and non-profit partners has continued with the implementation of the ordinance. From developing the brochure to training staff in various city departments, Enriquez, who is now the Director of the Office of Immigrant Affairs with the City of Philadelphia, and Stine continue to work together. For instance, Enriquez and Stine recently trained L&I inspectors on the ordinance and 311 operators on processing consumer complaints against notarios. Implementation has also brought in new collaborators, including the Sheller Center for Social Justice at Temple University Beasley School of Law, which worked with FOF to submit test complaints. These complaints then became the focus of the city’s pilot program for enforcement.

The result of this extensive work is that victims of fraud now have some redress for their injuries. The Philadelphia ordinance has already been replicated by the City of Reading in Pennsylvania, and it is also being looked to as a model by municipalities like Atlanta, Georgia, Denver, Colorado, and San Jose, California.

Collaboration Works: Looking Back and Moving Forward

The story of Philadelphia’s immigration services fraud ordinance shows that municipalities can leverage community collaboration to protect immigrants, while community partners can maximize the impact of their work and better protect their clients through city collaboration. Lessons were of course learned on all sides, including:

- Be humble and learn from others. Be open to feedback, even if that means changing something that was your idea and the compromise results in something different from your original ideal. Likewise, learn from and improve on the work that others have already done.

- Legislative change takes patience and persistence. Legislative changes, even at a local level, take time -- a lot of time. Community partners should understand this and continue moving forward despite the inevitable setbacks. Remember that every small step forward is still progress.

- Community partners are important. Community partners are critical for meaningful, local legislative change because of the trust and expertise they bring. For example, victims of immigration services fraud are generally much less fearful of reaching out to non-governmental organizations than to, say, a prosecutor’s office.

- City infrastructure matters. Any municipality considering similar measures should plan carefully around their local governmental infrastructure and allocating adequate resources for meaningful implementation and long-term success.

The sustained collaboration between the City of Philadelphia and community partners has created a more immigrant-friendly policy during a time in which anti-immigrant rhetoric permeates the public sphere and increased immigration enforcement has caused fear and family separation. It is during such challenging times that collaboration is more important than ever, as it is precisely when local policy changes can mean the most.

Author Bios

Vanessa Stine is a Staff Attorney with Friends of Farmworkers, Inc., a statewide legal aid organization that has been supporting low-wage workers as they pursue economic and social justice for nearly 40 years. Ms. Stine joined FOF as an Equal Justice Works Fellow in Fall 2014 and is now a Staff Attorney at FOF. She graduated Order of the Coif from Villanova University School of Law. She also has a B.A. in Sociology/Anthropology from Lewis & Clark College.

Miriam Enriquez is the Director of the City of Philadelphia’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (OIA). Before joining OIA, Enriquez served as City Councilman-at-Large Dennis M. O’Brien’s Director of Legislation and Policy, where she was instrumental in crafting and passing legislation to protect consumers of immigration services in the City. Prior to her work on City Council, Enriquez served as an Assistant District Attorney at the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office for seven years. She advocated for countless victims and successfully prosecuted thousands of misdemeanor and felony cases, impacting every city neighborhood. Enriquez was a pioneer prosecutor in the Gun Violence Task Force, where she fought tirelessly against gun trafficking in Philadelphia. Enriquez received her B.A. with distinction from George Mason University and her J.D. from The Dickinson School of Law. Enriquez was born in the United States, but spent much of her childhood living in several different Latin American countries, including Nicaragua, her family’s country of origin.