Summary

Corona Foundation is a family second-floor foundation that has been working for the improvement of Colombia over the past 56 years. In 2011, the foundation assumed the second floor role and started working under a strategy that enables the monitoring and learning from initiatives and creating models that can be replicable on its two lines of action: Education oriented to Employment and Education for Participation. After nearly a decade on these topics, some lessons can be included in the development of the concept of the Model of Inclusive Employment.

Overcoming poverty has always been one of the most important tasks of social policy. Including populations that do not have entry into the labor market is also a challenge, especially in low- and middle-income countries. Colombia is not an exception.

With this in mind, in recent years countless initiatives have been implemented aiming to incorporate vulnerable populations into the labor market. Different public and private actors have developed initiatives with varied results. These actors have been local and national governments, international cooperation entities, business and family foundations, NGOs and associations, among other actors interested in promoting labor inclusion.

Through these years, initiatives as programs, projects, or active labor market policies, have been implementing different approaches and have achieved diverse results, always seeking to find ways that allow its population to consolidate mechanisms for income generation, hopefully autonomous, especially by those segments of the population from which social mobility is expected. Despite the efforts, it was a promise that could not be fulfilled for the majority of the beneficiaries of these initiatives.

This article exposes 10 of the main lessons learned by the Corona Foundation1 in recent years, through closely monitoring initiatives implemented in Colombia since 2010, and the generalities of the framework developed from these learnings of the Inclusive Employment Model. The text shows some examples of concrete actions developed from the learning described. At the beginning a general context of education, training, intermediation, and employment is presented.

Foundation Corona’s team.

Credit: Corona Foundation

General Context

Schools are not performing as they should. The probability of entering and staying in the formal labor market is strongly related to the possibility of being a high school graduate. Whoever completes high school has twice the probability of reaching the labor market. According to the survey, “Transition from School to Employment” (Transición de la Escuela al Trabajo (ETET)) conducted by the International Labor Organization (ILO)) “when considering the level of scholarship it is clearly observed that those with higher education (university or not university) are more likely to complete the transition. This is due to the fact that young people who follow post-secondary studies begin their transition at higher ages and in general, they are more likely to be quickly inserted into the labor market, especially in satisfactory jobs” (ECLAC - ILO, 2017). In Colombia, completing secondary education is associated with an increase in labor income of 16 percent compared to not doing so. The gap in the informality rate grows to 19 percent between workers with high school degrees and workers who didn´t complete their high school degree (Sánchez, Munari, Velasco, Ayala & Pulido, 2016).

Additionally, the difference in the average labor income between people with secondary education and people with a higher education in 2018, was 203 percent (FILCO, 2018). However, dropout rates are very high, despite the important advances in cities like Bogotá. More than 21,000 early education children and young people drop out of school in Bogotá each year, with nearly 15,000 in a city like Medellín and 6,000 in a territory like Urabá2. In many territories, the reality is that there are more students who drop out than the those who graduate every year.

In addition to completing middle school, the quality of the education plays an equally important role. Unfortunately, the few who graduate do so with serious flaws. This is clearly reflected in the scores achieved by senior students in state tests (Saber 11 Test). The national average in Saber 11 barely reaches 262 out of 500 possible points. In cities like Cartagena the average is only 247 points, while in Buenaventura only 25 percent of the students have results above the national average. Even worse, if we compare ourselves internationally, in the PISA tests (2015) we are ranked 56 in reading, 63 in mathematics, and 59 in science among 72 countries evaluated.

When analyzing the results by type of educational institution, we find that in the case of math, private schools perform better than urban and rural public schools. However, these results are equivalent to a lag of two years of schooling compared to the OECD average, which in the case of official urban institutions grows to 3.3 years and in rural ones to 3.9 years.

In post-secondary education, things aren’t improving. The offerings in Colombia have countless denominations and categories that in their state of disorder are still the best reflection of the chaos at this stage. A person looking for training options can either be an operator, assistant, technician, or technologist, but this offering does not have adequate mechanisms of quality assurance and labor market relevance, generating an offer that it is not standardized by levels, with different alternatives of duration, structure, certification, and so on. This implies, among other things, that neither people nor employers understand and therefore value this training. Of the total higher education offerings -which include university, professional technique, technologist, and technical and technological specializations, only 24 percent of the entities have quality accreditation. In addition to this, of the total offered trainings as auxiliary, operative, labor technician, including SENA3 technician, only 10 percent of the entities and 25.5 percent of the programs have quality certification (SIET, 2018) through mechanisms with a more administrative approach to assure quality education.

This is certainly the cause of almost one out of two university students and two out of three technical training students abandoning their studies. In the work carried out by the Corona Foundation in different parts of the country, human talent officials repeatedly say that they do not know or understand the different types of training and their relationship with the different positions in the company. The ignorance and level of misinformation of young people and their families is also evident, as they do not understand the existing education alternatives.

In the role of labor intermediator, the panorama is not encouraging either. The country created a network of entities responsible for bringing labor supply and demand closer together, which today reaches nearly 360 entities and 800 attention points around the country. This network of public employment service providers, which includes public and private providers, accounted for three million people and 120,000 vacancies in 2018.

Even so, in eight years of operation of the mechanism, the country does not have yet consolidated information of the entire service offerings or the detail of job seekers and vacancies, meaning, a count of beneficiaries per consolidated single user, and even the microdata of the beneficiaries of each of the financed activities.

Nor can strategic decisions be made. Even today there is no estimate to determine the demand for intermediation services, an estimate of progress in coverage, nor an estimate that allows us to understand the reach of the number of providers and their operational capacity, required according to the needs of each territory and key to determining the deficit or oversupply of the labor offerings in at least the main cities of Colombia.

The offer, financed with public resources, allocated about $364 billion Colombian pesos (Superintendencia de Subsidio Familiar, 2018) in group sessions of orientation and training to job seekers, and only achieved the employment of 362,000 people out of 1.7 million who were registered.

But perhaps the main problem in the intermediation offerings is associated with the fact that the processes between supply and demand are not being done by competences, due to the almost null structuring of vacancies and profiling of candidates according to competences. It has been found that, by not doing so, the pre-selection and selection processes still resort to a second plan in which filters such as the requirement of previous experience and level of education are applied, and not a precise type of training; as well as security tests, interviews in which prejudices are evident, among other practices that do not guarantee the selection of the most productive candidate for the vacancy, but that generate significant discrimination impacts.

Finally, in the case of employers, the picture agrees with the above. The latest available DANE4 survey shows that 52.6 percent of industrial companies, 65 percent of commercial companies, and 25.3 percent of service companies do not have a human resources department. This creates gaps in the quality of the human talent processes of the country's companies, which generates an immense impact on the productivity and equity of the labor market. An example of this weakness, 78.8 percent of the industry, 86.4 percent of commerce, and 56.4 percent of the service companies do not have a talent scheme regarding competencies; in practice, most of the companies in Colombia are not clear about the competencies required to perform in each of their positions. If a company does not have that clarity, it does not have the capacity to effectively evaluate performance, define vacancy profiles, select new employees, or develop results-based wellness programs.

Productivity growth has been a slow process and is quite low. The low productivity associated with human talent finds one of its main causes in the human talent processes.

Lessons learned

This overview demonstrates that the preparation of people, the quality of employers, and the connection between them has shortcomings of quality, access -- permanence, and relevance. At the end, this is manifested in entire segments of the population that face greater barriers to access and remain in the formal labor market, with greater sharpness in some territories. While general unemployment is close to 10 percent in Colombia, it is estimated that for women the rate reaches 14 percent, for young people 17 percent, for Afro Colombians 19 percent, for the victim population 45 percent, and that of people with a disability to more than 70 percent. Even worse, youth unemployment in a territory like Urabá can exceed the national average by 30 percentage points according to available estimates.

Under this scenario, it is very difficult to assume that people in vulnerable segments, who have managed to overcome poverty or are in the process of doing so through subsidy policies, could find permanent and autonomous income-generating mechanisms, and therefore can consolidate or achieve significant progress in social mobility through employment. What should be done?

First, from a systemic vision, it would require the implementation of a set of simultaneous actions to act comprehensively. This means that actions aimed at improving the training of people, improving the conditions of employers, and improving the mechanisms of connection between the two must be implemented; always from an equity and productivity perspective. This means that the efforts that are applied through initiatives cannot focus exclusively on one of these three aspects. For the above mentioned, the actions implemented by the government must integrate the efforts of the education, training, and employment sector offices, which unfortunately usually work in an unarticulated manner.

Second, both corrective and preventive actions must be taken. In a city like Bogotá, for example, more than 20,000 young people leave school every year. This adds to the more than 300,000 young people who do not study or work, and the more than 400,000 who work in informal conditions. With these numbers, it is insufficient to implement programs that reach only hundreds of beneficiaries annually. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the importance of preventive actions, for example, to mitigate desertion; as well as the role of coordination between actors in order to increase the results exponentially.

This leads to a third learning; that it is much more cost-effective to work with the existing institutions and strengthen it, than to allocate all resources to parallel and temporary offers of services. The initiatives should focus their efforts on improving -- not duplicating or replacing - the role of schools, vocational training institutions, and employment centers.

A fourth learning is that the implementation of corrective actions should be contemplated mechanisms that allow people who are facing barriers to entering the labor market to not only enhance their labor competencies but also level up their shortcomings in basic school skills. This takes time, particularly when the gap is wide or when it requires a very strong component of socio-emotional skills.

In this sense, a fifth learning is that the short pathways offered to vulnerable populations are only effective for some segments of the population that have a very small gap in their levels of school and work skills. Offering short pathways to vulnerable populations in general, will only benefit the small segments of the population that did not need the program to reach the labor market. This becomes evident when initiatives increase their beneficiary goals or the number of cohorts, who quickly run out of beneficiaries or must make great efforts to reach new people and meet their goals.

Likewise -- as a sixth learning -- that the actions implemented with employment centers and especially with employers, cannot be centered on the referral of candidates or bare sensitization. When inclusive employment initiatives develop and incorporate better mechanisms to assess and foster human talent processes in employment centers and companies, the chances that the selection, recruitment, performance evaluation, and career plan processes are carried out properly will increase, and consequently this will impact equity and productivity. This brings with it that the work within the areas of guidance and business management in the employment centers, and the areas of human talent in the companies becomes more important compared to the traditional approach of vulnerability and social responsibility.

Seventh: Another learning that emerges from the previous points is that it is necessary to implement long-term mechanisms that allow offering better services and pathways and facilitate the structuring of collective impact exercises that work towards a medium- and long-term vision of the territory, consolidating lessons learned oriented to reach territory level results.

Eight: The allocation of most of the resources from governments, cooperation, and private entities to individual short-term projects, which start from scratch, offer parallel services that double the existing offer, and are oriented to financing activities instead of results, that won´t translate into the required outcomes. The catwalk of project after project financed more with the pretense of being the best remembered, with more beneficiaries, advertised, etc., than the most effective, will contribute to those that continue without real opportunities.

Until last year, the largest projects financed with public resources during the last five years added up 1.3 billion Colombian pesos (Sibs.CO, 2019), without the possibility of evidencing results for the beneficiaries, beyond coverage in certain services that in most cases are ineffective in their promise of entry and permanence in the formal labor market and sustainable social mobility. The results that are shown as effective, generally intend to demonstrate the relationship between training and the probability of labor inclusion, as was discussed at the beginning of this paper.

A ninth learning is the need to structure better mechanisms for allocating resources, to initiatives that are results oriented. These mechanisms would help those who traditionally execute these resources to focus their actions more effectively and for the same, aspects such as preventive actions, institutional strengthening, the design of more robust routes that level gaps in hard and soft school skills, collaboration with third parties, and efficiency would have more room.

Finally, a tenth learning; is necessary to have an orientation towards deeper measurement in the initiatives. If measurement is not incorporated in the implementation, besides the headcount of beneficiaries and activities, it will be difficult to move forward in the identification of the best practices, the best initiatives, and to that extent, in learning as an ecosystem. This learning should allow the progressive implementation of mechanisms aimed at investigating the results of the initiatives, which do not always require the implementation of costly ex-post impact evaluations. The incorporation of well-designed measuring instruments is extremely useful, in the components that the initiative´s intend to foster, from the level of information of the participants to the development of technical skills, even improvements in socio-emotional skills.

Depending on the strategy, the incorporation of measuring instruments makes it possible to identify progress through before and after schemes, or the improvement degree in different approaches. The design of evaluations, with adequate randomizations and control group definitions, allows a more certain attribution of the improvements -- or not -- achieved by the beneficiaries, and a greater notion of the relationship of each of the components towards the final result. It is important to quickly correct the lack of use of appropriate measuring instruments by component, and progressively, the design of impact evaluations. In addition to improve the measurement of interventions, a good practice has been to incorporate tools that allow managing the performance of different actors. In this way, it is possible to collect information and assess what works and what does not work during the interventions, and make decisions during the development of the project, which allows approaching better results.

Framework. The Inclusive Employment Model:

These learnings outline a conceptual map of inclusive employment and highlight some of the main reasons why inclusive employment initiatives do not achieve intended results of reducing the gap between the unemployment of some populations and general unemployment. For this reason, the employment of vulnerable populations has not been effective in practice and the results in social mobility and overcoming poverty from employment has been too low, considering the important resources invested in the country over the past years.

Cooking Class. Pact of Productivity.

Credit: Corona Foundation

These lessons should allow those who currently implement or design new inclusive employment initiatives in the future, to wonder if the way they are structured consider the lessons learned in recent years or if, on the contrary, they reproduce some of the shortcomings thanks to which the initiatives are mostly ineffective.

To promote this reflection, the Corona Foundation together with the Andi Foundation and AcdiVoca structured an inclusive employment model. The Inclusive Employment Model is at the same time a conceptual framework that consolidates the permanent learnings generated in the different inclusive employment initiatives, as well as a tool oriented to strengthen the design or implementation processes of different kind of programs, projects, and active labor market policies, and accelerate the connection, efficiency, and results in the territory.

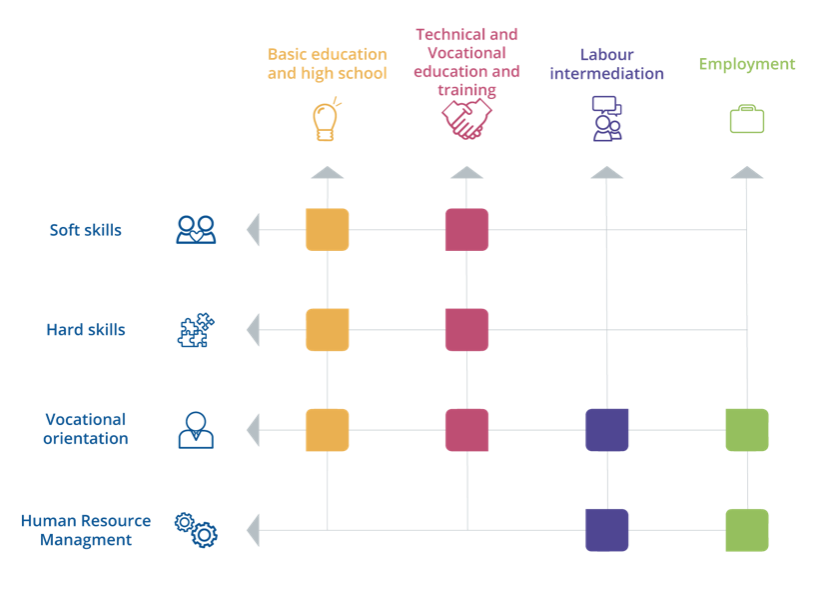

From an overview, the bulk of actions required to reduce the barriers that most affect the probability of accessing and remaining in the labor market can be located in a matrix of stages (columns) and components (rows). The stages are the different points of a pathway people transit from education to formal employment, and in turn the components allow visualizing the themes that hold the most important barriers.

*Components-Stages Matrix. Inclusive Employment Model developed by Corona Foundation, AcdiVoca, and the Foundation of the National Business Association of Colombia (Fundación ANDI), 2016.

This exercise also allows us to propose 10 packages (blocks) of actions around which efforts must be made in each territory. Because of the magnitude of the problem, it is impossible for a single project or program to cover them entirely. A crucial point to understand the model is to read each package (block) through preventive or corrective actions. For example, if each person must have minimum levels of academic skills such as literacy and numeracy (action number 1 in the next graphic), this can be developed by strengthening the teaching processes in primary or secondary basic education, reinforcements in secondary education before leaving school, or through leveling and in some cases validations with people of more advanced ages who want to reach the labor market.

* 10 main packages of actions in the territory. Inclusive Employment Model. Corona Foundation, 2019.

The structure of the Model is complemented by the analysis of four action levels. These allow us to visualize the different ways how each of the key points of the strategy can be addressed. For example, the orientation of young people in the school stage can be done through afterschool programs (action level 1), fostering school capacity to offer vocational orientation (action level 3), or through public policy incidence on public resource allocation or enhancing the frames of the Ministry of Education and local secretariats (action level 4).

* Action Levels. Inclusive Employment Model developed by Corona Foundation, AcdiVoca and Andi Foundation, 2018.

Productivity Pact.

Credit: Corona Foundation

Initiative and Actions

Based on this structure, operational drivers and other key elements are permanently defined and updated, such as monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, the themes under each component for each stage, key methodologies and tools, the tracking of the service provision to particular populations, and mechanisms for results-based financing, among others. Likewise, the ecosystem of more than 50 cities in Colombia is mapped, the best practices, systematizations, and evaluations that are held outside the country; also under the model join efforts with allies such as the ANDI Foundation, AcdiVoca, Teach for Colombia, among others, are carried out to develop tools, methodologies, and deepen learning to constantly feed the model. Some examples are:

Social Impact Bonds Project, Results-based Financing Model

Corona Foundation, together with its allies: The Innovation Lab (IDB-LAB), from The Interamerican Development Bank, The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation and State Secretariat for Economic Affairs, The Social Prosperity Department from the Colombian Government, The Mario Santo Domingo Foundation, and Bolivar Davivienda Foundation, have joined efforts and their institutional skills to develop the Social Impact Bonds Program in Colombia (Sibs.co). Within this program, the first Social Impact Bond (SIB) in a developing country was implemented.

Social Impact Bonds are a results-based financing model that articulates the government, the private sector, and social organizations in the development of innovative and effective alternatives to face social challenges, and whose social innovation condition the co-payers support payment to the fulfillment of the previously agreed results, and not to just activities necessary to achieve the results. This program allowed results, not only in terms of inclusive employment, but also all-around learning about what the results are that the system should measure and the tools available to do so.

A mapping of the ecosystem of programs, focused on inclusive employment, carried out by this program, allowed us to understand that, of all programs focused on inclusive employment, a very small portion use the social security contribution information system in the country (PILA) to monitor and validate their results. In addition, the program has also made evident that it is not only important to measure the management of the projects and the placement they achieve, but also it is essential to understand labor retention of this population, for a cost-effective approach, and for the formulation of appropriate public policies (Sibs.CO, 2019).

This project has also made important contributions by building and implementing a Performance Management Platform that allowed the individual information of each participant to be captured along the intervention pathway. The success of this platform to collect information for decision making processes during the development of the project, not only accounted for innovation data in public policy but led to key actors, in countries like Argentina, to replicate this good practice.

Promotion of Inclusive Employment in Companies (NA2-T4-C4 Guide)

As it has been shown, it is important that companies improve their institutional capacity to hire, in a proper way, people from vulnerable populations. It is true that progress must be made so that people are prepared suitably for companies, however, no matter how much the processes of prior preparation and intermediation within these populations are adjusted, it won´t be enough if the companies have discriminatory actions -- even without knowing it -- in their human talent processes. It is very important to keep in mind that the generation of inclusive employment does not seek to hire workers who do not contribute to the productivity of the company; on the contrary, it seeks to take advantage of the potential of people who have traditionally been excluded from the labor market to make their work profitable for companies. The goal is to find suitable people for the right positions. Some of the benefits for companies are the improvement of productivity, national and international recognition, the reduction of costs due to tax incentives, the reduction of staff turnover, the improvement of the working environment, and the construction of a more inclusive country, among others.

This is why Corona Foundation, ANDI Foundation, AcdiVoca, and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) designed the "Guide for the Promotion of Inclusive Employment in Companies.” This guide aims to promote inclusive employment for vulnerable populations in Colombia by fostering the human talent processes of companies and the creation of inter-institutional alliances.

The document is structured in six chapters in which the most important concepts in Inclusive Employment are explained, why it is worth generating inclusive employment, the role of the company in this task, the moments in which the company can act before, during, and after hiring and the recommended action plan, as well as how to maximize business results through partnerships with other actors. The document provides practical and simple tools for generating inclusive employment among others.

Promotion of Inclusive Employment for International Cooperation

This tool was created to help contextualize the different international actors that decide to invest resources in Colombia aimed at contributing to the inclusive employment of vulnerable population. With the guide and its different chapters, international actors are able to know in depth the context and will have tools and knowledge about the employment ecosystem in Colombia to better focus their resources. This is a useful tool as it allows discovering the Colombian context and strengthening its actions through any of the cooperation modalities established for the country.

This document aims to provide guidelines for international cooperation organizations interested in promoting inclusive employment, propose actions for the inclusion of vulnerable groups, encourage the creation of alliances for the promotion of labor inclusion, and publicize the Inclusive Employment Model for Vulnerable Populations.

Promotion of Vocational Orientation in Educational Institutions (NA2-T1-C3 Guide)

This is a guide for teachers, to give them tools to guide orientation processes in middle school. The methodology of vocational orientation helps to support young people in their process of self-awareness, knowledge of the world of education and training, and knowledge of the world of employment. The National Ministry Education recognizes these three as the central dimensions that build together vocational orientation (Life Pathways: support manual for vocational orientation, first edition 2013). In this sense, the methodology focuses on the identification of their dreams, interests and abilities, but also on providing them with suitable information about training options and the labor market, which allows them to recognize realities and opportunities within the territories they inhabit.

The methodology of vocational orientation in academic secondary education works with young students from the last three grades (9th-11th), as this is the moment when they begin to make decisions about the professions or trades, they will perform in the future. This moment in their life means for them the beginning of their transition to the adult world, where, in accordance with their interests and the construction of values and identities, they establish an internal exchange or debate relationships with a range of options that they as youth can identify.

Conclusions

It is very important that the multiple efforts developed in recent years in inclusive employment and other issues, allow to feed more complete analyzes.

From the data collected in the monitoring of initiatives and from a systemic vision, the analysis invites us to the implement a set of simultaneous actions to act in a comprehensive manner; likewise, corrective and preventive actions must be taken; working hand in hand with existing institutions and strengthening them; implementing leveling actions; and implementing strategies with objectives and actions in the short, medium- and long-term; Orienting the performance of employment centers and especially employers towards productivity and equity, and thereby qualifying the processes of human talent. structuring better mechanisms to allocate resources and promoting a much greater orientation in the initiatives towards measurement.

As explained, these learnings have allowed the structuring and updating of an inclusive employment model, which has been used both as a learning repository (bottom-up), and as a mechanism for accelerating results in the field (top-down). This has allowed the implementation of initiatives and concrete actions such as Social Impact Bonds, or the design and implementation of tools such as those described in the qualification of Schools and Employers.

There is still much to do to achieve the economic integration of the population that does not have access the labor market. In Corona Foundation we hope that the Model, and the concrete implementation of projects and tools, will allow us to move more effectively and quickly towards that purpose.

Footnotes

1 With more than 56 years of work in Colombia, the Corona Foundation has consolidated ample experience working to achieve social mobility, through the promotion of inclusive employment since 2013. In 2013, the foundation, aiming to contribute to achieving equity, quality of life, and development in Colombia, adopted a strategy to promote social mobility through two lines of action: Education to Employment and Education for Citizen Participation. The strategy was accompanied by a learning scheme, were monitoring and learning of local initiatives allowed the gathering of knowledge on how to address social problems through a systemic approach. For that, building scalable and replicable models became the core of the Foundation, and they are conceptual tools to assess the current conditions and needs of a territory and propose alternative solutions through the articulation of local actors, institutions, and even inform public policies. Throughout this paper we will share the learnings of these years. To learn more, go to www.fundacioncorona.org.

2 Estimated through analyzing information from EPBM (Preschool, Middle School, and High School Enrollment Rates) Statistics from the Ministry of Education, and the Enrollment Rate Statistics–EPBM also from the Ministry. Both data sets are available at datos.gov.com.

3 The Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje – SENA, is the National Training Service of the Government of Colombia.

4 El Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadísticas – DANE, is the National Administrative Department of Statistics of Colombia.

Author bios

Germán Barragán Agudelo is a political scientist from Universidad de los Andres, with a master’s degree on management and development from Universidad Externado de Colombia. He has published two articles and acted as Director of 16 publications related to inclusive employment. Currently, he serves as the Education and Employment Manager at Corona Foundation.

Daniela Matiz Bahamón has a degree in communications from the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. She is currently completing her master’s degree in business at the National University of Colombia. Daniela is a Communications Leader in Corona Foundation.

Works Cited

- CEPAL. División de Desarrollo Económico. (2012). Crecimiento, empleo y distribución de ingresos

- en América Latina. Santiago de Chile.

- CEPAL – OIT. (2017). Coyuntura Laboral en América Latina y el Caribe. Santiago de Chile.

- FILCO. (2018). Estadísticas de empleo: Ocupados.

- OCDE. (2016). PISA 2015 Resultados Clave. Recuperado de: www.oecd.org/pisa/

- Sánchez Torres, F., Munari, A., Velasco, T., Ayala, M.C. & Pulido, X. (2016). Beneficios

- Económicos y Laborales de La Educación Media y Acceso a la Educación Superior.

- Documentos de Trabajo No. 35. Recuperado

- de: dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2927158

- Sibs.CO (2019). MAPEO DE TIPOS DE RESULTADOS DE EMPLEABILIDAD Y EMPLEO INCLUSIVO EN EL PAÍS. BONOS DE IMPACTO SOCIAL. Bogotá.

- Fundación Corona, Enseña Por Colombia. (2019). Marco General de Orientación Socio Ocupacional. Recuperado de www.fundacioncorona.org.co/#/biblioteca/

- Fundación Corona, Fundación ANDI & ACDI/VOCA. (2017). Guía para la promoción del Empleo Inclusivo en la Empresa. Recuperado de www.fundacioncorona.org.co/#/biblioteca/

- Fundación Corona, Fundación ANDI & ACDI/VOCA. (2018). Promoción de Empleo Inclusivo desde la Cooperación Internacional. Recuperado de www.fundacioncorona.org.co/#/biblioteca/