Executive Summary

On January 7, 2008, in his inaugural address to the city of Philadelphia, Mayor Nutter pledged this: "To the law-abiding citizens of Philadelphia, I say we are the great majority. To the lawbreakers, you are in the small minority. This is our city and we're taking it back every day, every block, every neighborhood, everywhere in Philadelphia, because I've had enough and I'm not playing around about it," a bold but much-needed call to action in a city that at the time was looking at some of the highest crime statistics in decades and had been nicknamed 'Killadelphia'.

In 2006 and 2007, the city had seen its highest spike in murders, with murder rates resembling those of the early 90s. In addition, many of the city's neighborhoods were suffering from widespread quality of life issues and struggling to help themselves. Mayor Nutter followed up the bold statements from his inaugural address with immediate action that same afternoon, signing an Executive Order declaring a crime emergency in the city of Philadelphia. Newly appointed Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey and his staff had one month to submit a strategic plan for change.

Unfortunately, the mayor's term was about to coincide with the nation's biggest financial crisis since the Great Depression. The city was in store for several years of growing deficits, skyrocketing pension and benefits costs and major budget cuts, all of which would make any of the mayor's initiatives more than difficult to accomplish. However, despite the city's mounting fiscal and operational issues, this crisis would offer great opportunities to the mayor and his staff, specifically in the Managing Director's Office (MDO).

With the city asking every agency to do more with less, Deputy Mayor and Managing Director Rich Negrin, alongside his staff, would implement sweeping changes in the way the city was going to do business and address the city's growing list of issues. At the top of this list was crime and failing neighborhoods, and the solution was PhillyRising. PhillyRising is, on its surface, a traditional community policing model; but when itâs explored more deeply, it's a revolutionary and innovative way of structuring a program within a government hierarchy to circumvent bureaucracy and get things done. PhillyRising will show you how taking an old idea and simply reevaluating the way it's delivered can offer new solutions to one of the greatest problems plaguing cities.

The Problem: Crime and Disorder

In the months leading up to PhillyRising's conception, the MDO was seeking solutions to a number of problems they had identified as the sources of so many other problems within the city. The first, and most glaring, was the city's high crime rate over the previous several years. The second was neighborhoods suffering from extreme quality of life issues: vacant lots full of trash, parks serving as drug dens and littered with needles and streets pocked with holes. Finally, the third issue (which compounded the first two) was that individual neighborhoods didn't know how to solve the problems that plagued their communities and didn't know what resources the city offered to help them. All of these issues had a direct effect on city life, property values and business growth; a city in such turmoil was not a desirable location for a Democratic National Convention, a Super Bowl or the Olympics.

High Crime

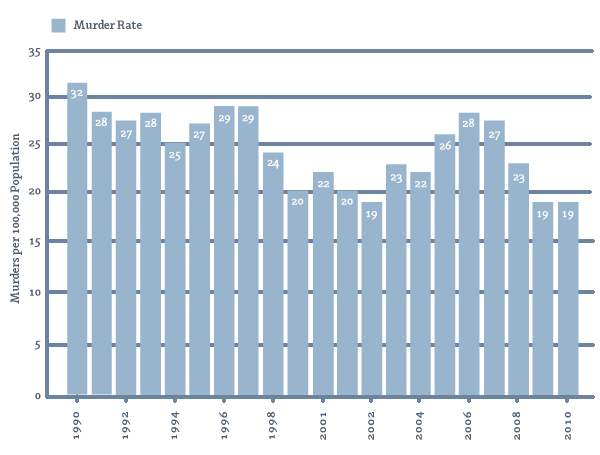

As noted earlier, on the day Mayor Nutter took office in 2008, he signed an Executive Order declaring a crime emergency and tasked newly appointed Philadelphia Police Department (PPD) Commissioner Charles Ramsey with developing a strategy to deal with the city's rampant crime problem. In the 2008 Crime Fighting Strategy that he presented to the Mayor, Commissioner Ramsey stated, "We can only fight crime once we understand it." This report would lay the foundation for much of Philadelphia's policing strategies in the years to come (Philadelphia Police Department, 2008). In 2006 and 2007, the city recorded 406 and 392 murders, respectively, a huge increase over the numbers in the early part of the decade that more closely resembled the murder rates of the early 90s. To put these numbers into better perspective, someone was murdered every 21.6 hours in 2006 and every 22.3 hours in 2007. At a murder a day, this gave the media-coined name 'Killadelphia' a ton of traction. Though the number of murders did begin to fall in the years that followed, as did the national numbers, Philadelphia was still the murder rate leader among cities of comparable size, experiencing a rate of 19.8 homicides per 100,000 people in 2010 (Philadelphia Police Department Research and Planning Unit, 2011).

Table 1: Philadelphia Murder Rates 1990-2010

Two other important statistics that PPD tracked were violent offenses and Part I Index crimes as defined under the UCR (Uniform Crime Reporting) Program. Violent offenses were murder, shootings, aggravated assaults and robberies, and Part I crimes were other homicides, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, theft and auto theft. Violent crimes posted some of the highest numbers for the decade, with 23,927 violent offenses committed in 2006 and 85,493 Part I crimes reported. Though these numbers fell slightly over the next three years, they still placed Philadelphia in the 10 most dangerous cities in America.

Quality of Life

Tied closely to the high crime numbers were quality of life issues. The city had neighborhoods plagued with widespread trash, graffiti, unsecured and collapsing vacant buildings, poorly maintained parks and open spaces and streets littered with potholes. On top of this. the street corners were home to prostitution and drug transactions. Once-beautiful playgrounds and parks were teeming with drug paraphernalia and needles; the "best" example was Kensington's McPherson Park, which was redubbed "Needle Park."

These issues also seemed to compound on each other: The unsecured, vacant structures became homes to vagrants and business offices for the drug dealers; unkempt vacant lots, with their overgrown grass and trees, became perfect covers for illegally dumping trash, tires and the occasional burnt-out cars; and the buildings that lined these poorly lit streets and alleyways became the targets of graffiti vandals. And all the while, the attitude that no one cared was being fostered within these neighborhoods.

Teaching a Man to Fish

Finally, the government was failing to address many of these issues primarily because community residents had no understanding of the city's available resources and services and thus they failed to report the issues appropriately. Most residents of neighborhoods outside of Center City had very little understanding of what the city government could do for them. They were used to paying their bills and taxes locally, or calling their local block captain with a complaint or concern. Residents never ventured to City Hall, let alone contacted them; the thought had just never crossed their minds. So quality of life issues continued to fester, growing and building on one another, ultimately compounding the crime problem and leading to the situation in 2010, when PhillyRising was still only an idea in the minds of Managing Director Rich Negrin's staff.

Broken Windows

Before we go any further, it is important to understand a very important concept here: the broken windows theory. Broken windows theory is a well-known, long-touted concept that links disorder and crime in communities. The simple premise is that if one building has a broken window that no one fixes, there will soon be more broken windows. Philip Zimbardo, a Stanford psychologist, best demonstrated this theory in a series of experiments involving leaving an automobile on the side of the street, one in the Bronx, New York, and one in Palo Alto, California. The automobile in the Bronx was left without license plates and with its hood up; the automobile in Palo Alto was locked and properly parked. In the Bronx, it only took 10 minutes for the first vandals to arrive, a family who scrapped the battery and radiator. Over the next 24 hours, the automobile was quickly stripped of anything of value, and then what remained was blatantly destroyed, leaving only a skeleton of a car; the automobile in Palo Alto sat untouched for more than a week. It wasn't until Zimbardo finally smashed part of the automobile with a sledgehammer that others decided to partake in the entertainment value of the destruction. Passersby each took turns swinging the hammer, and in 24 hours, the car had been flipped upside down and completely destroyed. What was the difference? Why the delay in behavior?

Broken windows theory says that the deviant and destructive behavior began sooner in the Bronx because abandoned vehicles and wanton destruction were not uncommon there. Automobiles were often left on the side of the road, property was scrapped and plundered regularly-this was the social norm in that neighborhood. This was not the case, however, in affluent Palo Alto; in this community, people valued their property, and thus, the social norms that were already in place there restrained the community from the same destructive behavior. It wasn't until these norms were challenged and the signal appeared to have been given that no one would care that seemingly law-abiding citizens began to take part in the destruction of the automobile. When the perception of value is dropped, and consequences forgotten, deviant behavior ensues.

Philadelphia's Story

Now comes the story of Philadelphia. Neighborhoods in the once booming city slowly began to crumble as post-WWII deindustrialization began to plague many cities throughout America. Factories closed down, properties went vacant, people began to care less and crime rose. Decades later, walking through some of these neighborhoods, it is difficult to tell which came first, high crime rates or the lowered quality of life, the proverbial chicken or the egg question.

When Philadelphia's MDO was tasked with determining the neighborhoods that most needed repair, staff utilized two pieces of data to qualify neighborhoods. The first was the PPD's crime statistics; the MDO focused on Part I crimes, identifying which neighborhoods had some of the highest violent crime rates. The second was the Streets Department's data on quality of life complaints like potholes, vacant lots, graffiti and garbage. When these data were overlapped, using PPD and Streets Department maps, the MDO was surprised to see the same neighborhoods having the same issues on both maps. This correlation identified the hot spots that would be the focus of PhillyRising moving forward.

The Solution: Community Policing

Community policing is a tactic that has been around for decades if not longer. As 1st Police District Captain Louis Campione explained, in his 37 years with the force, community policing had always been a part of the department, a key component instilled in young officers during their police academy training (L. Campione, personal communication, August 4, 2014). Community policing incorporates a number of tactics including foot and bike patrols, community outreach and community strengthening initiatives and careful coordination between law enforcement and civic organizations, among other components.

However, the most important aspect of community policing is that it includes communities themselves in identifying problems and brainstorming solutions to the issues that plague them. Community policing isn't just about fighting crime; it's more about disrupting the processes that lead to social disorder and crime.

Philadelphia implemented early community policing models in the 90s and saw some success, although there was always the question of whether or not crime had truly decreased or had just been temporarily displaced. As police presence and foot patrols shifted from neighborhood to neighborhood, so did crime, moving back and forth between. Two major police initiatives that saw local and temporary success were Operations Sunrise and Sunset. Under these programs, beefed-up police presence in high-crime neighborhoods quickly quelled visible crime, but only until funding dried up and PPD was forced to withdraw from those neighborhoods. Just as quickly as the crime vanished, it returned, resulting in wasted city dollars, time and resources. Thus, until 2010, Philadelphia was engaging in certain community policing tactics or components but falling short on the overall community policing strategy, largely owing to the lack of cooperation between different other city agencies.

Community policing requires not only engaging communities in identifying their problems and creating solutions but also that other city departments (e.g., Parks and Recreation, Licensing and Inspections, the Streets Department) all buy into the program and participate in the community policing efforts. However, what typically occurs is conflicting interests between departments that are all competing for a limited pool of city resources and funding. Put simply, each department submits a budget prior to the start of the next fiscal year, but that budget typically gets trimmed down (to varying degrees depending on the city) so that each department is then expected to accomplish its same goals with less. Now imagine that you're the head of the Parks and Recreation Department and a different city department asks for your assistance in one of that department's initiatives. This is initiative is possibly one of the reasons your department's budget was cut, so what's your incentive? What's your motivation to help a competing department deliver on one of its initiatives at your expense? The short answer is that there is no incentive or motivation. Thus, when PPD requested assistance from other city departments to address known quality of life issues that compounded neighborhood crime problems, they typically received little or no help.

Rethinking the Traditional Model

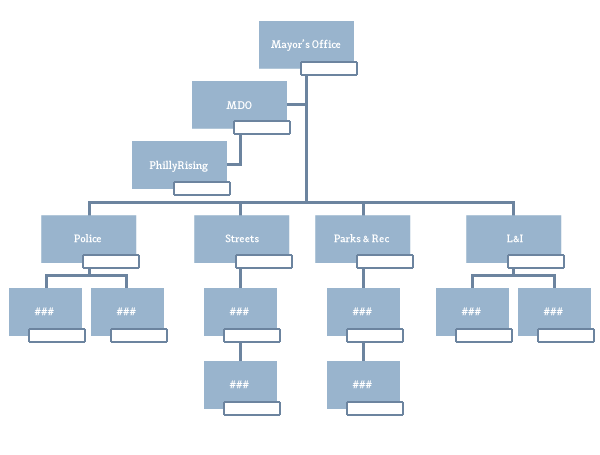

Therefore, what sets PhillyRising apart from conventional police department community policing models is that it is run out of the Managing Director's Office. The MDO oversees all city operations and departments, and by its operating PhillyRising out of an office that oversees all other departments whose components are required for successful community policing, there is seamless coordination between departments. Departments no longer choose whether to participate in PhillyRising because it's no longer just a PPD program: It's a city program. This simple adjustment in the organizational hierarchy guarantees cooperation among city departments.

Figure 1: The PhillyRising Community Policing Model

There is finally accountability, efficiency and coordinated efforts to address the key issues that plague the city. As Captain Campione explains: "The program succeeds where in the past other community policing models failed simply because the program is run from the city government on down to the operational departments versus being run from the police department on up. The Managing Director's Office is making other departments take ownership in the city's chronic crime problem and rising quality of life concerns and in doing so, brings together the best practices of every city agency and department" (L. Campione, personal communication, August 4, 2014). Now this doesn't mean that PPD isn't in charge of the community policing aspect of things; it just means that the other departments now also have a stake in the outcomes and participate when their services are needed.

The Components of PhillyRising

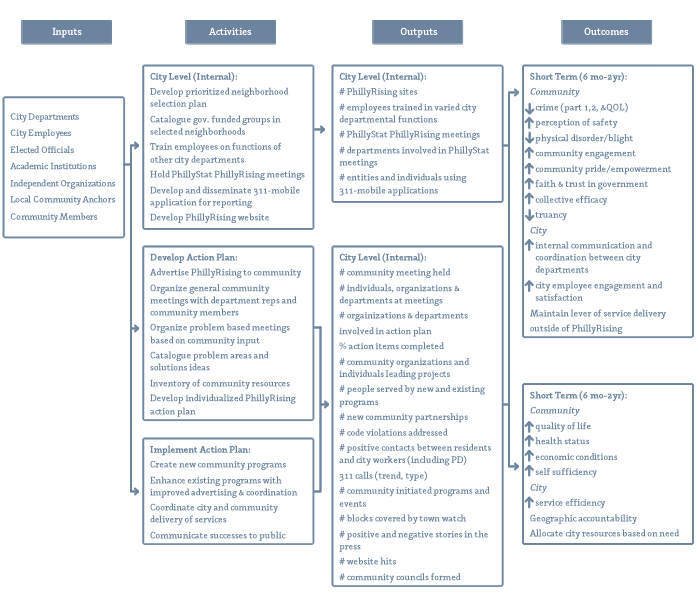

PhillyRising begins by first identifying the neighborhoods that most need help. As discussed earlier, this is done by carefully analyzing data provided by the Police and Streets Departments. Once the combined data are analyzed, overlapping trends in chronic violent crime and quality of life concerns identify the focus areas. Then PhillyRising sends a team into the neighborhoods to coordinate the efforts moving forward.

The first step is to organize a kickoff meeting that all community members, leaders and organizations are asked to attend where they're asked to voice their concerns. Though the initial tone of these meetings can be quite harsh, with residents wanting to focus more on blaming city government for its lack of attentiveness, the meetings quickly transition to constructive planning sessions; the community members explain their visions for their neighborhoods and then identify the obstacles that prevent them from reaching their goals. Once these goals and obstacles are identified, the community works closely with a PhillyRising coordinator to develop an action plan of the steps and tactics required to meet their visions and overcome their obstacles.

Once the plan is developed and agreed to by all parties involved, the implementation phase begins. Community events are organized to address everything from unkempt vacant lots, abandoned buildings to trashed and unsafe parks, public safety and so forth. These events include community clean-up and work days; building community gardens, parks or playgrounds; and increasing police patrols or specific crime targeting. As the action plan is implemented, the PhillyRising coordinator constantly monitors the progress on the plan and makes adjustments as necessary.

Citizen Engagement Academies and Philly311

PhillyRising also focuses on building long-term solutions to a community's quality of life issues. As Deputy Managing Director Adé Fuqua points out, the focus of PhillyRising isn't on solving all of a neighborhood's problems but on educating and engaging local residents in the process so they can learn how to identify and solve their own problems both today and in the future (A. Fuqua, personal communications, July 3 & 14, 2014). Three key components of this are Citizen Engagement Academies, myPhillyRising and Philly311.

The focus of each Citizen Engagement Academy is to educate community members on the city government's resources and how to access them. As was observed, many community issues have been exacerbated because no local residents knew where to go to address them. Each Academy is a free eight-week course designed to educate community leaders in the operations of local government; they learn about the tools they can utilize to strengthen their communities, and they learn ideas for bettering their neighborhoods. Course sessions include city departments and agencies discussing how community leaders can participate in code enforcement, public safety, sanitation issues and community building. The Academies also connect participants with other neighborhood leaders who face similar challenges, allowing for sharing ideas and experiences. Community residents leave the program with a better understanding of how to utilize the resources that city government provides as well as how to tackle many of the challenges they face within their neighborhoods.

The myPhillyRising website and app form a social media platform that allows stakeholders to collaborate and share ideas, organize events and publicize their successes. The website, which is designed primarily to be utilized on mobile devices, is similar to any other social media site, allowing users to create a login and profile, create events, RSVP to events, check in at events and post pictures and updates. The goal is mostly to simplify the process of getting involved in one's community (https://www.myphillyrising.com).

Philly311 is the city's customer service and information tool, providing citizens of Philadelphia with quick and easy access to government information and services. Rich Negrin explained it best in an interview with this statement: "You call nine-one-one for an emergency, and everything else is three-one-one." Philly311 covers everything from fielding frequently asked questions to directing complaints and calls for service to the appropriate department or agency. It operates as a physical call center, a website and a mobile app, serving as one more tool community residents can utilize to quickly access the city's resources, track the status of complaints and requests and receive information and answers to their questions.

Through Philly311 and the Citizens Engagement Academies, the MDO is not only solving the city's major issues but also empowering its residents by giving them the ability to take responsibility and help themselves.

People, Ideas, Hardware

A relatively unknown but influential Air Force colonel by the name of John Boyd once said, "People, ideas and hardware, in that order." This is important to note here because the success of PhillyRising, the thing that sets it apart from everything else, remains true to Colonel Boyd's principle: people, ideas, hardware. As was previously discussed, community policing is just another commonly utilized police strategy in the fight against crime. myPhillyRising and Philly311 are powerful examples of how technology can greatly enhance the capacity of a program or idea. However, these components of PhillyRising - the technology and the ideas - don't compare to the importance of the people who deliver the program and its services.

In part due to the opportunities created by the financial crisis of 2007-2008, Rich Negrin was able to assemble one of the strongest management teams in the nation. Once they were tasked with doing more with less, the old ideas, the old way of doing things had to be tossed out, and only a different mindset from a different group of people was going to accomplish this. It isn't unknown that city governments can be slow at getting things done; I don't believe anyone would ever characterize governments as fast. But Rich Negrin has been able to assemble a diverse team that speaks over five different languages, comes from countless different backgrounds and life experiences and has worked in the private sector, the military, nonprofits and government. This pooling of different individuals combined with the right management and leadership has created a team that has accomplished a lot with a little. Captain Campione champions the Managing Director's Office for their use of people: "The key is getting the right people involved and tapping into them. That is what the MDO is doing, bringing the best practices together" (L. Campione, personal communication, August 4, 2014).

What's important to take from this is that you can invest in the technology, the apps and the websites, and you can adopt the ideas, but if you don't have the people who want to do it and are willing to do it, you will most likely find yourself lost in the bureaucracy called government. Imagine the difficulty in trying to change the way things have been done for 20 years; it doesn't necessarily matter how great the idea is, and if you need proof, just remember that community policing isn't a new idea.

Social Impacts

The social impacts here are quite obvious. The city has successfully addressed the one major ill that has plagued it for years: crime. Crime overall is down throughout Philadelphia, and this is the overall measure that PhillyRising uses to measures its success. Neighborhoods like Hartranft saw a 21% violent crime drop and a 6% total crime reduction from 2007 to 2012. Point Breeze has seen a 35% violent crime and 18% total crime reduction, and the neighborhood of Eastwick has seen a 54% violent crime and 60% total crime reduction. Even more compelling than the numbers are the children playing on the newly constructed playground of McPherson Square Park. This park - the one once nicknamed Needle Park - was once home not to children playing but drug addicts shooting up; the needles on the parkâs field made the thought of a simple touch football game out of the question. Since PhillyRising's involvement in Kensington and the community-organized Kaboom Build event in 2012, McPherson Park is now home to a whole new crowd of playing children.

PhillyRising has also solved the issue of communities' failing to help themselves, with over 40% of PhillyRising neighborhoods' having achieved alumni status, which reflects that the community is able to organize, coordinate and run the PhillyRising program without the help of the PhillyRising staff. Alumni communities continue to get check-ins from time to time from the MDO, but for the most part, they have thorough knowledge of the city's departments and resources and can handle most issues on their own without direction.

Much of the program's success can also be seen in PhillyRising's operational budget. The budget has remained relatively unchanged since its inception, requiring roughly $670,000 of the MDO's budget, which mostly covers salaries. Beyond that, the program requires little else in the way of funding; it is essentially cost neutral. This makes sense in the sense that PhillyRising is really an existing idea that's just being more efficiently run by the MDO. If anything PhillyRising, might actually generate cost savings both internally and externally.

Regarding internal savings, tasks and operations are now being completed with more accountability, collaboration, and orchestration than ever before. This operational efficiency, combined with the long-term savings from the reduced stress on city resources stemming from high crime and poor quality of life, could mean long-term budget relief for a city that's already pinched.

External cost savings can also be seen in that PhillyRising helps to coordinate outside agencies and organizations that once duplicated efforts without regard for each other. In essence, nonprofit funding was being wasted because organizations refused to work together or had no way to coordinate their efforts. Now, PhillyRising serves as the conductor for these outside agencies and nonprofits, focusing on each organization's efforts to maximize the gains and benefits for its communities. Not only can city government do more with less now, but also so can nonprofits within the city, making for a powerful partnership.

What About the Long Term?

PhillyRising is clearly a success, and it has even earned a national award to prove it: the CISCO-sponsored IACP Community Policing Award for Community Oriented Government in 2012. The program is tackling three key issues that have plagued the city and compounded on each other for decades"chronic crime, quality of life concerns and communities" failure to understand and utilize city services. However, more can be done related primarily to how PhillyRising measures its success. Right now, it's focused on reducing crime and improving quality of life as well as measuring the number of murals painted, parks built, hours volunteered, trash cleaned up and so forth. But there are bigger measures that PhillyRising should begin exploring to help carry the model beyond the city to bigger possible stakeholders such state and federal policymakers, larger nonprofits and private businesses.

These measures include PhillyRising's effects on raising property values in its neighborhoods and shaping the return and growth of business within the city, another important initiative of this mayor and probably the next. The effects of crime and broken neighborhoods on property values and business growth in communities and in the city as a whole are evident. A method for tracking the changes in these two areas could definitely open the door to stronger support from the private sector as well as policymakers. With AxisPhilly no longer creating impressive visual model's of the city's data, a new partnership might be explored with one of the several major universities within the city; the University of Pennsylvania's Fels Consulting might be a start. Through this type of collaboration, scaling PhillyRising to smaller cities or even expanding its influence in state or national policies is more realistic for the future.

There is also some concern about where the program will be headed in years to come as the key people and players move on. As was already stated, the success of PhillyRising to date is largely due to the people who have been in place in the organizations involved, especially the Managing Director's Office. Fortunately, for PhillyRising, the programâs successes and its ability to successfully disrupt the cycle of crime and develop sustainable improvements to quality of life has influenced the thinking of the PPD 'the pillar of community policing' and other city department heads. This influence in city leadership's thinking is paramount for the program's continued success in the future. This kind of thinking can now be considered the norm, and its success, combined with little to no overhead, makes it a proven winner for any political administration looking to tackle one of any city's toughest problems.

Author Bio

Zachary Houck, MPA, is a recent graduate of the Fels Institute of Government and is a full-time career firefighter with the Cherry Hill Fire Department in Cherry Hill, New Jersey.

References

Mendte, L. (2010, July 15). Can Mayor Nutter keep his promise? Philadelphia Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.phillymag.com/news/2010/07/15/is-mayor-nutter-keeping-his-promise/

Philadelphia Police Department. (2008). Crime fighting strategy. Philadelphia, PA: C. H. Ramsey. Retrieved from http://www.phillypolice.com/assets/crime-maps-stats/ppd-cfs.pdf

Philadelphia Police Department Research and Planning Unit. (2011). Murder analysis Philadelphia Police Department 2007â2010. Retrieved from http://www.phillypolice.com/assets/crime-maps-stats/PPD.Homicide.Analysis.2007-2010.pdf

Kelling, G. L., & Wilson, J. Q. (1982, March 1). Broken windows: The police and neighborhood safety. Atlantic Monthly. Retrieved from http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1982/03/broken-windows/304465/