Introduction: PSIL Case Study

This case study of the Philadelphia Social Innovations Lab (PSIL) is the result of a semester-long graduate student research study of the inaugural Lab session. The researcher attended weekly Lab sessions and documented presentations, interactions and overall observations of how the Lab functioned. The case study provides perspective on how the PSIL has implemented objectives outlined in the syllabus, assesses how well it has succeeded in delivering on proposed outcomes and makes general predictions about its ability to deliver sustained and scalable social impact in the future.

PSIL Structure and Facilitation

The Lab is a mix of classroom, laboratory and accelerator structured among three core platforms. The initial phase provides participants with the opportunity to develop the basic competencies necessary for social innovation. The next step encourages participants to collaborate with each other and with experienced professionals while receiving expert consultations to support idea experimentation. The final segment ostensibly encourages continued testing, but is in actuality intended to accelerate the innovation toward investor presentations and project launch. Throughout the fifteen-week period the Lab very successfully adapted to the needs of participants. Instead of resolutely following a predetermined curriculum, the PSIL rapidly adjusted its outline based on ongoing feedback and periodic self-assessment surveys.

During the inaugural PSIL, each Lab session was split into two sections. The first half involved one or two external speakers who provided perspective on various aspects of entrepreneurship and/or social impact. These individuals came from a variety of backgrounds, working in the public, private and nonprofit sectors, or some combination of them all including the social enterprise sector. The diverse viewpoints gave participants sufficient opportunity to investigate various models and collaborate with individuals who have been successful in developing social innovations for a variety of societal challenges. The advisors offered expert ideas for designing business models, developing financial statements and building solid leadership teams. Each discussed social innovation within the context of their specific areas of expertise, demonstrating that innovation can occur in any sector, and often between sectors.

Lecturers would often remain after their presentations to interact directly with the innovators. In the first five weeks of the course meetings were less formal, giving groups of participants a more flexible opportunity to meet and consult with expert advisors, facilitators and other participants. In the latter part of the course participants had the opportunity to pitch their ideas to the experts sitting in as panelists after providing their own lectures. Participants had five minutes to present their ideas and receive immediate feedback. The commentary was extensive, honest and always constructive. Each week participants would pitch to new panels of experts, and learned to use the information gained from the previous panels to continually improve their pitch. Innovators not only received a sense of validation of personal efficacy, but also a sense of control over their learning environment (Bandura 1991, 270).

At the core of the Lab’s delivery strategy are three facilitators with strong backgrounds in social entrepreneurship, nonprofit management, executive leadership and academia. Each brings an extensive network of business associations that contribute expert consulting and networking opportunities for aspiring social entrepreneurs. Beyond their backgrounds, each brings his or her own unique approach to solving social problems. For example, Nick Torres tends to take a product- or service-centered approach to a new idea, while collaborating partner Tine Hansen-Turton thinks through the systemic and policy environments necessary to enable innovations to scale. Systems and design thinker Helene Furján provides a third dimension to developing innovative approaches to seemingly impervious problems. Each discusses their unique approach from the outset, informing the participants to expect any number of initial challenges while reminding them of the range of available approaches they might take to address them. The facilitators link people, ideas and investment potential to entrepreneurs, creators and designers in order to launch successful social innovations (Mulgan et al. 2007, 35).

Although the PSIL incorporates the foundational elements of most business acceleration services, it purposely generalizes them to avoid predetermining the legal status of a project. The innovation may generate profit, surplus revenue or a budgetary surplus, and operate in the private, nonprofit or public sectors. Innovations can grow into independent entities or projects within existing organizations. The core objective is to ensure that social innovations have the best opportunity to launch and deliver sustained impact. Cohorts of participants with untested innovations are the core audience of the Lab. Individual participants can also apply and participate, but are encouraged to identify partners to bring to the Lab sessions with them. This encouragement comes not only from Lab facilitators, but also from visiting consultants and expert lecturers with decades of experience in entrepreneurship.

The PSIL environment allows aspiring social innovators the freedom to test out new ideas, collaborate with fellow innovators and produce viable innovations that can address particular social needs. The Lab does this by establishing a platform of collaboration, where aspiring entrepreneurs can meet and explore social innovation concepts, exchange and debate ideas, and work together to generate solutions to social problems (Nambisan 2009). The unique nature of the PSIL lies in its ability to leverage diverse local networks while simultaneously providing classroom, laboratory and accelerator components to test, pilot and accelerate social innovations toward scale and replicability. The Philadelphia Social Innovations Lab is a full-service, collaborative environment taking innovations from idea to implementation, and innovators from curious to confident.

Defining Successful Outcomes

The PSIL course syllabus states that the goal of the Lab is to “increase the chances that the strongest ideas of social innovators will take root, attract the needed capital, and ultimately have a significant social impact regionally, nationally, and internationally.” The PSIL intends to deliver these outcomes by fine-tuning innovation through research and consultation, testing the innovation in the real world and seeding the innovation with interested investors. The syllabus also defines the key attributes of the Lab environment as: cross-sector, low-risk, high-return, data-rich and cooperative. The findings of this study are consistent with most of the intended outcomes stated in the syllabus. The PSIL enables participants to use best practices research and consulting to fine-tune innovations, pilot test models in both the laboratory and real-world environments and pitch their ideas to real investors. The Lab environment provides these cross-sector, low-risk and cooperative elements to the benefit of all participants.

The impact of and returns to participants (the ‘data-rich’ and ‘high-return’ attributes, respectively) can only be effectively evaluated after a period of time following the conclusion of the Lab. The participants’ final survey provided a preliminary assessment of the immediate returns to participants, but measuring true impact takes time. It will require calculation of the aggregate level of impact of all social innovations that graduate from the lab, while factoring in the appropriate attribution rate to the lab’s influence on the success of each innovation. A more subjective measurement will be the deadweight estimate, assessing whether or not the innovator would have succeeded without the support of the program (Evers and Silva 2012).

The PSIL intends to submit follow-up surveys every six months to validate the initial attributes and to provide a clear indication of how well the PSIL is tracking impact and individual returns. These will also serve as good indicators of attribution levels necessary to calculate the PSIL’s social return on investment (SROI). Estimating attribution levels based on the final course survey will provide data to estimate deadweight measures. As more data is collected, the results will demonstrate the long-term level of social impact each innovation, and collectively the PSIL, has at local, regional, national and international scale.

Types of Innovations

Inaugural PSIL participants brought innovations in education, community development, youth services, and micro- and small-enterprise development, with several that addressed multiple issue areas through integrated services. Many were looking to create independent organizations, while a few were interested in testing out innovations that could be implemented by existing enterprises, nonprofits or government agencies. The innovations ranged from the development of self-curated, online museum exhibit platforms for students, to the creation of an entrepreneurship incubator and light-manufacturing ecosystem for underserved neighborhoods. A few programs sought to integrate existing services such as mindfulness meditation instructor training for returning veterans, or combining youth bicycle maintenance training with urban farming programs to deliver locally-grown produce to lacking communities. Other projects leveraged technology and process innovations to disrupt the way current services are provided, including teacher coaching and the end-to-end public architecture design process. Some started as nascent concepts; others were already in pilot phases and ready to move to scale. The diversity of projects and development stages brought immense value to the Lab.

Lab students were furthermore encouraged to impart the knowledge they had gained while continuing to learn from their peers. This greatly enriched the peer-to-peer learning environment and allowed participants to adapt their projects, consider new ideas and even partner together on projects with similar objectives. Facilitators encouraged discussion and collaboration among different Lab participants, giving them control over the learning process (Ellerman 2004, 165), while creating an environment for social referential comparison to encourage goal setting and improve motivation (Bandura 1991, 254-255). Perhaps most important was how the facilitators skillfully encouraged this open learning environment while still ensuring participants had adequate access to information and networking resources.

The PSIL Platform of Collaboration

At the core of matching the ideas, innovators and delivery mechanisms is a strong platform where ideas can cross-pollinate to develop viable solutions. In order for such collaboration to occur, Satish Nambisan describes three primary platforms for developing social innovations: exploration platforms, experimentation platforms and execution platforms (Nambisan 2009, 46). As the names suggest, these service the public, private and nonprofit sectors as safe environments to explore, experiment and execute new ideas in the social innovation space. The PSIL attracts individuals and groups from diverse academic backgrounds, skill sets and interests and provides them the opportunity to collaborate and to work solo on separate ventures. This cross-sector cooperation is fundamental to the Lab.

Exploration: Establishing the Conceptual Base

In the first five weeks of the course, participants explore fundamental concepts in social innovation. Innovators use this conceptual knowledge to better define the issues at hand, their target populations, the resources necessary to implement solutions and the possible avenues to successful operation. The goal is to transform an idea into an innovation by taking a creative social sector solution and making it meaningful, in the form of goods or services, and preferably with some market value (De Miranda et al. 2009, 532). This transformation is facilitated through a Socratic learning environment. Participants are provided the tools necessary to comprehend key concepts, but expand their education by further investigating their own solutions, inquiring about various conceptual ideas and developing their own base of social innovations knowledge relevant to their project. The role of the facilitators is not to transmit codified knowledge, but to support the self-directed learning process (Ellerman 2004, 160).

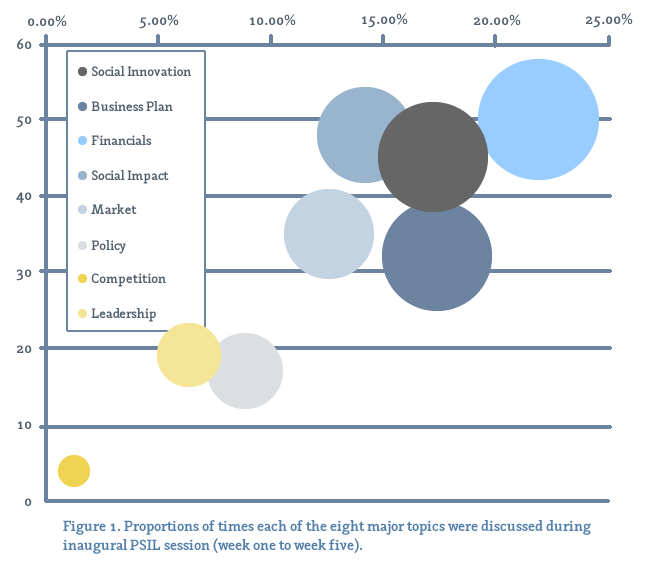

The basic tenets emphasized in the initial weeks of the course include social innovation, business plans, financial and social impact models, market and competitive analysis, policy/political analysis and leadership. These concepts have been identified as the fundamental components required to turn an innovative idea into a scalable solution. Based on notes taken during each Lab session, figure 1 shows the proportion each topic was discussed relative to the other key themes represented on the x axis. The y axis represents the number of times a key word related to that subject was used, and the size of the bubble indicates the total number of instances this topic was mentioned.

What is notable in figure 1 is the density of the core themes, which illustrates the depth of discussion between the Lab students and experts, and the overall inquisitiveness of participants (i.e., questions about various topics perpetuate further discussion, etc.). It is important to recognize the clear overlaps among these themes, when multiple topics were often discussed in conjunction with each other. Some examples include policy and political analysis, which ties into social impact strategy and social innovation on important levels. Competitive analysis is part of business planning, market analysis and many other essential components as well.

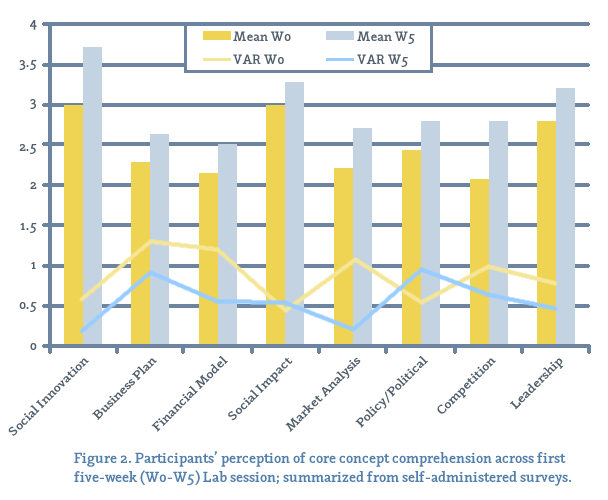

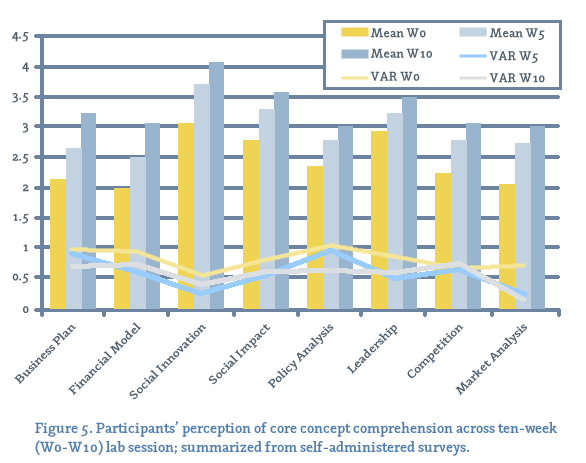

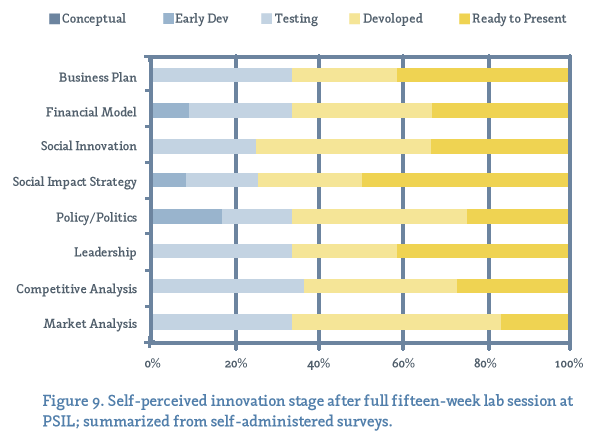

At the end of each five-week block, self-assessment surveys were administered. Along with monitoring overall progress, the surveys provided the participants with both the opportunity to monitor their own performance and an incentive to set goals, which according to Albert Bandura, can “enlist evaluative self-reactions that mobilize effort toward goal attainment” (Bandura 1991, 251). A review of survey results highlighted successes and shortcomings, and allowed the facilitators to adapt their approach to improve outcomes for the Lab in the future. The responses from the first survey (see figure 2) illustrate a mean increase in the self-perceived level of understanding of the core social innovations concepts from the point of entering the PSIL (W0) to completion of the first five weeks (W5).

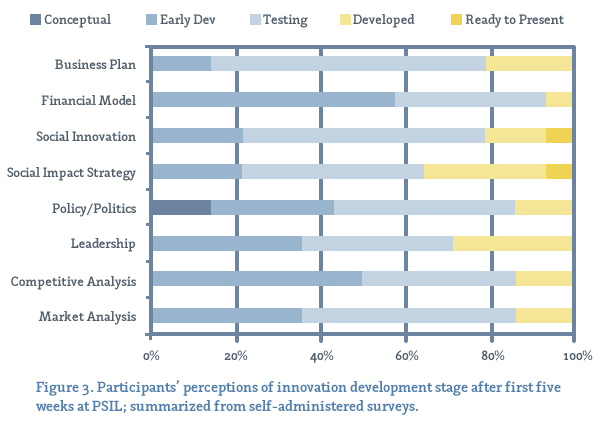

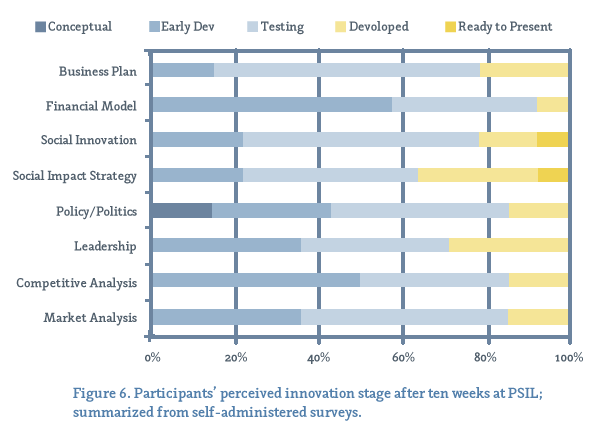

The decreasing variance in almost all concepts also demonstrates a convergence in understanding over the five-week period. Although there appears to be a loose correlation between the topics discussed (figure 1) and the perceived level of conceptual knowledge (figure 2), this is more illustrative than conclusive. In areas where the discussion level is high but the conceptual knowledge is low, participants tend to ask more questions on the topic, facilitating further discussion and increasing the overall proportional representation of a topic (figure 1). This graphic representation of notes fails to capture all one-on-one consultations with participants. Evidence of lower understanding is more apparent when we look at the gap evident in applying concepts to their actual innovations. After the first five weeks, most Lab participants still considered their innovations, as they correspond to the core competencies above, in the “Early Development” stage (figure 3).

Based on being “Ready for Testing,” the strongest component areas that emerged were Social Impact Strategy and Competitive Analysis. This is interesting because Competitive Analysis showed the lowest mean level of understanding in the core competency questions (figure 2) as well as the least-discussed (figure 1), while Financial Model had the lowest development stage (figure 3) and third-lowest core competency level (figure 2) despite being discussed the most frequently (figure 1). This indicates that Competitive Analysis was less understood and less- frequently discussed in the first five weeks, and as such not as highly prioritized by Lab participants. However, the topic of competition is more appropriately discussed in direct consultations, especially given the range of social issues the participants were seeking to address. Many sought to establish collaborative programs while others desired to break into entirely new segments. As we will see in the next section, the survey results provided the facilitators with better knowledge of how well participants were performing and subsequently, how well the Lab itself was doing. This feedback prompted adjustments to the subsequent sessions in order to more effectively meet both participant and Lab goals (Bandura 1991, 251).

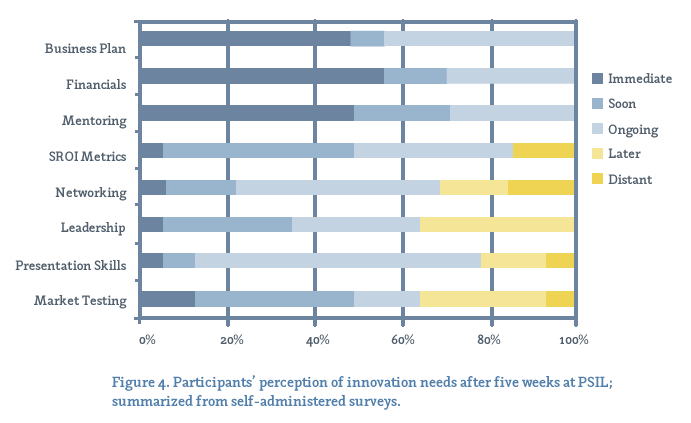

A third question set demonstrates the level of time sensitivity each participant experienced relative to different stages of their innovation (see figure 4).

These responses indicate that participants sought additional mentoring and consulting following the initial five-week block, primarily in the areas of Business Plan and Financial Model Development, which matches the density of thematic discussion on these topics (figure 1). These topics encompass many social innovation components. The relationships between the conceptual knowledge, innovation stage and time-sensitivity of needs allowed facilitators to recognize which areas needed additional attention in the next block of the course. In exploring social innovation concepts and the needs of their projects, participants developed a better understanding of these fundamentals through the lens of their innovation. The use of self-referential comparisons through surveys demonstrated the need to increase the application of this knowledge through experimentation. Upon completion of the first block, participants were ready to begin applying their newfound knowledge of social innovation.

Experimentation: Defining the Solution

“Experimentation platforms give organizations a neutral environment for building and testing solutions in stimulated or ‘near-real-world’ contexts” (Nambisan 2009, 48).

The experimentation platform is a vital strength of the PSIL. By the conclusion of the first five-week block, several participants had modified their innovations to more practical delivery models based on the conceptual knowledge gained in the first part of the course. Direct consultation with established social innovators, investors, foundations and academics also gave participants the opportunity to validate their ideas and gain critical feedback on how to improve their approaches. Outside of the Lab, participants were encouraged to test their market by interviewing potential customers, talking to potential funders and vetting their ideas with their potential target markets and ‘non-consumers.’ Identifying new customers and beneficiaries is a key strategy for successful business innovation (Christensen 1997), as well as for social innovation (Christensen et al. 2006; Lettice and Parekh 2010). This experimentation process allows participants to test the viability of their models both in and out of the Lab.

The immediate feedback inside the Lab often encouraged participants to go out and test their ideas directly with their expected customer base. One PSIL participant, Paul, created a self-curated online museum exhibit platform and proposed several different delivery models for presenting his concept. Paul was encouraged by Tine, Nick and Helene to speak with professors, teachers and administrators of university and K-12 schools to get a better gauge of the market demand for his product. By week ten, Paul presented to the class and listed numerous conversations he had held with a variety of different internal and external stakeholders. Most importantly this input gave Paul a clear path toward implementation. Another participant, Sam, tested his education technology product by not only pursuing a successful outreach strategy, but by also securing a live pilot test with a local charter school. Market testing an innovation ensures it has the attributes that its beneficiaries (or customers) demand. In several instances, participants found a strong interest in an idea, but often also identified slight product, service or delivery modifications that could make to a service or product to make it even more appealing. The exercise was encouragement to move forward with the next development step.

At the end of week ten (W10), another survey was conducted. This survey asked participants to reassess their level of understanding from when they first entered the PSIL (W0), through the end of week five (W5), and also requested them to gauge where they felt they stood educationally as of the end of week ten (W10). The mean understanding for each concept increased across the board over the ten-week period. This included Competitive Analysis and Financials, where Lab facilitators had incorporated the results from the previous surveys to increase access to resources on these core themes.

The variance (VAR) in figure 5 demonstrates a convergence in the level of understanding for most concepts, with the exceptions of Financial Model and Leadership, where a large convergence is observed between weeks one and five, followed by a divergence of the two between weeks five and ten. This survey was taken prior to a speaker on leadership in week 11, which likely explains some of the divergence for this particular topic. For the financial model, the responses indicate that some participants were still challenged in developing their financials (with over half still considering them to be in the “Early Development” stage).

Overall, the growth in understanding core concepts (figure 5) and mean increases in innovation development stages (figure 6) demonstrate the results of applying conceptual knowledge to innovations. The increase was supplemented by a positive shift in the innovation stage of most participants from “Early Development” to “Testing” (figure 6). In response to the first survey, facilitators adjusted parts of the Lab curriculum to address any gaps or weaknesses. This gave participants a better sense of control over their learning environments, which is important because “when people believe the environment is controllable on matters of import to them, they are motivated to exercise fully their personal efficacy, which enhances the likelihood of success” (Bandura 1991, 269). These self-apparent improvements are important indicators for how well the projects might progress. The increasing level of work undertaken outside of the Lab reinforces this notion.

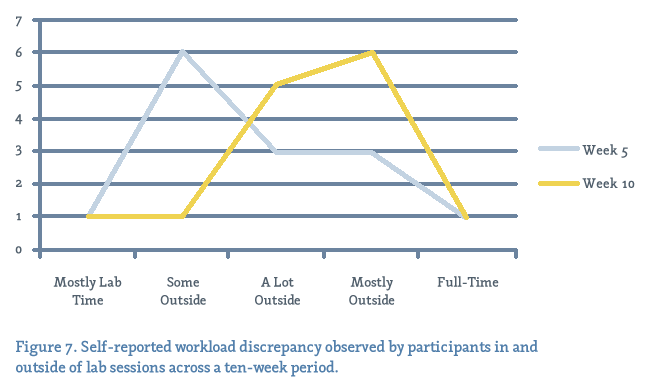

Figure 7 demonstrates a clear shift in self-reported workload, from half of the participants indicating that most of their measurable workload was accomplished within the Lab during the first five weeks, to (86%) reporting that the majority of their work was performed outside of the Lab. The summary of these survey results is an increased probability of successful outcomes for each of the Lab participants, and for the Lab itself. The form and level of this success is not yet clear, but the motivational elements demonstrate that all participants are likely to deliver impact at some level.

Experimentation is critical to social innovation, where few ideas emerge fully-formed and innovators often try things out and quickly adjust based on this experience (Mulgan 2006, 151). The cost of implementing a project prior to fully testing it can be enormous, especially if the results are negative or create unanticipated negative externalities. The PSIL offers innovators and organizations an adaptable and safe environment to experiment prior to implementation.

Execution: Presenting and Preparing for Launch

The execution phase begins with the final five-week block of the PSIL. Based on the syllabus, the output of the Lab is “to increase the chances that the strongest ideas of Social Innovators will take root, attract the needed capital, and ultimately have a significant social impact.” There are a number of situations where this particular Lab group might go on to launch their models, collaborate with others participants in launching an innovation or take part in scaling existing solutions. One benefit of having several projects in more advanced states earlier in the process in the lab is the social referential comparison (Bandura 1991, 254), providing strong motivation for fellow participants to accelerate their models toward execution. It is important to note that many presumed “failures” are vital and expected parts of the social innovation evolution. For instance, a curious social innovator might be absolutely confident that social entrepreneurship is simply not their intended path, perhaps decided after every idea he or she had generated was ultimately not put into motion. But they have still contributed to the field, as even failed ideas often point the way to ideas that will succeed (Mulgan 2006, 153). All of these outcomes should be considered as successes, as they help to direct human resources toward the right paths in the field of social innovation. Whether social entrepreneurs or social change agents within organizations, everyone can become equipped with the powerful tools they need to make a positive impact.

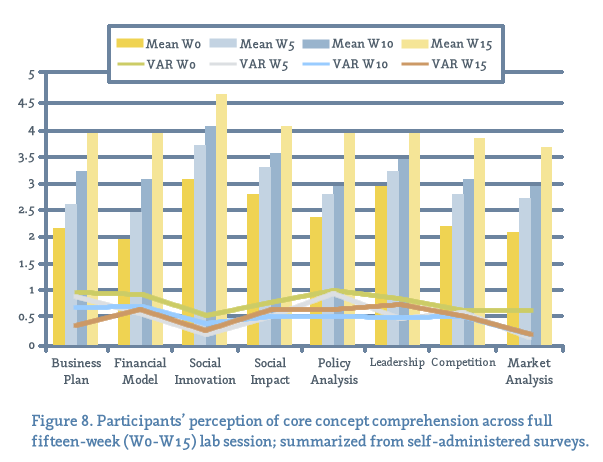

The final survey responses show signs of these scenarios. The overall increase in self-perceived understanding of social innovation knowledge, across all core concepts, was clearly demonstrated throughout the course of the PSIL.

The application of this knowledge has also grown, and the self-assessments of innovation stages reflect the continuing revisions as well.

These results show clear benefits of the Lab, but the question of whether or not the PSIL delivered on its proposed outcomes is incumbent upon the innovators themselves. In an effort to gain deeper insight into the networking benefits, participants were asked to “[p]lease talk about [their] experience[s] meeting and speaking with mentors, advisors or investors after the final pitch and/or outside of the class.” The responses contained a broad range of experiences and personal observations at PSIL.

“It was an amazing experience. I was incredibly grateful to have had the opportunity to get genuine feedback and from a group of highly experienced and knowledgeable professionals. It was truly memorable, exciting and very valuable.”

“Speaking after the final pitch was limiting. While a list had been sent out earlier, I didn't know who was who so I couldn't approach people as easily. I think the audience was skewed for interest in certain fields and mine was not one of them. I wasn't necessarily expecting an investment, but had thought there'd be more feedback and/or questions from others.”

“No one would speak to me.”

“Immediately after the break, I had one of the guests approach me with wonderful, energetic feedback and the intention to meet for lunch to discuss it further as a mentor or advisor. We are setting up a meeting for the end of this week. One or two other conversations helped to pinpoint potential clients for us in the future as well as other potential collaborators.”

“We are meeting with a potential investor this week that was [present] at the final pitch.”

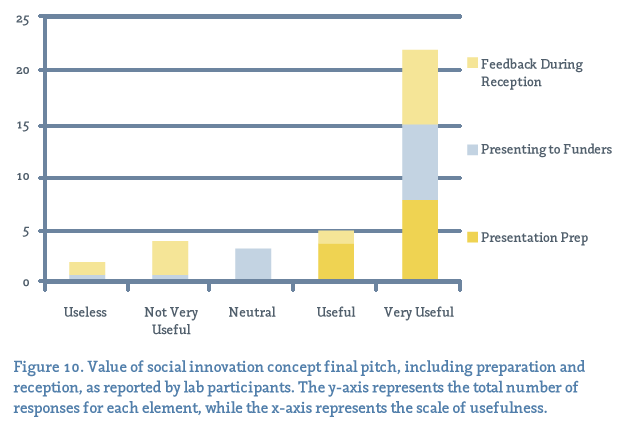

Despite the variation in comments, it appears that most participants found the final pitch and reception feedback quite useful (figure 10).

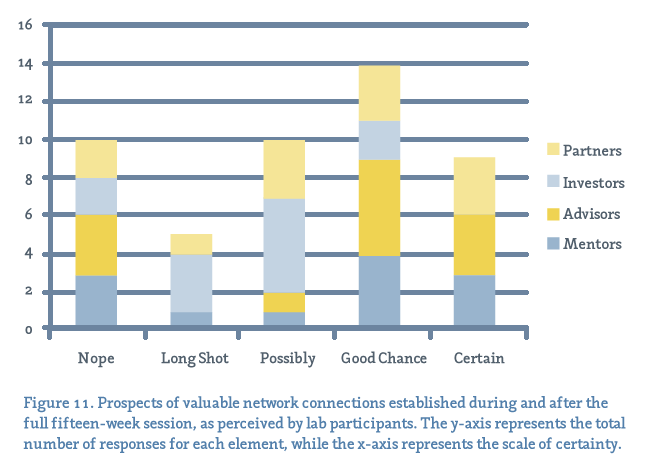

There is also an array of perspectives regarding the benefits of networking, and this was evident in the assessment of networks established during or after the fifteen-week session at PSIL. Participants appeared to have either a very positive or quite negative networking experience, although in general the impressions were positive.

Based on these responses and the commentary above, it appears that the variance could be a result of the sector in which the potential investors and advisors work, or at least those attending the final pitch. There are mixed results regarding the network connections established throughout the Lab. The majority of participants had high confidence in securing mentors or advisors through the PSIL, but felt much lower confidence in securing investors. Although some projects indicated they were not seeking funds at this time, these responses have a few possible explanations. It could be that some participants were simply not successful networkers or are not as entrepreneurially-inclined. This could be remedied through a more selective admissions process, or by providing more information about effective networking. Another explanation is that participants did not adequately tailor their presentation to the investors attending the pitch. Additional support in matching innovations to potential investors could help address this in future Lab sessions.

Although facilitators make every effort for participants to succeed, the outcome of the individual or cohort’s innovations is entirely up to the innovator. The Lab serves as a source of knowledge, feedback, networking and general resources, but the level of achievement ultimately depends on participant’s level of effort. This includes the drive and ability to establish and strengthen network linkages when resources are available. In some cases, participants will realize that entrepreneurship is just not their path. Or, they may accept negative experiences as part of the challenge of entrepreneurship. One participant responded to the survey by saying that, “none of the attendees of the final pitch showed interest in my project, which should probably tell me something, but I'll ignore it for now.” The idea of ‘ignoring’ a perceived lack of interest is fundamental to the social entrepreneur and the relentless pursuit of their visions (Bornstein 2007). A large part of the individual project’s success depends on the drive of the individual behind the idea. Motivational tools are provided throughout the Lab to drive toward successful launch, but the Lab itself is intended as a low-risk environment for aspiring innovators to explore and experiment with potential social innovations. Ultimately, it is the innovator that must execute.

PSIL Outcomes: Different Forms of Success

Based on the observations and assessment of this case study, there are four possible outcomes for PSIL participants. All accelerators share the goal of launching successful projects, but the three alternative outcomes make the PSIL a unique environment for risk mitigation. It also increases the likelihood of successful innovations reaching scale.

Success as Innovation Launch

The core objective of the PSIL is to launch successful innovations capable of scale. But the facilitators do not force any idea through the lab and into the community. Instead, the PSIL allows participants to truly test out ideas in an open and collaborative environment, building core skills while also receiving honest feedback and allowing for innovators to adapt or change their model to increase the likelihood of success.

Success as Failure to Launch

This seems counterintuitive until you consider the laboratory component of the PSIL. Labs are intended to allow for testing and failure, while mitigating the negative impact of failure. In this environment participants have reduced personal, professional, organizational and financial risk, and thus society is protected from ideas that cause unintended damage. As mentioned earlier, the failure of an idea is not always the end of an innovation; rather it allows the participant to redirect energies to projects with similar objectives (Mulgan 2006, 153).

Success as Collaboration

PSIL applicants are expected to bring an innovative idea to the Lab, but it is entirely possible that two participants will have very similar objectives. Participants are repeatedly encouraged to partner either within the Lab or identify outside partners in order to increase their chances of success. In response to the final survey, one participant commented that by “Observing the other participants, the value of having a full-time partner for this type of project became very obvious.” Several participants identified similar goals and decided to partner on projects. Collaboration can also occur between two different projects to ensure mutually beneficial outcomes. In the inaugural PSIL session, one participant’s first customer was another project in the Lab. Another participant collaborated with a facilitator to implement a live test environment. Two other participants collaborated on an innovation that had already launched, leading to a fourth successful outcome.

Success as Resource Matching

A major strength of the PSIL is the network of its facilitators, advisors and sponsors. It also attracts highly-talented and motivated individuals seeking to have positive social impact. But if an innovation is not ready to launch, and no projects within the lab are of interest, there are a number of external projects seeking talented and motivated individuals to help take projects to scale. Another way to view this outcome is the PSIL as a social innovation venture Lab. The PSIL brings together a variety of resources and testing ideas, ultimately generating change by growing and diffusing social ventures (Shanmugalingam et al. 2010, 23). In attracting social innovators with audacious ideas, there will inevitably be participants that realize their ideas are not feasible at the present time. The PSIL provides them an opportunity to contribute to innovations with existing resources and already in the execution phase. Responding to “one of the barriers to scaling effective social innovations [being] the difficulty of attracting and retaining sufficient affordable and skilled talent” (Dees 2012, 325), the Lab provides the unique ability to match the appropriate talent with financially sustainable projects. This is a unique feature of the PSIL that provides a mixture of Social Innovation R&D and Social Innovator Talent Acquisition, testing scalable solutions with the support of ambitious and skilled individuals.

The PSIL will produce each of these outcomes, meaning the benefits of the Lab may vary by the participant. For instance, Sam Edwards entered PSIL with a strong innovation and had already completed significant work toward launching his social enterprise. This included previously attending another incubator and applying to numerous fellowships and innovation awards. He also demonstrated clear entrepreneurial skills and the necessary drive for launching the project. The benefits of the Lab for him came primarily in pitching the idea numerous times to a variety of potential investors, as well as building a more robust SROI and Financial Model. Sam exemplifies a successful launch outcome.

Other participants entered the Lab with sound ideas and execution plans, but through the course of Lab sessions ultimately decided to partner with other participants. Others changed their approach by seeking to leverage existing organizations instead of launching an independent entity. This was clearly an outgrowth of the Lab, after several speakers discussed the need to recognize the existing ecosystem of programs before creating another organization to compete for the same limited resources. Two other participants entered the Lab with vastly different ideas but ultimately abandoned those concepts because of their own time constraints, coming together to work on another innovation with high potential. This last instance was an unforeseen outcome of the Lab, but one that is clearly positive. Instead of discouraging participants from pursuing goals of social innovation, the lab identified project managers for an innovation that was ready to scale.

The adaptive nature of the lab increases the potential for success. Establishing predefined outcomes limits the ability of the participants to maximize their potential for positive social impact. The PSIL environment allowed each participant to approach ideas based on their perceptions about the world as they see it, providing the intrinsic quality and essence of their motivation (De Miranda et al. 2009, 529). The adaptability allowed participants to modify their approaches to more successful outcomes, or postpone their ideas and take the opportunity to gain experience executing a more-developed concept. Motivated individuals with overly-ambitious ideas are not discouraged, but provided the opportunity to participate on successful projects.

In this instance the PSIL also works as an R&D Lab for ideas as well as individuals. It attracts bold ideas and ambitious people. The PSIL helps converge innovative thinking and social ambition to scalable solutions that can address social problems by serving underdeveloped markets (Fabricant 2013). It does so by not only cultivating existing innovations, but by enabling motivated change agents to pursue social impact opportunities. One can imagine the number of talented individuals that stop pursuing their ambitions for social change and settle for more conventional career alternatives. Here, the PSIL diverts from this traditional path. It offers ambitious individuals the opportunity to pursue a social innovation crafted by experienced social entrepreneurs, implemented through their existing networks, and able to demonstrate the potential of scalable social models.

Conclusion: PSIL as Social Innovation

“Partners use the exploration platforms to define what the problem is; they use experimentation platforms to test possible solutions to the problem; and they use execution platforms to disseminate the solutions” (Nambisan 2009, 46).

At the start of the Lab course there were 16 independent projects, many with overlapping objectives. While some participants walked in seeking to refine their innovations for funding pitches, others simply had an idea to address a specific social problem. The exploration platform provided the opportunity to learn from experts in a variety of fields, pose questions, engage in dialogue and learn from different approaches. The PSIL served as a “people, network and expertise intermediary” organization by building the skills, bringing in the expertise, and offering training and matching new partners for developing innovations (Schanmugalingan et al. 2010, 21). The diversity of backgrounds and concepts provided innovators with valuable opportunities to learn from both facilitators and their fellow Lab participants.

By the end of the first five-week block, this number had condensed to 11 projects with several individuals combining ideas. Some of these combinations occurred as a result of obvious synergies, but others changed course for another very important reason. The Lab provides the opportunity for individuals to fully experiment with ideas, even if they turn out to not be viable for any number of reasons. The ultimate goal is not to force the original idea to work; it is to ensure motivated social innovators have the opportunity to implement working solutions. Organizational forms ranged from independent organizations to programs within existing institutions to programs operating between sectors. Many of these changes came from testing ideas both within and outside of the Lab. The level of collaboration between projects was high, shown by participants reacting to opening presentations, meeting during and after the lab session to offer suggestions and network connections, and supporting each other through the final pitches. The cross-fertilization that occurred between these innovators was extremely valuable to developing more comprehensive solutions.

The execution phase has just begun for the current Lab participants. Final pitches were delivered on April 23, 2013, and the final survey submitted three days later. These surveys measured final self-assessments as well as captured data on networking connections established and future plans to continue projects. It is evident that several participants will continue to pursue successful projects, while others may ultimately pursue a different career path altogether. Follow-up surveys will be used to collect information on impact, and provide critical deadweight and attribution measures to determine the overall SROI for the PSIL. As additional cohorts move through the PSIL program, the level of data will increase along with the scale of impact. In many ways the PSIL will serve as a magnifier of impact, helping connect motivated and talented social innovators to the political, social and financial capital needed to nurture innovations from impact to scale.

When innovations have successfully launched and moved to scale, the dissemination of knowledge will be handed off from the PSIL to the The Philadelphia Social Innovations Journal (PSIJ). The PSIJ serves as the execution platform for scalable and replicable models. The most viable solutions developed in the PSIL will eventually be featured in the PSIJ, and the ideas will then spread to a broader community. This is critical to the sector as a whole because “[a]dopting new solutions often creates ripple effects within and outside organizations. And so the final task for execution platforms is to help their members manage these system-wide changes” (Nambisan 2009, 49). The PSIL-PSIJ relationship is developing an ecosystem where social innovations can go from idea to implementation, from implementation to scale and from scale to shaping policy. An important next-step in furthering this ecosystem is more formal collaboration between the various social impact initiatives within the University of Pennsylvania, and the development of a center focused on social innovation to bridge these various initiatives (Liberati and Furján, 2012). Around the globe, “[u]niversities have a special role to play in this new economy as institutions which form ‘new citizens’ and new entrepreneurs, and make their R&D facilities greater ‘solvers’ for local realities and problems, as well as cultural needs and services,” (De Miranda et al. 2009, 534). The need for social innovation extends beyond business, social policy, design or other distinct disciplinary approaches (Nicholls 2008, xiv). Blended value requires blended methods. The PSIJ collaboration with the Fels Institute of Government and PennDesign that created the PSIL is a solid foundation for the University of Pennsylvania to help lead this new economy. Continuing to focus the energies of the various schools and departments into a concentrated effort would be a true social innovation.