Summary

Food insecurity is the inability to afford enough food to maintain a healthy and fulfilling life. Since the 1960s, the U.S. has seen food insecurity increase drastically from one in 20 Americans to now one in seven. In Philadelphia, the situation is worse where one in four experiences food insecurity. In an effort to help move the needle forward, Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha’s (APM) Food Buying Club (FBC) devised a viable system to deliver quality fresh produce to residents while addressing the driving factors of household economics and neighborhood environment. The FBC model addresses food access as both a condition of societal determinants of health and a distribution management problem.

Food insecurity is the inability to afford enough food to maintain a healthy and fulfilling life. Since the 1960s, the U.S. has seen food insecurity increase drastically from one in 20 Americans to now one in seven. In Philadelphia, the situation is worse where one in four experiences food insecurity. These numbers have continued to rise despite investments to improve health and increase access to healthy food, and proximity to the largest temperature-controlled public wholesale produce market in the world. In an effort to help move the needle forward, Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha’s (APM) Food Buying Club (FBC) devised a viable system to deliver quality fresh produce to residents while addressing the driving factors of household economics and neighborhood environment. The FBC model addresses food access as both a condition of societal determinants of health and a distribution management problem.

Food Insecurity in Philadelphia

The availability and affordability of nutritious foods is a major health concern in all communities. Food, the most basic human need, affects every aspect of a person’s life including physical and mental health. While the relationship between income and poor health is well-established,1 the correlation between food insecurity and quality of life is confirmed in the case of Philadelphia.

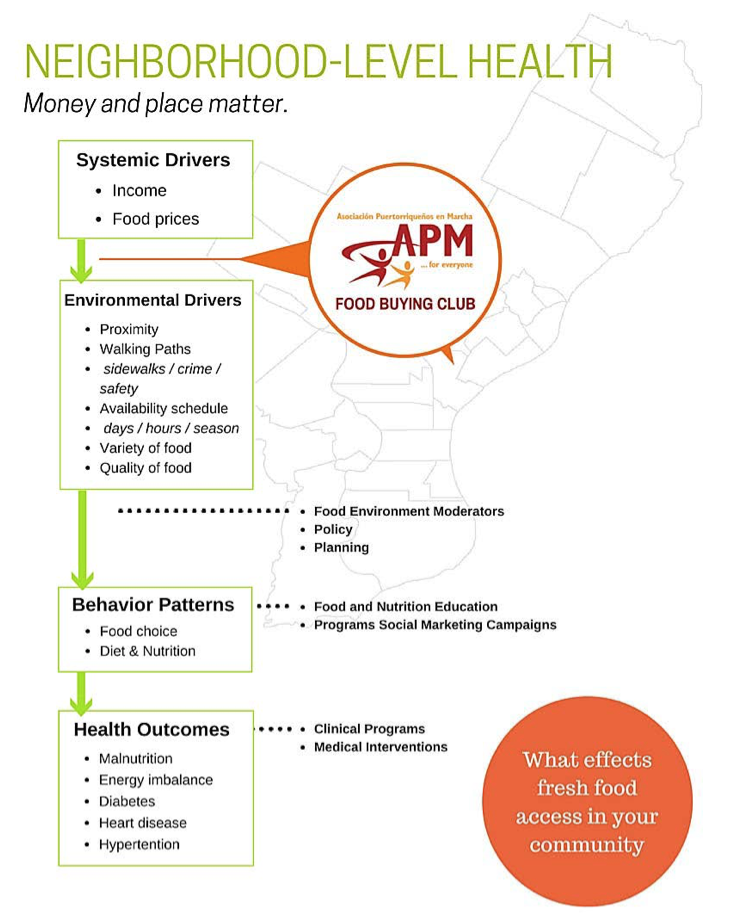

For food choices and health outcomes, money3 and place matter. Philadelphia, like most U.S. cities, is changing. While some neighborhoods (4 percent) are gentrifying, nearly half of Philadelphia (44 percent) is experiencing the opposite effects of economic decline and concentrated poverty.2 These areas are seeing significant drops in median household income, which in turn has increased the number of residents living in poverty by 60,000. Due to inactivity and unsold inventory, some grocery stores and farmers markets closed.

In line with declining incomes, poverty and deep poverty in the city remain high.4 More than one-quarter (28 percent) of residents live in poverty. Among the ten largest cities in the U.S., Philadelphia maintains the highest deep poverty rate at 12 percent. These families make less than half poverty-level income; for a family of four that can be as low as $11,700/year. Corresponding to concentrated poverty, entire neighborhoods in Philadelphia deal with pervasive poor health outcomes.

Philadelphia also maintains the highest rate for obesity and health-related chronic diseases.5 Type 2 diabetes, heart disease and stroke are burdens particularly for low-income and non-white residents. Following the declining income trend, from 2003-2014 the number of people in Philadelphia relying on pantries grew four-fold (from 130,631 to 572,006, respectively).5,6 In 2014-2015 alone, requests for emergency food assistance rose 7 percent, 10 percent of which went unmet, and expanded to include people who were employed. Additionally, the number of people living in areas with low-to-no walkable access to healthy food increased 11.2 percent.7

In June 2014, APM FBC administered a baseline survey to residents in Eastern North Philadelphia. The goal was to understand how families spend time and money on food, specifically fresh produce. The results offer a clear view of how economic and neighborhood-level issues shape food-buying habits. Respondents reported less income than both the U.S. and Philadelphia average; the majority fall well below the poverty line. The U.S. Census Bureau estimated the poverty threshold for a family of three in 2015 was $20,090. APM respondents earned less than $5,000 to $15,000 annually.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), a family of four with small children must spend approximately $840 per month to attain a “low-cost” diet plan goals in our mainstream retail market. That is $7 a day for each person. 8Data collected over a year showed that families in APM’s area have only $168 or less per month to spend on food. This information supports feedback about families living on fixed or limited incomes, check-to-check and reliance on subsidized benefits to make regular food purchases.

Adding to economic challenges of food access, residents in APM’s area also face environmental barriers. These include but are not limited to: physical conditions; crime and safety along walking paths; proximity; schedules and availability; quality and variety of food choices. The following socioeconomic and environmental challenges exist:

Crime: Crimei average (21.6 percent) is 2X that of the City of Philadelphia

Economic: 32 percent of African American and 42 percent of Latino residents live in poverty compared to national percentage of 7.4 percent; unemployment rate is 26 percent, 3X the City’s rate of 8.9 percent; the median income hovers around $15,540

Food/Health: 40 percent of North Philadelphia residents are eligible for food stamps; 44 percent suffer from hypertension; 33 percent suffer from obesity; 18 percent from diabetes.

These disparities remain despite implementation of a variety of strategies to increase access to affordable, nutritious foods in low-income neighborhoods. In 2010, for example, through the support of the national Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Prevention and Public Health Fund (PPHF), Philadelphia was able to increase funding to programs for prevention and public health programming. The mission: to “protect and promote the health of all Philadelphians and to provide a safety net for the most vulnerable.”9 In a move to increase health through the consumption of fresh produce, the PDPH formed partnerships to increase awareness of diet and nutrition, allow for subsidized purchase of fruits and vegetables from local farmers markets and increase supply of fresh produce for purchase at corner stores.

Despite renewed efforts, Philadelphia still saw an increase in the number of people living food insecure and in poor health. These increases suggest a problem-response mismatch6 between policy and program design. For instance, local data suggest 70 percent of residents would eat more fruits and vegetables if they were fresh, affordable and available in their neighborhood. However, programming models funded through Philadelphia’s health improvement plan have been largely aimed at research, increasing access to information and delivering education programming. Attention was allocated to issues simply correlated to health outcomes and people’s behavior patterns while considerations for socioeconomic causes and local environment become a lesser, even competing priority. As a result, programming for nutrition and health education about what people should eat increased while cash flow and physical access to healthy food for low-income families did not.

The FBC Model

Household economics and limited buying power have made quality fresh produce a luxury item for families in Philadelphia. APM FBC’s approach to food access differs from existing program models because it keeps the primary focus of providing a financial benefit to members. The APM FBC works by allowing residents (the end consumers) to skip ahead in line in the regional food distribution channel and access fresh produce at its peak freshness and lowest price point, up to 1/3 of retail cost.

Typical food-buying clubs are small groups of people who get together to buy food in bulk directly from a distributor or wholesale market. Through the FBC, residents buy food in bulk from the Philadelphia Wholesale Produce Market (PWPM). Over time, members of the group or Club save money over regular retail prices while gaining access to food they want to eat and connecting with other people in their community. Time and money are saved and households can put that free time and savings toward other needs. This is where similarities end.

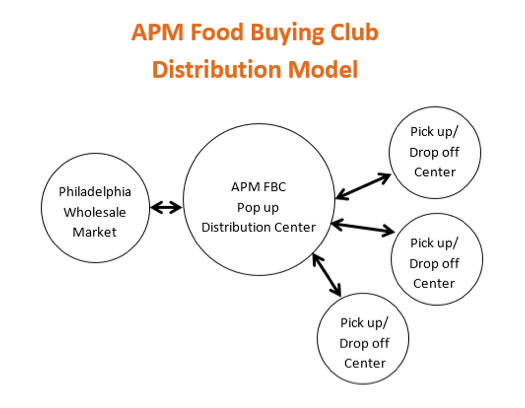

Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha’s (APM) Food Buying Club (FBC) model is unique in its flexibility to adapt to the needs of different communities; it has potential for growth in scope and scale. Through the FBC, APM is able to offer more families access to higher quality fresh produce at affordable prices (60-75 percent off retail cost) without forgoing their power of choice and building community. Utilizing the logistical hub and spoke model employed by FedEx, APM acts as the supporting hub (pop-up distribution center) for the FBC where complicated operations such as accounting and sorting are processed. The spokes are familiar community locations where residents place and pick up their orders. Free time and savings gained through the FBC can be put toward other needs.

Dropping income requirements, proof of residency and membership fees allows for a diverse customer base, which provides financial sustainability for the FBC Hub. As purchases from higher-paying customers provide revenue to offset supply and cost fluctuations at the market, lower-paying customers benefit from consistent savings and availability. In addition to helping families stretch their buying power for groceries, the FBC works closely with APM’s Financial Opportunity Center (FOC) to assist families in securing more income through connections to job training, employment support and benefits counseling.

The strategic placement of pick-up sites allows members access to healthier food within settings they are familiar with and trust. Designed as a replicable, community-based model, APM’s FBC is influenced by community and economic development concepts that include community engagement and environmental design such as Tactical Urbanism and Creative Place Making. The market predevelopment process is guided by principles of grassroots organizing, 2nd-Generation Crime Prevention through Environmental Design (CPTED), and Human Centered Design. The community engagement component adds to the FBC’s iterative development process. Working with residents, the FBC addresses community-level conditions—social determinants of health—that limit access to quality, affordable and healthy food. Starting with the target consumers and their stated needs is necessary work for sustained program interest, improved community capacity and connectivity through food access.

The Advantage

In its pilot year, APM FBC recorded the average food order at $24. That translates to an average of 35 pounds—approximately a case—of fresh, quality, nutrient-dense produce. In a retail supermarket the same order would cost $75. Through the APM FBC residents are able to buy three times more produce than they would be able to afford from a retail grocery store. In the first 47 weeks, APM's FBC served over 600 households (about 1,400 people), saving members cumulatively over $121,000. Through two hubs, the FBC distributed over 62,000 lbs. of fresh produce through six spoke/satellite pick-up sites, employing five residents in a part-time capacity.

To sustain the FBC model, Asociación Puertorriqueños en Marcha leveraged a track record and established role as a catalytic backbone agency serving the Greater Philadelphia community. The Food Buying Club is part of a long-term neighborhood Community Economic Development (CED) strategy. To achieve consensus on a shared vision and strategy for food access in their area, APM worked to identify and give voice to quality of life issues by hosting regular community meetings and conducting monthly community outreach though the Community Connectors Program. APM continues to act as a convener of community residents and other organizations dealing with the critical issues their constituents face, such as food hardship, housing development, financial literacy, blight and crime.

To support the Food Buying Club as a CED program, APM mobilized resources in the form of in-kind donations and grants. Philadelphia Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) and Bank of America provided financial support for the administration needs of the Food Buying Club. U-Haul International supports the Food Buying Club through in-kind donation of vehicles for transport of produce for distribution.

Through research and experience, we are beginning to realize that income and place matter for health outcomes. Existing nutrition incentive programs have failed to address unequal access to good, fresh, affordable healthy food where food decisions and diet quality continue to be shaped by local socioeconomic and environmental factors. In order to make immediate impact and lasting change, policy and programming need to pivot to address food access as a local socioeconomic and environmental condition requiring market-based solutions and logistical delivery management.

The FBC is currently completing a sharable ordering and distribution management database and training manual to further increase the ease of FBC start-up and operations. The immediate aim is to establish at least one new hub (pop-up distribution center) and three new spokes (pop-up pick-up/ordering sites) in the next year. With growing, continued financial support from public and private partners, over three years the Food Buying Club expects to expand its reach to other areas of Philadelphia County experiencing food hardship.

References

1. John W. Lynch, George A. Kaplan, and Sarah J. Shema, "Cumulative Impact of Sustained Economic Hardship on Physical, Cognitive, Psychological, and Social Functioning." The New England Journal of Medicine 337, no. 26 (1997): 1889-1895.

2. Emily Dowdall, Philadelphia's Changing Neighborhoods: Gentrification and other shifts since 2000. Philadelphia and Washington D.C.: The Pew Charitable Trusts (2016).

3. Greg J. Duncan, "Income Dynamics and Health." International Journal of Health Services 26, no. 3 (1996): 419-444.

4. “Our Plan to Fight Poverty: The Crisis,” City of Philadelphia Office of Community Empowerment and Opportunity, Shared Prosperity Philadelphia, accessed October 16, 2016, http://sharedprosperityphila.org/crisis-level/.

5. “Walkable Access to Healthy Food in Philadelphia, 2012-2014,” Philadelphia Department of Public Health (PDPH), Annual Report, Philadelphia: Get Healthy Philly (2015).

6. “Issue: State Food Purchase Program,” Greater Philadelphia Coalition Against Hunger, accessed October 16, 2016, http://www.hungercoalition.org/issue-state-food.

7. “Fiscal Year 2017 Budget Testimony," Philadelphia Department of Public Health (PDPH), Philadelphia City Council (May 3, 2016), http://phlcouncil.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Public-Health-Testimony-May-3-2016.pdf.

8. “Cost of Food at Home at Four Levels, U.S. Average, July 2016,” United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (July 2016), accessed October 16, 2016, https://www.cnpp.usda.gov/sites/default/files/CostofFoodJul2016.pdf.

9. "The Inefficiences of Attention Allocation," in The Politics of Attention: How Government Prioritizes Problems, by Bryan D. Jones and Frank R. Baumgartner, 285-286 (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2005).

Notes

i. Defined as: murder and nonnegligent homicide, forcible rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, motor vehicle theft, larceny-theft, and arson