Merely mention the ‘M’ word in nonprofit circles and either heads nod or bodies shudder. The choice seems binary: either go it alone or m-m-m-m-m-merge. We look to our for-profit counterparts and see instances of greater market presence, scalable operations and greater returns, or painful lessons with takeovers, layoffs, vanished identities and lost personal connections to the customer.

Fortunately for us, there is a wide range of options along a continuum through which nonprofits can affiliate between these two points. These include one-off or ongoing partnerships, shared purchasing, subsidiaries, strategic alliances, creating a holding company, and joint ownership of a new venture. The question is this: How do you deconstruct your options in order to make the right choice for your organization at the right time, and that that choice includes continuing to function as an independent, stand-alone entity? This is a seemingly simple question but with greater complexity than initially meets the eye.

Fairmount Ventures has facilitated numerous affiliation discussions among a wide variety of nonprofits over the past two-plus decades, some of which have resulted in highly effective partnerships, affiliations and mergers, and others which have concluded with everyone deciding to just be friends. The business case for an affiliation or merger is fairly easy to discern with a deliberate amount of due diligence: will you be able to serve more people, expand geographic reach, improve quality, attract more donations, create economies of scale, attract and retain a higher caliber staff, raise our visibility, influence the field, etc.? Our experience is that there are two essential factors to consider:

- Compatibility of organizational culture

- Board members’ psychic income

Ignore these at your peril.

Our profit-driven private sector counterparts understand this. Legally, if not always in practice, for-profit companies are accountable to their shareholders. This provides the rubric for decisions. Successful businesses regularly assess the market to reposition existing products, launch new ones and implement strategies to increase market share. The ostensible purpose and ultimate metric is to increase value for shareholders over the near and longer term. Still, when smart companies consider a merger, they evaluate a variety of criteria, with company culture near the top of the list. They realize that culture is a significant factor in a company’s value and plays a role in a merger’s success. Company culture includes core values, collective worldview, innovation perspectives, productivity expectations, methodology, leadership style and more. Many notable mergers have failed because companies did not exercise due diligence beyond financials, which resulted in plummeted stocks, employee exodus and tarnished brand reputations.

Nonprofits have a different, arguably more complex set of stakeholders than their for-profit counterparts, but there are lessons to be learned. Regardless of the impetus for considering a merger or affiliation—stagnant funding streams, rising competition from local or national organizations, shifts in public policy, major leadership shifts—cultural fit should be considered early on in discussions with a potential merger or affiliation partner. Sometimes, this can be the direct topic of conversation and other times, it is gleaned through observation, i.e., how an organization talks about its work, interacts or describes their worldview. Leadership must ask thoughtful questions about elements of their prospective partner organization’s core values, organizational dynamics, etc. in order to assess and clarify whether a merger or affiliation is the optimal solution.

I, of course, learned these lessons the hard way. About five years ago, I was asked to facilitate a merger between three organizations in contiguous geographic areas all part of the same national organization, with the same funding streams, providing similar services to the same types of populations, albeit with enough differences to make for some great synergies for program expansion. One of the executives was retiring and had no internal heir apparent. The other two executives tentatively agreed on how leadership would be shared. Everything made perfect sense, except that one of the executives was a bit of a goof ball. Literally. On occasion, he would bring a small ball to our strategy sessions and throw it in the air and catch it while we were mapping and modeling the new organization. At the eleventh hour, the other executive realized that Mr. Ball Thrower was not someone with whom he could work. The ball was not the real problem, but it revealed itself as an embodiment of larger issues. In retrospect, we should have called the issue – a strike? – much earlier.

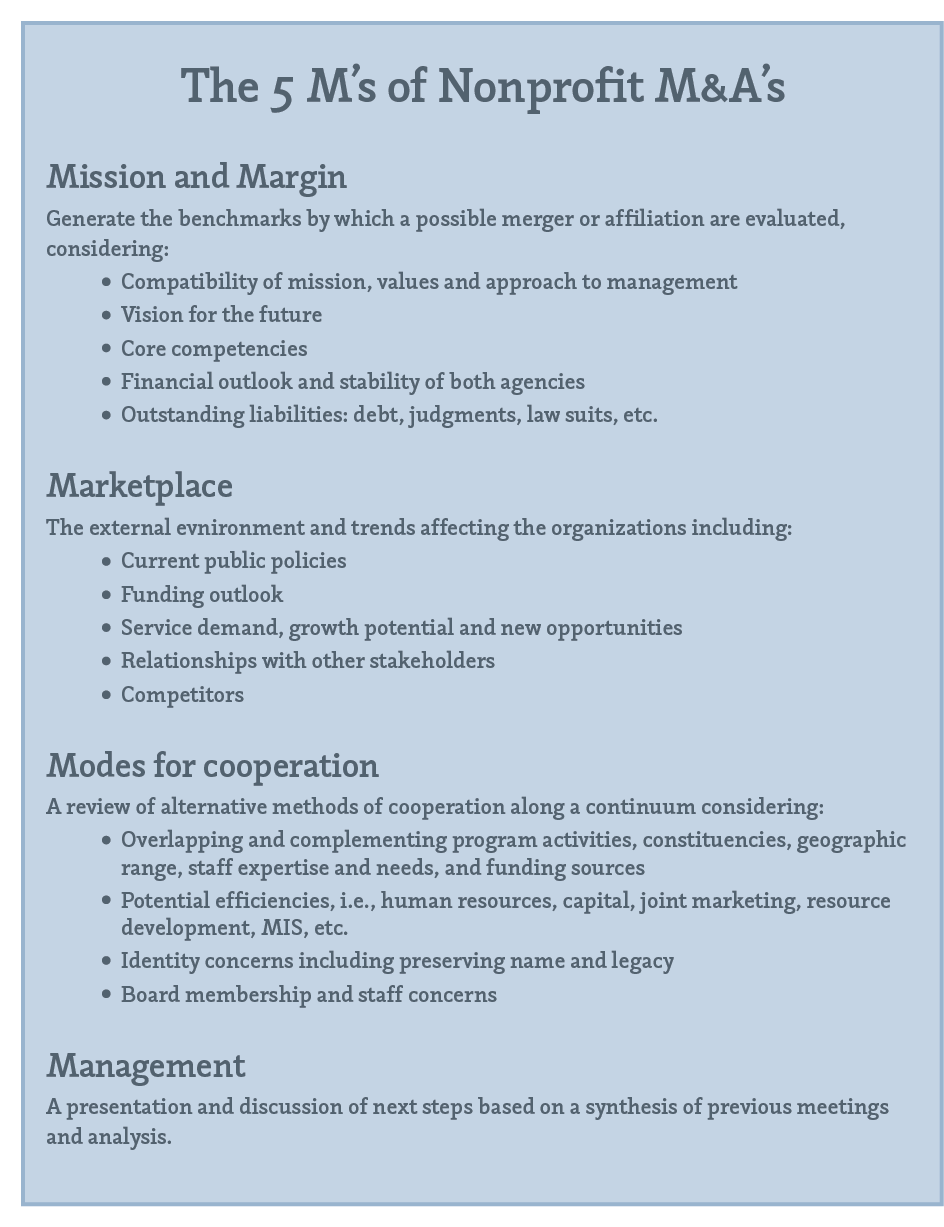

Culture may be a bit like the Supreme Court’s view of pornography, hard to define but we know it when we see it. Our experience is that initial merger and affiliation discussions should be focused and time limited, with culture being a major underlying issue constantly under surveillance. To structure the discussion and get at the culture issue without necessarily discussing it head on, Fairmount Ventures developed a process that we’ve dubbed “the five M’s”: 1) Mission, 2) Margin, 3) Marketplace, 4) Models for cooperation, and 5) Management. These topics help to set the agenda for a defined set of meetings in order to frame and focus the discussion on commonalities and potential conflicts that are likely to have direct impact on the partnership, while at the same time getting at culture.

While taking stock in the potential partner’s culture, board members need to look within themselves. People join nonprofit boards for many reasons, and if they remain active and engaged, they derive personal benefit from their participation, whether that’s advancing a goal about which they are passionate, learning, advancing their connections and careers, having a social outlet, feeling good about themselves or a combination of these. We’re not judging, but we are observing that board members derive psychic income in exchange for their service. So, what happens if you ignore this and try to take this benefit away?

Again, this is a case of learning from a mistake made about two decades ago that has been reinforced over the years of Fairmount Ventures’ facilitating nonprofit merger and affiliation discussions. Two long-standing organizations, also part of the same national organization, providing the same services with the same funding sources in Philadelphia decided to explore a merger. Both executive directors were retiring, and the national organization and major foundations wanted just one entity doing the work. One organization’s budget was ten times larger than the other, so while they discussed a merger of equals, the larger group tacitly viewed the dialog as an acquisition. Fast forward many months of discussion and we had an agreement, a new executive recruited from Chicago who was courted at the Four Seasons by major foundation presidents to come to Philadelphia and a champagne reception to honor the agreement. Then we sat down to discuss who would be on the board. The board of the larger organization realized that the smaller organization had a more engaged board and that they, as board members, would no longer run the show. They walked away.

While board members are considering the organization’s mission, services, finances, growth potential, market place, legacy, and even culture, they are less often being explicit about their own emotional stake in the organization as currently structured. Their passion for the organization’s mission and their ability to be influencers and connecters for the organization are valued benefits of board membership. Chances are that the board members involved in affiliation discussions are the leaders and more active members. Their internal narratives, as well as public personas, include being board members and leaders.

Even before the value proposition for pursuing a particular affiliation or merger begins, it is wise to have an explicit conversation among board members regarding what the possible change means to them. The conversation need not be awkward if properly facilitated, but let it be awkward if it needs to be. What’s more important: the organization’s mission and people served, or board members not wanting to have an uncomfortable conversation?

The key is to get the board involved in the discussion at the outset, keep them informed throughout the process, and help them envision how the new configuration can create a narrative and situation of equal or greater benefit to them as board members. This relationship management is not to pander to egos but rather to acknowledge that board members—the ultimate decision makers regarding a merger or affiliation—have a complex relationship with the organization even though they are ostensibly “just” volunteering their time and philanthropic support.

Achieving the optimal solution to a potential merger or affiliation in the nonprofit sector requires negotiating matters of the heart as well as of the head. These include the value proposition in the business arrangement, as well as the trickier aspects of organizational culture and board members’ engagement. Navigate them both with equal care.