Background on Substance Abuse

Substance abuse is a complex problem that, like many other social problems, is complicated to navigate, and relevant interventions are hard to implement. Substance abuse has an immense effect, as outlined by the American Psychiatric Association (APA), which defines substance abuse as “a maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress as manifested by one (or more) of the following [criteria], occurring within a 12-month period,” including “recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home (such as repeated absences or poor work performance related to substance use), recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous (such as driving an automobile or operating a machine when impaired by substance use), recurrent substance-related legal problems” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000, p.199). The APA further defines the impact on the individual as including “tolerance, withdrawal, a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use, a great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from its effects, important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use” (American Psychiatric Association, 2000 p.197). Treating this population is difficult and draining on limited resources.

Public services provided for individuals suffering from substance abuse disorders in Philadelphia have been lacking since the crack epidemic of the 1980s. All major urban centers including New York and Chicago were underequipped and undereducated to handle this sweeping drug. As this powerful stimulant is hitting the streets of Philadelphia in the early 1980s, we meet Virginia. Virginia is a 16-year-old African American teenager born in South Philadelphia. By her 16th birthday, Virginia is already a single mother and experimenting with speed pills, alcohol and benzodiazepines (medications normally prescribed for anxiety disorders). By the time Virginia is 17, she has become a sex worker at a nude modeling studio to survive and finance her drug habit. In just a few years the crack cocaine began to take its toll on Virginia’s life, and she is forced out of the high-end brothel onto the streets of North Philadelphia for a fraction of her previous rate. At this point, Virginia has several arrests for prostitution and drug possession, and, also during this time period, she has become estranged from her family and young child.

In this same era, Interim House is already over a decade old and struggling to keep its doors open. Interim House was founded by Clara Baxter Synigal, an African American woman and recovering alcoholic who realized the importance of gender-specific treatment owing to her personal experience with treatment for alcoholism and the difficulty she experienced sharing about sensitive issues in mixed-gender programs. At its inception, Interim House was one of the first women-only substance-abuse facilities in the country. With the economic downturn of the 1980s and the introduction of crack cocaine, Interim House is also overwhelmed. With only a single revenue stream to depend on, the city of Philadelphia, the outlook is bleak. In 1989, Interim House became an affiliate of PHMC (then The Philadelphia Health Management Corporation) to keep its doors open. The executive director of Interim House, Kathy Wellbank, describes this as a turning point for the agency.

Over the next 15 years, everything changed for Interim House. With the assistance of PHMC, including its infrastructure and back-office support, Interim House was able to diversify its revenue streams, receiving grants from a variety of public and private organizations over the years. Sources have included the Pew Charitable Trusts and donations from the United Way of South Eastern Pennsylvania. These donations and grants also expanded the clinical services offered. Interim House also received funding to provide psychiatric services to its clientele. The offering of psychiatric services alongside of drug and alcohol counseling is key for the clients with co-occurring mental health issues. Without these psychiatric services, women at Interim House could experience undiagnosed mental health issues that would lead to relapse and failed attempts at recovery. During this same time period, through the leadership and guidance of PHMC, Interim House received funding from Philadelphia Department of Human Services for services to be provided to the children of mothers in Interim House programs.

Substance abuse affects not only the identified patients but also those around the user. Substance abuse within the family unit can also have profound effects on other members of the household, especially children. These children face biological, psychological and environmental risk. The effect on children of family substance abuse is not isolated to the children who live with the abuser. Even children who don’t still live with the substance abuser face a number of stressors (Barnard & McKeganey, 2004). When there is intensive drug use in the home, there is always the risk of poor hygiene, lack of proper child supervision and lapses in child healthcare. These are frightening facts considering that over 6 million children under the age of 18 live with at least one parent who is dependent on alcohol or drugs (SAMHSA, 2003). Each of these additions to the agency is indicative of an agency evolving with the speed of research to provide cutting-edge clinical services to its patients and a dynamic family program driven by sound resource development.

While PHMC and Interim House are enjoying growth in the early 2000s through their strategic partnership, Virginia’s story is going from bad to worse. Virginia has been arrested a dozen times, served jail terms in county and state prisons, overdosed seven times and had four failed attempts to find sobriety. Her fourth attempt is possibly the most dramatic and traumatic. Virginia was still a sex worker in North Philadelphia, working with undesirable characters to set up and rob johns. An empathetic police officer who knew Virginia had chased away a would-be victim/john and convinced her to go to the hospital and get some help. While at the hospital, Virginia was shocked find out that she was pregnant and that it was quite possible that her unborn child was also addicted to the illicit drugs she was using. Virginia began a methadone maintenance program, because the symptoms of withdrawal from opiates (like the street drug heroin) can cause miscarriage. After 18 months drug free, Virginia experienced a crushing relapse, losing again the relationships with her family and her two children. By 2006, Virginia was back on the streets addicted to drugs and soon back in the criminal justice system.

The very next year, in 2007, staff grant writers at PHMC helped Interim House obtain a grant from the Pew Fund Capacity Building Program. Funding from Pew allowed IHI to implement a comprehensive, evidence-based training and supervision model that helps clients manage feelings, urges and behaviors in a constructive manner (Linehan, 1994). Integrating dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) techniques into the agency’s clinical practices helped meet the needs of the increasing number of women with serious mental health disorders. With this increased clinical capacity, IHI was able to improve the clinical outcomes of its clients, increase the clinical knowledge and capacity of IHI staff and reduce the stresses experienced by its staff in working with these high-acuity clients. The program was so successful after its first year that it has expanded to include ancillary and clinical staff.

Interim House has also quadrupled its resource stream, now receiving funding not only from the Pew Charitable Trust and the United Way but also Woman’s Way, the Genauridi Family Foundation, The Barra Foundation, The Northwest Foundation and the Patricia Kind Family Foundation. Interim House is now an innovative agency providing first-rate services. Also in 2007, Virginia is now making another attempt at recovery; after another year of her life spent in the Philadelphia Prison System, she has been paroled to the new and improved Interim House.

At Interim House, Virginia is treated by master’s-level clinicians and a psychiatrist discovers an underlying diagnosis of depression. Virginia credits Interim House with teaching her the tools she needed to be successful in the world. IHI is now also offering a step-down outpatient program through which a client who dischargers from the program can come back a few nights a week to continue clinical services. Virginia took advantage of every program that Interim House offered, including faith-based services that she credits with increasing her engagement and outlook on life. Virginia is a woman who was arrested 19 times in her life, yet after only six months at Interim House she described herself as a new woman. Now almost six years sober, she currently works as a peer specialist at Interim House. Virginia strives to share her experience, strength and hope with the women who are at Interim House hoping to be the program’s next success story.

PHMC and Interim House, through their affiliation, were instrumental in providing the support needed to help save Virginia’s life. PHMC’s model to affiliate with nonprofit-aligned businesses dates back more than a decade, with Interim House being the first to affiliate. Unlike nonprofit mergers, in the affiliation model PHMC has adopted each organization retains its own 501(c)(3) status and federal tax ID number and files its own 990 and audit. When a new agency affiliates with PHMC, existing agency staff are usually retained and human relations policies are modified to match PHMC standards. Existing board members are retained, and two PHMC board members are appointed. Several infrastructure systems are added to affiliate agencies, including consolidation into a single-pay master system, information technology and marketing and branding.

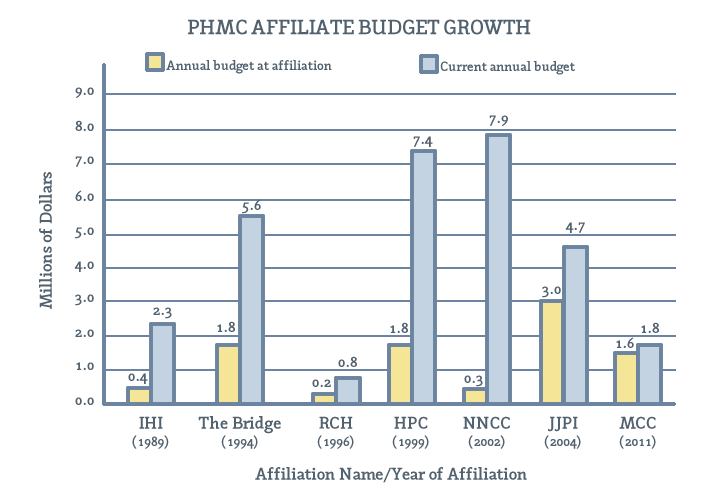

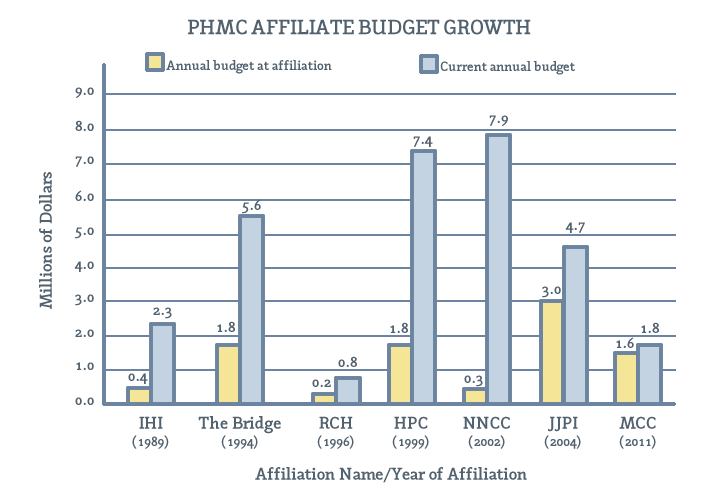

To date, the PHMC affiliation model has proven to be fairly effective. Most of the nonprofits that have affiliated (seven to date) have seen their budgets increase five- and sixfold. PHMC operates other agencies with less than 7 percent overhead and has a solid management and back-office infrastructure to support these affiliate nonprofits.