Introduction

Research for Action (RFA) has a long and rich history of studying the nuance, context and consequences of Philadelphia’s efforts at urban school reform, especially with an eye toward the role of community organizing and civic engagement in calling for significant reforms. It was with that lens that RFA, in collaboration with a New York partner, Dr. Jeffrey Henig of Teachers College, embarked upon a two-year inquiry to study the effects of the Donors’ Education Collaborative (DEC) and its investment in school reform efforts. DEC is a joint grantmaking effort that since 1995 has supported policy reforms aimed at making the New York City public school system more equitable and responsive to the needs of all children. The collaboration of research, organizing, advocacy and policy groups funded by DEC, which took shape to become the Campaign for Better Schools, sought to interject authentic parent and community voices into the debate about mayoral control of New York City’s public school system.

This is a story of advocacy and organizing that parallels the sustained efforts of education groups and coalitions in Philadelphia and other large cities. The competition of ideas, strategies and negotiations in a fast-paced political arena offer valuable lessons learned, especially as dramatic education reform initiatives take root in cities and states throughout the country. Perhaps those lessons learned come not only from the Campaign’s policy victories, but also from its trials and successes in pursuit of long-lasting, sustainable education reform.

Origins of the Study

The Donors’ Education Collaborative (DEC) has supported a range of groups – advocacy, organizing, research and policy groups – that advocate for, or have members from, diverse constituencies concerned about public education in New York City (NYC). DEC has also encouraged collaborations among these types of groups to leverage their influence on education policy at city and state levels. The groups, consisting of youth, parents and community leaders, operate in all five NYC boroughs. Some focus solely on education issues, while others have multi-issue agendas. They include groups representing African Americans, Asian-Americans and Latinos, as well as a range of immigrant and refugee populations.

In anticipation of the June 2009 sunset of mayoral control of the NYC schools, and the passing of new legislation that would maintain, change or end mayoral control, DEC sought to encourage a robust public debate about school governance. In late 2007, DEC funded the Alliance for Quality Education (AQE) to plan with the Coalition for Educational Justice (CEJ), the Community Involvement Project of the Annenberg Institute for School Reform (CIP), and the New York Immigration Coalition (NYIC) for a partnership that would develop a coalition to bring a public voice to the school governance debate. In Spring 2008, following the initiating groups’ planning process, DEC commissioned an evaluation of the implementation and impact of the coalition they would build on the debate and the outcomes, as well as on the broader NYC educational policy environment. This Executive Summary covers the findings of the two-year study period, May 2008 through May 2010. The overall question that the study seeks to answer is:

In what ways does DEC’s sustained investment in advocacy, organizing, research and policy groups that include and advocate for minority and immigrant families contribute to a broader public understanding and a richer, more informed and more democratically responsive debate about NYC school governance and policies?

We raise this question in the context of the significance of “civic capacity” for the sustainability of school reform. A community with civic capacity is one in which groups work across sectors to identify a shared agenda and to mobilize the human and financial resources required to forward that agenda. Considerable research has suggested that school districts in cities in which significant civic capacity is present are those in which reforms are most likely to be sustainable. Thus, the report examines the impact of DEC’s funding in terms of whether the coalition, called the Campaign for Better Schools, succeeded in its policy goals, but also draws conclusions about whether DEC funding has advanced the longer term development and sustainability of a collaborative and effective civic sector engaged in an ongoing role in school reform. An interdisciplinary team of researchers used a qualitative research approach employing multiple methods of data collection, including an examination of public opinion polls; a media scan; and extensive fieldwork with a broad range of policy makers and observers, and political actors, including Campaign members as well as other education advocates and activists.

Introduction

Research for Action (RFA) has a long and rich history of studying the nuance, context and consequences of Philadelphia’s efforts at urban school reform, especially with an eye toward the role of community organizing and civic engagement in calling for significant reforms. It was with that lens that RFA, in collaboration with a New York partner, Dr. Jeffrey Henig of Teachers College, embarked upon a two-year inquiry to study the effects of the Donors’ Education Collaborative (DEC) and its investment in school reform efforts. DEC is a joint grantmaking effort that since 1995 has supported policy reforms aimed at making the New York City public school system more equitable and responsive to the needs of all children. The collaboration of research, organizing, advocacy and policy groups funded by DEC, which took shape to become the Campaign for Better Schools, sought to interject authentic parent and community voices into the debate about mayoral control of New York City’s public school system.

This is a story of advocacy and organizing that parallels the sustained efforts of education groups and coalitions in Philadelphia and other large cities. The competition of ideas, strategies and negotiations in a fast-paced political arena offer valuable lessons learned, especially as dramatic education reform initiatives take root in cities and states throughout the country. Perhaps those lessons learned come not only from the Campaign’s policy victories, but also from its trials and successes in pursuit of long-lasting, sustainable education reform.

Origins of the Study

The Donors’ Education Collaborative (DEC) has supported a range of groups – advocacy, organizing, research and policy groups – that advocate for, or have members from, diverse constituencies concerned about public education in New York City (NYC). DEC has also encouraged collaborations among these types of groups to leverage their influence on education policy at city and state levels. The groups, consisting of youth, parents and community leaders, operate in all five NYC boroughs. Some focus solely on education issues, while others have multi-issue agendas. They include groups representing African Americans, Asian-Americans and Latinos, as well as a range of immigrant and refugee populations.

In anticipation of the June 2009 sunset of mayoral control of the NYC schools, and the passing of new legislation that would maintain, change or end mayoral control, DEC sought to encourage a robust public debate about school governance. In late 2007, DEC funded the Alliance for Quality Education (AQE) to plan with the Coalition for Educational Justice (CEJ), the Community Involvement Project of the Annenberg Institute for School Reform (CIP), and the New York Immigration Coalition (NYIC) for a partnership that would develop a coalition to bring a public voice to the school governance debate. In Spring 2008, following the initiating groups’ planning process, DEC commissioned an evaluation of the implementation and impact of the coalition they would build on the debate and the outcomes, as well as on the broader NYC educational policy environment. This Executive Summary covers the findings of the two-year study period, May 2008 through May 2010. The overall question that the study seeks to answer is:

In what ways does DEC’s sustained investment in advocacy, organizing, research and policy groups that include and advocate for minority and immigrant families contribute to a broader public understanding and a richer, more informed and more democratically responsive debate about NYC school governance and policies?

We raise this question in the context of the significance of “civic capacity” for the sustainability of school reform. A community with civic capacity is one in which groups work across sectors to identify a shared agenda and to mobilize the human and financial resources required to forward that agenda. Considerable research has suggested that school districts in cities in which significant civic capacity is present are those in which reforms are most likely to be sustainable. Thus, the report examines the impact of DEC’s funding in terms of whether the coalition, called the Campaign for Better Schools, succeeded in its policy goals, but also draws conclusions about whether DEC funding has advanced the longer term development and sustainability of a collaborative and effective civic sector engaged in an ongoing role in school reform. An interdisciplinary team of researchers used a qualitative research approach employing multiple methods of data collection, including an examination of public opinion polls; a media scan; and extensive fieldwork with a broad range of policy makers and observers, and political actors, including Campaign members as well as other education advocates and activists.

A Strong Beginning: Diversity, Collaboration, and Strategic Compromise

The Campaign’s first year focused on building the coalition, developing a platform, and planning the campaign. The process was complex and multi-faceted, and faced many challenges, but the Campaign also began with some distinct advantages: (1) DEC had previously funded the initiating groups, so that they came into the effort with a history of collaboration and mutual trust, and an ability to work cooperatively through the challenges; (2) targeted DEC funding for the Campaign enabled the coalition to come together early, engage deeply with the issues, and develop the necessary staff infrastructure to carry through on plans and ensure coalition effectiveness; and (3) the coalition included a diversity of participants from throughout the city, including groups representing a variety of geographic areas, populations newly seeking to be heard in the education policy discussion, and a range of skill sets and networks.

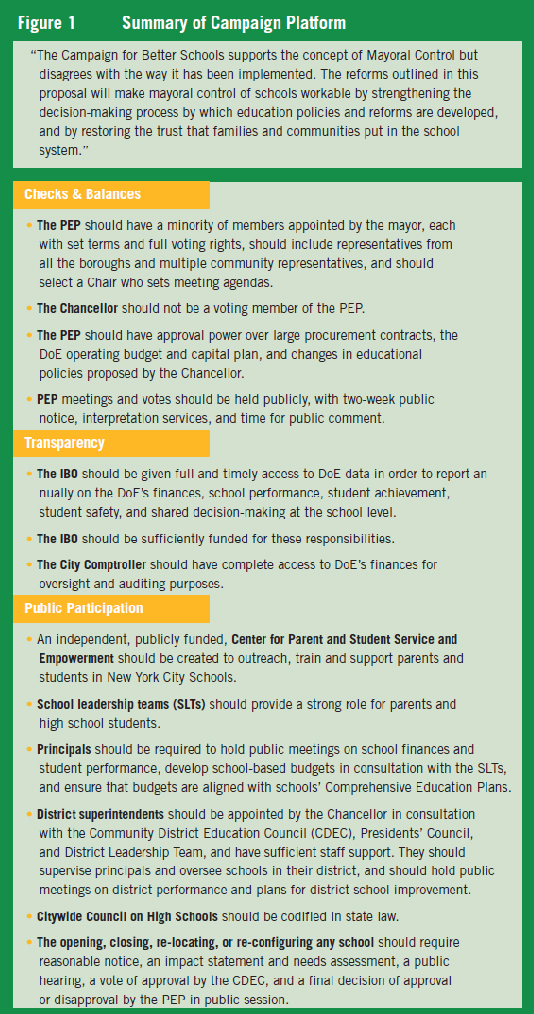

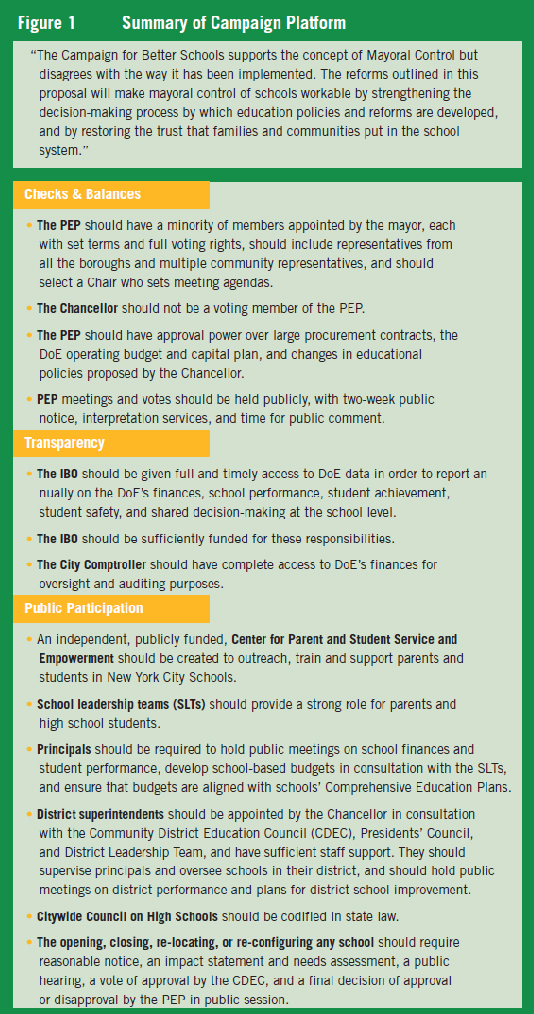

From its inception, the Campaign sought to balance principles and pragmatism in positioning itself on mayoral control. Although Campaign members shared a strong concern about the unchecked power of the mayor under the existing legislation, they were also sensitive to the political climate which characterized any alternative as a return to the previous governance system, widely criticized as lacking clear lines of accountability. Mayor Bloomberg’s bottom line in the debate was that he should exercise mayoral control, with no change in the composition of the critical policy making body—the Panel for Educational Policy (PEP). Campaign leaders took the strategic position to advocate for continuing mayoral control albeit with significant changes, especially in regard to the PEP. In this way, Campaign members sought to strike a middle ground and ensure they would be perceived as “in the game.” This positioning of the Campaign became key as the political debate progressed; it enabled the Campaign to adjust strategy along the way in order to secure some “wins” in the final legislation. The final platform from which the Campaign worked reflected priorities for checks and balances, transparency and public participation. This platform is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Campaign Execution: A Changing and Challenging Environment

The Campaign came out of the gate with its official launch in November 2008, to face many anticipated and unanticipated challenges.

Competing Voices.

The Campaign competed for authority and attention with other groups seeking to claim the mantle of speaking authentically for New York’s parents and community members. Learn NY was strongly in favor of mayoral control; it claimed to be independent of the mayor, but it had strong ties to the administration and its backers. The Parent Commission on School Governance and Mayoral Control drew its members mainly from among parents serving on formal education system bodies, such as the Community Education Councils (CECs), School Leadership Teams (SLTs) and President’s Councils. They believed that mayoral control should end with the sunset of the mayoral control law. Our media analysis tracked media coverage of all three groups. With its more nuanced approach to mayoral control, and parent spokespeople able to represent it, the Campaign emerged prominently and consistently in a broad range of media sources as the group recognized as authentically speaking on behalf of parents. DEC funding amplified the Campaign’s voice, not only by providing the ability to hire paid staff to help keep up momentum, but through the support of a media consultant who helped the Campaign hone its messages, time its events, and expand member groups’ already substantial media and legislative contacts.

The Paradigm of Public Engagement.

The Campaign’s platform recommendation for expanding public engagement directly challenged the administration’s paradigm for parent participation, in which parents were encouraged to be involved in their children’s education and to provide assistance in implementing District policies. The Campaign’s conception of engagement emphasized a greater parental role in policy decision making. The mayor’s and chancellor’s position that any alternative paradigm risked a return to the discredited era of decentralization, a period associated with greater community participation, challenged the Campaign as it worked to reframe the public participation issue.

Policy Context.

The Campaign had to adapt to a national policy climate conducive to continued concentration of educational authority in the mayor. National education policy was taking shape in parallel to the debate around mayoral control of NYC schools, and Education Secretary Arne Duncan was a strong and credible supporter of mayoral control in NYC and nationwide. This national support set a powerful positive tone for strong mayoral control that was challenging to counter.

Political Uncertainty.

The Campaign had to adjust to the upset in business as usual in Albany due to the June 2009 shift in party alliances that temporarily changed the balance of power in the NY State Senate. They had to maintain solidarity, focus, and excitement in a volatile political atmosphere while participating in a high stakes, complex policy issue. The challenges of this situation only intensified further when the legislature was unable to act before the June 30th date for sunset of the existing mayoral control legislation. The speed and complexity that characterized unfolding events increased significantly and extended the work of the Campaign beyond the period of DEC funding. Compounding the challenge were the unexpected endorsements in May 2009 by UFT president Randi Weingarten and Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver of Bloomberg’s definition of mayoral control, which realigned the political players in unforeseen ways.

Through its extended and collaborative platform development process in the first year of the initiative, the Campaign built solidarity among the groups that largely endured through the challenges. Inevitably, however, the policy environment and political uncertainty created tensions within the Campaign that had to be navigated. These included: (1) dissatisfaction with the communication between the Coordinating Committee, comprised of six leadership groups, and the larger Steering Committee representing all the groups, as the pace of the legislative debate increased the need for nimble strategic responses in order to exercise maximum leverage in Albany. The highly consultative decision-making process that had characterized platform development in the first year was not adaptable to the politicized environment in which the Campaign was working in its second year; (2) differing perspectives between strategy-oriented and process-oriented groups, where the former brought skills in navigating the political terrain and the latter brought mobilizing strength; and (3) political and funding pressures on multi-issue groups, which had to balance their Campaign participation with advocacy regarding non-Campaign issues and the groups’ important relationships with the Department of Education (DoE) and other city agencies. The Campaign did not ignore these tensions; rather, Campaign leaders and members acknowledged and addressed them by bringing the partners together to exchange views and reinforce their mutual trust and good will. Campaign participants were able to look beyond the immediate situation to their long-term interest in future work together to strengthen the public schools.

Legislative Outcomes

The Bloomberg administration capitalized on public perceptions of the previous NYC public school governance arrangements as flawed and corrupt, painting anyone who might oppose mayoral control with wanting to return to those conditions. They had significant backing and resources to advocate for this position. Yet, legislators and their constituents had high expectations that new legislation would address issues of concern including unchecked mayoral authority, lack of parent and community input into decision making, and insufficient transparency around data collection and reporting.

The Campaign platform’s position not to oppose mayoral control completely while calling for changes to the PEP was central to Campaign strategy to constrain the mayor’s authority, although recommendations concerning transparency and public participation were also intended to shift the power balance (see Figure 1 above). In the fall of 2008, few of the players believed that parent and community groups would be organized enough to influence the legislative process, and Campaign leaders knew the PEP recommendations would be difficult to achieve, given the mayor’s opposition. In the end, the Campaign did not prevail in this matter. However, the Campaign’s adoption of PEP change as its “leading edge issue” ultimately provided a significant strategic advantage. By challenging the makeup of the PEP, the Campaign opened a space in which a broader debate could occur about the extent of the mayor’s authority, and in the end helped pave the way for the platform’s recommended changes to the law around transparency and public participation that would check the power of the mayor.

Although the media treated the new bill, which finally passed in early August 2009 (more than a month past the sunset deadline), as a victory for the mayor, Figure 2 summarizes the key provisions of the final bill vis-à-vis the Campaign platform and shows a more mixed outcome.

The provisions around transparency closely matched recommendations made by the Campaign. They are important because they are expected to make a difference in the accountability of the administration. Provisions around public participation for which the Campaign had advocated strongly were also in the “win” column, especially the amendment that promised support for a parent training center and student success centers to help parents and young people strengthen their education policy voice, as well as requirements for public hearings and impact statements around proposed school closings.

The Long Term Effects of the Campaign’s Efforts and the Mayoral Control Debate

Fully evaluating the long-term consequences of the process and outcomes of the mayoral control debate is not possible at least until after the next election cycle has run its course and a new administration demonstrates whether it will build upon or sharply reconfigure the education changes initiated under Mayor Bloomberg and Chancellor Klein. Nevertheless, there are developing trends that have emerged from the battle over mayoral control, including:

A Changing Political Environment.

In November 2009, Michael Bloomberg won reelection to his third term, although by an unexpectedly small margin, with 55 percent of public school parents voting for his opponent. Nevertheless, Chancellor Klein cited the mayor’s education policies as a clear contributor to his victory. At the same time, however, opponents of mayoral control had used the debate over the renewal legislation to coalesce around many of the issues cited in the Campaign’s platform, and candidates for other offices—most notably the Public Advocate and the Comptroller—featured criticism of the mayor and chancellor in their successful campaigns; they continue to position themselves for future elections as advocates of change in the mayoral control regime.

Challenges to the Mayor’s Claims and Authority.

Over the course of the mayoral control fight, the increasing prominence of the parent and community voice in the media diminished the administration’s ability to keep discontent muffled or marginalized. The Campaign posed substantial challenges to administration claims of sharp student performance gains, and was able to educate legislators and their staffs, as well as the media, to be more knowledgeable about this issue.

Outcry about School Closures.

Perhaps the most dramatic mark of the changing landscape was the January 2010 PEP meeting on 19 planned school closures. The meeting was attended by 2,000 people and covered by all of the major media sources in the city. The groups that orchestrated the mobilization of parents to attend the meeting were able to work from momentum and contacts developed during the battle over mayoral control, facilitated by requirements in the new law for impact statements, advance notice, and public comment.

Reframing the Question.

Prior to the Campaign, the administration controlled the policy question—should there be a continuation of mayoral control as it has been shaped by the mayor and chancellor or should we return to the days of decentralized school boards? The Campaign’s politically sophisticated and more nuanced view of the debate demonstrated the potential of a well-prepared and adequately resourced coalition to project a unified voice and opens the possibility for a new frame of the mayoral control debate as it plays out through Bloomberg’s third term and beyond. The Campaign brought fresh and authentic voices to the conversation that could not be labeled as defenders of the old days.

Broadened and More Diverse Networks.

Because of the Campaign, participating groups developed new relationships, expanded their networks, became aware of a range of previously unfamiliar viewpoints and communities, and increased their visibility. The experience of the Campaign will make it easier to reignite ties and cooperative relationships when an important challenge or opportunity appears; some of that activity has already happened post-Campaign.

Deeper Policy and Legislative Expertise.

The groups’ experiences in the Campaign have developed their expertise and sophistication in the policy and legislative arenas both within and potentially beyond the confines of education policy. The lessons of the mayoral control battle are likely to make the individual coalition organizations more effective not only the next time they join together but also in their own ongoing efforts to affect policy. Some groups felt that they had paid a price in terms of their relationship with City Hall and the DoE around their non-Campaign issues, but others felt they had learned more about how to communicate with the authorities and gained some credibility with the administration that saw them now as more of a force to be reckoned with.

All of these elements taken together make a strong case that the Campaign’s sustained involvement in the debate has served to further develop the civic capacity of the groups within the coalition, and changed the environment in which those groups interact with policy makers.

Conclusion: The Impact of DEC Funding

As we began research for this evaluation in May 2008, most knowledgeable observers bet that the long-time political formula for getting things done in Albany would prevail. They largely dismissed the possibility that community-based groups with a different agenda than the mayor’s would have any significant influence on the legislative outcome. Our research suggests, however, that the conventional wisdom did not hold. DEC’s backing of a community-based coalition was instrumental in repositioning the mayoral control debate into one about checks and balances, transparency and public engagement. The Campaign engaged significant numbers of parents and community members in the debate who would not otherwise have been involved, mobilized a counter force to Mayor Bloomberg’s massive political force, and extracted important concessions in the final legislation.

Rather than funding a particular program or policy initiative—the standard operating procedure for many foundations—DEC’s approach has been to use its funding strategically to build a stronger base of active organizations focused on improving public education for all students. This approach enabled the recipient organizations and their partners to shape the debate as it unfolded in the year leading up to the legislative resolution, catalyzed the formation of the Campaign and an early mobilization of the coalition, and gave the Campaign visibility and the opportunity to influence how issues were discussed in the media and other public forums. In its first year, the Campaign gained public attention for its positions by strategically positioning itself not against mayoral control, but for improving it; by mobilizing and working with constituents all over the city; and by achieving status in the media as a legitimate voice for the interests of parents and community members that might not otherwise be heard. As the Albany phase of the battle heated up, the Campaign continued to act strategically in order to maximize its influence, and consequently achieved some significant “wins” in the final legislation. The potential of these legislative provisions to be influential in the long term is still dependent, however, on the extent to which increased capacity for parent mobilization and education can be built and maintained.

DEC support has been crucial to the process, creating the capacity for flexible and ad hoc coalition work, and providing funding for essential, if temporary, coalition infrastructure—e.g. staff and media relations. Such infrastructure enables constituency-based and interest groups to build civic capacity, through education about policy issues such as school governance, and by facilitating collaboration to affect policy at multiple levels of government. The Campaign showed that the type of funding DEC provided can assist grassroots coalitions in becoming an ever-growing circle, with groups that previously had little or no coalition experience gaining sophistication in coalition building and policy issues beyond their immediate interests.

The current national political environment for education policy making and advocacy presents challenges to the kinds of groups that made up the Campaign. It features an expanding role for federal and state government in local education, expansion of school choice and privatization, shifting demographics, and the declining power of local school boards. This environment requires that grassroots groups respond with new tactics that move beyond strictly local relationships and build effective ad hoc coalitions, even while maintaining their individual agendas.

In fact, the DEC funding strategy is promoting the kind of organizational capacity and response that this new environment requires. It is likely that the Campaign and its battle over mayoral control has left the member groups better prepared for the challenges of injecting a stronger and broader community voice into debates about future educational priorities and policies. Differences in perspective and core interests remain, of course. Yet, it appears that the level of communication, mutual understanding, and trust among the Campaign groups increased and may be sustained. For the member groups that most often operate at the local grassroots level, the experience provided greater understanding about political strategy. For those that find themselves strategizing in the corridors of power, the passion of the grassroots undergirded their often pragmatic focus. The Campaign was able to build its power by balancing the principles that mobilize action with the practicalities that allow for a strategic focus on achieving gains within the realities of the political moment.