Introduction

Southeast Asian Mutual Assistance Associations Coalition (SEAMAAC) and the African Family Health Organization (AFAHO) are two community-based organizations in Philadelphia that were formed by immigrant and refugee leaders. These organizations are based in different parts of the city and have target populations from different parts of the world; however, their approaches and foundational beliefs are similar. Both organizations’ programs are built around community needs, their multilingual staff reflect the populations that they serve, and their offices are in the heart of the immigrant and refugee neighborhoods that they work with. SEAMAAC and AFAHO see clients not as consumers, but as active partners in the goal of stronger families and stronger communities.

A tragic story highlights the gaps in services and systemic barriers that led to the founding of AFAHO. In 2002, a young, undocumented, and uninsured woman from Mali felt ill but hesitated to go to the emergency room to seek care due to her immigration status. After a few days, she started hemorrhaging but was still afraid to seek help. She died alone in her apartment in West Philadelphia. Her body was not found until neighbors started to smell a decomposing corpse and alerted the authorities. Her death seriously impacted the founder of AFAHO, Ms. Tiguida Kaba -- herself an immigrant from Senegal -- who was determined to create an organization where African and Caribbean immigrants and refugees could seek access to healthcare regardless of insurance and legal status. AFAHO works to address the needs of underserved, vulnerable, and hard-to-reach community members who experience difficulties accessing health services due to cultural, geographic, linguistic, the lack of insurance, and other barriers. AFAHO aims to mitigate their barriers to service delivery and facilitate access to preventive and primary care services in an effort to reduce health disparities and improve healthcare outcomes.

SEAMAAC was founded in 1984 by refugees from Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. The founding vision was to unite several of Philadelphia’s Southeast Asian organizations into a dynamic refugee-led coalition, enabling small ethnic communities to share resources and create a unified voice for the city’s Southeast Asian community. In 1998, SEAMAAC expanded its services to other immigrants and refugees as well as to native-born Philadelphians. Today, SEAMAAC’s mission is “to support and serve immigrants and refugees and other politically, socially, and economically marginalized communities, as they seek to advance the condition of their lives in the United States.”

In broad strokes, the barriers addressed by Philadelphia community-based organizations such as SEAMAAC and AFAHO are caused by social, economic, and political marginalization, defined as treatment of a group as peripheral or insignificant. Marginalization for immigrant and refugee families often results in social isolation and limited ability to access mental, physical, and social resources. Despite the timeframe of resettlement, diverse countries of origin, and cultural and linguistic differences, Asian and African immigrants and refugees face many similar challenges. Many are isolated, with little support and few resources to understand and navigate mental/physical health care and social service systems in the city. They are not easily reached through traditional outreach/education methodologies.

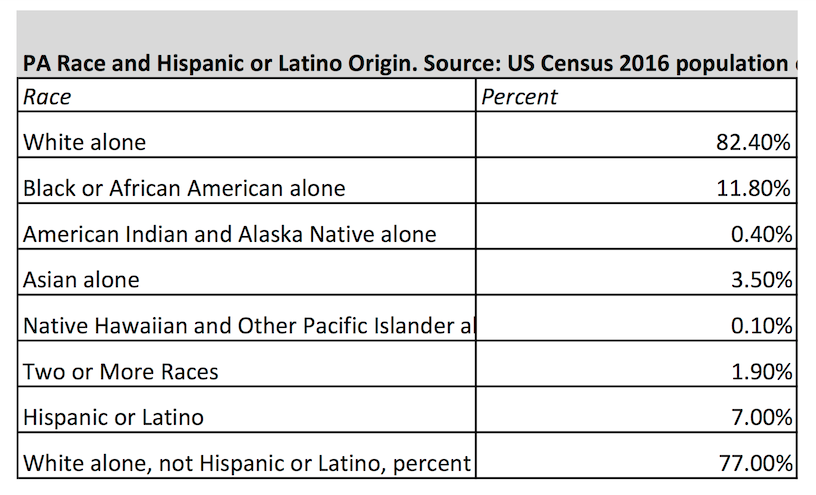

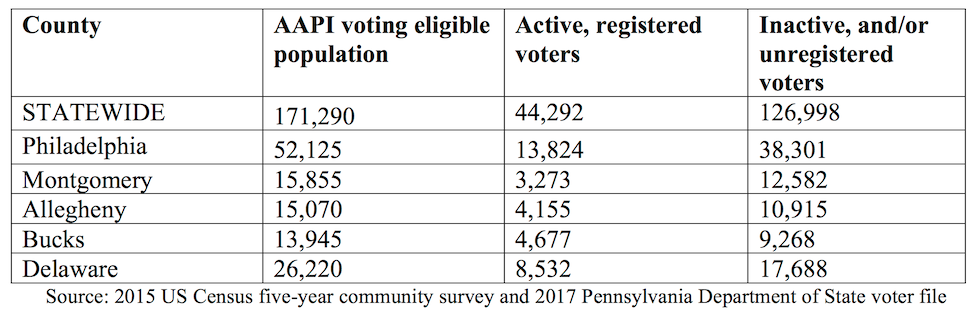

Lack of adequate data on immigrant and refugee communities creates an invisibility of need. For example, there are an estimated 50,000 African immigrants and refugees residing in Philadelphia, but there is a dire lack of information about the health needs and trends within this population. A key reason for this is that Census and other data embed information on African population groups (also called “foreign-born blacks”) within data on African Americans. For example, in the most recent Community Health Assessment completed by the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, there was no mention of foreign-born blacks when examining the racial and ethnic disparities that are evident across a range of health issues. This categorization is detrimental to the health and wellbeing of African immigrants and refugees as it limits the ability to fully understand their healthcare needs, practices, and the health disparities they face. Similarly, “Asians” are frequently lumped together as one monolith -- the “Model Minority.” This is a myth that fails to recognize the wide range of socioeconomic and health complexities of various Asian ethnic groups. As more Asian and African immigrants from a greater diversity of nations come to the United States and Philadelphia, public health research and interventions will need to adapt to an intentional focus on culturally-informed outreach, screening, prevention, and treatment of mental health and physical health issues.

Many Asian and African immigrants and refugees have traditionally interacted with health systems for acute care only. For these cultures, chronic disease is a relatively new concept and creates a different way of interacting with providers, especially in terms of the Western medical model. For example, although African immigrants and refugees are at a high risk for diabetes, hypertension, heart attack, and stroke, they are under a misconception that their diet is healthy and not a risk factor for these chronic diseases. In their home countries, Asian and African immigrants and refugees accessed healthcare services only as an option of last resort, relying mostly on traditional medicine and healers. Upon arrival in the U.S., Asian and African immigrants are healthier than their U.S.-born counterparts but their health deteriorates the longer they stay in the U.S. This can mostly be attributed to lifestyle changes including increased consumption of unhealthy foods (even traditional foods are now processed and packaged), a more sedentary lifestyle, and a drastic increase in stress, exacerbated by the lack of community and social networks.

Immigrants and refugees’ layers of traumatic experiences can develop into physical and mental health issues without adequate support. For example, Bhutanese refugee elders have expressed concern about learning English to pass the citizenship exam, and suicidal thoughts if they perceive that they would become a financial burden on their families. Experiences in their home countries, refugee camps, as well as family disruptions, compounded by the difficulties of straddling two cultures and the pain of being marginalized in this new land can result in high rates of depression, anxiety, and other mental health concerns (Gozdiak, 2004 and Ater, 1998). Adjustment to life in the United States is complicated by the traumas of war, forced separation from family, and the lack of opportunities to grieve for losses in the home country.

In June 2017, SEAMAAC conducted focus groups with immigrant and refugee elders on mental health and addiction that highlighted that the elders see these issues as significant concerns in their community. Contrary to frequent misconceptions, it is not that immigrant and refugee families are not interested in mental health services; it is that current mental health services are not accessible or culturally relevant. Mental health programming has not adapted to engage the communities on a cultural level, are not within the neighborhoods that immigrants and refugees reside, and are not offered in their primary languages. City offices, institutions, and service providers too often are not prepared to meaningfully extend their services to diverse immigrant and refugee populations.

Innovative Models of Service Delivery

Culturally-Specific Program Design: SEAMAAC and AFAHO’s family and community-based intervention and linkage services as well as our cultural and linguistic expertise have distinguished us as providers of unique and strategic services to Asian and African communities. The majorities of our clients have Limited English Proficiency (LEP), low-literacy rates, and are low-income, which further isolates them from mainstream information and awareness. Our activities focus on outreach, prevention, education, and bringing people into care early. SEAMAAC and AFAHO have maintained a presence in our communities through outreach, engagement, and building relationships with community establishments. As our target population relies heavily on its community leaders and representatives for information and resources, SEAMAAC and AFAHO have been able to utilize their mutually benefiting relationships with community leaders to spread awareness and leverage support for our services.

Over the years, SEAMAAC and AFAHO have developed, implemented, and managed several preventive and linkage to care health programs including diabetes and heart disease awareness and screening; nutrition and physical fitness education for children and their caregivers; maternal and child health; family planning; breast cancer awareness and linkage to screening; teen pregnancy prevention; Hepatitis B & C; and HIV/AIDS. Our activities focus on health and prevention education workshops for men, women, and youth; health literacy; ESL classes; facilitating access to regular screenings at our office and community locations; developing bi-lingual and bi-cultural educational materials; offering medical escort services to our LEP clients to aid with language and cultural interpretation; cultural competency trainings, and language translation and interpretation. Many of AFAHO and SEAMAAC staff members are immigrants and refugees and/or former clients; who can sensitively challenge some of the cultural norms that increase risk.

Peer Navigator Model: Another model of care used by AFAHO and SEAMAAC is the Peer Navigator model which includes outreach, health education and promotion, linkage to screening services, and language/cultural/system navigation support services. Peer navigators are trained to normalize highly stigmatized diseases and conditions including HIV, Hepatitis B & C, and breast cancer in order to connect their peers with screening and treatment. Utilizing street and venue-based outreach at locations including churches, mosques, women’s savings groups, ethnic women’s associations, hair braiding salons, and other community gathering places, multilingual/bicultural Peer Navigators can link medically underserved friends and neighbors with pertinent health information to dispel myths, improve awareness of health issues, mitigate barriers to care, and increase access to care. Peer Educators utilize storytelling and personal journeys during outreach and educational sessions to empower clients.

Elders Program Innovation: It is unusual for funders to offer financial support for culturally-specific needs that are invisible to those outside of the immigrant and refugee communities. Therefore, many of SEAMAAC and AFAHO’s programs began without funding, funneled via a recognition of needs within the community and goals to address these needs. For example, in 2007 SEAMAAC saw a spike in Asian refugee elders’ behavioral health issues including depression and attempted suicide. SEAMAAC responded by creating the Roots of Happiness: Elders Health & Wellness Program to reduce elders’ social isolation and support them to reclaim their lost status as respected elders. “Roots of Happiness” refers to cultural roots: language, arts, heritage, and communal meals. SEAMAAC began providing a weekly space for elders to gather and enjoy cultural heritage homemade meals. On a minimal budget and with volunteer engagement of elders themselves, the program has grown to include arts & crafts, cultural celebrations, leadership development, mental/physical health workshops, citizenship education, physical fitness, financial literacy, computer classes, case management, and intergenerational connections. Key to the success of the program is the “Elders Council” -- a group of program participants who volunteer to serve as peer leaders. They meet with program staff to debrief about program events, give suggestions about future activities, and recruit and mentor their peers. Elders Council members are essential partners in program development and evaluation. They volunteer alongside our bicultural/bilingual outreach staff to build community connections and trust -- and successfully provide education and support around culturally taboo topics such as abuse, addiction, sexual health, and mental health.

Laotian Elders enjoy breaking bread and connecting with the community at Key Elementary School in South Philadelphia on a chilly winter morning.

Utamaduni Wa Afya Program Innovation: There is a popular saying that “it takes a village to raise a child.” Likewise, AFAHO believes “it takes a village to improve one’s health.” AFAHO has begun exploring the benefits of using family members to promote healthy lifestyle changes among African immigrants and refugees dealing with chronic illness. Who could possibly have more interest in the health of a family member than another family member? This innovative model to improve health outcomes developed out of the understanding that African immigrants and refugees come from close-knit, family and community-oriented societies. Oftentimes, in African societies, family members serve as primary care providers. This was evident during the recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa where many people who lost their lives were family and/or community members caring for their loved ones. We aim to change this narrative into a positive one where family members are provided with the proper knowledge about how to assist their loved ones in making healthy lifestyle choices around nutrition and physical activity. Likewise, if an emergency happens, the family members are normally the first line of defense and should be educated on what to do to help, particularly in LEP populations. Not only does this “village” model improve the clients’ health, it improves the overall health of other family members with long term and possibly generational effects. With adequate funding and resources directed to planning and evaluation, AFAHO hopes to implement this Utamaduni Wa Afya (Culture of Health) model across all of its health programs.

Attendees at AFAHO’s Annual African Family Day

Photo Credit: Kiera Kenney

Domestic Violence Program Innovation: In 2011, SEAMAAC conducted an in-depth needs assessment of domestic violence in Philadelphia’s Asian communities. This included a literature review, examination of domestic violence projects in Asian communities around the country, and eight focus groups with members from Philadelphia’s Asian communities and domestic violence service professionals. A research intern helped SEAMAAC to develop a service model centered around bicultural/bilingual resource navigation and support. With seed money in 2013, SEAMAAC piloted the Safe Families Program in the Burmese refugee community. SEAMAAC formed a Women’s Leadership Group consisting of Burmese refugee women who speak the Burmese, Karen, and Chin dialects. Seed money supported training and hiring a bilingual/bicultural Outreach Worker to provide outreach education, safety planning, case management, and resource navigation to survivors. SEAMAAC developed collaborative partnerships with domestic violence service providers, who provide training and technical assistance, as well as intensive legal and shelter support services. The model has proven successful, and has expanded into the Bhutanese, Chinese, and Indonesian communities. Safe Families has received recognition awards for advocacy on systems change, and for supporting Asian domestic violence survivors to develop leadership, self-determination, and resilience.

In early December 2016, SEAMAAC’s Health Programs Coordinator received an urgent phone call from a colleague at the Philadelphia’s Mayor’s Office on Immigrant and Multicultural Affairs. A Chinese immigrant woman in South Philadelphia had recently been released from the emergency room after sustaining serious injuries perpetrated by her husband, and was looking for help. That afternoon, a SEAMAAC Outreach Worker met with the woman. Over two hours, she shared through tears what had transpired over the past 24 hours, and talked about her immediate needs such as childcare, safety, and not knowing how she’d afford her rent as a new single parent. The Outreach Worker spoke this woman’s language and understood her culture. She provided support for her trauma, and helped her to see her strengths and resiliency. Together, they worked on safety planning and brainstormed solutions for her urgent needs. That was the first day of what would become a long partnership between this incredible survivor and SEAMAAC. Since that day, SEAMAAC staff have supported her to navigate court hearings and police and landlord interactions. She has connected with attorneys, housing resources, SNAP benefits, and therapists. She received behavioral health support for her children and childcare. She is working toward financial stability after starting her own business. She also started volunteering as a SEAMAAC “Peer Educator” where she supports other immigrants. She dreams of the day when she will no longer be fearful due to immigration concerns and has a thriving business that will enable her to give more back to her community.

Conclusion

As community-based organizations, AFAHO and SEAMAAC are committed to immigrant and refugee health access and culturally-informed models of care. This includes advocacy to support research and disaggregation of data instead of just using the inaccurate terms “Asian” and “Black.” This also means having honest conversations with our funders and community partners. AFAHO and SEAMAAC also are thinking strategically about being proactive about growing immigrant/refugee community health issues despite the anticipated cuts to federal, state, and city funding. For example, SEAMAAC is building a volunteer program in which families who have lived in South Philadelphia for a long time are matched with newly-resettled refugee families. The vision is for these neighbors to forge friendships, develop mutual understanding of each other’s cultures, and build a united community in South Philadelphia.

Whether called Outreach Workers, Case Managers, Community Health Workers, or Peer Navigators, successful programs require leadership from and compensation for bilingual/bicultural community leaders. Staff and community members are our strength and most important asset. They care deeply for their communities, and we support them in boundary setting, safety, and professional development to sustain them in this work. We value their time, skills, knowledge, and connections. SEAMAAC and AFAHO fundraise extensively to compensate them appropriately, and appreciate partnerships and funders who are also interested in investing long-term in this important role of bridge builder. As our target populations rely heavily on community leaders for information and resources, we want to create mutually benefiting relationships with community leaders to spread awareness and leverage support for our services.

Works Cited

Gozdziak EM. Training refugee mental health providers: Ethnography as a bride to multicultural practice. Human Organization. 2004; 63:203–210.

Ater, Richard. "Mental health issues of resettled refugees." Ethnomed. November 18, 1998.

Author Bios

Amy Jones is a licensed social worker who strongly believes in the connection of macro and clinical practice to larger social change movements. Her work in innovative program development and administration, and policy advocacy is fueled by working directly with people who seek help during challenging times in their lives. Their stories frequently highlight gaps in services and systemic barriers that need to be addressed. With the right support, they in turn can nurture others going through similar struggles. In her role at SEAMAAC, she directs the Health and Social Service Department including programs that are specialized in serving Asian immigrant and refugee communities in Philadelphia. Current program areas include health, senior services, safe families, post-resettlement refugee services, and civic engagement. Additionally, as a Therapist, she helps individuals, couples, and families from all backgrounds to accomplish their therapy goals at Northwestern Human Services (NHS) in the Mount Airy neighborhood of Philadelphia. Her primary clinical experience is in working with trauma survivors, those who struggle with anxiety, depression, grief and loss, building self-esteem, and those going through life transitions. She has prior work experience conducting community education and counseling around intimate partner violence at Women Against Abuse and the Lutheran Settlement House’s Bilingual Domestic Violence Program. Ms. Jones was recognized as a Champion of Change for the Affordable Care Act by the White House Initiative of Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Ms. Jones holds a bachelor’s degree in Social Work from Eastern University and a master’s in Social Work from the University of Pennsylvania. She is currently enrolled in a part-time post-graduate certification training in Marriage & Family Therapy at the Council for Relationships.

Christa Loffelman is a nonprofit consultant based in Philadelphia. She has a Masters Degree in Social Work from the University of Pennsylania, where she received the Ruth Smalley Award for her work on international social welfare issues. She is a licensed social worker in the State of Pennsylvania, and has 15 years of experience in working with immigrants, refugees, and other communities of color. Her expertise includes grantwriting, cultural competency, program development, intergenerational issues, urban social work, and nonprofit administration.

Oni Richards-Waritay currently serves as the Executive Director of the African Family Health Organization (AFAHO) where she is responsible for developing, implementing, and managing health and human service programs for the African and Caribbean immigrant and refugee communities in Greater Philadelphia, as well as directing the administrative functions of the organization. She brings more than eight years of public health program development and management experience to the position. Under her leadership, she has expanded AFAHO’s focus, increased its funding by nearly 150 percent and diversified its programs and services to respond to community needs. Oni previously served as a consultant in the Africa Program of the American Friends Service Committee where she organized advocacy activities related to health, social, and economic justice issues in Africa; with a particular focus on developing campaigns to impact U.S. congressional decisions on debt cancellation for African nations. She also spent time in Durban, South Africa creating programs and conducting fundraising activities for orphans impacted by the HIV/AIDS epidemic. She is currently in the process of expanding AFAHO to Tambacounda, Senegal to open a health and wellness center there. Oni was selected as a Visionary Emerging Leader by the Valentine Foundation and awarded a scholarship to attend the Non-Profit Executive Leadership Institute at Bryn Mawr College. She was also given the 2012 Echoes of Africa Community Service Award by the Mayor’s Commission on African and Caribbean Immigrant Affairs and a Citation by the City Council of Philadelphia for her work and dedication to the community she serves. In 2015 she also received the Community Leadership Award from ACANA for her efforts in addressing the health needs of the African Diaspora.