“Ultimately, a nonprofit sector that knows well how to collaborate will be far more effective in the pursuit of its public-spirited mission” (McLaughlin 1998a, xxiii).

Abstract

In June of 2008 two organizations that had served Philadelphia’s children for over 125 years each, merged to form a new nonprofit entity, Turning Points for Children. The two organizations, Philadelphia Society for Services to Children (PSSC) and Children’s Aid Society of Pennsylvania (CASPA), had been in discussion for two years before the merger was finalized. Four years after the merger, the new organization is stronger programmatically and financially, than the two independent organizations had been by themselves. More importantly, Turning Points for Children is now better positioned for continued growth with an ability to compete in the changing landscape created by Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services and its attempt to streamline case management and promote accountability among service providers.

A Culture of Merging

“What’s the problem? Why don’t we get everybody in the room and talk about opportunities and ways to collaborate?” Questions like these led to an event sponsored by Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services to promote collaboration. A lunch meeting was convened, organizations held discussions and then everyone went home and the subject was never brought up again. “That was my first lesson that this was a different world.”

Mike Vogel, CEO of Turning Points for Children, came to the nonprofit world after a 20-year career at Johnson and Johnson. He joined PSSC in 2000 as the Director of Operations and Programs. In 2004, he was appointed Executive Director and guided the PSSC through the merger process along with his counterpart, Gail Ober, Executive Director of the CASPA. While Mr. Vogel had no specific experience with mergers in the for-profit arena, he brought his corporate management experience to bear in navigating the nonprofit world and set about to look for a partner with whom to collaborate.

PSSC had previously attempted to merge with another nonprofit organization through a United Way grant. “I thought it was a great potential merger … This other organization didn’t have an endowment, and so had to be really good at raising their full budget every year, and I thought to myself, ‘that would be a great skill for us to add to what we were doing already,’ because we weren’t that good at it. I don’t think we even had a development person at the time.”

Negotiations eventually fell through, but by exploring the possibility of a merger, when the next opportunity came around, this time it was a successful. While PSSC and CASPA had no history of collaboration, Mr. Vogel’s predecessor, Helen Dennis, mentioned that she used to talk with Ms. Ober over lunch about merging, but that nothing more ever came of it. When Ms. Dennis retired and Mr. Vogel became CEO, he stated, “I don’t remember if it was her (Ms. Ober) calling me or me calling her,” but the discussions resumed and eventually turned into a serious effort focused on merging the two organizations.

In fact one of the main reasons that the Turning Points merger was successful was because both CEOs were involved in championing the merger. Early on they worked out how the management structure might look and what role each of them would play, according to their respective strengths. This alleviated two of the common road blocks to merging. According to Tom McLaughlin, Vice President for consulting services at the Nonprofit Finance Fund and nonprofit merger expert, ego and economics (the two big Es) can be strong factors in individual staff and board member motivations, and can lead to active or passive efforts to sabotage negotiations (McLaughlin 1998b). Because of the problem of conflicting motivations, organizations should use the absence of a CEO, for whatever reason, as an opportunity to explore merging (McLaughlin 2004).

According to Mr. Vogel, “On paper we looked like a merger that could happen in a week. We had similar missions; both our agencies were old; we both had money . . . There was a lot of synergy.” McLaughlin says that the entities involved tend to forget that mergers take time, and argues that mergers and affiliations need to be built into the culture of organizations because, “The integration process does take a long time. Therefore, you will be doing serial integrations if you are a large enough, complicated enough system. Ultimately, you will build it into your structure, into your staffing, and into your culture and you will get good at this,” (McLaughlin 2012).

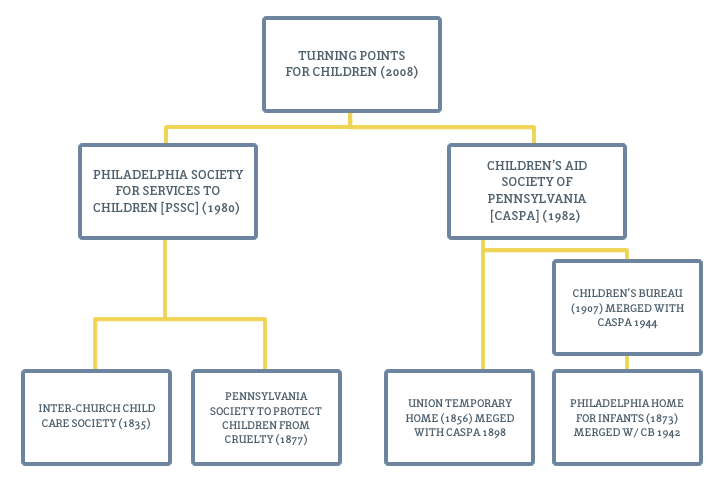

While Turning Points for Children is not yet a large enough organization to process serial mergers on the scale suggested by Mr. McLaughlin, it does have a long history of mergers and affiliations dating back to 1898. At least seven different organizations have become part of Turning Points’ pedigree (Figure 1). While neither PSSC nor CASPA has gone through a merger in the past 30 years, they are a part of the history of both organizations, along with their links to the nineteenth century. This shared identity helps the leaders of the two merging organizations recognize the other as kindred entities with which they can co-exist.

Philadelphia Society for Services to Children (PSSC) was formed in 1980 as a merger of the Inter-Church Child Care Society (founded 1835) and the Pennsylvania Society to Protect Children from Cruelty (PSPCC). PSPCC was chartered in 1877 and was the eighth such group in the United States at that time. The building at 415 South 15th Street, current home of Turning Points for Children, had acted as PSPCC’s headquarters from 1906 to 1980, when it became the headquarters for PSSC. The Inter-Church Child Care Society, formerly the Home Missionary Society, was founded in 1835 by members of the Methodist Episcopal Church as an evangelical group, which around 1854, “assumed the added task of placing poor dependent children in ‘good Christian homes’ in the country” (Clement 1979, 137).

CASPA was organized in 1882 and provided services for Philadelphia’s homeless and endangered children. During its long history CASPA had absorbed two other organizations: the Union Temporary Home for Children (merged 1898) and the Children’s Bureau (merged 1944). The Philadelphia Home for Infants (founded 1873) had previously merged with the Children’s Bureau in 1942.

The Children’s Bureau is an excellent example of the long history of collaboration among Philadelphia’s nonprofits. Established in 1907 through a joint effort of PSPCC, CASPA and The Adam and Maria Sarah Seybert Institution for Poor Boys and Girls of Philadelphia, the Children’s Bureau acted as a joint shelter for the founding agencies, as well as an information and education center for the more than sixty agencies in Philadelphia that received destitute children at that time (Gumbrecht 2003, 4). In 1908 a training program was developed to educate child-care social workers. This training program was the seed for what was to become the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Social Policy & Practice (Lloyd 2008, 4).

Figure 1: Organization Merger History