Article Summary

This paper provides an overview and analysis of the current transition of the child welfare system in the city of Philadelphia through the Department of Human Services (DHS). Only a few years ago was the city awakened to the ineffective state of the child welfare system, which led to mortal consequences and in turn incited a radical restructuring of the entire landscape of how at-risk families would receive services. DHS intends to enact this change through their Improving Outcomes for Children initiative and is appointing select organizations, which they call Community Umbrella Agencies, to become the single case management provider for a specific area of the city. This approach emphasizes the need to utilize the child’s natural community as the new system’s most potent tool and states that a community approach will increase provider accountability, decrease costs for services and improve the likelihood that children will achieve desired safety and permanency with their biological families where possible. Most importantly, it aims to ensure that no child will fall through the cracks of an ineffective system. Two organizations, the NorthEast Treatment Center and Wordsworth, are some of the CUA forerunners and have been laying the foundation for the eventual citywide transition. Their case studies, along with an analysis of the intended impact of the CUA model, provides us with insights into the future of the Philadelphia, and perhaps the national, child welfare system. A few other local CUAs are Catholic Social Services, APM and Turning Points.

Introduction

Child welfare is a field with no easy answers. The system is predicated upon the belief that if a family is unable to provide the necessary resources for the safety and well-being of its children, then that system will. Children from families on welfare, for the most part, have known mostly hardship; and historically, many of the traditional assistance methods employed by child welfare services involve taking the children out of their homes to live in group homes or with unknown families far from the familiar. Although the removal of children from their homes may be the key to their survival, it nevertheless is undoubtedly a traumatic experience for a little one still forming a basic understanding of life. Yet there is a new era of thinking within child welfare circles, one that abandons the traditional, institutional approach to services and embraces the belief that within the child’s own community is where the answers lie.

Philadelphia’s Department of Human Services Children and Youth Division

Social welfare concerns were at the forefront of public consciousness in the early 20th century. The City of Philadelphia established the Department of Public Welfare in 1919 and officially began to address child welfare issues a year later with the creation of a bureau dedicated to dependent children who were wards of the city. Today, this is the Department of Human Services Children and Youth Division. By the beginning of the 21st century, DHS was the largest child welfare agency in the state and had around 1,600 employees, serving thousands of children and families throughout the city (The Court of Common Pleas First Judicial District of Pennsylvania Criminal Trial Division [Misc. No. 0003211-2007], http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:http://www.phila.gov/districtattorney/pdfs/Grand_Jury_DHS_new.pdf). The child welfare system had come to function across multiple systems, creating a complex network of providers for the at-risk families of Philadelphia. The expansion of the agency was not unfounded: 1.5 million people reside within the county itself, and 25% of the population lives below the poverty line (Casey Family Programs, 2012). Undoubtedly, this context fosters the reality that many families are in need of services from an intensive child welfare system.

A portion of the DHS mission statement was to: “Protect children from abuse, neglect and delinquency; ensure their safety and permanency in nurturing home environments; and strengthen and preserve families by enhancing community-based prevention services.” (City of Philadelphia Department of Human Services, 2007). DHS organizationally went about fulfilling this mission using a dual-case management system. DHS itself assigned its own case workers to monitor and assist their families who were receiving services but also contracted with outside agencies to function as a “second tier” of assistance while bringing their own social and case workers into the equation. This meant that each child within the system had at least two individuals from two different agencies who intended to monitor their situations. If a family required more specialized care, such as mental health or substance abuse services, additional agencies were assigned to that family. One family could have more than six caseworkers coming in and out of their home on a weekly basis. Ultimately, however, it was DHS’ function to manage these contracted agencies to ensure that necessary communication and prevention measures were in place for each family.

Concerns about the effectiveness of DHS services were in question starting in the late 1980s, when several cases resulted in the death of a child (Court of Common Pleas MISC. NO. 0003211-2007, http://www.phila.gov/districtattorney/pdfs/Grand_Jury_DHS_new.pdf). Although DHS claimed to have made reforms within their working paradigm, it wasn’t until the death of Danieal Kelly in August 2006 that DHS was called on, by both the government and the public, to make radical reforms. Danieal and her family were officially registered with DHS and a contracted provider agency, yet her death was a result of severe neglect and starvation: she was found shut in a dark room and caked in her own filth. Due to her cerebral palsy, she was unable to move herself and it was concluded from the bedsores on her back that she had remained in the same position for weeks. However, the DHS files reported that she was visited on a biweekly basis by her DHS caseworker, as well as receiving regular visits from the provider agency, and these reports stated that Danieal was fine. In a child welfare system as established and expansive as DHS’ Children and Youth Division, it was baffling to imagine how this sort of oversight was possible.

The subsequent grand jury report revealed that there was nothing extraordinary about Danieal’s case on the outset that would have caused the child welfare system to fail to provide the needed services; the individuals assigned simply failed to do their jobs. The report concluded that the case revealed an “agency that is broken.” It called for major reform in accountability and transparency and for systemic change. The report stated that a mere revamping of policies or formal tools would not be sufficient for true transformation; the child welfare system had to put the children’s welfare before its own. In essence, the system had stopped placing children at the center of their decision-making. Something was severely wrong.

The grand jury was calling for a paradigm-shifting, disruptive reform to take place within DHS. The agency had been mired for so long in its own bureaucracy that previous attempts at reform had stymied. John F. Street, Esq., the Mayor of Philadelphia at this time, recognized the potential of the situation by responding to the outrage and mobilized the city to enact true change. Under his purview, the Philadelphia Child Welfare Review Panel was established to review and suggest needed reforms to the DHS system. The experts who comprised the panel were not fully associated with DHS, and ultimately they suggested 37 reforms, including: development of a safety assessment tool, expansion of team family decision-making meetings and development of a new mission statement and values centered on child safety. Street began to act on these suggestions as soon as they were delivered. One of his primary steps to reform, however, began with relieving the then-current DHS leadership team to begin anew.

Community Umbrella Agencies: A New Approach to Child Welfare in Philadelphia

Anne Marie Ambrose was appointed DHS Commissioner in 2008 at a time when Philadelphia was in need of major reforms to its child welfare system. Shortly after her appointment, the grand jury connected with Danieal Kelly’s death released recommendations that highlighted the dysfunction within DHS. Initially, Ambrose ensured that DHS implemented immediate, necessary changes within the existing child welfare system. However, for more than two years, Ambrose and her staff also explored child welfare models used in various other cities and states, including New York City, Florida and Kansas. At the same time, she engaged DHS leaders to better understand the existing system and their potential responsiveness to changes that might have been made (Casey Family Programs, 2012).

Philadelphia’s new solution to child welfare came with Improving Outcomes for Children (IOC). In 2010, Commissioner Ambrose presented this new model to the mayor’s designated Community Oversight Board and to leaders at the Department of Human Services. IOC refocuses the city’s commitment to improving the safety, permanency and well-being of children by creating a more strictly community- and family-centered child welfare system.

Various measures have proven the advantages of community-based models to child welfare. States such as Illinois, Florida and New York have used the Child & Adolescent Needs and Strengths (CANS) assessment, which measures the effect of partial or total changes to the child welfare system (The Praed Foundation, n.d.). This tool has also been used in Philadelphia to measure the adoption of a decision model for treatment foster care. It has not, in the past, been used to evaluate an entire system of services. The Quality Service Review (QSR) is another tool that has been used by states with community-based child welfare systems to measure outcomes. The QSR provides a frontline review of child welfare and education practices in a region or city at a specific point in time. It is currently being used in numerous states, including Pennsylvania as well as Illinois and Florida. Finally, the National Youth in Transition Database was created in October 2010 and became open for submissions in May 2011. Managed by the Administration for Children and Families (ACF), this database tracks the independent living services that US states provide to youth. It also tracks outcomes, allowing states to better track the performances of the independent living programs for their youth.

Among the various measurement tools that will be used under the IOC model, the CANS and the QSR in particular may serve as particularly useful measures of the new child welfare system. DHS plans to broaden its use of the CANS in order to evaluate all child welfare services. Likewise, the QSR will permit DHS to obtain ongoing, point-in-time data (Human Systems and Outcomes, Inc., 2010).

The IOC model came with a multiyear plan. A steering committee was created in late 2010, and by the middle of 2011 various working groups were actively meeting to negotiate and develop particular parts of the model. These working groups intentionally comprised leaders from a broad range of sectors affiliated with the child welfare system. Such sectors included DHS, social workers’ and supervisors’ unions, existing agency providers, community leaders and the mayor’s office.

The plan to transition to the new child welfare system under the IOC model was intentionally gradual. Though the initial rollout began in January 2013, full citywide implementation of this new system is not intended until 2016. In the meantime, certain parts of Philadelphia will still operate under the previous dual-case management model. Regardless, the short time frame under which the child welfare system has transitioned and continues to do so is notable.

IOC explicitly redefines and strongly restructures the roles of DHS and provider agencies. In recent years, the number of provider contracts with agencies had grown to over 250. Under the IOC model, the city is divided into ten regions based on city police precincts. A single lead provider agency will eventually be assigned to each region, resulting in ten provider agencies, known as Community Umbrella Agencies (CUAs), citywide. That provider agency may then subcontract with other agencies in its region for necessary services.

Additionally, professional roles within the child welfare system have changed under the IOC model. DHS retains responsibility for child investigations, intakes and referrals of families. DHS and the CUA work together in initially transitioning a family’s case from DHS to the CUA as well as in participating in future family team meetings and in engaging the community. However, the CUA notably assumes full case management responsibility. Families have a single caseworker who intensively coordinates services and serves as the family’s advocate (Casey Family Programs, 2012).

CUAs lie at the core of the IOC model. These community-based agencies are now primarily responsible for the case management provided to families requiring child welfare services in their region. Each CUA will be responsible for ensuring that the families who are referred to them by DHS receive comprehensive, local and accessible services. The first two CUAs were announced in 2012 and, one year later in early 2013, formally began receiving families from DHS.

The transition of services from DHS to CUAs is staged. It is broken up into four three-month phases over the course of one year. Within the first three months of rollout, a CUA receives in-home referrals from DHS. In the following three months, the agency begins to also receive regular foster care referrals. Between six and nine months into the rollout of the CUA, the agency begins to receive higher-level foster care cases, including families with behavioral health and medical needs. The final phase entails the CUA’s receiving congregate care cases from DHS. This segmented breakdown is meant to ensure that the CUA is fully prepared to provide sufficiently comprehensive, local and community-based services a referred family might require. From the beginning, selected CUAs have maintained a strong partnership with DHS. Through monthly meetings, these provider agencies and DHS work together to develop a community-based child welfare model tailored for Philadelphia.

Case Studies

The rollout of the CUAs began officially in January 2013 and will continue through 2016. As CUAs continue to be selected and established in Philadelphia, it is useful to examine two particular lead agencies that have already begun the implementation process. Case studies of the CUAs managed by NorthEast Treatment Centers (NET) and Wordsworth will specifically be explored.

NorthEast Treatment Centers: Implementing a CUA

Driving along Spring Garden Avenue east of I-95, it is difficult to miss the inviting mural that decorates the facade of NET’s administrative offices. “Perhaps the greatest social service…is to bring up a family,” the end of it reads, a quote from George Bernard Shaw. NET was one of the first provider agencies to receive a CUA contract from the city. However, its commitment to children and families in Philadelphia began decades ago.

NET is a multiservice agency. Founded in 1970, NET today provides behavioral health as well as social services to individuals and families at 15 sites in greater Philadelphia, the Lehigh Valle, and the state of Delaware. Currently with a budget of over $38 million annually, it has successfully expanded over the years on two fronts: NET offers multiple drug and alcohol services to adults through its behavioral health division. Through its children, youth, and family services Division, NET provides mental health services and child welfare services to families. It is here that in the last ten years, NET has grown significantly. NET has continued to broaden the services and programs it offers to families, even incorporating an in-home protective services (IHPS) program to better support families in need of child welfare services at the community level (http://netcenters.org/about/).

When discussions surrounding the IOC model and CUAs began in early 2010, members from NET were present. NET considers its goals to be fundamentally similar to those of DHS. Regan Kelly, who serves as Vice President of Children and Youth Services at NET, explains, “We’re not trying to change the system. We’re trying to connect the dots.” Formal agencies and informal, personal connections have existed in the communities where families live for years. Now it is the responsibility of the CUA to bring these resources together for a family.

NET has since been selected to serve CUA Region 1, which corresponds to the 25th police precinct. Comprising approximately 70,000 individuals, close to half of the population lives below the poverty line. The region is also diverse, with more than half of the population being Hispanic and one-third being African American. Many families are or have been connected to the child welfare system.

The city was deliberate in assigning regions with the greatest need for reformed services first to provider agencies. The 25th precinct was one of them, and NET was up to the challenge. (The other two were the 24th and 26th precincts, which were jointly assigned). Familiar with the families and resources of this part of Philadelphia, NET embraced its designation as a CUA when it was selected in March 2012.

In January 2013, NET commenced the rollout of its CUA after months of preparation. Communication with DHS after receiving its RFS was essential. “It really is a partnership,” says Kelly, and it is these conversations that are helping to shape the processes and procedures for CUAs still to be assigned. Organizationally, NET itself plans to fully transition its IHPS program to its CUAs. In the process, the CUA will ultimately become its own nonprofit 501(c)(3), independent of NET.

At the moment, however, the CUA remains in the early phases of its development. A facility at 5th Street and Cayuga Street will serve as a future community and administrative hub for the CUA. The facility will also act as a central location for CUA staff at NET. Currently, 25 NET case managers, five supervisors, and five community engagement staff and two DHS staff members have been assigned to this project. Critical for the staff right now is training. It is necessary for case managers and supervisors to reconstruct and expand their notions of case management. Under the previous system, case managers often had numerous short-term clients with numerous needs throughout Philadelphia. Now case managers are being pushed to think more long-term. Case management will indefinitely occur at NET and with NET and also with the family for the length of time that they require services.

Likewise, NET understands the need for community engagement and outreach is essential. “Kids want to be placed in their own communities in times of crisis,” Kelly said. Yet the resources must be there to support them. NET has begun by drawing on its existing partnerships in the community. Ties with agencies such as Congresso have been enormously helpful for NET as it manages early referrals. Additionally, NET has sought to develop new relationships in the community, with agencies such as the Lenfest Foundation. NET is continuing to connect the dots in its community, just as it always has.

Finally, NET recognizes that attention must be given to congregate care services, particularly for teens. Individuals may have concerns when accepting teens. As a result, many teens remain in congregate care for extended periods of time, costing the city greater amounts of money. CUAs may potentially help to alleviate this dilemma. If a teen’s local community is well understood by the CUA, it may be possible to find local resources, relatives or caregivers who could help. Taking a broad approach to family- and community-centered care has the potential to particularly benefit teens in Philadelphia. Moreover, reducing the use of high-end, congregate care services can allow for more money to be returned to communities.

Although NET only began receiving DHS referrals for Region 1 in January, a couple of lessons have already been learned. First, communication is key. Having a clear and strong partnership with DHS has smoothed NET’s transition to this new child welfare model and allowed it to maintain an active voice in CUA developments. Second, timelines do not always proceed as planned. Although a four-phase implementation plan seemed appropriate originally, it has proven to be limiting, with NET being unable to accept more complex cases. Finally, money and connections matter. Having financial security during the transition to a CUA has provided a source of stability. At the same time, NET recognizes that its partnerships in the community and elsewhere have been critical to its success.

The full implementation of NET’s CUA will take time. However, NET’s commitment to its families, the community and the objectives of IOC will likely support it through this process.

Wordsworth: Becoming a CUA

Wordsworth, a private, not-for-profit organization providing child welfare services for children, adolescents and families was selected to become the CUA for Region 5. Wordsworth’s history, mission and values are highly consistent with the goals and objectives of IOC. Wordsworth was founded in 1952 as a school to meet the needs of children with reading disabilities. During its 60-year history, the agency has continuously developed its array of services and its approach to treatment in response to the changing needs of its clients and an ever-evolving body of research and best practices.

Today, Wordsworth provides a full continuum of child welfare, behavioral health and specialized education services to close to 2,000 children, youth and families in the Philadelphia region. The agency uses an integrated understanding of each child/youth that views them within the context of their family and larger environment. The agency has prioritized the development and expansion of community-based programs that engage children, youth and families in their own homes and is committed to the belief that services are most effective, in both the short and long term, when they actively engage and collaborate with all systems that impact the child and family.

Wordsworth understands intimately the magnitude of working with complex, intensive cases and has the continuum of care and experience that made it an ideal candidate for a Community Umbrella Agency.

After a competitive RFP process, Wordsworth was selected as CUA Region 5 in May 2013. The CUA will go live in this region in April 2014. CUA Region 5 comprises the 35th and 39th police precincts within the city. Besides the predominant African American population, communities of Hispanic, Caucasian, Korean, Cambodian, Sub-Saharan African, Puerto Rican, and Vietnamese all live within these boundaries. Wordsworth felt that Region 5 was a good fit because the agency has a very strong set of services in these communities including in-home protective services and foster care and behavioral health services. In addition, 115 Wordsworth employees live in these neighborhoods, giving them a natural base for the community-based approach to the CUA.

Although Wordsworth already has a connection with the region and is well-versed in child welfare best practices, transitioning to the CUA model is no easy feat. It requires adaptation and creative thinking, both organizationally and programmatically, to ensure that the agency has the infrastructure in place to successfully implement the CUA. At this point, Wordsworth is in the early stages of strategizing for success—an implementation period, if you will. During this time, Wordsworth is working very closely with DHS to plan according to the organization’s and the region’s particular needs. Also, it is engaging in extensive outreach in the Region 5 neighborhoods to partner with local nonprofits for services and identify organizations and entities with which to collaborate once fully established in the spring of 2014. Wordsworth also has determined that it needs to hire and train more than 100 new staff in order to go live, a process that is now underway.

Organizationally, Wordsworth is securing space in Region 5 to house the CUA. This CUA location will operate as an additional Wordsworth site, along with its locations on Ford Road in the Wynnefield section of Philadelphia and Wordsworth Academy in Fort Washington. While this site will provide office space for the CUA staff, it is expected that services will be provided in the community rather than in the office. Wordsworth is also working to identify, subcontract with and manage services for DHS involved families in the neighborhoods of Region 5 including foster care and higher level child welfare services.

Programmatically, the seven programs within the Community-Based Services Department need to be aligned with the CUA model. For example, under the IOC, In Home Protective Services will ultimately go away, replaced by CUA In-Home Safety Services. Foster care will continue to exist as a distinct program at Wordsworth but will be closely aligned with the CUA. At the same time, Wordsworth will develop subcontract relationships for its own foster care program with other CUAs so that the agency’s resource homes can be available in their regions.

Wordsworth pursued this CUA position because the agency believes in the IOC model. With an extensive history of providing high-quality child welfare, behavioral health, prevention and specialized education services to children, youth and families in Region 5, Wordsworth is uniquely positioned to provide a full continuum of services to children and youth at risk of abuse, neglect and delinquency. The agency believes that its capacity, combined with the successful integration of community-based child welfare, behavioral health and prevention services, can play an essential role in achieving safety, permanency and well-being for the city’s children and youth.

Since Wordsworth’s selection as CUA Region 5 in May, DHS and the organization have remained in constant contact through strategic collaborative meetings and ongoing correspondence. They are paying careful attention to the infrastructure—making sure their new hires, their collaborating organizations and all of Wordsworth staff and constituents are on the same page and are ready to move forward in this new culture of child welfare in Philadelphia. Wordsworth is taking seriously the charge to become part of the fabric of the community and the importance of its role as one of the leading organizations adopting the CUA model.

Social Return on Investment

Measures used in other cities and states across the country have demonstrated the success of similar community-based models. As Philadelphia begins to roll out CUAs under the IOC model, it is important to understand the social value of the investment that is being made in them.

A Need for Change

The CUAs are changing the very structure of the child welfare system in Philadelphia. In doing so, they continue to be boldly disruptive. By contributing to the broad restructuring of DHS, the CUAs serve are reforming the hierarchy of a child welfare system that had struggled for decades.

There is a pressing need for the CUAs. As Regan Kelly notes, “We cannot go back to what used to be.” The CUAs are meant to be family- and community-centered organizations that are meant to support both greater well-being and greater permanency among children and youth in the child welfare system. Yet will that be the case? This form of child welfare system has only recently been rolled out in Philadelphia. However, one can gain a comparable social return on investment by examining data acquired from other states using similar models, in particular, the community-based care center in the state of Florida.

The scale of child welfare reform is broad. Under IOC, however, child well-being and permanency are two primary objectives. By focusing on these, it becomes easier to assess and evaluate this field. The CANS assessment offers a measurement of such factors from a strengths-based perspective. In the past, Philadelphia has used the CANS specifically to better understand residential lengths of stays for Treatment Foster Care. The use of this tool has not only helped the city to greatly reduce treatment foster care stays but also saved the city $11 million in just its first year of usage. Additionally, the CANS is used extensively in the state of Florida. It not only informs service delivery and tracks outcomes, it can also help to determine the appropriate level of care for a child. In particular, the CANS for children and adolescents in the child welfare system measures nine categories of information: functional status, caregiver needs and strengths, child safety, substance abuse, mental health, case management, child risk behaviors, criminal and delinquent behaviors and child strengths (Praed Foundation, 2012).

IOC Stakeholders

Many individuals and groups have a stake in this new child welfare system. Children and families are the primary target group of the CUAs. Families involved in child welfare seek to gain from services that are coordinated around their local communities. With the implementation of the CUAs, families stand to specifically benefit from shorter commutes to required services and a streamlining of case management services through one nearby provider agency.

Next, existing agency providers have enormous interest in the new system. More than 250 providers are currently in competition for the remaining CUA regional contracts. With such a limited number of contracts available under this new system, some agencies will lose out. Conversely, those agencies that do receive CUA RFPs will have to also adjust their previous policies and practices. Case managers in particular at these agencies will need to adapt to a more intensive, long-term and localized form of family case management.

DHS also has much at stake in the IOC model. Financially, DHS allocated a combined $25 million in the first year of work between APM and NET. While DHS continues to define to how much funding future agencies will receive, the department now must also carry the costs of running the existing child welfare systems simultaneously as well. Organizationally, DHS is taking a risk as well. Though it has been promised that no jobs will be lost during the rollout of the CUAs, this new system marks a fundamental, hierarchical change of power within DHS. Without case management responsibilities, DHS workers will need to adapt to new roles that focus more on intake, investigation and data tracking. Social workers’ and supervisors’ unions connected to DHS thus also have an interest in the success and returned value of this new child welfare system. Needing to protect their members both financially and professionally, these unions are highly invested in a smooth transition between systems.

Finally, the mayor’s office is also strongly invested in the success of the CUAs. It has contributed a great amount of money and research to this new approach. Though smaller improvements have been made in the DHS system in recent years, the mayor’s office has fully supported this overhaul.

Determining Inputs, Impacts and Social Return on Investment – A Florida Example

For the purpose of determining the true social return on investment, data drawn from community-based care centers in Florida in 2005 on out-of-home youth will be used as indicators to define inputs. Inputs reflect the quantified value of the sum of investments made by various stakeholders in a project. In this case, the inputs focus around those connected to the target group of the CUAs, namely, children and families in the child welfare system. In particular, inputs related to child permanency and well-being will be explored both through quantitative data and through data obtained from the CANS.

The state of Florida adopted a statewide community-based child welfare system in 1996. However, it was only in October 2006 that Florida obtained an IV-E waiver of the Social Security Act. In doing so, Florida was granted greater flexibility in using federal funding to promote services that supported well-being and permanency for children. In particular, the waiver was intended for three purposes. It was meant to reduce the number of children placed in out-of-home placements, to reduce the lengths of their stays and also to increase the amount of prevention and intervention services available in the state (Armstrong, Swanke, Strozier, Yampolskaya, & Sharrock, 2013).

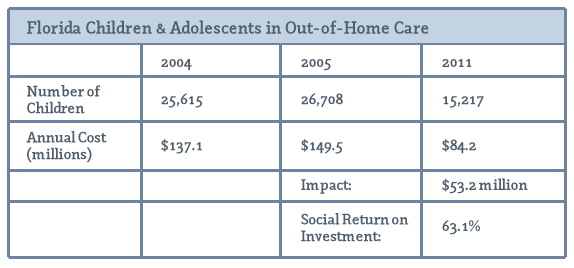

By the end of 2005, it is known that 28,679 children had entered out-of-home care placements in Florida. The yearly cost of keeping one child in foster care at that time was $5,214. Therefore, the state of Florida was investing $149 million dollars each year in placing children out of their homes and away from their families (Armstrong et al., 2013).

Several activities and events contributed to this cost. First, before the IV-E waiver, the state of Florida had extensively focused on community prevention, not on local reunification. Additionally, families also contributed to this cost. Many families frequently traveled great distances in order to reunite their families and to comply with the requirements mandated under the previous child welfare system. Attitudes and access changed once the IV-E waiver went into effect, however. After 2005, the state was not only able to focus more intensively on community engagement and prevention but also able to develop community and family programs to reduce the number of out-of-home placements. Families in the welfare system responded favorably to these new services.

The outputs from these expanded local services for families are evident. By the end of 2011, heightened community-based services and engagement had paid off. Out-of-home placements declined to 15,217 youth. The rates of out-of-home care declined because families were investing in family-centered resources in their communities. Meanwhile, the rate of reunification had increased from 50.5% in 2005 to 51.1% in 2011.

The outcomes associated with such improvements in community-based care are notable. By 2011, the annual cost of paying for youth in out-of-home care had declined to $84.2 million per year (Armstrong et al., 2013). Not only did the state gain from the expansion of community-based services, but families and children benefitted as well. Families were able to travel increasingly shorter distances for services, particularly regarding reunification procedures. They also had access to a growing amount of community preventative programming and resources. Finally, children were also able to gain from this improved system. Data from the CANS demonstrate improved capabilities among youth and their families.

The true impact of the community-based care centers in Florida affects how the final social return on investment is understood. The outcomes from these improvements following the IV-E waiver are striking. However, it is also likely that at least a portion of these outcomes would have been achieved even without the introduction of the waiver and the expansion of community-based services. Community-based care centers have produced generally positive results in Florida since their rollout in 1996. In 2004, 25,615 children were served by out-of-home care, resulting in over $137 million spent by the state. When this amount is subtracted from the over $84.2 million that state spent in 2011, the actual impact amounts to $53.2 million. This reflects how much money the state would have spent on out-of-home youth had it not been for the waiver (Armstrong et al., 2008).

The social return on investment for community-based centers in Florida incorporates this analysis of inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts. The objective of this community-based system is to increase permanency rates and to improve the well-being of children and youth in the system. More specifically, it seeks to reduce costs associated with out-of-home care. Social return on investment here can be calculated by dividing the total impact that this system will have by the total outcomes of the system in 2011. The final return on investment then comes out to be 63.1%.

The CUAs in Philadelphia have only recently begun to roll out. Nevertheless, it is important to understand the actual return that such a great investment might have for the city. The example of similar models being used in other states and cities allows for an adequate comparison. Community-based care centers in the state of Florida offer an ideal assessment by allowing the comparison of data before and after it expanded its community-based services. The high rate of social return on investment that is produced in this example offers favorable insight into what may similarly prevail in Philadelphia.

Moving Forward

Truly, there are no easy answers. Philadelphia’s child welfare system, by its own initiative, is in the process of fully transforming itself. This paradigm shift is leading the city into uncharted territory. However, DHS believes that through the lessons learned from the recent past, Philadelphia is equipped to not only handle but excel in this transition. Enacting cross-sector collaboration, increased accountability through single-case management, rigorous data tracking and intense focus on individual communities, Philadelphia intends to become one of the first successful implementers of this model as a nationwide leader.

At this point, there are many questions that have yet to be answered and that will have to remain unanswered until data and outcomes can act as a true compass. We can look to other examples and obtain a glimpse of the promise that this new model can hold. Despite the current ambiguity, in 2006 Philadelphia’s DHS was in dire need of a disruptive innovation in order to survive—it needed a lifesaver.

The concept of a community- and family-centered, single-case management system is an innovation for Philadelphia. Its theory and implementation represent a fundamental shift in the belief system landscape. It recognizes that the traditional paradigm was not achieving safe outcomes for at-risk youth and demonstrates the extent to which the city will go to protect the children that live within it. In 2006, during the grand jury trial of Danieal Kelly’s death, that dedication to children was in question. Through IOC and the implementation of the CUA model, DHS’ Children and Youth Division is reinforcing the belief that when families and communities are put at the very center of the decision, then Philadelphia can truly improve outcomes for children.

Sarah Evans is the associate director of Development at the Abramson Cancer Center at the University of Pennsylvania Health System and recently received her master of science in nonprofit leadership from the University of Pennsylvania.

Jennifer Lydic is a dual-degree graduate school candidate at the University of Pennsylvania, where she is pursuing a master of public administration at the Fels Institute of Government and has recently completed a master of social work from the School of Social Policy and Practice.

REFERENCES

Armstrong, M. I., Swanke, J. R., Strozier, A., Yampolskaya, S., & Sharrock, P. J. (2013). Recent changes in the child welfare system: One state's experience. Children and Youth Services Review, 35(10), 1712–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.07.005.

Armstrong, M., Vargo, A., Jordan, N., King-Miller, T., Sowell, C., & Yampolskaya, S. (2008). Report to the Legislature: Evaluation of the Department of Children and Families Community-Based Care Initiative, University of South Florida. Retrieved from http://cfs.cbcs.usf.edu/_docs/news/CBC_LegReport.pdf

Casey Family Programs. (2012). Improving outcomes for children in Philadelphia: One family, one plan, one case manager. Philadelphia, PA: Casey Family Programs. Retrieved from http://dynamicsights.com/dhs/ioc/files/1330_SC%20IOC%20Philly%20Chronicle_sm.pdf

City of Philadelphia Department of Human Services. (2007). Department of Human Services at a glance 2007. Retrieved from http://www.phila.gov/districtattorney/pdfs/Grand_Jury_DHS_new.pdf

Human Systems and Outcomes, Inc. (2010). Pennsylvania Quality Service Review (QSR) for children, youth and families. Retrieved from http://www.pacwrc.pitt.edu/Resources/PA%20QSR%20Protocol%20Version% 201%200.pdf

The Praed Foundation. (n.d.). About the CANS. Retrieved from http://www.praedfoundation.org/About%20the%20CANS.html#Here