By José Rodrigues Freire Filho, José Francisco García Gutiérrez, Silvia Helena De Bortoli Cassiani & Fernando Antonio Menezes da Silva

Background

In recent years, Interprofessional Education (IPE) has been introduced into policies on human resources for health (HRH) in the countries of the Region of the Americas, predominately in the United States and Canada, but also in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). The Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO) has encouraged its member states to adopt this approach and support policymakers in expanding its use. PAHO’s Strategy on Human Resources for Universal Access to Health and Universal Health Coverage and its Plan of Action 2018-2023 encourages countries to promote the development of interprofessional teams in integrated health services networks using IPE, diversifying learning settings, and promoting collaborative practice. Objective: To present an overview of national IPE plans developed with PAHO/WHO support in 19 countries of LAC during 2017-2019. Method: In 2017, PAHO's Human Resources for Health Unit launched a technical cooperation strategy to support countries of the Region of the Americas in implementing IPE in their HRH policies. The strategy was mainly focused on networking, research, sharing of experiences, and activities such as international meetings, webinars, guidelines, publications, and virtual courses. Results: The Regional Network for IPE in the Americas (REIP) has been established (educacioninterprofesional.org) and 19 countries have submitted national action plans for the implementation of IPE. Overall outcomes derived from the evaluation of those plans will be presented using four dimensions: 1) Dissemination and research; 2) Faculty recruitment and development; 3) Legislation mechanisms; and 4) IPE in permanent education programs. Conclusion: International organizations have an important role to play in articulating and collaborating with countries to incorporate innovative approaches, such as IPE and interprofessional collaborative practice (ICP), directed to transforming and scaling-up health professions education towards the achievement of universal health, and to ensuring its alignment with health services demands and population needs.

Introduction

Since 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) has promoted interprofessional education (IPE) and interprofessional collaborative practice (ICP) as innovative strategies that hold promise in mitigating the global health workforce crisis (WHO 2010, 7-10).

WHO recognizes IPE “when students from two or more professions learn from each other to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes,” and ICP "when different professional backgrounds work together with patients, families, caregivers, and communities to offer the highest quality of care” (WHO 2010, 7-10).

In recent years, IPE has been introduced into policies on human resources for health (HRH) in the countries of the Region of the Americas, especially in the United States and Canada, but also in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) has supported its member states in adopting this approach and encouraged policymakers in expanding its use (Silva, Cassiani and Freire Filho 2018, 26). In addition, PAHO’s Strategy on Human Resources for Universal Access to Health and Universal Health Coverage and its Plan of Action 2018-2023 endorses the development of interprofessional teams in integrated health services networks using IPE (PAHO 2017, 2-3).

In this regard, IPE is necessary to prepare the health workforce to engage in collaborative efforts; to respond to local health needs in a dynamic environment; to improve human resources for health capacities and outcomes; and to strengthen health systems and services. A high level of synergy between health workforce planning and health education systems is required to facilitate the advancement and sustainability of IPE and ICP (CAIPE 2002, CIHC 2010, IPEC 2016, WHO 2010).

The aim of this article is to present an overview of the development process of national IPE plans in 19 countries of LAC -- with PAHO/WHO technical cooperation -- during the period 2017-2019, as an innovative contribution for the transformation of health professions education in the Region of the Americas.

Methods

The basis for this study was developed through three annual regional IPE meetings (in 2016, 2017, and 2018) and the establishment of the Regional Network for Interprofessional Education in the Americas (REIP).

Bogota Meeting 2016

In 2016, PAHO/WHO held a regional meeting in Bogota, Colombia that aimed to support countries in the Region in the implementation of IPE and IPC. Participants included representatives from ministries of health and education, academic institutions, schools, and professional associations from 12 countries. They discussed the theoretical, practical, and political rationale for IPE, as well as the individual and institutional attributes, resources, and commitments required for its implementation (PAHO 2017).

Brasilia Meeting 2017

On December 2017, a second regional technical meeting on IPE was held in Brasilia, Brazil. The event, organized jointly with the Ministry of Health of Brazil, was attended by representatives from 22 countries of the Region of the Americas. The purpose of the meeting was to discuss processes for incorporating IPE into policies on human resources for health, to establish a common agenda for strengthening IPE in the Region, and to foster the preparation of national action plans to implement this approach (PAHO 2018).

During this meeting the Regional Network for Interprofessional Education in the Americas (REIP) -- coordinated by the Ministries of Health of Argentina, Brazil, and Chile -- was formally established and its directives approved in accordance with the principles and lines of action set forth by PAHO’s Strategy on Human Resources for Universal Health (PAHO 2018).

Buenos Aires Meeting 2018

On December 2018, the City of Buenos Aires hosted the Third Technical Meeting on IPE sponsored by PAHO. The meeting was attended by representatives from 15 countries of the Americas that confirmed their commitment to invest in IPE and shared the results of ongoing activities of their national plans (i.e., mapping of IPE experiences, research studies, workshops, and conferences) as members of REIP (educacioninterprofesional.org),

The REIP constitutes a technical cooperation strategy for promoting IPE and ICP with a view to improving the quality of health services and enhancing the education of health personnel through interprofessional teams (REIP 2018).

This network supports countries, in collaboration with PAHO, to develop action plans for implementing IPE through intersectoral collaboration between ministries of health and education, academic institutions, and professional associations. It also serves as a platform to exchange and disseminate IPE information, experiences, and scientific evidence; identify common IPE facilitators and barriers; encourage the development of multicenter research; and monitor and support country activities (REIP 2018).

In coming years, REIP hopes to maintain its support for the development of leadership in IPE, increase the number of member countries of the network, and remain affiliated with the main institutions and global bodies working on this topic (REIP 2018).

Results

Using the Regional Network for IPE in the Americas (REIP) (educacioninterprofesional.org), 19 countries of LAC have submitted national action plans for the implementation of IPE.

Figure 1: Countries of LAC and Caribbean with IPE plans (REIP 2018).

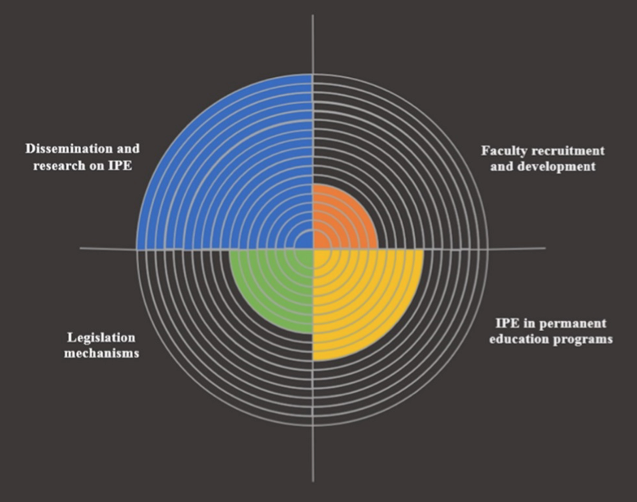

These plans have been analyzed using four dimensions: 1) dissemination and research on IPE; 2) faculty recruitment and development; 3) legislation mechanisms; and 4) IPE in permanent education programs.

1) Dissemination and Research on IPE

The first dimension refers to the activities foreseen in the IPE plans of the countries related to the promotion of events, such as meetings, conferences, conducting studies to address the concepts of IPE, its theoretical and methodological basis, and the recognition of its power for the transformation of education health professions. In a survey conducted by PAHO/WHO, several countries in the Americas are unaware of the concept of IPE, as well as its applicability. All 19 countries present IPE dissemination and research activities in their plans.

Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, Chile, and Colombia discuss the importance of creating evidence on IPE. Paraguay, Uruguay, Colombia, and Costa Rica are conducting surveys on the subject at the national level. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, El Salvador, Panama, Uruguay, and Cuba held events on IPE to disseminate the theme in the countries.

2) Faculty Recruitment and Development

Faculty recruitment and development is a key factor for the implementation of IPE. This refers to the activities that prepare and assist faculty in all educational settings (classroom, clinic, hospital, and community). The initiatives proposed by the countries in this dimension are the development of courses for leaders in IPE who have the knowledge, skills, and attitudes to teach both students and colleagues to work collaboratively.

For IPE faculty development only six countries presented actions in their plans: Bolivia, Brazil, Costa Rica, Honduras, Panamá, and Uruguay.

Brazil held a virtual course in IPE faculty development on July 2018. The IPE course was attended by 300 professors, directors of graduate programs on the health of the country, as well as professionals who work to accompany students in health services (REIP 2018).

3) Legislation Mechanisms

Legislation is fundamental to the effectiveness of IPE and institutionalizes a country's commitment to the implementation of IPE. With this impetus, many countries are in the process of developing and strengthening their legislation for IPE and are embracing effective mechanisms for its incorporation into HRH policies.

In the countries' IPE plans, examples of regulatory mechanisms are the formulation of guidelines, protocols, resolutions, creation of national IPE networks, and other resources that assist in the implementation of IPE.

For the IPE legislation mechanisms, eight countries included activities in this dimension in their plans. Some countries, such as the Dominican Republic and Suriname, are proposing the establishment of National IPE Networks and Brazil and Panama have the proposal to formulate resolutions on IPE to promote changes in the model of the training of health professionals and to include the IPE in curricula.

4) IPE in Permanent Education Programs

Courses, seminars, and any other educational activity directed to health professionals, aiming to develop skills or knowledge applicable to practice, are considered permanent education programs. With respect to IPE in permanent education programs, 11 countries have activities in their plans, among them Guatemala, Nicaragua, Panama, and Venezuela have presented strategies for the qualification of health service professionals, making use of the theoretical and methodological basis of IPE.

Figure 2: Activities of countries' IPE plans according to the dimensions of analysis.

Conclusions

This study showcases ongoing experiences in implementing IPE and ICP as part of HRH policies in the LAC Region. It also stresses the important role that international organizations (such as PAHO/WHO) could play in encouraging countries to incorporate innovative approaches directed to transforming and scaling-up health professions education aligned with health services demands and population needs.

Achieving Universal Health means that everyone, irrespective of their socio-economic background, ethnicity, gender, or race, is covered by a well-financed, well-organized health system offering quality and comprehensive health services, be they curative, preventive, rehabilitative, or palliative. Interprofessional health teams and collaborative practice may contribute to the removal of barriers to the access of health services -- either physical, geographic, cultural, or economic. However, neither IPE and ICP, nor the creation of interprofessional health teams, are ends onto themselves. They are means to increase access to equitable, quality health services, and improving the organization of health systems and the working conditions of the people who work in them.

IPE networks could serve to promote innovation in health and education, but they imply changes in the way professional competencies are taught, regulated, exercised, and shared. For this reason, PAHO/WHO shall continue supporting member states and educational institutions in the Region:

- To continue carrying out the series of seminars on the IPE and ICP, maintain the IPE virtual course in the Virtual Campus of Public Health, and launch a new course for the IPE faculty development.

- To incorporate IPE and ICP both in educational academic programs and HRH policies as key strategies to increase access to health and to improve care quality.

- To introduce specific IPE standards and indicators as part of the accreditation processes of health professional’s education and programs, as a major driver to promote change.

- To develop interprofessional teams at the first level of care with combined competencies in comprehensive care, intercultural skills, and social determinants to health. The target would be to have 30 countries with interprofessional health teams at the first level of care, consistent with the model of care, by the year 2023.

Works Cited

Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC) Competencies Working Group. 2010. A National Interprofessional Competency Framework. Vancouver, BC: Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. Retrieved from www.cihc.ca/files/

Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education (CAIPE). 2002. Interprofessional Education - a definition. Retrieved from: www.caipe.org.uk/about-us/defining-ipe

Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC). 2016. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

Pan American Health Organization. 2017. “PAHO cooperates with countries of the Region to incorporate interprofessional education into health education policies.” Privacy & Terms. Las modified December 17, 2017. www.paho.org/hq/

Pan American Health Organization. 2017. Interprofessional Education in Health Care: Improving Human Resource Capacity to Achieve Universal Health. Report of the Meeting. Bogota, Colombia, 7-9 December 2016. Retrieved from: iris.paho.org/xmlui/handle/

Pan American Health Organization. 2017. Strategy on human resources for universal access to health and universal health coverage. [29th Pan American Sanitary Conference, 25-29 September 2017 (document CSP29.R15). [Retrieved from: www.paho.org/hq/

Regional Network for Interprofessional Education in the Américas (REIP). Privacy & Terms. https://www.educacioninterprofesional.org

Silva, F. A. M. D., Cassiani, S. H. D. B., & Freire Filho, J. R. (2018). Interprofessional Health Education in the Region of the Americas. Revista latino-americana de enfermagem, 26. Retrieved from: www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v26/

World Health Organization. 2010. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice (No. WHO/HRH/HPN/10.3). Geneva: World Health Organization. Retrieved from: apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/

Author Bios

José Rodrigues Freire Filho is an International Consultant on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice in the Department of Health Systems and Services (HSS) at the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). He is responsible for the implementation of interprofessional education and collaborative practice in health and provides technical assistance to countries in the Region of the Americas. He is a Pharmacist with a PhD in Interprofessional Education.

José Francisco García Gutiérrez is a Regional Advisor on Human Resources for Health Development in the Department of Health Systems and Services (HSS) at the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). He holds a PhD in Public health and his work focuses primarily on social accountability in health.

Silvia Helena De Bortoli Cassiani is Regional Advisor for Nursing and Allied Health Technicians in the Department of Health Systems and Services (HSS) at the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). She holds a PhD in Nursing and provides technically cooperation to Member States to advance nursing through education, research, and broadening the scope of nursing practice in Primary Health Care.

Fernando Antonio Menezes da Silva is Unit Chief in the Unit of Human Resources for Health (HSS/HR) in the Department of Health Systems and Services (HSS) at the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). He holds both a MD and PhD in research and completed a fellowship and post-doctorate in Evaluation of Higher Education. He has extensive experience in management of human resources for health and health systems strengthening.