The Gulf of Mexico disasters of 2005, replayed in 2010 in man-made form, brought into sharp focus and stark relief, for the entire world, the widening chasm between the “haves” and “have-nots” in the US. In American poet laureate Dana Gioia's classic essay on why the situation of poetry is of consequence to the entire intellectual community, he wrote, “A society whose intellectual leaders lose the skill to shape, appreciate, and understand the power of language will become the slaves of those who retain it—be they politicians, preachers, copywriters, or newscasters” (Gioia 2002, 17). As public health scholars and practitioners, our commitment to social justice, equality of opportunity, health enhancement and disparities elimination, locally and globally, infuses our work, and, for many, our activities during our discretionary time as well. Melding of messages delivered through scientific endeavor and poetic reflection may serve to inspire, direct and catalyze the social change needed to make progress toward these lofty, and attainable, goals and aspirations, to manifest then-Senator Barack Obama’s fiery declaration in his 2004 Democratic Convention address of the “audacity of hope.” As a capella women's music group Sweet Honey in the Rock asserts in Ella’s Song, “We who believe in freedom cannot rest….”

As public health professionals, we place disproportionate emphasis on the science driving the development of health interventions, and devote insufficient attention to the science of disseminating that knowledge to increase individual and societal adherence to healthy practices. Furthermore, most health decisions are emotionally and socially, versus intellectually or cognitively, driven! As resources inexorably constrict and need relentlessly grows, we must increase our efficiency by living our professional convictions—socially, economically, politically and spiritually, through the “scholarship” of engagement. As Gandhi asserted, “we must be the change we wish to see in the world.” And we must marshal all of our talents, forces and resources, the seen and the “unseen.”

My poetry, a mix of self-discovery, social commentary and health advocacy, with frequent use of sports as a metaphor, sometimes veers toward the political. But, of course, as a physician for over a quarter-century—of populations now, not individuals—health broadly defined (physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, financial) surfaces in most of my work. And basketball has become a coda for identification with black culture, as its visible and exquisite manifestation of excellence, assertion of dominance and channeling of anger and frustration symbolizes our hopes and dreams as a people. Especially at the intersection of race and gender, as in We, Too, Are Ballas.

...thriving, striving and deriving

the last ounce of energy, determination

frustration at any limitation!

Engendering fearlessness

in other arenas,

in which ovaries

give us competitive advantages

over cojones.

During the run-up to the 2008 election, President Barack Obama used his love of basketball to signal his blackness when some African Americans questioned his identity or cultural grounding. Basketball also supplies the “props”—assertion of insider status—to criticize our own. Like the all-too-common sexual risk-taking and early childbearing among young black people that bubbled up in B-Ball Blues.

…These ballin' brothas

Many, not all

Plantin' babies

'Thout committin'

To the sistuhs

Carryin' 'em...

Non-men

Disingenuous boys

Don't they know

That the anger

Of those sistuhs

Toward them

Will be visited

Upon their sons

These ballin' brothas

Many, not all

With so much talent

Drive, discipline

And sheer power

Caught up in toys--

Rides, Cribs,

Threads,

Boxes

Rather than politics,

Literature, spirituality,

Education, health

NBA is mo' letters

'N most of 'em

Can handle

At one time...

These ballin' brothas

Some, a few

Are men...

Who should be celebrated

With Martin, Malcolm and Marcus…

Not so much

For this career

As for that

Which is sure

To follow

I’d like to advance my 7 A’s of Constructive Public Health Action, against chronic disease, violence, social injustice and the many other threats to the health of our communities.

1. Activism

No, it didn’t go out in the ‘60s. We need it as a way of channeling our righteous anger and frustration at a sociopolitical system hostile to the empowerment of women, older people, younger people, people of color, people who aren’t affluent or Christian or heterosexual, people who didn’t go to the “right” schools or don’t live in the “right” neighborhoods. Rather than at ourselves through violence, substance use, depression, sexual risk-taking and ill-prepared childbearing. Let me emphasize that activism takes individual (e.g., letter-writing) and collective (e.g., organized protest) forms, creating moral and political imperatives. Finally, the Occupy movement in its outrage at escalating social inequality is matching the energy of the Tea Party!

My activism these days generally takes the form of intellectually challenging the status quo. In many instances, it’s no more than figuring out ways to scientifically document common sense observations that most people who inhabit non-affluent communities make daily. For example, we published a study several years ago examining the contribution of commercial advertising to obesity-related disparities and found, to no one’s surprise, that schools and day care centers in low-income zip codes have many more ads for sugary beverages and fast food than those in wealthier zip codes (Hillier et al. 2009; Yancey et al. 2009). We also found similar distributions of ads for sedentary products and services, e.g., TV shows, films and cars. And ads promoting physical activity were nearly non-existent in any area. There were so few ads in affluent white communities that we had difficulty finding a zip code for inclusion. In a similarly conceived project, we quantified the amount of moderate to vigorous physical activity that kids get at school during PE—on average, 6-8 minutes during a 30-minute class and even less in low-resource schools (UCLA 2007). For Lettin' Me Play arises from my gratitude to those who opened the doors and provided the guidance, allowing me to "get in the game" of academic public health practice.

Mos' times

They don' even let us

Get in the game

Don' let us

Showcase our wares

Tell us

We're weak

Crush

Our spirits

Deny

Our feistiness

Subjugate

Our vision

Scrutinize

Our style

Criticize

Our every move

Relegate us

To the sidelines

To cheer on

The action

Under the guise of

Protectin' us

Can't run

'Less we get in the game

Can't score

'F we don' get the ball

Y'all made sure

That didn' happen

To me

2. Sociopolitical and Historical Awareness

People who do not understand the historical context of their current standing suffer their ignorance in lost collective self-esteem and pride in accomplishment. All of the great leaders of our communities, such as Susan B. Anthony, Angela Davis, Eleanor Roosevelt, Shirley Chisholm, Indira Gandhi and Barbara Jordan, have tried to address and influence our hedonism, materialism, consumerism, identification with the aggressor, competitive “crabs in a bucket” mentality and other destructive values we’ve foolishly embraced. Suffice it to say that people who don’t know their history are destined to repeat its mistakes. Ain' Like There's Hunger speaks to many of these issues through the lens of the sociodemographic and environmental conditions underlying obesity disparities (Yancey 2007; Yancey et al. 2006; Yancey & Kumanyika 2007).

Sweet tooth

Salt tooth

Chocolate tooth

Jonesin’ for fries,

Triple deck Mac,

Coke and pork rinds

But no walkin’ tooth

Swimmin’ tooth...

Weight liftin’ tooth

After all,

Ain’ like there’s hunger…

Mind numbin’ early gig

Second gig even worse

Kids in between

Gotta be fed

Read to

Homework checked

Ears inspected

Dark park?

Cold out?

After all,

Ain’ like there’s hunger…

Sittin’ all day

Tryin’ to look nice

’Do costin’ thirty, fo’ty

Dollas a week

Heels and huggin’ skirt

And these fifty extra pounds

I’m carryin’ around

Stairs ’re a joke!

Walkin’ at lunch?

Humidity wreck my hair

After all,

Ain’ like there’s hunger…

So if bein’ a nation

Of couch potatoes

Or “mouse” potatoes

Is really that bad

Why don’t they

Make it easy?

Perk me up

Since I’m usually down

Where I work

On the “company’s” clock

Yeah, how ‘bout a little recess?

Like when we were

Kids in school

I might take a stroll

On “their” time!

Or find some jammin’ tunes

For my little group

Packin’ some

extra pounds

Been awhile since we got down!

“Shiftin’ & movin’ &

swingin’ & groovin’”

Get that natural high flowin’

Now that might make me hungry

For more!

3. Advocacy

We all have some knowledge or power in some arena that can help somebody in need to help themselves, be it a relative, friend, patient, co-worker, neighbor or somebody we just run into in the grocery store. I somehow survived the most challenging advocacy project of my life—navigating the health care and social services bureaucracies to manage my mom’s last decade of life. I wrote She Went Away out of the anguish of protracted loss imposed by Alzheimer’s, and in celebration of a life well-lived.

Alzheimer’s

Steals

Robs

Takes

Drains

Eradicates

Insidiously

Assiduously

Unrelentingly

A knowing smile

An arched eyebrow

A “stop you in your tracks” stare

A hearty laugh

A nervous glance

A sarcastic chuckle

A made-up word

Good glugallywogallywomblebot!

1% here

2% there

She

Slipped out

Seeped through

Was spirited away

Like sweat through her pores

Like tears through her eyelashes

Like blood from her veins

Like milk from her breasts

Like saliva from her lips…

The memories

Of a life well lived

The pride

Of a life much appreciated

The confidence

Of a life much heralded

The dreams

Of a life lived vibrantly…

But not

The love

Of a life well connected

The presence

Of a life lived reverently

The hopes

Of a life well anchored

The satisfaction

Of a life lived appreciatively…

At what point

Has the person

Seeped out

Slipped through…

The cracks

The fissures

The crevices

The quakes

The fault lines…

At what point

Is the person

No longer there?

Behind the façade

Of the vacant stare

The hollow laugh

The angry countenance

The desperate clinging

The empty smile

The desolate look

The crumbling features

The reedy voice

A Hollywood set

Windows without sashes

Streets without gutters

Lawns without sprinklers

Chimneys without flues

Rain without clouds

Snow without frost

Grass without dew

Houses without foundations

When is a life

No longer worth living?

On some level

She knew

And she left

And she spared me

An Alzheimer’s death

4. Physical Activity

Sedentariness, suboptimal nutrition, smoking and other substance misuse, and high-risk sexual activity account for most chronic disease risk and disparities, including the high blood pressure and diabetes leading to most of the need for organ transplantation. And there is a "multiplier effect" of preventive practices by health care providers and other opinion leaders and gatekeepers. Recapturing Recess corrals a bit of the energy and exuberance we've lost touch with, helping to frame physical activity as something people want, not just something we think they need, as our studies of Instant Recess® demonstrate (Yancey 2010; Barr-Anderson et al. 2011; Maxwell et al. 2011; Whitt-Glover et al. 2011).

Now I know

Y'all can remember

The recess bell

The wave of exhilaration

The sigh of relief

The sheer release

The transformation

Of fidgeting

Into linear motion

Raise up your hands

If you can remember

All that pent-up energy

Exploding

Into air and space

Leaping

Into wind and sunshine

Launching

Onto grass and hardwood

Soaring

Into goals and hoops

And if you can recapture

Even a little of the joy

Of unbridled movement

Then just maybe there’s hope

For the couch potatoes!

Those of you too worn down even to fidget!...

5. Spiritual Attunement

Spirituality has offered respite and rejuvenation throughout the millennia in the struggle against oppression and inequity. Speaking Truth to Power testifies to my core beliefs, with a nod of support to Anita Hill, as it was written during the Clarence Thomas confirmation hearings.

Thanks, Cornel

And Samuel...

And Daddy

For remindin' me

That love's

What it's all about...

I can't win at hate

'Cause the devil's

Too fickle a master

Got no integrity

'S soon stab you in the back

'S look ya in the eye

I'm on God's side

I was born in faith

My folks'

And my people's

And in faith

I shall live or die

But not waver

I shall speak truth to power

With love

Stan' for somethin'

Not fall for nothin'

Truly live

And when I become

Too much of a threat

Fall for somethin'

Because this mortal life

Is such a small part

Of our eternity

And recognizing only

One Higher Authority

Makes life so much simpler

And more easily relinquished

6. Altruism

A reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer introduced his article about a local drive to recruit bone marrow donors a few days before Christmas in 1992, (Kanaley 1992) writing, “As the line of children snaked toward Santa, and city shoppers shouldered their way between chain stores, an occasional hero slipped into a white tent in the Gallery yesterday to get stuck with a needle and have a teaspoon of blood drawn. ‘Do I get paid for that?’ inquired Tyrone Lucas, 19, of South Philadelphia, as he hesitated at the entrance of the tent set up by the city health department. The answer was no. But Lucas went in anyway. ‘It was all right,’ he said a few minutes later. ‘I feel good to be into something.’" I’ve heard people who actually donated marrow say that the “high” lasted a year or two. This speaks to the connectedness that we need for grounding and well-being. And that brings me to a poem near and dear to my heart that speaks to the research interest that brought me into public health, namely role modeling. In order to move our lives in the direction we envision, we need to exchange a lot of Currency, beyond just the flow of dollars.

I gave Akil

The spot I earned

In a pick-up game

You know, b-ball

To a kid

That's like money

Currency

... I gave Robyn

A heartfelt compliment

Told her

She's the best

Student I've known

To a kid

That's like money

Currency

Akil gave me

An ego boost

Told some other folk

I taught him to play

You know, b-ball

To me

That's like money

Currency

Robyn gave me

The ultimate gift

Told my aunts

She wanted to be

A model/doctor

Just like "Aunt Toni"

To me

That's like money

Currency

All that currency

Exchanged between us

And nobody

Spent a dime!

That poem was inspired by a particular pick-up basketball game in a park here 10 years ago that I sat out while my godson played in my place. It was a bit like watching the Michael Jordan of the ‘90s raise his game at will in the last few minutes of a tight contest, which reminds me of the incredible empowerment associated with a powerful mentor communicating a belief in you. Sometimes that empowerment occurs through no personal communication at all, but by our choice of a powerful other as a role model, most often with whom we share sociodemographic similarities, like gender and ethnicity. We've been able to demonstrate this positive association between role modeling and healthy outcomes in studies of Los Angeles County and California adolescents (Yancey et al. 2002; Mistry et al. 2009; Yancey et al. 2011). I believe that the provision of a diversity of images of powerful others, self-efficacious others, is critical in addressing racial/ethnic health disparities.

7. Authenticity

To understand who we are, we must understand our past, not only individually, but collectively—our “ancestral capital.” Is a poetic voice hereditary? Perhaps the facility with language, agility of intellect, reality of memory, and lability of mood are. But the talent’s the small part of the poetic spirit. The drive, determination, dedication and discipline to seek our mission, follow our passion, and live our prayer are wholly a function of the role models and mentors whose paths we cross or who cross ours.

My aunt, Antronette (Toni) Hall Brown, was one of my first role models, and my mother named me after her. She earned her B.A. in English from the University of Kansas in 1938 and her M.Ed. from Columbia University in 1956, after 6 summers of commuting to New York from Kansas City by car. She was a pioneer in the development of adult basic education in promoting literacy. She wrote “A Perfect Day” as a college freshman, and it was published in the newspaper of her former Kansas City, KS high school 75 years ago. She died five years ago at age 90, but her spirit lives on and her work is carried on by the minions of us she inspired. She, indeed, lived…

A Perfect Day

God, give me strength to face this

day

The obstacles that block my way,

Take Thou hand and lead me to

The things that make me more like

You.

Show me a deed, lead me apart

To bring happiness to some sad heart,

Fill my odd hours with all that’s true

Pleasure and labor – the whole day

through.

Thus may my day be pure and

Bright;

Teach me to know the wrong from

right

And when shadows fall, I want to

Say

That I have lived a perfect day.

I wrote this tribute to Toni, capturing not only my sense of loss, but also the focus of our family values on inter-generational investment in public service.

We Are One…Continuum: a river nourishing the world

...I looked into the soul of my future today

And of my past

What’s in a name?

The power to shape

Mold, sculpt

Subliminally

Conscientiously

But not entirely

Consciously

Communication of a dream

Born not long after

The birth of the dreamer

I looked into the spirit of my future today

And of my past

A bright courageous future

Spanning many years

Of personal satisfaction

Human interaction

Scientific recognition

And public reaction

A future

That she

And they

Fostered

And foreshadowed.

Only she won’t be there.

And she’s the only one left.

Toni (Antronette) Yancey, MD, MPH is Professor, Department of Health Services, and Co-Director, UCLA Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Equity in the School of Public Health, with research interests in chronic disease prevention and health promotion policy intervention. She serves on the Board of Directors, among others, of the Partnership for a Healthier America, supporting First Lady Obama's Let's Move campaign. Her second book, Instant Recess: Building a Fit Nation 10 Minutes at a Time, was released in November 2010.

References

Barr-Anderson, D.J., M. AuYoung, M.C. Whitt-Glover, B.A. Glenn, A.K. Yancey (2011 January) Integration of short bouts of physical activity into organizational routine a systematic review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 40(1):76-93.

Gioia, D. (2002). Can Poetry Matter? St. Paul, MN: Graywolf Press.

Hillier, A., B. Cole, T.E. Smith, A.K. Yancey, J.D. Williams, S. Grier, & W.J. McCarthy. (2009 December). Clustering of outdoor advertisements for unhealthy products around child-serving institutions: A comparison of 3 cities. Health & Place. 15(4):935-45.

Kanaley, R. (1992) Mall Bone Marrow Drive Looks to Minorities African Americans Have Received Only 20 of 1,400 Transplants Since 1987. Philadelphia Inquirer Dec 20: B10

Maxwell, A.E., A.K. Yancey, M. AuYoung, J.J. Guinyard, W.J. McCarthy, & R. Bastani. (2011 September). Dissemination of organizational wellness practice and policy change: A mid-point evaluation of the L.A. basin REACH US Center of Excellence in Eliminating Disparities. Prev Chronic Dis. 8(5):A115.

Mistry, R., W. McCarthy, A. Yancey, Y. Lu, M. Patel. (2009 March). Adolescent resilience and patterns of health risk behaviors in California. Prev Med. 48(3):291-7.

UCLA Center to Eliminate Health Disparities and Samuels & Assoc. (2007 January). Failing Fitness: Physical Activity and Physical Education in Schools. A policy brief from The California Endowment.

Whitt-Glover, M., S.A. Ham, A. Yancey. (2011). Instant Recess®: A practical tool for increasing physical activity during the school day. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 5(3):289-97.

Yancey, A.K., W.J. McCarthy, G.G. Harrison, W.K. Wong, J.M. Siegel, J Leslie. (2006 May). Challenges in improving fitness: results of a community-based, randomized, controlled lifestyle change intervention. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 15(4):412-29.

Yancey, T. (2010) Instant Recess: Building a Fit Nation -- 10 Minutes at a Time. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Yancey, A., B. Cole, R. Brown, A. Hillier, J. Williams et al. (2009). A cross-sectional prevalence study of ethnically-targeted and general audience obesity-related advertising. Milbank Quarterly. 87:155-84.

Yancey, A.K., D. Grant, S. Witt, N. Kravitz-Wirtz, & R. Mistry. (2011). Role modeling, risk and resilience in adolescents: Evidence from the CHIS. J Adol Health. 48:36-43.

Yancey, A.K. & S.K. Kumanyika. (2007). Bridging the gap: Understanding the structure of social inequities in childhood obesity. Am J Prev Med. 33(4S):S172-74.

Yancey, A., J. Siegel, & K. McDaniel. (2002). Ethnic identity, role models, risk & health behaviors in urban adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adol Med. 156:55-61.

The challenges mentioned above provided the team with an unexpected opportunity to bring an intergenerational component to the project that had not been planned at the beginning. Undergraduate students and graduate interns from the Southeast Asian communities were able join the project, serving as on-set assistants, ad hoc interpreters, and video editors. This type of intergenerational collaboration was enriching for both the young people and the elders alike.

The challenges mentioned above provided the team with an unexpected opportunity to bring an intergenerational component to the project that had not been planned at the beginning. Undergraduate students and graduate interns from the Southeast Asian communities were able join the project, serving as on-set assistants, ad hoc interpreters, and video editors. This type of intergenerational collaboration was enriching for both the young people and the elders alike.

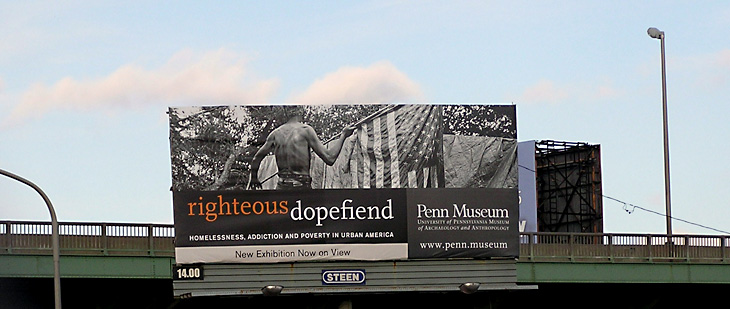

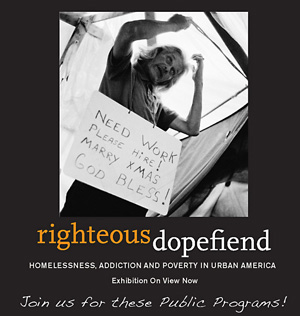

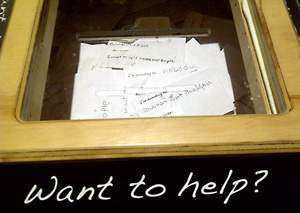

The museum extended the exhibit for an extra year and a half (running from December 2009 to March 2012), and most interesting to us was the way community groups, homeless and addiction services organizations and educators used the space, bringing their clients/patients/inmates/students for visits and reflection sessions. A blackboard and a comment and donation box allowed visitors to leave their input. Perhaps the most moving comments we have received have been from the family members of deceased heroin injectors and crack smokers. There are few public, safe, respectful, serious and forgiving spaces that acknowledge the unresolved anger, quiet confusion and frustrated longing left among close kin by addicted loved ones who have died (Garcia 2011). Most family members are forced to mourn their lost siblings, children or parents in silence—if not shame—and they remain an invisible community. The exhibit seems to allow them to come forward and situate in history and in public policy their family’s solitary painful experience in a larger shared community.

The museum extended the exhibit for an extra year and a half (running from December 2009 to March 2012), and most interesting to us was the way community groups, homeless and addiction services organizations and educators used the space, bringing their clients/patients/inmates/students for visits and reflection sessions. A blackboard and a comment and donation box allowed visitors to leave their input. Perhaps the most moving comments we have received have been from the family members of deceased heroin injectors and crack smokers. There are few public, safe, respectful, serious and forgiving spaces that acknowledge the unresolved anger, quiet confusion and frustrated longing left among close kin by addicted loved ones who have died (Garcia 2011). Most family members are forced to mourn their lost siblings, children or parents in silence—if not shame—and they remain an invisible community. The exhibit seems to allow them to come forward and situate in history and in public policy their family’s solitary painful experience in a larger shared community.  The more avant-garde exhibition space at the Slought Foundation of our initially simultaneous multimedia installation, “Righteous Dopefiend: Voices of the Homeless” ran for less than a month and it reached fewer viewers, primarily the web-based hipster public. More importantly, however, it introduced us to the value and untapped potential of multi-media—especially audio—installations of ethnographic material. For the exhibit, we prepared audio loops of excerpts from our hundreds of hours of recordings and combined them with photos of the daily activities of the characters speaking on the recording. This foray into audio-editing paired with photographs made us realize how much more the sound of voices communicates about racialized ethnicity, class, sex-and-gender, ethnographic rapport, suffering and human emotion than do transcriptions of these same voices frozen into print. Furthermore, the pain, anger, affectation, frustration, hopelessness or thoughtfulness of a tone of voice and turn of phrase are rendered more memorable or poignant by the photos-in-action displayed simultaneously with the audio loop. The limits of agency become evident to audiences listening to conversations-in-actions among the homeless. Stutters, pauses, self-corrections, hyperbole and emotional tones reveal personal ambivalences and bring alive the intimate structural and interpersonal quandaries and inconsistencies that condemn dreams and good intentions to failure—including, in the case of street addicts: safe injection practices, sobriety and consistent relations of social solidarity.

The more avant-garde exhibition space at the Slought Foundation of our initially simultaneous multimedia installation, “Righteous Dopefiend: Voices of the Homeless” ran for less than a month and it reached fewer viewers, primarily the web-based hipster public. More importantly, however, it introduced us to the value and untapped potential of multi-media—especially audio—installations of ethnographic material. For the exhibit, we prepared audio loops of excerpts from our hundreds of hours of recordings and combined them with photos of the daily activities of the characters speaking on the recording. This foray into audio-editing paired with photographs made us realize how much more the sound of voices communicates about racialized ethnicity, class, sex-and-gender, ethnographic rapport, suffering and human emotion than do transcriptions of these same voices frozen into print. Furthermore, the pain, anger, affectation, frustration, hopelessness or thoughtfulness of a tone of voice and turn of phrase are rendered more memorable or poignant by the photos-in-action displayed simultaneously with the audio loop. The limits of agency become evident to audiences listening to conversations-in-actions among the homeless. Stutters, pauses, self-corrections, hyperbole and emotional tones reveal personal ambivalences and bring alive the intimate structural and interpersonal quandaries and inconsistencies that condemn dreams and good intentions to failure—including, in the case of street addicts: safe injection practices, sobriety and consistent relations of social solidarity.