Photo Credit: © chombosan / fotolia

Communities throughout the United States are facing unprecedented infrastructure challenges including compromised energy, water, and transportation systems. Unless addressed, decades of neglect and lack of investment will result in loss of business sales, reduced jobs and wages, and negative impacts to the country’s GDP.1 Federal, state, and local governments face a $1.4 trillion public funding gap to address infrastructure challenges -- and by 2040, this funding gap will be more than $5 trillion.2 Unlocking Private Capital to Finance Sustainable Infrastructure, a new report produced by Meister Consultants Group, Inc. for Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), presents a first-of-its kind Investment Design Framework that will help state and local governments catalyze private investment in sustainable infrastructure and fill these critical funding gaps.

The term “sustainable infrastructure” describes infrastructure that is built and managed to meet economic, environmental, and social goals.3 It can be applied to a wide variety of infrastructure sub-sectors including energy, transportation, waste, water, and stormwater management. Green infrastructure and natural infrastructure are types of sustainable infrastructure that use vegetation or other natural elements to provide critical services and meet infrastructure needs while providing a myriad of environmental and social co-benefits. These co-benefits have real monetary value, help create more cost-effective infrastructure solutions and enable governments to achieve multiple goals with limited resources.

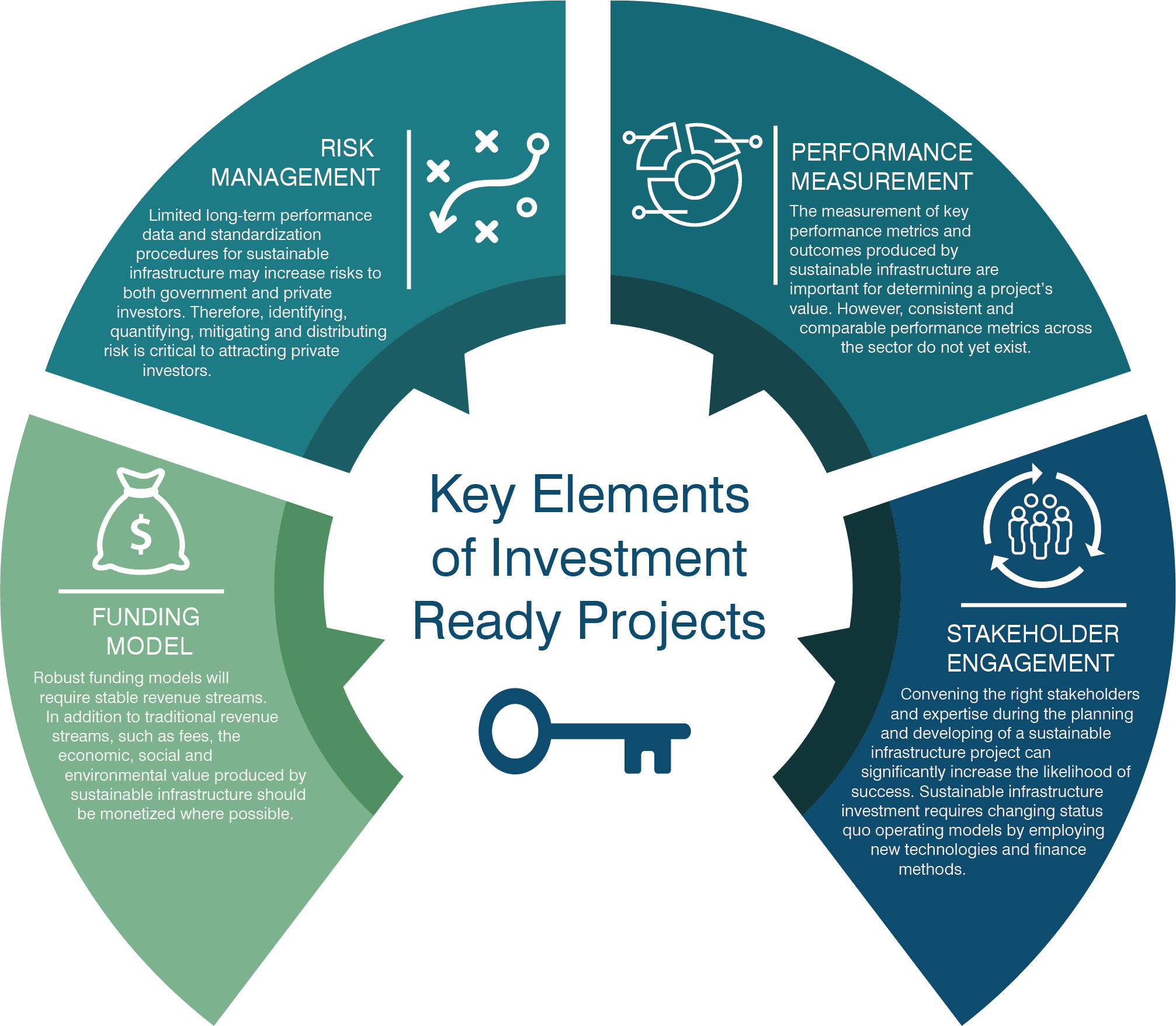

The measurement and monetization of environmental and social co-benefits bolsters the economic rationale for investments in sustainable infrastructure, attracts a wider pool of potential investors, and underpins the four elements of the Investment Design Framework:

Environmental impact bonds (EIB) address the core components of the Investment Design Framework and have emerged as an innovative financing mechanism that can increase the flow of private capital to sustainable infrastructure projects. Like the social impact bonds (SIBs) that preceded them, EIBs apply pay-for-success (PFS) financing to measure, monetize, and deliver positive environmental and social outcomes. EIBs can be used to pilot a new approach whose performance is viewed as uncertain or to scale-up a solution that has been tested on a small scale. Private investors participating in a PFS model provide the upfront capital needed for deploying these innovative solutions. Following deployment and program evaluation, the “payor,” the public agency or private institution that benefits from these solutions, makes payments to investors contingent on the achievement of agreed-upon outcomes of the program.

EIBs can be issued as true municipal bonds, either as general obligation or as revenue bonds, under the bonding authority of the issuing body. They can also be structured as a performance contract or loan that would not count against the debt capacity of the issuing body. EIBs can also be backed or “guaranteed” by a philanthropic organization that agrees to make part of the repayment to investors in the event that an intervention does not achieve its intended results. The involvement of such a philanthropic “backstop” can help provide assurance to investors in projects or interventions whose outcomes are viewed as riskier. By distributing risk across a suite of capital providers, EIBs can be effective tools for leveraging public and philanthropic capital to mobilize private investment.

The DC Water and Sewer Authority (DC Water) pioneered the environmental impact bond approach in 2016 with a $25 million issuance to finance deployment of green infrastructure projects (e.g., permeable pavement and bioretention) on 20 acres of parkland in Washington, D.C. Because the performance of green infrastructure was viewed as uncertain, DC Water chose this approach to observe the outcomes of the projects before deploying their broader 360+ acre green infrastructure investment strategy. The EIB was issued as a private placement bond with Goldman Sachs and Calvert Foundation as the investors. The EIB includes performance tiers that tie outcomes to the payments that these investors receive: if the green infrastructure significantly underperforms, the investors will receive an interest rate close to zero, and if the green infrastructure performs significantly above expectations, they receive a higher interest rate.4 Other communities are beginning to look at EIBs and PFS as a model for financing a variety of sustainable infrastructure projects. Eight states, Washington D.C., and several local governments have already enacted enabling legislation, while many more jurisdictions are considering similar policies.5

In June 2017, Louisiana passed legislation that authorizes the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) to use PFS. With support from NatureVest’s new Conservation Investment Accelerator Program, the conservation investing unit of The Nature Conservancy, EDF is working with CPRA and Quantified Ventures to develop the nation’s first coastal resiliency-focused EIB. The Louisiana Coastal Wetland Restoration and Resilience Environmental Impact Bond aims to bring public, private, and non-profit resources together to accelerate Louisiana’s coastal restoration and resiliency plans.

Massachusetts is well positioned to explore the use of EIBs and PFS to support innovative sustainable infrastructure solutions. The state was a pioneer of PFS and social impact bonds, having passed the first PFS-enabling legislation in 2012. The law’s broad scope does not specify specific sectors or structures, allowing PFS to be used for a wide range of activities.6

EIBs can be a valuable tool to support Climate Ready Boston, the city’s ongoing initiative to help Boston plan for the future impacts of climate change.7 The city’s new report, Coastal Resilience Solutions for East Boston and Charlestown, identifies a wide variety of open space strategies that will help mitigate the risks of coastal flooding and sea level rise. Strategies like the development of elevated waterfront parks and plazas, or the creation of nature-based features like marshes, living shorelines, wetland terraces, etc., could be piloted with environmental impact bonds, allowing the city to evaluate the strategies’ efficacy before making commitments at a larger scale.

Unlocking the scale of private capital needed to satisfy current and future infrastructure demands requires active partnership and collaboration between the public and private sectors, as well as support from non-profits and the philanthropic community. Sustainable infrastructure can help to right-size demand by providing economic, environmental, and social benefits in a comprehensive, cost-effective manner. Environmental impact bonds represent a multi-sectoral financing mechanism to support innovative infrastructure solutions. Sustainable infrastructure that grows the economy, supports local jobs, supports social equity, reduces pollution, and protects communities from the impacts of climate change is critical to the continued vitality of the United States. With the public and private sector working together and investing in critical sustainable infrastructure, the U.S. can once again become a leader in infrastructure and create a more livable future for all.

Author Bios

Namrita Kapur

Namrita Kapur, Managing Director - EDF+Business, leads EDF’s Sustainable Finance Team. With expertise in developing corporate partnerships that accelerate corporate innovation, she works on clearing barriers so as to attract private capital to support ecosystem resiliency, as well as sustainably managed fisheries, endangered species habitat, zero deforestation, and energy efficiency. Namrita has designed and executed initiatives for leveraging capital markets in the United States and abroad. Prior to joining EDF, Namrita played an integral role in establishing the strategy and developing the infrastructure of Root Capital, a social investment fund pioneering finance in rural communities in the developing world. Namrita has an M.B.A. from the Yale School of Management, an M.A. in Environmental Management, Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, and currently serves on the Finance Committee for the Board of the Environmental League of Massachusetts and on the Advisory Board of the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board.

Dakota Gangi

Dakota develops and integrates sustainable finance strategies across EDF’s core program areas (Climate & Energy, Oceans, Ecosystems, and Health). Drawing from his background in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance analysis, sustainability management, and stakeholder engagement, he has designed tools for investors to improve their capacity to engage with companies on environmental performance. He works directly with EDF project managers to identify opportunities for leveraging the private capital markets to accelerate progress against EDF’s Blueprint 2020 goals. Prior to joining EDF, and as a member of CDP’s Investor Initiative team (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project), Dakota worked with North American investors to improve their capacity to integrate ESG data into the investment decision-making process. Dakota has a MSc. in Sustainability Management from Columbia University and a B.A. in Environmental Studies from Binghamton University (SUNY). He is also a 2018 Level III candidate in the CFA program and a Fundamentals of Sustainable Accounting (FSA) Credential Level II candidate.

Footnotes

1 American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), Failure to Act: Closing the Infrastructure Investment Gap for America’s Economic Future, 4, Link.

2 ASCE, Failure to Act, 14.

3 New Climate Economy, The Sustainable Infrastructure Imperative: Financing for Better Growth and Development, Link.

4 “Environmental Impact Bond,” DC Water, Quantified Ventures, accessed October 25, 2017, Link

5 Perry Teicher, John Grossman, and Marcia Chong, Authorizing Pay for Success Projects: A Legislative Review and Model Pay for Success Legislation, (San Francisco: Third Sector Capital Partners, 2016), 5, Link.

6 Ibid.

7 "Climate Ready Boston," Boston.gov, Link.